Editor’s note: The following is extracted from David: Five Sermons, by Charles Kingsley (published 1865).

2 Samuel i. 26. I am distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan: very pleasant hast thou been unto me: thy love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women.

Passing the love of woman! That is a hard saying. What love can pass that? Yet David doubtless spoke truth. He was a man who must have had reason enough to know what woman’s love was like; and when he said that the love of Jonathan for him passed even that, he bestowed on his friend praise which will be immortal.

The name of Jonathan will remain for ever as the perfect pattern of friendship.

Let us think a little today over his noble character and his tragical history. It will surely do us good. If it does nothing but make us somewhat ashamed of ourselves, that is almost the best thing which can happen to us or to any man.

We first hear of Jonathan as doing a very gallant deed. We might expect as much. It is only great-hearted men who can be true friends; mean and cowardly men can never know what friendship means.

The Israelites were hidden in thickets, and caves, and pits, for fear of the Philistines, when Jonathan was suddenly inspired to attack a Philistine garrison, under circumstances seemingly desperate. ‘And that first slaughter, which Jonathan and his armour-bearer made, was about twenty men, within, as it were, an half-acre of land, which a yoke of oxen might plough.’

That is one of those little hints which shews that the story is true, written by a man who knew the place—who had probably been in the great battle of Beth-aven, which followed, and had perhaps ascended the rock where Jonathan had done his valiant deed, and had seen the dead bodies lying as they had fallen before him and his armour-bearer.

Then follows the story of David’s killing Goliath, and coming back to Saul with the giant’s head in his hand, and answering modestly to him, ‘I am the son of thy servant Jesse the Bethlehemite.’

‘And it came to pass, when he had made an end of speaking unto Saul, that the soul of Jonathan was knit with the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul.

‘Then Jonathan and David made a covenant, because he loved him as his own soul.

‘And Jonathan stripped himself of the robe that was upon him, and gave it to David, and his garments, even to his sword, and to his bow, and to his girdle.’

He loved him as his own soul. And why? Because his soul was like the soul of David; because he was modest, he loved David’s modesty; because he was brave, he loved David’s courage; because he was virtuous, he loved David’s virtue. He saw that David was all that he was himself, and more; and therefore he loved him as his own soul. And therefore I said, that it is only noble and great hearts who can have great friendships; who admire and delight in other men’s goodness; who, when they see a great and godlike man, conceive, like Jonathan, such an affection for him that they forget themselves, and think only of him, till they will do anything for him, sacrifice anything for him, as Jonathan did for David.

For remember, that Jonathan had cause to hate and envy David rather than love him; and that he would have hated him if there had been any touch of meanness or selfishness in his heart. Gradually he learnt, as all Israel learnt, that Samuel had anointed David to be king, and that he, Jonathan, was in danger of not succeeding after Saul’s death. David stood between him and the kingdom. And yet he did not envy David—did not join his father for a moment in plotting his ruin. He would oppose his father, secretly indeed, and respectfully; but still, he would be true to David, though he had to bear insults and threats of death.

And mark here one element in Jonathan’s great friendship. Jonathan is a pious man, as well as a righteous one. He believes the Lord’s messages that he has chosen David to be king, and he submits; seeing that it is just and right, and that David is worthy of the honour, though it be to the hurt of himself and of his children after him. It is the Lord’s will; and he, instead of repining against it, must carry it out as far as he is concerned. Yes; those who are most true to their fellow-men are always those who are true to God; for the same spirit of God which makes them fear God makes them also love their neighbour.

When David escapes from Saul to Samuel, it is Jonathan who does all he can to save him. The two friends meet secretly in the field.

‘And Jonathan said unto David, O Lord God of Israel, when I have sounded my father about to-morrow any time, or the third day, and, behold, if there be good toward David, and I then send not unto thee, and shew it thee; the Lord do so and much more to Jonathan.’

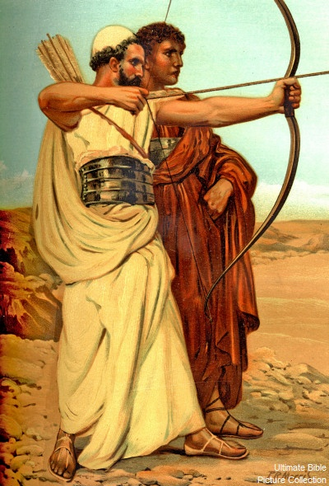

Then David and Jonathan agree upon a sign between them, by which David may know Saul’s humour without his bow-bearer finding out David. He will shoot three arrows toward the place where David is in hiding; and if he says to his bow-bearer, The arrows are on this side of thee, David is to come; for he is safe. But if he says, The arrows are beyond thee, David must flee for his life, for the Lord has sent him away.

Then Jonathan goes in to meat with his father Saul, and excuses David for being absent.

‘Then Saul’s anger was kindled against Jonathan, and he said unto him, Thou son of the perverse, rebellious woman, do not I know that thou hast chosen the son of Jesse to thine own confusion, and unto the confusion of thy mother? For as long as the son of Jesse liveth upon the ground, thou shalt not be established, nor thy kingdom. Wherefore now send and fetch him unto me, for he shall surely die. And Jonathan answered Saul his father, and said unto him, Wherefore shall he be slain? what hath he done? And Saul cast a javelin at him to smite him; whereby Jonathan knew that it was determined of his father to slay David.’

He goes to the field and shoots the arrows, and gives the sign agreed on. He sends his bow-bearer back to the city, and David comes out of his hiding-place in the rock Ezel.

‘And as soon as the lad was gone, David arose out of a place toward the south, and fell on his face to the ground, and bowed himself three times; and they kissed one another, and wept one with another, until David exceeded. And Jonathan said to David, Go in peace, forasmuch as we have sworn both of us in the name of the Lord, saying, The Lord be between me and thee, and between my seed and thy seed for ever. And he arose and departed: and Jonathan went into the city.’

And so the two friends parted, and saw one another, it seems, but once again, when Jonathan went to David in the forest of Ziph, and ‘strengthened his hand in God,’ with noble words.

After that, Jonathan vanishes from the story of David. We hear only of him that he died fighting by his father’s side, upon the downs of Gilboa. The green plot at their top, where the Israelites’ last struggle was probably made, can be seen to this day; and there most likely Jonathan fell, and over him David raised his famous lamentation:

‘O Jonathan, thou wast slain in thine high places. I am distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan: very pleasant hast thou been unto me: thy love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women. How are the mighty fallen, and the weapons of war perished!’

So ends the beautiful and tragical story of a truly gallant man. Seldom, indeed, will there be seen in the world such perfect friendship between man and man, as that between Jonathan and David. Seldom, indeed, shall we see anyone loving and adoring the very man whom his selfish interest would teach him to hate and to supplant. But still every man may have, and ought to have a friend. Wretched indeed, and probably deservedly wretched, is the man who has none. And every man may learn from this story of Jonathan how to choose his friends.

I say, to choose. No one is bound to be at the mercy of anybody and everybody with whom he may come in contact. No one is bound to say, That man lives next door to me, therefore he must be my friend. We are bound not to avoid our neighbours. They are put near us by God in his providence. God intends every one of them, good or bad, to help in educating us, in giving us experience of life and manners. We are to learn from them, live with them in peace and charity, and only avoid them when we find that their company is really doing us harm, and leading us into sin and folly. But a friend—which is a much deeper and more sacred word than neighbour—a friend we have the right and the power to choose; and our wisest plan will be to copy Jonathan, and choose our friends, not for their usefulness, but for their goodness; not for their worth to us, but for their worth in themselves; and to choose, if possible, people superior to ourselves. If we meet a man better than ourselves, more wise than ourselves, more learned, more experienced, more delicate-minded, more high-minded, let us take pains to win his esteem, to gain his confidence, and to win him as a friend, for the sake of his worth.

Then in our friendship, as in everything else in the world, we shall find the great law come true, that he that loseth his life shall save it. He who does not think of himself and his own interest will be the very man who will really help himself, and further his own interest the most. For the friend whom we have chosen for his own worth, will be the one who will be worth most to us. The friend whom we have loved and admired for his own sake, will be the one who will do most to raise our character, to teach us, to refine us, to help us in time of doubt and trouble. The higher-minded man our friend is, the higher-minded will he make us. For it is written, ‘As iron sharpeneth iron, so a man sharpeneth the face of his friend.’

Nothing can be more foolish, or more lowering to our own character, than to choose our friends among those who can only flatter us, and run after us, who look up to us as oracles, and fetch and carry at our bidding, while they do our souls and characters no good, but merely feed our self-conceit, and lower us down to their own level. But it is wise, and ennobling to our own character, to choose our friends among those who are nearer to God than we are, more experienced in life, and more strong and settled in character. Wise it is to have a friend of whom we are at first somewhat afraid; before whom we dare not say or do a foolish thing, whose just anger or contempt would be to us a thing terrible. Better it is that friendship should begin with a little wholesome fear, till time and mutual experience of each other’s characters shall have brought about the perfect love which casts out fear. Better to say with David, ‘He that telleth lies shall not stay in my sight; I will not know a wicked person. Yea, let the righteous rather smite me friendly and reprove me. All my delight is in the saints that are in the earth, and in such as excel in virtue.’

And let no man fancy that by so doing he lowers himself, and puts himself in a mean place. There is no man so strong-minded but what he may find a stronger-minded man than himself to give him counsel; no man is so noble-hearted but what he may find a nobler-hearted man than himself to keep him up to what is true and just and honourable, when he is tempted to play the coward, and be false to God’s Spirit within him. No man is so pure-minded but what he may find a purer-minded person than himself to help him in the battle against the world, the flesh, and the devil.

My friends, do not think it a mean thing to look up to those who are superior to yourselves. On the contrary, you will find in practice that it is only the meanest hearts, the shallowest and the basest, who feel no admiration, but only envy for those who are better than themselves; who delight in finding fault with them, and blackening their character, and showing that they are not, after all, so much superior to other people; while it is the noblest-hearted, the very men who are most worthy to be admired themselves, who, like Jonathan, feel most the pleasure, the joy, and the strength of reverence; of having some one whom they can look up to and admire; some one in whose company they can forget themselves, their own interest, their own pleasure, their own honour and glory, and cry, Him I must hear; him I must follow; to him I must cling, whatever may betide. Blessed and ennobling is the feeling which gathers round a wise teacher or a great statesman all the most earnest, high-minded, and pious youths of his generation; the feeling which makes soldiers follow the general whom they trust, they know not why or whither, through danger, and hunger, and fatigue, and death itself; the feeling which, in its highest perfection, made the Apostles forsake all and follow Christ, saying, ‘Lord, to whom shall we go? Thou hast the words of eternal life’—which made them ready to work and to die for him whom the world called the son of the carpenter, but whom they, through the Spirit of God bearing witness with their own pure and noble spirits, knew to be the Son of the Living God.

Aye, a blessed thing it is for any man or woman to have a friend; one human soul whom we can trust utterly; who knows the best and the worst of us, and who loves us, in spite of all our faults; who will speak the honest truth to us, while the world flatters us to our face, and laughs at us behind our back; who will give us counsel and reproof in the day of prosperity and self-conceit; but who, again, will comfort and encourage us in the day of difficulty and sorrow, when the world leaves us alone to fight our own battle as we can.

If we have had the good fortune to win such a friend, let us do anything rather than lose him. We must give and forgive; live and let live. If our friend have faults, we must bear with them. We must hope all things, believe all things, endure all things, rather than lose that most precious of all earthly possessions—a trusty friend.

And a friend, once won, need never be lost, if we will only be trusty and true ourselves. Friends may part—not merely in body, but in spirit, for a while. In the bustle of business and the accidents of life they may lose sight of each other for years; and more—they may begin to differ in their success in life, in their opinions, in their habits, and there may be, for a time, coldness and estrangement between them; but not for ever, if each will be but trusty and true.

For then, according to the beautiful figure of the poet, they will be like two ships who set sail at morning from the same port, and ere nightfall lose sight of each other, and go each on its own course, and at its own pace, for many days, through many storms and seas; and yet meet again, and find themselves lying side by side in the same haven, when their long voyage is past.

And if not, my friends; if they never meet; if one shall founder and sink upon the seas, or even change his course, and fly shamefully home again: still, is there not a Friend of friends who cannot change, but is the same yesterday, to-day, and for ever?

What says the noble hymn:—

‘When gathering clouds around I view,

And days are dark and friends are few,

On him I lean, who, not in vain,

Experienced every human pain:

He sees my griefs, allays my fears,

And counts and treasures up my tears.’

Passing the love of woman was his love, indeed; and of him Jonathan was but such a type, as the light in the dewdrop is the type of the sun in heaven.

He himself said—and what he said, that he fulfilled—‘Greater love hath no man than this—that a man lay down his life for his friends.’

In treachery and desertion; in widowhood and childlessness; in the hour of death, and in the day of judgment, when each soul must stand alone before its God, one Friend remains, and that the best of all.