Editor’s note: The following is extracted from David: Five Sermons, by Charles Kingsley (published 1865).

Psalm xxvii. 1. The Lord is my light, and my salvation; whom then shall I fear? The Lord is the strength of my life; of whom then shall I be afraid?

I said, last Sunday, that the key-note of David’s character was not the assertion of his own strength, but the confession of his own weakness. And I say it again.

But it is plain that David had strength, and of no common order; that he was an eminently powerful, able, and successful man. From whence then came that strength? He says, from God. He says, throughout his life, as emphatically as did St. Paul after him, that God’s strength was made perfect in his weakness.

God is his deliverer, his guide, his teacher, his inspirer. The Lord is his strength, who teaches his hands to war, and his fingers to fight; his hope and his fortress, his castle and deliverer, his defence, in whom he trusts; who subdueth the people that is under him.

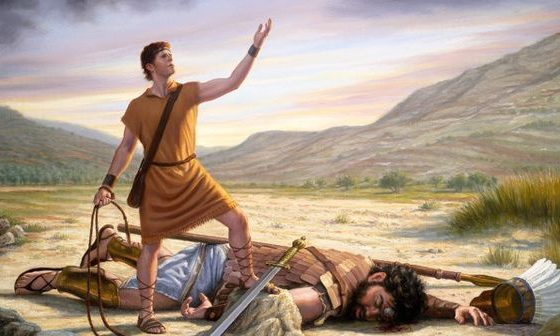

To God he ascribes, not only his success in life, but his physical prowess. By God’s help he slays the lion and the bear. By God’s help he has nerve to kill the Philistine giant. By God’s help he is so strong that his arms can break even a bow of steel. It is God who makes his feet like hart’s feet, and enables him to leap over the walls of the mountain fortresses.

And we must pause ere we call such utterances mere Eastern metaphor. It is far more probable that they were meant as and were literal truths. David was not likely to have been a man of brute gigantic strength. So delicate a brain was probably coupled to a delicate body. Such a nature, at the same time, would be the very one most capable, under the influence—call it boldly, inspiration—of a great and patriotic cause, of great dangers and great purposes; capable, I say, at moments, of accesses of almost superhuman energy, which he ascribed, and most rightly, to the inspiration of God.

But it is not merely as his physical inspirer or protector that he has faith in God. He has a deeper, a far deeper instinct than even that; the instinct of a communion, personal, practical, living, between God, the fount of light and goodness, and his own soul, with its capacity of darkness as well as light, of evil as well as good.

In one word, David is a man of faith and a man of prayer—as God grant all you may be. It is this one fixed idea, that God could hear him, and that God would help him, which gives unity and coherence to the wonderful variety of David’s Psalms. It is this faith which gives calm confidence to his views of nature and of man; and enables him to say, as he looks upon his sheep feeding round him, ‘The Lord is my Shepherd, therefore I shall not want.’ Faith it is which enables him to foresee that though the heathen rage, and the kings of the earth stand up, and the rulers take counsel together against the Lord and his Anointed, yet the righteous cause will surely prevail, for God is king himself. Faith it is which enables him to bear up against the general immorality, and while he cries, ‘Help me, Lord, for there is not one godly man left, for the faithful fail from among the children of men’—to make answer to himself in words of noble hope and consolation, ‘Now for the comfortless troubles’ sake of the needy, and because of the deep sighing of the poor, I will up, saith the Lord, and will help every one from him that swelleth against him, and will set him at rest.’

Faith it is which gives a character, which no other like utterances have, to those cries of agony—cries as of a lost child—which he utters at times with such noble and truthful simplicity. They issue, almost every one of them, in a sudden counter-cry of joy as pathetic as the sorrow which has gone before. ‘O Lord, rebuke me not in thine indignation: neither chasten me in thy displeasure. Have mercy upon me, O Lord, for I am weak: O Lord, heal me, for my bones are vexed. My soul also is sore troubled: but, Lord, how long wilt thou punish me? Turn thee, O Lord, and deliver my soul: O save me for thy mercy’s sake. For in death no man remembereth thee: and who will give thee thanks in the pit? I am weary of my groaning; every night wash I my bed: and water my couch with my tears. My beauty is gone for very trouble: and worn away because of all mine enemies. Away from me, all ye that work vanity, for the Lord hath heard the voice of my weeping. The Lord hath heard my petition: the Lord will receive my prayer.’

Faith it is, in like wise, which gives its peculiar grandeur to that wonderful 18th Psalm, David’s song of triumph; his masterpiece, and it may be the masterpiece of human poetry, inspired or uninspired, only approached by the companion-Psalm, the 144th. From whence comes that cumulative energy, by which it rushes on, even in our translation, with a force and swiftness which are indeed divine; thought following thought, image image, verse verse, before the breath of the Spirit of God, as wave leaps after wave before the gale? What is the element in that ode, which even now makes it stir the heart like a trumpet? Surely that which it itself declares in the very first verse:

‘I will love thee, O Lord, my strength; the Lord is my stony rock, and my defence: my Saviour, my God, and my might, in whom I will trust, my buckler, the horn also of my salvation, and my refuge.’

What is it which gives life and reality to the magnificent imagery of the seventh and following verses? ‘The earth trembled and quaked: the very foundations also of the hills shook, and were removed, because he was wroth. There went a smoke out in his presence: and a consuming fire out of his mouth, so that coals were kindled at it. He bowed the heavens also, and came down: and it was dark under his feet. He rode upon the cherubims, and did fly: he came flying upon the wings of the wind. He made darkness his secret place: his pavilion round about him with dark water, and thick clouds to cover him. At the brightness of his presence his clouds removed: hailstones, and coals of fire. The Lord also thundered out of heaven, and the Highest gave his thunder: hailstones, and coals of fire. He sent out his arrows, and scattered them: he cast forth lightnings, and destroyed them. The springs of waters were seen, and the foundations of the round world were discovered, at thy chiding, O Lord: at the blasting of the breath of thy displeasure. He shall send down from on high to fetch me: and shall take me out of many waters.’ What protects such words from the imputation of mere Eastern exaggeration? The firm conviction that God is the deliverer, not only of David, but of all who trust in God; that the whole majesty of God, and all the powers of nature, are arrayed on the side of the good and of the oppressed. ‘The Lord shall reward me after my righteous dealing: according to the cleanness of my hands shall he recompense me. Because I have kept the ways of the Lord: and have not forsaken my God, as the wicked doth. For I have an eye unto all his laws: and will not cast out his commandments from me. I was also uncorrupt before him: and eschewed mine own wickedness. Therefore shall the Lord reward me after my righteous dealing: and according unto the cleanness of my hands in his eyesight. With the holy thou shalt be holy: and with a perfect man thou shalt be perfect.’

Faith, again, it is, to turn from David’s highest to his lowest phase—faith in God it is which has made that 51st Psalm the model of all true penitence for evermore. Faith in God, in the spite of his full consciousness that God is about to punish him bitterly for the rest of his life. Faith it is which gives to that Psalm its peculiarly simple, deliberate, manly tone; free from all exaggerated self-accusations, all cowardly cries of terror. He is crushed down, it is true. The tone of his words shews us that throughout. But crushed by what? By the discovery that he has offended God? Not in the least. For the sake of your own souls, as well as for that of honest critical understanding of the Scriptures, do not foist that meaning into David’s words. He never says that he had offended God. Had he been a mediæval monk, had he been an average superstitious man of any creed or time, he would have said so, and cried, I have offended God; he is offended and angry with me, how shall I avert his wrath?

Not so. David has discovered not an angry, but a forgiving God; a God of love and goodness, who desires to make his creatures good. Penitential prayers in all ages have too often wanted faith in God, and therefore have been too often prayers to avert punishment. This, this—the model of all truly penitent prayers—is that of a man who is to be punished, and is content to take his punishment, knowing that he deserves it, and far more beside. And why? Because, as always, David has faith in God. God is a good and just being, and he trusts him accordingly; and that very discovery of the goodness, not the sternness of God, is the bitterest pang, the deepest shame to David’s spirit. Therefore he can face without despair the discovery of a more deep, radical inbred evil in himself than he ever expected before. ‘Behold, I was shapen in wickedness: and in sin hath my mother conceived me;’ because he could say also, ‘Thou requirest truth in the inward parts; and shalt make me to understand wisdom secretly.’ He can cry to God, out of the depths of his foulness, ‘Make me a clean heart, O God: and renew a right spirit within me. Cast me not away from thy presence: and take not thy holy Spirit from me. O give me the comfort of thy help again: and stablish me with thy free Spirit. Then shall I teach thy ways unto the wicked: and sinners shall be converted unto thee.’ He can cry thus, because he has discovered that the will of God is not to hate, not to torture, not to cast away from his presence, but to restore his creatures to goodness, that he may thereby restore them to usefulness. David has discovered that God demands no sacrifice, much less self-torturing penance. What he demands is the heart. The sacrifice of God is a troubled spirit. A broken and a contrite heart he will not despise. It is such utterances as these which have given, for now many hundred years, their priceless value to the little book of Psalms ascribed to the shepherd outlaw of the Judæan hills. It is such utterances as these which have sent the sound of his name into all lands, and his words throughout all the world. Every form of human sorrow, doubt, struggle, error, sin; the nun agonising in the cloister; the settler struggling for his life in Transatlantic forests; the pauper shivering over the embers in his hovel, and waiting for kind death; the man of business striving to keep his honour pure amid the temptations of commerce; the prodigal son starving in the far country, and recollecting the words which he learnt long ago at his mother’s knee; the peasant boy trudging a-field in the chill dawn, and remembering that the Lord is his shepherd, therefore he will not want—all shapes of humanity have found, and will find to the end of time, a word said to their inmost hearts, and more, a word said for those hearts to the living God of heaven, by the vast humanity of David, the man after God’s own heart; the most thoroughly human figure, as it seems to me, which had appeared upon the earth before the coming of that perfect Son of man, who is over all, God blessed for ever. Amen.

It may be said, David’s belief is no more than the common belief of fanatics. They have in all ages fancied themselves under the special protection of Deity, the object of special communications from above.

Doubtless they have; and evil conclusions have they drawn therefrom, in every age. But the existence of a counterfeit is no argument against the existence of the reality; rather it is an argument for the existence of the reality. In this case it is impossible to conceive how the idea of communion with an unseen being ever entered the human mind at all, unless it had been put there originally by fact and experience. Man would never have even dreamed of a living God, had not that living God been a reality, who did not leave the creature to find his Creator, but stooped from heaven, at the very beginning of our race, to find his creature.

And a reality you will surely find it—that living and practical communication between your souls, and that Father in heaven who created them. It will not be real, but morbid, even imaginary, just in proportion as your souls are tainted with self-conceit, ambition, self-will, malice, passion, or any wilful vice; especially with the vice of bigotry, which settles beforehand for God what he shall teach the soul, and in what manner he shall teach it, and turns a deaf ear to his plainest lessons if they cannot be made to fit into some favourite formula or theory. But it will be real, practical, healthy, soul-saving, in the very deepest sense of that word, just in proportion as your eye is single and your heart pure; just in proportion as you hunger and thirst after righteousness, and wish and try simply and humbly to do your duty in that station to which God has called you, and to learn joyfully and trustingly anything and everything which God may see fit to teach you. Then as your day your strength shall be. Then will the Lord teach you, and inform you with his eye, and guide you in the way wherein you should go. Then will you obey that appeal of the Psalmist, ‘Be ye not like to horse and mule, which have no understanding, whose mouths must be held in with bit and bridle, lest they fall upon thee. Great plagues remain for the ungodly. But whoso putteth his trust in the Lord, mercy embraceth him on every side.’

For understand this well, young men, and settle it in your hearts as the first condition of human life, yea, of the life of every rational created being, that a man is justified only by faith; and not only a man, but angels, archangels, and all possible created spirits, past, present, and to come. All stand, all are in their right state, only as long as they are consciously dependent on God the Father of spirits and his Son Jesus Christ the Lord, in whom they live and move and have their being. The moment they attempt to assert themselves, whether their own power, their own genius, their own wisdom, or even their own virtue, they ipso facto sin, and are justified and just no longer; because they are trying to take themselves out of their just and right state of dependence, and to put themselves into an unjust and wrong state of independence. To assert that anything is their own, to assert that their virtue is their own, just as much as to assert that their wisdom, or any other part of their being, is their own, is to deny the primary fact of their existence—that in God they live and move and have that being. And therefore Milton’s Satan, though, over and above all his other grandeurs, he had been adorned with every virtue, would have been Satan still by the one sin of ingratitude, just because and just as long as he set up himself, apart from that God from whom alone comes every good and perfect gift.

Settle it in your hearts, young men, settle it in your hearts—or rather pray to God to settle it therein; and if you would love life and see good days, recollect daily and hourly that the only sane and safe human life is dependence on God himself, and that—

Unless above himself he can

Exalt himself, how poor a thing is man.