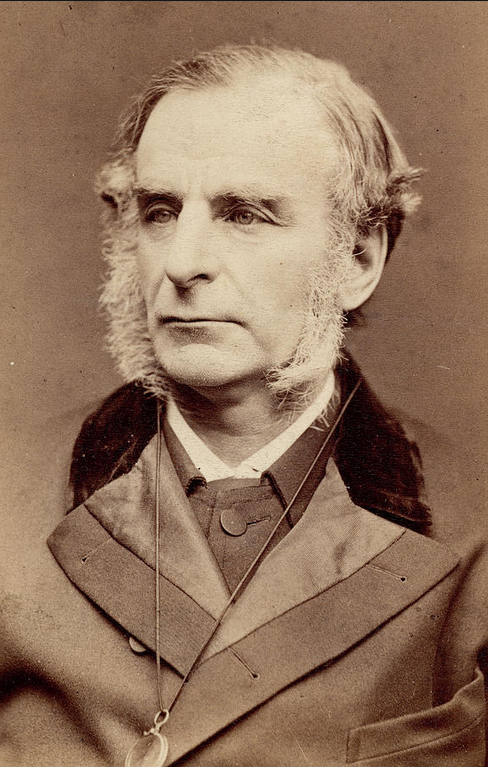

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from David: Five Sermons, by Charles Kingsley (published 1865).

Psalm cxliii. 11, 12. Quicken me, O Lord, for thy name’s sake: for thy righteousness’ sake bring my soul out of trouble. And of thy mercy cut off mine enemies, and destroy all them that afflict my soul: for I am thy servant.

There are those who would say that I dealt unfairly last Sunday by the Psalms of David; that in order to prove them inspired, I ignored an element in them which is plainly uninspired, wrong, and offensive; namely, the curses which he invokes upon his enemies. I ignored it, they would say, because it was fatal to my theory! because it proved David to have the vindictive passions of other Easterns; to be speaking, not by the inspiration of God, but of his own private likes and dislikes; to be at least a fanatic who thinks that his cause must needs be God’s cause, and who invokes the lightnings of heaven on all who dare to differ from him. Others would say that such words were excusable in David, living under the Old Law; for it was said by them of old time, ‘Thou shalt love thy neighbour and hate thine enemy:’ but that our Lord has formally abrogated that permission; ‘But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, and do good to those who despitefully use you and persecute you.’ How unnecessary, and how wrong then, they would say, it is of the Church of England to retain these cursing Psalms in her public worship, and put them into the mouths of her congregations. Either they are merely painful, as well as unnecessary to Christians; or if they mean anything, they excuse and foster the habit too common among religious controversialists of invoking the wrath of heaven on their opponents.

I argue with neither of the objectors. But the question is a curious and an important one; and I am bound, I think, to examine it in a sermon which, like the present, treats of David’s chivalry.

What David meant by these curses can be best known from his own actions. What certain persons have meant by them since is patent enough from their actions. Mediæval monks considered but too often the enemies of their creed, of their ecclesiastical organisation, even of their particular monastery, to be ipso facto enemies of God; and applied to them the seeming curses of David’s Psalms, with fearful additions, of which David, to his honour, never dreamed. ‘May they feel with Dathan and Abiram the damnation of Gehenna,’[1] is a fair sample of the formulæ which are found in the writings of men who, while they called themselves the servants of Jesus Christ our Lord, derived their notions of the next world principally from the sixth book of Virgil’s Æneid. And what they meant by their words their acts shewed. Whenever they had the power, they were but too apt to treat their supposed enemies in this life, as they expected God to treat them in the next. The history of the Inquisition on the continent, in America, and in the Portuguese Indies—of the Marian persecutions in England—of the Piedmontese massacres in the 17th century—are facts never to be forgotten. Their horrors have been described in too authentic documents; they remain for ever the most hideous pages in the history of sinful human nature. Do we find a hint of any similar conduct on the part of David? If not, it is surely probable that he did not mean by his imprecations what the mediæval clergy meant.

Certainly, whatsoever likeness there may have been in language, the contrast in conduct is most striking. It is a special mark of David’s character, as special as his faith in God, that he never avenges himself with his own hand. Twice he has Saul in his power: once in the cave at Engedi, once at the camp at Hachilah, and both times he refuses nobly to use his opportunity. He is his master, the Lord’s Anointed; and his person is sacred in the eyes of David his servant—his knight, as he would have been called in the Middle Age. The second time David’s temptation is a terrible one. He has softened Saul’s wild heart by his courtesy and pathos when he pleaded with him, after letting him escape from the cave; and he has sworn to Saul that when he becomes king he will never cut off his children, or destroy his name out of his father’s home. Yet we find Saul, immediately after, attacking him again out of mere caprice; and once more falling into his hands. Abishai says—and who can wonder?—‘Let me smite him with the spear to the earth this once, and I will not smite a second time.’ What wonder? The man is not to be trusted—truce with him is impossible; but David still keeps his chivalry, in the true meaning of that word: ‘Destroy him not, for who can stretch forth his hand against the Lord’s Anointed, and be guiltless? As the Lord liveth, the Lord shall smite him, or his day shall come to die; or he shall go down into battle, and perish. But the Lord forbid that I should stretch forth my hand against the Lord’s Anointed.’

And if it be argued, that David regarded the person of a king as legally sacred, there is a case more clear still, in which he abjures the right of revenge upon a private person.

Nabal, in addition to his ingratitude, has insulted him with the bitterest insult which could be offered to a free man in a slave-holding country. He has hinted that David is neither more nor less than a runaway slave. And David’s heart is stirred by a terrible and evil spirit. He dare not trust his men, even himself, with his black thoughts. ‘Gird on your swords,’ is all that he can say aloud. But he had said in his heart, ‘God do so and more to the enemies of David, if I leave a man alive by the morning light of all that pertain to him.’

And yet at the first words of reason and of wisdom, urged doubtless by the eloquence of a beautiful and noble woman, but no less by the Spirit of God speaking through her, as all who call themselves gentlemen should know already, his right spirit returns to him. The chivalrous instinct of forgiveness and duty is roused once more; and he cries, ‘Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, which sent thee this day to meet me; and blessed be thou, which hast kept me this day from shedding blood, and from avenging myself with mine own hand.’

It is plain then, that David’s notion of his duty to his enemies was very different from that of the monks. But still they are undeniably imprecations, the imprecations of a man smarting under cruel injustice; who cannot, and in some cases must not avenge himself, and who therefore calls on the just God to avenge him. Are we therefore to say that these utterances of David are uninspired? Not in the least: we are boldly to say that they are inspired, and by the very Spirit of God, who is the Spirit of justice and of judgment.

Doubtless there were, in after ages, far higher inspirations. The Spirit of God was, and is gradually educating mankind, and individuals among mankind, like David, upward from lower truths to higher ones. That is the express assertion of our Lord and of his Apostles. But the higher and later inspiration does not make the lower and earlier false. It does not even always supersede it altogether. Each is true; and, for the most part, each must remain, and be respected, that they may complement each other.

Let us look at this question rationally and reverently, free from all sentimental and immoral indulgence for sin and wrong.

The first instinct of man is the Lex Talionis. As you do to me—says the savage—so I have a right to do to you. If you try to kill me or mine, I have a right to kill you in return. Is this notion uninspired? I should be sorry to say so. It is surely the first form and the only possible first form of the sense of justice and retribution. As a man sows so shall he reap. If a man does wrong he deserves to be punished. No arguments will drive that great divine law out of the human mind; for God has put it there.

After that inspiration comes a higher one. The man is taught to say, I must not punish my enemy if I can avoid it. God must punish him, either by the law of the land or by his providential judgments. To this height David rises. In a seemingly lawless age and country, under the most extreme temptation, he learns to say, ‘Blessed be God who hath kept me from avenging myself with my own hand.’

But still, it may be said, David calls down God’s vengeance on his enemies. He has not learnt to hate the sin and yet love the sinner. Doubtless he has not: and it may have been right for his education, and for the education of the human race through him, that he did not. It may have been a good thing for him, as a future king; it may be a good thing for many a man now, to learn the sinfulness of sin, by feeling its effects in his own person; by writhing under those miseries of body and soul, which wicked men can, and do inflict on their fellow-creatures.

There are sins which a good man will not pity, but wage internecine war against them; sins for which he is justified, if God have called him thereto, to destroy the sinner in his sins. The traitor, the tyrant, the ravisher, the robber, the extortioner, are not objects of pity, but of punishment; and it may have been very good for David to be taught by sharp personal experience, that those who robbed the widow and put the fatherless to death, like the lawless lords of his time; those like Saul, who smote the city of the priests for having given David food—men and women, children and sucklings, oxen and asses and sheep, with the edge of the sword; those who, like the nameless traitor who so often rouses his indignation—his own familiar friend who lifted up his heel against him—sought men’s lives under the guise of friendship: that such, I say, were persons not to be tolerated upon the face of God’s earth. We do not tolerate them now. We punish them by law. We even destroy them wholesale in war, without inquiring into their individual guilt or innocence. David was taught, not by abstract meditation in his study, but by bitter need and agony, not to tolerate them then. If he could have destroyed them as we do now, it is not for us to say that he would have been wrong. And what if he were indignant, and what if he expressed that indignation? I have yet to discover that indignation against wrong is aught but righteous, noble, and divine. The flush of rage and scorn which rises, and ought to rise in every honest heart, when we see a woman or a child ill-used, a poor man wronged or crushed—What is that, but the inspiration of Almighty God? What is that but the likeness of Christ? Woe to the man who has lost that feeling! Woe to the man who can stand coolly by, and see wrong done without a shock or a murmur, or even more, to the very limits of the just laws of this land. He may think it a fine thing so to do; a proof that he is an easy, prudent man of the world, and not a meddlesome enthusiast. But all that it does prove is: That the Spirit of God, who is the Spirit of justice and judgment, has departed from him.

I say the Spirit of God and the likeness of Christ. Instead of believing David’s own statement of the wrong doings of these men about him, we may say cynically, and as it seems to me most unfairly, ‘Of course there were two sides to David’s quarrels, as there are to all such; and of course he took his own side; and considered himself always in the right, and every one who differed from him in the wrong;’ and such a speech will sound sufficiently worldly-wise to pass for philosophy with some critics; but, unfortunately, he who says that of David, will be bound in all fairness to say it of our Lord Jesus Christ.

For you must remember that there was a class of sinners in Judæa, to whom our Lord speaks no word of pity or forgiveness: namely, the very men who were his own personal enemies, who were persecuting him, and going about to kill him; and that therefore, by any hard words toward them, he must have laid himself open, just as much as David laid himself open, to the imputation of personal spite. And yet, what did he say to the scribes and Pharisees: ‘Ye go about to kill me, and therefore I am bound to say nothing harsh concerning you’? What he did say was this: ‘Ye serpents, ye generation of vipers, how can ye escape the damnation of hell?’

Yes; in the Son of David, as in David’s self, there was, and is, and will be for ever and ever, no weak, and really cruel indulgence; but a burning fire of indignation against all hypocrisy, tyranny, lust, cruelty, and every other sin by which men oppress, torment, deceive, degrade their fellow-men; and still more, still more, remember that, all young men, their fellow-women. That fire burns for ever—the Divine fire of God; the fire not of hatred, but of love to mankind, which will therefore punish, and if need be, exterminate all who shall dare to make mankind the worse, whether in body or soul or mind.

But David prays God to kill his enemies. No doubt he does. Probably they deserved to be killed. He does not ask, you will always remember, if you be worthy of the name of critical students of the Bible—he does not ask, as did the mediæval monks, that his enemies should go to endless torments after they died. True or false, that is a more modern notion—and if it be applied to the Psalms, an interpolation—of which David knew nothing. He asks simply that the men may die. Probably he knew his own business best, and the men deserved to die; to be killed either by God or by man, as do too many in all ages.

If we take the Bible as it stands (and we have no right to do otherwise), these men were trying to kill David. He could not, and upon a point of honour, would not kill them himself. But he believed, and rightly, that God can punish the offender whom man cannot touch, and that He will, and does punish them. And if he calls on God to execute justice and judgment upon these men, he only calls on God to do what God is doing continually on the face of the whole earth. In fact, God does punish here, in this life. He does not, as false preachers say, give over this life to impunity, and this world to the devil, and only resume the reins of moral government and the right of retribution when men die and go into the next world. Here, in this life, he punishes sin; slowly, but surely, God punishes. And if any of you doubt my words, you have only to commit sin, and then see whether your sin will find you out.

The whole question turns on this, Are we to believe in a living God, or are we not? If we are not, then David’s words are of course worse than nothing. If we are, I do not see why David was wrong in calling on God to exercise that moral and providential government of the world, which is the very note and definition of a living God.

But what right have we to use these words? My friends, if the Church bids us use these words, she certainly does not bid us act upon them. She keeps them, I believe most rightly, as a record of a human experience, which happily seems to us special and extreme, of which we, in a well-governed Christian land, know nothing, and shall never know.

Special and extreme? Alas, alas! In too many countries, in too many ages, it has been the common, the almost universal experience of the many weak, enslaved, tortured, butchered at the wicked will of the few strong.

There have been those in tens of thousands, there may be those again who will have a right to cry to God, ‘Of thy goodness slay mine enemies, lest they slay, or worse than slay, both me and mine.’ There were thousands of English after the Norman Conquest; there were thousands of Hindoos in Oude before its annexation; there are thousands of negroes at this moment in their native land of Africa, crushed and outraged by hereditary tyrants, who had and have a right to appeal to God, as David appealed to him against the robber lords of Palestine; a right to cry, ‘Rid us, O God; if thou be a living God, a God of justice and mercy, rid us not only of these men, but of their children after them. This tyrant, stained with lust and wine and blood; this robber chieftain who privily in his lurking dens murders the innocent, and ravishes the poor when he getteth him into his net; this slave-hunting king who kills the captives whom he cannot sell; and whose children after him will inevitably imitate his cruelties and his rapine and treacheries—deal with him and his as they deserve. Set an ungodly man to be ruler over him; that he may find out what we have been enduring from his ungodly rule. Let his days be few, and another take his office. Let his children be fatherless, and his wife a widow. Let his children beg their bread out of desolate places. Let there be no man to pity him or take compassion on his fatherless children—to take his part, and breed up a fresh race of tyrants to our misery. Let the extortioner consume all he hath, and the stranger spoil his labour—for what he has is itself taken by extortion, and he has spoiled the labour of thousands. Let his posterity be destroyed, and in the next generation his name be clean put out. Let the wickedness of his father and the sin of his mother be had in remembrance in the sight of the Lord; that he may root out the memorial of them from the earth, and enable law and justice, peace and freedom to take the place of anarchy and tyranny and blood.’

That prayer was answered—if we are to believe the records of Norman, not English, monks in England after the Conquest, by the speedy extinction of the most guilty families among the Norman conquerors. It is being answered, thank God, in Hindostan at this moment. It will surely be answered in Africa in God’s good time; for the Lord reigneth, be the nations never so unquiet. And we, if we will read such words rationally and humanly, remembering the state of society in which they were written—a state of society, alas! which has endured, and still endures over a vast portion of the habitable globe; where might is right, and there is little or no principle, save those of lust and greed and revenge—then instead of wishing such words out of the Bible, we shall be glad to keep them there, as testimonies to the moral government of the world by a God and a Christ who will surely avenge the innocent blood; and as a Gospel of comfort to suffering millions, when the news reaches them at last, that they may call on God to deliver them from their tormentors, and that he will hear their cry, and will help them.

___________________________________

[1] From a charter quoted by Ingulf—and very probably a spurious one.

Thank you for posting these sermons. They are very helpful. Would that we had more Christian leaders like Charles Kingsley and Bishop JC Ryle in our age!