Editor’s Note: In 1836, shortly after the Battle of San Jacinto, Sam Houston was elected as the first President of the Republic of Texas. Here we present his first inaugural address, which displays the mentality of a true Man of the West. He faces the obstacles before the new nation, and offers himself as a servant, in order to lead the people to overcome those things that stand before them. He fully accepts his role, and implores his fellow citizens to provide corrections and admonitions, when needed. It behooves us all to remember that we are imperfect beings, and therefore open to feedback.

Deeply impressed with a sense of responsibility devolving on me, I can not, in justice to myself, repress the emotion of my heart, or restrain the feelings which my sense of obligation to my fellow-citizens has inspired.…

We are only in the outset of the campaign of liberty. Futurity has locked up the destiny which awaits our people.…

If, then, in the discharge of my duty, my competency should fail in the attainment of the great objects in view, it would become your sacred duty to correct my errors and sustain me by your superior wisdom. This much I anticipate—this much I demand. I am perfectly aware of the difficulties that surround me, and the convulsive throes through which our country must pass.…

A country situated like ours is environed with difficulties, its administration is frought with perplexities.… Nothing but zeal, stimulated by the holy spirit of patriotism, and guided by philosophy and wisdom, can give that impetus to our energies necessary to surmount the difficulties with which our political path is obstructed.

A country situated like ours is environed with difficulties, its administration is frought with perplexities.… Nothing but zeal, stimulated by the holy spirit of patriotism, and guided by philosophy and wisdom, can give that impetus to our energies necessary to surmount the difficulties with which our political path is obstructed.

By the aid of your intelligence, I trust all impediments in our advancement will be removed; that all wounds in the body politic will be healed, and the Constitution of the Republic will derive strength and vigor equal to all opposing energies.…

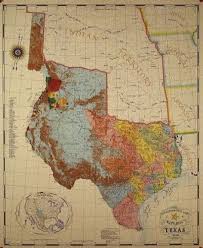

A subject of no small importance is the situation of an extensive frontier, bordered by Indians, and open to their depredations. Treaties of peace and amity, and the maintenance of good faith with the Indians, present themselves to my mind as the most rational grounds on which to obtain their friendship. Let us abstain on our part from aggressions, establish commerce with the different tribes, supply their useful and necessary wants, maintain even-handed justice with them, and natural reason will teach them the utility of our friendship.…

Admonished by the past, we can not, in justice, disregard our national enemies; vigilance will apprise us of their approach, a disciplined and valiant army will insure their discomfiture.… We must keep all our energies alive, our army organized, desciplined, and increased agreeably to our present necessities. With these preparations we can meet and vanquish despotic thousands. This is the attitude we at present must regard as our own.…

The course our enemies have pursued has been opposed to every principle of civilized warfare—bad faith, inhumanity, and devastation marked their path of invasion. We were a little band, contending for liberty; they were thousands, well appointed, munitioned, and provisioned, seeking to rivet chains upon us, or extirpate us from the earth. Their cruelties have incurred the universal denunciation of Christendom. They will not pass from their nation during the present generation.…

At this moment I discern numbers around me who battled in the field of San Jacinto, and whose chivalry and valor have identified them with the glory of the country, its name, its soil, and its liberty.… It now, Sir, becomes my duty to make a presentation of this sword—this emblem of my past office!…

I have worn it with some humble pretensions in defence of my country; and should the danger of my country again call for my services, I expect to resume it, and respond to that call, if needful, with my blood and life.