Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Makers and Romance of Alabama History, by B. F. Riley (published 1914).

No more romantic character figured in the early days of Alabama history than General Sam Dale. Cool as an ocean breeze, and fearless as a lion, his natural qualifications fitted him for the rough encounters of a pioneer period. Like an ancient Norseman he sought danger rather than shunned it, and hazard furnished to him a congenial atmosphere. He was born for the perils of the frontier, and his undaunted spirit fitted him for reveling in the stormy scenes of early Indian warfare.

A native of Virginia, Dale was taken to Georgia in early childhood, and there grew to early manhood. From his earliest recollections he was familiar with the stories of the lurking savage and the perils of the scalping knife and tomahawk. He was therefore an early graduate from the border school of hunting and Indian warfare.

When Dale removed to Alabama in the budding period of manhood he had already won the reputation of being the most daring and formidable scout and Indian fighter of the time. In numerous encounters he had been a distinguished victor. Six feet two inches high, straight as a flagstaff, square shouldered, rawboned and muscular, with unusually long and muscular arms, he was a physical giant and the terror of an Indian antagonist. By his courage and intrepidity, he excited the regard even of the Indians, who called him “Sam Thlucco,” or Big Sam.

The qualities possessed by Dale may be illustrated by the revelation of one or two of his daring feats. Appointed a scout at Fort Matthews on the Oconee River, in Georgia, which fort was under the command of the famous Indian fighter, Captain Jonas Fauche, Dale slid with stealthy movement through the country, and spied out the whereabouts and plans of the Indians. Once while at a great distance from the fort, he was bending over a spring of water to drink, two Muscogee warriors sprang from behind a log, and leaped on Dale with tomahawks upraised. With entire coolness of mind he pitched one of them over his head, grasped the other with his left hand, and with his right plunged his knife into his body. Quick as thought the other recovered himself, and rushed with madness on Dale just in time to meet another thrust from his blade, and both lay dead at his feet. Bleeding from five wounds which he had received in the combat, Dale retraced the trail of the Indians for nine miles through the woods, and when he came to the edge of their encampment he found three brawny warriors sprawled on the ground asleep, while in their midst there sat a white woman, a prisoner, with her wrists tied. He deliberately killed all three as they slept, and cut the thongs of the prisoner. Just then a stalwart Indian sprang from behind a tree with a wild yell, and with a glittering knife ready to bury it into Dale’s body. Dale weakened by his wounds and his exhausting march, was thrown to the ground by the Indian, who had him in such a position that within a moment more he would have made the fatal stab had not the woman quickly seized a tomahawk and buried it in the brain of the Indian. The woman was quietly escorted back to the fort and returned to her home.

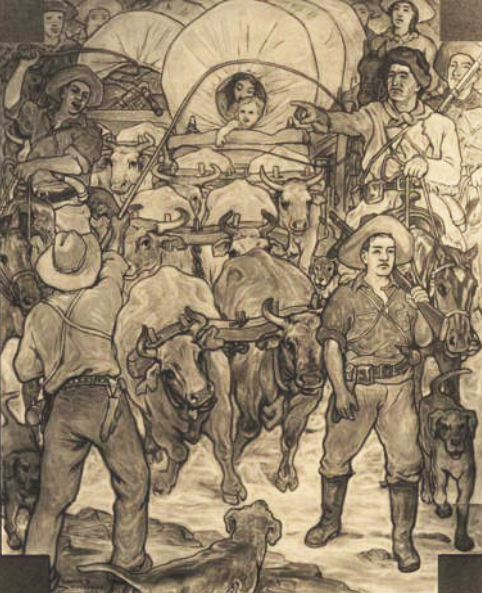

Peace having been made, Dale betook himself to trading with the Indians, exchanging calicoes, gewgaws, ammunition, and liquor, for peltry and ponies. His profits would have been enormous had Dale not been the spendthrift that he was. But like many another, he never knew the value of a dollar till he was in need. His trading led him across the Chattahoochee into the Alabama territory in 1808, at which time we find him among the earliest immigrants to this region. He was most valuable as a guide in directing for years bodies of immigrants from Georgia to Alabama. He was at Tookabatchee and heard the war speech of Tecumseh which precipitated the war in Alabama, and straightway gave the alarm of approaching hostilities to the inhabitants. A long and brilliant series of daring exploits marked the years of the immediate future of Dale’s eventful life.

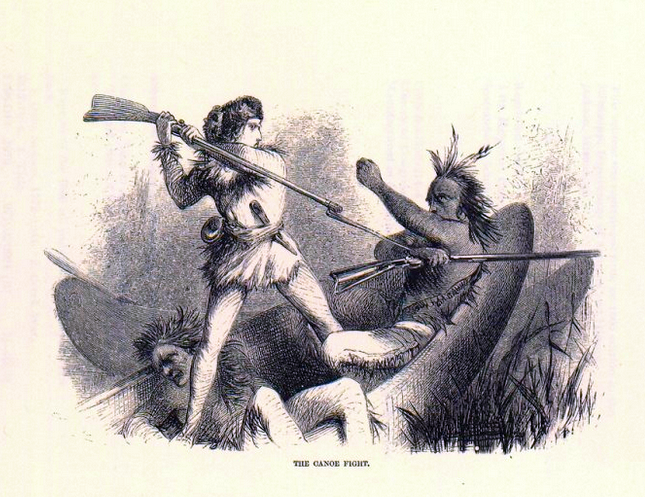

Perhaps the most noted of his feats was that of the famous “canoe fight,” on the waters of the Alabama River. This was a thrilling encounter, and is inseparable from the great achievements which adorn the state’s history. It is too long to be related in detail, and only the outline facts can here be given. With two men in a canoe, Austill and Smith, and the faithful negro, Caesar, to propel the little boat, Dale sallied forth on the bosom of the river to encounter eleven Indian warriors in a larger boat. As the boat which bore the Indians glided down the river, the one containing the three whites shot out from under a bluff, and was rowed directly toward the Indians. Two of the Indians sprang from the boat, and swam for the shore. Caesar, the negro, who paddled the canoe of the whites, was bringing his boat so as to bear on the other, that they would soon be alongside, which so soon as it was effected, the negro gripped the two and held them together while the fearful work of slaughter went on. The result of the hand to hand engagement was that the nine Indians were killed, and pitched into the river, while the whites escaped with wounds only.

In the early territorial struggles General Dale was engaged partly as an independent guerilla, and partly under the commands of Generals Jackson and Claiborne. At the close of hostilities Dale took up his residence in Monroe County from which he was sent as a representative to the legislature for eight terms. In recognition of his services the legislature granted him an appropriation amounting to the half pay of a colonel in the regular army, and at the same time gave him the rank of brigadier general, in which capacity he was to serve in case of war. Later, however, the appropriation was discontinued because of a constitutional quibble, when the legislature memorialized Congress to grant an annuity to the old veteran, but no heed was given to the request.

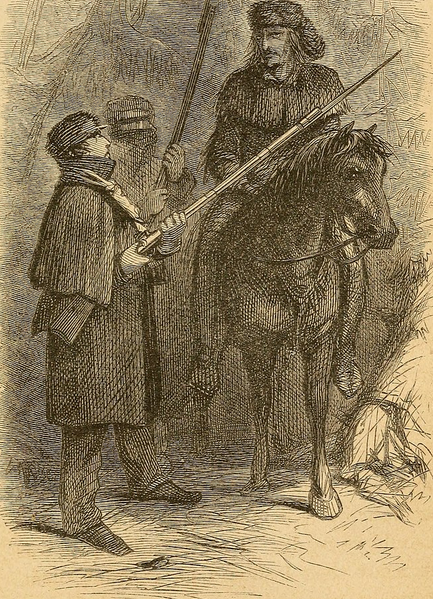

In order to procure some compensation for his services, General Dale was induced by his friends to go to Washington, and during his stay at the national capital, he was entertained by President Jackson. Together the two old grizzled warriors sat in the apartments of the president, and while they smoked their cob pipes, they recounted the experiences of the troublous times of the past.

General Dale served the state in a number of capacities additional to those already named. He was a member of the convention which divided the territories of Alabama and Mississippi, was on the commission to construct a highway from Tuskaloosa to Pensacola, and assisted in transferring the Choctaws to their new home in the Indian territory.

His last years were spent in Mississippi, where he served the state in the legislature. He died in Mississippi in 1841. His biographer, Honorable J. F. H. Claiborne, says that a Choctaw chief, standing over the grave of Dale the day after his burial, exclaimed: “You sleep here, Sam Thlucco, but your spirit is a chieftain and a brave in the hunting grounds of the sky.”

Just want to point out that getting bayonetted would really, really suck.