Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Heroes of Aviation, by Laurence La Tourette Driggs (published 1918).

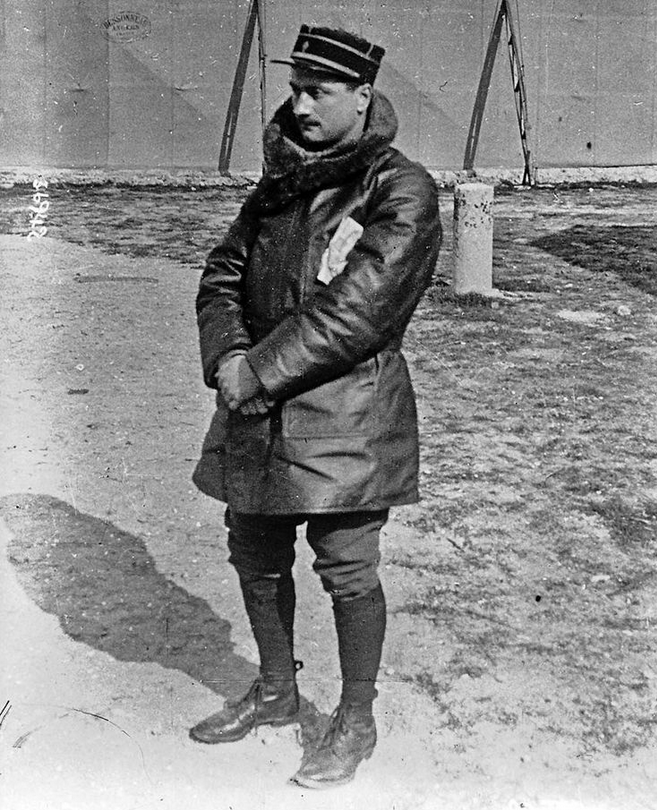

As the name Wright is to America, so is the reputation in France of the celebrated aviator, Roland Garros.

Even before the war came to emphasize the importance of flying Garros occupied perhaps the most conspicuous position in French aviation. Every air contest of importance in Europe found him entered, and usually a victor. He had given exhibitions through out the United States in 1911. He was the first to fly over the Mediterranean Sea. With Beaumont or Pegoud or Brindejonc de Moulinais he shared the prizes of the great European Circuit, the race from Paris to Rome, from Paris to Madrid, and in 1911 he won the Grand Prix d’Anjou.

At the mobilization of the air forces of France in August, 1914, Roland Garros was in Germany. Scenting the possibility of danger he did not wait even to collect his belongings, but evading his acquaintances took the first train to Switzerland and hastened on to Paris.

Upon his arrival he reported for immediate service and was attached forthwith to the squadron of notables containing besides himself Eugene Gilbert, Marc Pourpe, Maxime Lenoir, Armand Pinsard and Captain de Beauchamp — Escadrille M. S. 23.

The early months of war-aviation revealed many startling truths concerning the aeroplane. It could carry messages quicker than any other means where wires were not laid. It could fly over enemy positions and come back with the report of observations made in a manner that revolutionized modern warfare. It could drop bombs and literature into enemy camps, and shots from the ground were ludicrously ineffectual against its maneuvering.

All these qualifications were immensely gratifying to Garros and his comrades, many of whom had for years been preaching to a deaf public the possibilities of aviation in commerce and in war. All these possibilities had been foreseen by the veteran Garros. But, one question undoubtedly had been settled in actual warfare that had previously been highly speculative – it appeared virtually impossible during the first month of the war to shoot down an aeroplane in flight either with guns on the ground or guns mounted on other aeroplanes. Bullets from the ground were wasted against the swiftly moving machines. Even if a lucky shot did strike them it passed through the wings with out inflicting serious injury. This method of combating enemy machines might as well be abandoned.

There remained the possibility of mounting a machine gun on an aeroplane for the pilot’s use in such a manner that the stream of issuing bullets would not hit the tractor propeller. To this problem Garros set his inventive mind.

In February, 1915, after many weeks of patient experimenting, Garros petrified his aeroplane enemies by suddenly appearing among them with his new invention. From the very nose of his aeroplane, hitherto considered the safest blind spot of all, deadly streams of bullets poured forth. In eighteen days Garros shot down five incredulous Huns. His success was instantaneous and complete.

France immediately set about duplicating the device of Garros on all fighting machines. It was a point of decided superiority over the German airmen. But alas! By a strange fatality, Roland Garros himself was brought down on the day of his last victory, April 19, 1915, and fell a prisoner into the hands of the Huns. Unable to destroy his machine before he was captured, Garros suffered the mortification of giving to his enemies the very invention over which he had so long labored for their destruction.

His capture was due primarily to the very precise methods Garros adopted in his daring bombing raids. He had invariably returned home from these raids crowned with success. Depots, bridges, factories, and supply stations he had repeatedly set on fire and destroyed, always by the same method.

Approaching his objective from a height of ten or twelve thousand feet, Garros would cut off his motor and descend through the defending but futile shells until his machine was within a hundred feet or so of his target. Then, pulling back on his lever, he released his bombs so near the roof that a miss was impossible. Switching on his motor again he would brave the shots from below and gaily make his way back into the French lines.

On April 19, he flew over into the enemy camp and descending low upon a freight train of supplies entering Courtrai, he dropped his bombs with his usual precision. He had descended with idle motor from a very high altitude. After watching for a moment the effect of the explosions Garros blandly turned on the spark and set his face towards home.

But the engine did not pick up! Not a single cylinder uttered a reassuring cough. The engine was cold or filled with oil, or perhaps the spark plugs were faulty. Every second the aeroplane was dropping nearer the earth.

Frantically Garros worked the throttle and nursed along his machine, endeavoring by every means to put some life into the stubborn motor. But in vain! His aeroplane dropped heavily to earth in the very midst of his enemies, and he was captured even before he was able to wreak his vengeance, so richly deserved, upon his faithless engine. He was captured in a ditch where he had concealed himself at the last moment after hastily attempting to fire his aeroplane. The fire did not destroy the machine but was quickly extinguished by the Huns.

His great discovery was thus presented personally by himself to his enemies. And none too slowly did they turn it to their own advantage.

The “King of the Air” was in their hands. Twice before the newspapers of Europe had announced with fervid details the story of Garros’ death. This time however his fate had been witnessed by several of his comrades, and France knew that her famous “bird man” was indeed a prisoner in Germany.

For weeks no news came as to whether Garros was dead or wounded. His captors not only concealed all news of him but subjected him to many cruelties and indignities. He was confined for some weeks in the prison at Magdeburg, but later was liberated and given comparative freedom in the prison stockade at Cologne. So precious did the Huns consider this celebrated Frenchman, however, and so apprehensive were they of his ability to make his escape that they compelled Garros to sign his name to a register every thirty minutes of the day when he was not under lock and key!

For over two years this strict scrutiny was unrelaxed. In the meantime Lieutenant Marchal, the hero of the longest aeroplane flight in the history of the war — that from the French lines to Berlin where Marchal dropped leaflets into the German capital from his aeroplane and then flew onwards to within forty miles of the Russian frontier, a total distance of 750 miles without stopping — Lieutenant Marchal, through the exhaustion of fuel, had been compelled to drop into the German lines, where he was captured. He was sent to the same prison camp which contained Garros.

In January, 1918, France resounded with the news that Garros and Marchal had escaped from Germany and were in England. For military reasons the details of their escape cannot be given. Both airmen passed over into France and again entered into the service of their country.