Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Lectures on Foreign History, 1494-1789, by J. M. Thompson (published 1925).

I

The dagger which killed the best of French kings brought the son of his old age, an infant of eight, to the throne, and put the government of the country into the incompetent hands of his Italian widow, Mary de Medici. While the young Gustavus was learning languages, and the art of government, Louis XIII spent his youth hawking, cock-fighting, and playing cards. He was soon tired of his tutor, and said, ‘If I give you a bishopric, will you shorten my lessons?’ [Herouard].

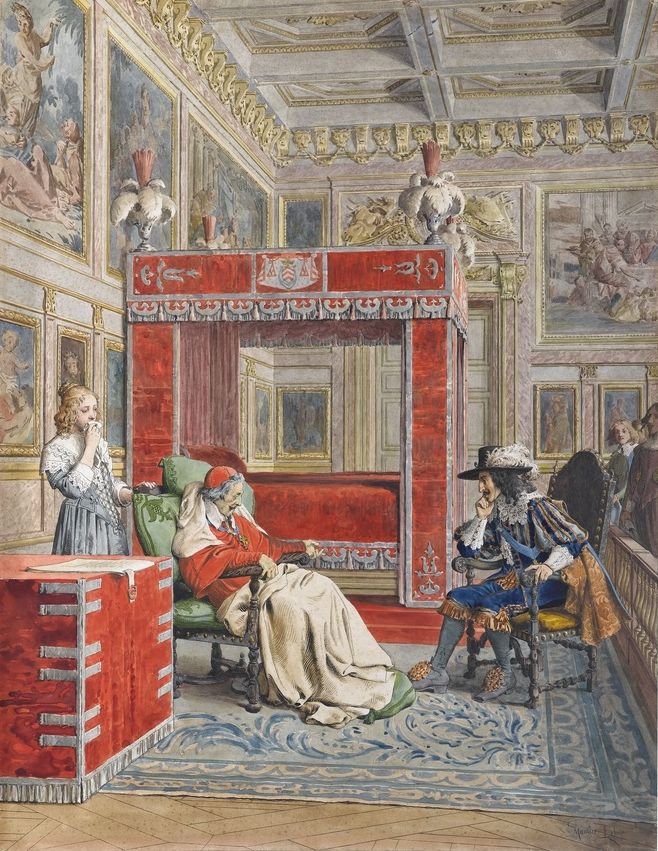

The little that the French princes learnt about government, they taught themselves, by the experiment of governing. At sixteen Louis determined to be King, with the help of his favourite falconer, one Luynes. It was not a success; and nobody could have foreseen anything but another period of French eclipse, or a recurrence of the Wars of Religion, when in 1624 Richelieu became Minister. Under this man the next eighteen years became one of the greatest periods in the history of France. It was Richelieu who fixed the lines upon which French development was to run for more than 150 years. It was Richelieu who created the Ancien Régime, the social and political system of Louis XIV and XV, which was not to be broken up until the French Revolution.

II

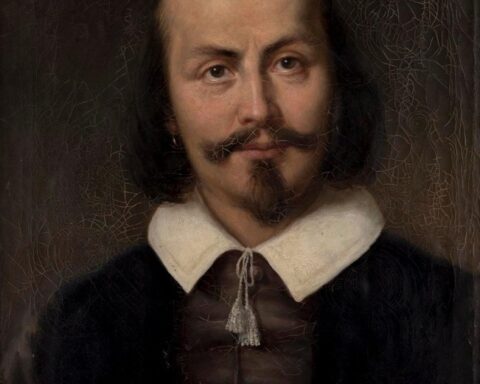

A bishop from the age of 22, Richelieu had the mind of a layman. For twenty years a Cardinal, he was yet essentially a general and a statesman. The author of more than one theological treatise, his works were Laws and Regulations. Everything he did was inspired by a single aim. He believed in France, he believed in the Monarchy, and he believed in the Church as the support of the Throne. His one ambition was to make France great, and he would allow no motive to override raison d’état—the interests of his country. We can read this clearly enough between the lines of the Cardinal’s ‘Memoirs,’ which give a detailed account of his ministry year by year. There is no need to draw on the ‘Maxims of State,’ or ‘Political Testament,’ published under his name, but of doubtful authenticity. This book, however, is prefaced by a ‘Short account of the great acts of the King’ which is certainly genuine, and in which Richelieu sums up his policy in his own words. ‘When your Majesty,’ he writes, ‘resolved to give me at once both a seat in your Councils and a large share of your confidence in the conduct of affairs, I can only say that the Huguenots shared the State with you, that the nobles behaved as though they were not your subjects, and the most powerful provincial governors as though they were independent rulers . . . I promised your Majesty to employ all my industry, and all the authority you pleased to give me, in destroying the Huguenot party, humbling the pride of the nobles, reducing all your subjects to obedience, and exalting your name among foreign nations to the high place it deserved to hold.’

The four aims here mentioned are really two :—at home, a strong government, and the repression of all independent minorities under the absolute authority of the Crown; and abroad, ‘la gloire’—an aggressive foreign policy, directed towards French predominance in Europe. According to good observers, these are the two political principles nearest the heart of the French people—then and now. Was Richelieu a great man? At any rate he was a great Frenchman.

French foreign policy has always been affected, quite as much as our own, by the geographical position of the country; but with an opposite result. Our only frontier towards the Continental Powers—the English Channel—has enabled us, time after time, to keep out of European quarrels. The French continental frontier—at least three times as long as ours—has made it impossible for them to do so. Towards Italy and Spain it is a mountain wall, almost as inviolate as the Channel. But between Basle and Boulogne, roughly a half of the whole land frontier, there are only two districts—the Vosges and the Ardennes—where an invader could not easily enter from the east, and find an open road to Paris. There are two ways of securing such a frontier. One is to push it as far back as possible, and to fortify it: the other is to weaken and divide the enemies who might attempt an attack. France did both. The object of her wars, from Francis I to Louis XIV, was to push back her frontier in the east and the north-east till it coincided with the ‘natural frontier’ of the country, the line of greatest resistance—that of the Rhine and Scheldt. The object of her diplomacy, from beginning to end of our three hundred years’ period, was to play off one power in central Europe against another, so that none should be strong enough to attack her. Richelieu was the first great exponent of this policy.

What Power did he most fear? The answer is simple—the Hapsburgs. Two Hapsburg dynasties had reigned in Europe since the abdication of Charles V. One branch of the family was at this moment making a last attempt to reconquer Germany for Austria and for the Pope. When Richelieu came into power in 1624, Ferdinand was already master of Bohemia and of the Palatinate. Within five years he had defeated Denmark, seized the Baltic ports, and published the Edict of Restitution. Whilst this branch of the family strengthened Germany, the other weakened France. In the Pyrenees, in north Italy, in Burgundy, in Lorraine, and in the Netherlands, France felt itself encircled by Spanish troops. At any moment the two Hapsburg dynasties might reunite, and form an overwhelming power. It was the situation that Francis I had to face, but time had made it more dangerous.

What was Richelieu’s plan for dealing with the Hapsburg menace? Until 1628 he was too much occupied by troubles at home to intervene abroad. But in that year the capture of La Rochelle broke the back of the Huguenot revolt; and early in 1629 he drew up a long document which he headed ‘Advice to the King,’ and which showed clearly what his policy was going to be. ‘Now that La Rochelle is taken,’ he writes, if the King wants to make himself the most powerful monarch and the most highly esteemed prince in the world, he must consider before God, and examine carefully and secretly, with his faithful servants, what is needed in himself, and for the reform of the State. As to the State, its interests fall under two heads—internal and external. As regards the first, it is necessary before all things to destroy the heretical rebellion . . . to pull down all fortresses which do not protect frontiers, or command river-crossings, or hold in check mutinous or troublesome cities . . . Corporations which oppose the welfare of the kingdom by their pretended sovereignty [e.g. the Parlements] must be humbled and disciplined. Absolute obedience to the King must be enforced upon great and small alike . . . As regards external affairs, it must be our fixed policy to check the progress of Spain. Wherever that nation aims at increasing its power and extending its territory, our one object must be to fortify and dig ourselves in, whilst making open doors into neighbouring states, so that we can safeguard them against Spanish oppression, whenever occasion may arise. In order to effect this, the first thing to be done [this is remarkable] is to become powerful at sea; for the sea is an open door to every state in the world. Secondly, we must think of fortifying Metz, and, if possible, of advancing to Strasbourg, so as to command an entry into Germany: but this will take time, and must be done with great caution, tact, and secrecy.’

It is an extraordinary tribute both to the genius of Richelieu, and to the consistency of French statesmanship, that one or another item of this programme—at home, religious uniformity, the disablement of the nobles, and centralized government; abroad, an antiHapsburg policy, with the strengthening of the frontiers, and the advance to the Rhine—reappears fifty years later in the policy of Louis XIV, a hundred years later in the policy of Fleury, and a hundred and fifty years later in the policy of Vergennes. The one lesson which Richelieu’s successors would not learn from him—and their neglect of it was in the long run fatal to their country—was the importance of sea power.

III

Such was Richelieu’s plan in 1629. His opportunity for carrying it out came in the very next year. In 1630, as we have seen, Wallenstein’s Baltic campaign, and Ferdinand’s Edict of Restitution, brought Gustavus Adolphus into Germany. They also made the Emperor’s own allies, the Catholic League, suspicious of his intentions. Richelieu had thus two weapons that he could use against Austria: and he used them both. His ambassador, Charnacé, was instructed to offer Gustavus financial support for his attack on the Emperor. His secret agent, Father Joseph, was sent to the Diet of Ratisbon to embitter the Catholic League against Ferdinand, and to intrigue for the dismissal of Wallenstein. Both negotiations were successful. Wallenstein was dismissed, and his army disbanded, at the very moment when Gustavus landed in Germany. Tilly was left to face the invaders alone. By the treaty of Bärwald (January, 1631) Richelieu agreed to pay the King of Sweden a large sum down, and an annual subsidy, so long as he kept a stipulated number of troops in the field. The object of the Franco-Swedish alliance was declared to be the protection of their common friends [the Protestants—though France was a Catholic country], the security of the Baltic, the freedom of commerce, the restitution of the oppressed members of the Empire [e.g. the Elector Palatine], and the destruction of the newly-erected fortresses in the Baltic, the North Sea, and the Grisons territory [in the Alps—a French demand, to which I will return later], so that all should be left in the state in which it was before the German war began’ [Fletcher]. Gustavus was not to interfere with the Imperial constitution or with the Catholic religion in any districts that he might conquer, and he undertook to observe friendship and neutrality towards Bavaria and the Catholic League, if they did so too. This was not that any Catholic scruples deterred Richelieu, but because it was part of his policy to keep Maximilian from throwing in his lot with Ferdinand. Gustavus tied his own hands more than he liked by these terms: but he gained what was of immense importance to him—French prestige, French diplomacy, and French gold.

This was in the spring of 1631. Early in September Gustavus defeated Tilly’s army at Breitenfeld. Then, instead of marching straight on Vienna, as Richelieu had hoped he would do, he turned southwest towards the Main valley, and the States of the League. The same month he was at Wurtzburg, the next at Frankfort, the next at Mayence. By the end of the year he was holding his winter court in the centre of the territory which Richelieu had wished him to avoid, and maintaining his army at the expense of the League, which Richelieu had hoped to keep neutral.

What was he to do next? With regard to the Emperor, he might rest content with what he had done, and make such terms as to gain all that Sweden itself needed. But he could not give up his crusade. ‘Our opinion is,’ he writes to Oxenstjerna, ‘that no reconciliation can be accepted unless a general peace, and one relative to religion, be signed for all Germany, so that our neighbours [e.g. the Elector Palatine, who was staying with him at Mayence] be reinstated in their possessions, and we ourselves live in security . . . To accomplish this result we have no other means than to attack the Emperor in his dominions, as well as the Catholic clergy, who hold to him: for if we can enter into his hereditary territories, to possess ourselves of his resources, and to take from him the contributions which he draws from the Protestants, so that the whole burden of the war falls on the Catholic clergy, then we can dictate the terms of a glorious peace for ourselves and for our brethren’ [Stevens].

But what about his obligations to Richelieu, and the interests of France? While Gustavus was at Mayence, during the winter of 1631, some of his troops crossed the Rhine. Richelieu sent an envoy to protest. The King’s reply was hardly diplomatic. ‘His Majesty answered,’ says Monro (he was a bit of a Tartar himself, and may be exaggerating Gustavus’s military brusqueness), ‘he did but prosecute his enemy, and if his Majesty of France was offended, he could not help it; and those that would make him retire over the Rhine again, it behoved them to do it with the sword in their hand; for otherwise he was not minded to leave it, but to a stronger. And if his Majesty of France should anger him much, he knew the way to Paris, and he had hungry soldiers [who] would drink wine and eat with as good a will in France as in Germany.’ Richelieu began to find Gustavus a difficult ally. But he kept his temper, continued to pay the subsidy he had promised, and exerted himself to prevent any attack on the Catholic League. After long negotiations, all the members of the League except one accepted the Swedish terms, and remained neutral. The one who refused was, however, the most important—Maximilian of Bavaria. He preferred to stand by the Emperor.

From Mayence to Vienna the way is through Bavaria. In the spring of 1632 Gustavus marched to Nuremberg, which declared for him, crossed the Danube at Danauwörth, and defeated Tilly at the passage of the Lech. Soon he was in occupation of Munich, the Bavarian capital, and planning an advance on Vienna. But now Wallenstein, recalled by the Emperor, and reappearing with a fresh army in the direction of Saxony, forced him to return to Nuremberg, and invested the town. Unable to drive off the besiegers, and fearing for his communications, Gustavus forced his way out to the north. In November the two armies met at Lützen, not far from Breitenfeld. They fought all day; but when at last the Imperial army retired in disorder, Gustavus was dead. ‘This Magnanimous King,’ writes Monro, ‘for his valour might have been well called the Magnifique King, and holden for such, who while as he once saw appearance of the loss of the day, seeing some forces beaten back, and some flying, he valorously did charge in the middest of his enemies, with hand and voice, though twice shot, sustained the fight, doing alike the duty of a soldier and of a king, till with the loss of his own life he did restore the victory, to his eternal credit, he died standing, serving the public, Pro Deo et religione tuenda; and receiving three bullets, one in the body, one in the arm, and the third in the head, he most willingly gave up the ghost, being all his time a King that feared God and walked uprightly in his calling; and as he lived Christianly, so he died most happily, in the Defence of the Faith.’

They took his body to a little village church close by the battlefield, where the village schoolmaster read the burial service to a congregation of mounted men. Then to the schoolmaster’s house, where that good man, who was also a carpenter, made a rough coffin, in which they carried the body home to Sweden, and buried it in Riddarholm church at Stockholm, under a canopy of tattered flags.

IV

In 1635, three years after the battle of Lützen, begins the fourth and last period of the Thirty Years’ War. Since the death of Gustavus little that is interesting and nothing that is creditable seems to be left in it. The Swedes have been defeated at Nördlingen (1634), but their army is in the field, and their garrisons hold the Baltic ports. The Protestant princes have been forced to make a peace at Prague (1635), but they do not intend to keep it. Richelieu is now in a position to act more openly. He has dealt with the Huguenots and the nobles at home. He has built up the largest army France has ever had. He makes fresh alliances with Sweden, with the United Provinces, with some of the German princes, notably Bernard of Saxe-Weimar, leader of an independent army, with the Swiss, and with the Duke of Savoy. Thus secured in every possible quarter, he declares war against Spain (1635).

The fighting that lasted from 1635 to 1648 belonged less to the Thirty Years’ War between the Catholics and the Protestants than to the three hundred years’ war between the Bourbons and the Hapsburgs. It was German only in the sense that Germany was the battlefield. It began, indeed, with a Spanish invasion of France that was within an ace of reaching Paris, and ruining the prestige of Richelieu. But between 1637 and 1642 French troops captured Artois in the north and Roussillon in the south; and in 1643, when Richelieu was dead, and Louis XIII dying, the victory of Rocroi made the reputation of the royal army, as the victory of Valmy made the reputation of the Republican army 150 years later. Other successes followed at Fribourg (1644) and at Nördlingen (1645). But it was not until 1648 that a concerted attack on Vienna by the Swedes through Bohemia, and by the French through Bavaria, tried four times in eight years, was at last successful, and Ferdinand III, who had succeeded his father in 1637, was forced to make peace with Louis XIV.

The state of Germany in 1648 has been described as ‘the most appalling demonstration of the consequences of war to be found in history’ [C.M.H.]. This was written before 1914—before Belgium or northern France, before the Russian retreat in Poland, or the Austrian occupation of Serbia. But I doubt whether any single country suffered so much, even in the last war. In Bohemia, out of 35,000 villages, only 6,000 were left standing, and three-quarters of the population had disappeared. In Württemberg one man in six remained, in the Lower Palatinate only one in ten. The total population of the Empire was reduced from over sixteen to under six millions:—there were 350,000 war casualties; the rest was due to famine, pestilence, and emigration. Agriculture was ruined. War taxation had reduced the peasantry to serfdom; and there was no more security for property than for life. A third of the land in north Germany had fallen out of cultivation: instead of sheep there were wolves, instead of fields there were forests. The walled towns had suffered less than the open country. But they were crowded with refugees, their industries destroyed, and their trade captured by foreigners. Morally, too, Germany suffered all the worst effects of a religious, civil, and mercenary war. Church fought against church, and state against state. Political tyranny was embittered by ecclesiastical persecution. Foreign armies lived on the country, carrying about with them hordes of women and children and other non-combatants—for with the army, if anywhere, food might be found—and creating a state of licence and anarchy seldom equalled in later wars. Schools and universities almost disappeared. Cruelty and superstition so flourished that in the two years 1627-8 the Bishop of Wurtzburg put to death 9,000 supposed wizards and witches, and 1,000 were burnt in one district of Silesia in 1640-1.

What gains, if any, there may have been to compensate for this weight of human misery, must be considered when we come to the Peace of Westphalia. At the moment all we can see is that Germany in the seventeenth, like Italy in the sixteenth century, has suffered for its disunity, and become the prey to internal jealousy and external greed. Its disunity remains, and in an aggravated form: it has become endemic. The only real gainer by the Italian wars was Spain: the only real gainer by the Thirty Years’ War was France.

V

In the middle of the Alps, running south-westwards to the head of Lake Como, is a mountain valley called the Valtelline. It is only sixty miles long and three miles wide: but in the early seventeenth century it was one of the most important spots in Europe. How was this? First, though its population was only 30,000 or so, they were all fighters, and the place had been well known to the recruiting-sergeants of France, Spain, and Venice. Secondly, though fierce, the valley was not free. It had once belonged to Milan: it now belonged to the Grisons (or ‘Grey Leagues’)—a confederation of Swiss villages, whose rule was tyrannous and unpopular. Moreover, the valley people were mainly Catholic, but their rulers were Protestants. Thirdly,—and this was the crux—since France blocked the western passes, and Venice held the lower Adige valley, the Valtelline had become the main route between Germany and north Italy. That is to say, its possession was vital to Spain, which held Milan, and sent its troops by this route to the Rhine valley and the Netherlands. It was equally a point of French policy to close the pass, and break the enemy’s line of communications. With so many interests crossing one another, the position of a ruler in the Valtelline must have been rather like that of a policeman on point duty at Carfax.

The religious quarrels had led to rioting and massacre in 1619. The international struggle for the pass had ended in the occupation of the valley by the Spaniards in 1620; and though they promised to evacuate it the next year, it was obvious that they would only do so under compulsion. When Richelieu became minister in 1624, negotiations were still going on. In July of that year a meeting of the State Council was held, at which he gave his views on the whole situation. The Memorandum was reprinted in his Memoirs, and it gives so good an idea of the scope and character of his diplomacy, that I want to summarize it here.

First, he says, Spain has behaved very badly in the whole matter. In spite of its promise to evacuate the place, one of the Commissioners of the Duke of Feria and the Archduke Leopold had said, not long before, to persons worthy of belief, that, if they could get six months’ grace, all the Kings in the world could not make them loosen their hold on the Valtelline.’ Secondly, the Grisons are ancient allies of the King of France, and he has a perfect right to help them to defend their property—though the Swiss have only themselves to thank for their present troubles, since they have been intriguing with Spain and Venice against France. Next—this is so characteristic that I will quote Richelieu’s own words— ‘The interest of France and of the whole of Europe is involved: the union of the separated states of the house of Austria outbalances the power of France, which secures the liberty of Christianity.’ Fourthly, an argument for active intervention: if we do nothing, Spain will think us afraid, and our allies will desert us. Fifth, the worst maladies are those with complications. The Valtelline business is one of these. It involves questions in Switzerland, Flanders, Germany, and France itself—for we must not give an opening to the Huguenots or financiers for making trouble at home. So we must begin by sending the nobles back to their provinces, fortifying the frontiers, and raising enough troops to keep both nobles and Protestants quiet. Then, sixthly, we must try to get the Pope to persuade the Spaniards to give up the Valtelline: if he won’t, the Grisons must do their part, and the Swiss must help them. Next, to prevent Spanish troops being sent from Milan, or Spanish gold from Genoa, we must attack the Genoese in the name of Savoy (the Zucarel dispute will serve as a casus belli). Then we must keep Spain busy in Flanders by trying to relieve Breda [which the Spaniards were besieging], and by getting the United Provinces to make fresh efforts. Ninth, to keep the Catholic League in Germany employed, we must urge the King of England to finance the King of Denmark for the recovery of the Palatinate [which Tilly had just conquered for Ferdinand], and we must use Mansfeld’s army for the same purpose. But we mustn’t overdo this, or exasperate the League; so it will be best to hold Mansfeld back for six months (England paying his expenses), whilst we try to make Maximilian of Bavaria come to terms with James of England, and with his son-in-law, the Elector Palatine. In all this the Pope will be on our side, because he can see that our whole policy is in the interests of religion, and because his political position, like that of other princes, requires a balance of power between the Bourbons and the Hapsburgs. Finally, we must act with dexterity, to avoid an open break with Spain, which might be fatal to Christianity. But if the Spaniards take offence at our helping the Grisons, everyone will be against them, all Christendom will be on our side, and we can hope for a good and glorious success.’

I need not follow out Richelieu’s attempts to put this policy into practice. We have seen some of them from a rather different angle in dealing with the last part of the Thirty Years’ War. As to the Valtelline, France won it in 1635; in 1639 she lost it again; in the end the valley people gained religious toleration, but remained under Spanish rule. I have drawn attention to this bit of history mainly to illustrate Richelieu’s grasp of international politics, and to show how his diplomacy followed out a central idea—that of breaking through the Hapsburg ring round France—into almost inconceivable ramifications. He is a master player at the game of statesmanship; studying his opponent’s mind, and knowing his own; realising just what use can be made of each piece on the board; calculating in advance the effect of each move, and of others that will follow from it; co-ordinating every means to the single end of winning the game.

VI

At the head of Richelieu’s home policy we may put his own maxim, ‘Il faut pourvoir au coeur’ — ‘the health of a country depends upon its heart.’ His aim at home was the counterpart of his aim abroad. His constructive mind, which saw how every situation in Europe might be made to serve the interests of French foreign policy, saw also how every class in France might be made to serve the interests of the French crown. Unity was his watchword: and in France as he knew it the only practicable centre of unity was the throne. So he set himself to destroy political independence at home, as a step towards destroying political rivalry abroad. We have seen how, from 1629 onwards, he carried out his policy against Spain and Austria. We must now see how he gained freedom to do so by destroying the political power of the Huguenots and of the French nobility between 1624 and 1629.

When Richelieu became Minister the position of the Huguenots was still regulated by the Edict of Nantes. This settlement bore clear marks both of the genius of its author, Henry IV, and of the difficult situation in which it had been drawn up. It gave the Huguenots not only a (limited) freedom of worship and citizenship, which was their due, but also a political and even military independence, which they had been strong enough to demand. Henry’s own qualities as ruler, and the exhaustion of the country after thirty years of civil war, had made this arrangement workable. But since his death it had not been honestly carried out by either side. The Catholic majority used their superior position to practise indirect persecution of the Protestants: the Huguenot minority used their synods and cities of refuge to organize opposition, not merely against the Catholics, but against the crown. Richelieu was not a religious, but he was a political persecutor. He could tolerate a church within a church, but he could not tolerate a state within a state. He determined to crush the political independence of the Huguenots.

In 1625, when France was engaged with Spain in the Valtelline, there were Protestant risings at La Rochelle, and in the Cevennes. Richelieu was not strong enough to deal with two enemies at once, and came to terms. Two years later La Rochelle rose again, first helped and then abandoned by the incompetent Buckingham. It was a very strong place, with a population of 40,000 and a tradition of independence—the chief symbol of political Huguenotism. Richelieu determined to make an example of it. After nearly a year’s siege, the repulse of two English fleets, and the death of 15,000 of its inhabitants, the city surrendered. Richelieu allowed no reprisals, but pulled down every stone of the fortifications. With them fell the resistance of the Huguenots. Next year was published the Grace of Alais—not a treaty such as had previously been made between the Catholics and the Protestants, but a concession on the part of the crown to its rebellious subjects. It left the Huguenots their liberty of worship, and their rights as citizens; but it took away from them their synods and their fortified cities. No doubt this left them more than ever at the mercy of the Catholics. Richelieu might claim that he was tolerant; but by withdrawing the political safeguards of toleration he prepared the way for Louis XIV’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes. At the moment, however, and for his immediate purpose of national unity, the policy was effective. Richelieu had no further trouble with the Protestants. And it was noticed that, when the disorders of the Fronde broke out twenty years later, the Huguenots took no part in them.

Next the nobles. This was a longer struggle, and Richelieu’s success was less final. He had to deal, not with an organized party, but with a series of plots. The centre of trouble was not in distant provinces, but in Paris, and at Court. Restive or ambitious nobles found support in Gaston of Orleans, the King’s brother, who, until the birth of Louis XIV in 1638, was heir to the throne; in the Spanish party round the Queen, Anne of Austria; and in Mary de Medici, the Queen-mother, who could never forgive Richelieu for superseding her in the government of the country. Mme. de Stael says that the French are born revolutionaries, but bad plotters. Certainly every intrigue against Richelieu was a complete failure. The Cardinal’s spies kept him well informed; and once a plotter was convicted, no rank or favour availed to save him from the King’s gaoler, or the King’s executioner. Forty-seven sentences of death for high political offences were passed during Richelieu’s Ministry, and twenty-six of them were carried out. The victims included five Dukes, four Counts, a Marshal of France, and the King’s special favourite, Cinq Mars. The King’s brother could not be punished. But he could be frightened. Almost the only extant sermon of Richelieu’s, preached to the Court before the trial of a disloyal noble against whom Gaston had turned King’s evidence, is an attempt to put the fear of Hell into his soul. It is eloquent enough; but the Cardinal must have felt handicapped by having to use such uncongenial methods.

Whilst disloyal nobles lost their liberty, or their lives, even loyal nobles might lose their homes. Castles, except where they were needed for the defence of the frontiers, were systematically pulled down. Duelling, one of the curses of the times, was forbidden, and rigorously punished. In every way the nobles were made to feel that there was only one power in the land, and that the King’s. It is impossible to feel much sympathy for them. Some were plotting against the government, and in face of a foreign enemy. Many more valued their class privileges above their duty to the country. But there is generally something wrong with the government of a state, as there is in the management of a school, or in the discipline of a regiment, when punishments are numerous or excessive. The despotism’ of Cardinal Richelieu may not have ‘entirely destroyed the originality of the French character – its loyalty, its frankness, its independence’ [de Stael]; but it did much to destroy the political usefulness of the class which should have been the chief support of the Crown, and so to leave the monarchy isolated in face of a disfranchised and discontented middle class. As Richelieu’s treatment of the Huguenots pointed to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, so his treatment of the nobility led to the troubles of the Fronde, and prepared the way for the Revolution. At the moment it added another figure to his score of unpopularity. When he died, someone wrote this ironical epitaph for him:—

KIND RICHELIEU’S BODY HERE DOTH LIE,

WHO NEVER HURT A SINGLE FLY—

A VERY JUST AND PEACEFUL FELLOW:

AS FOR HIS SOUL, IF GOD NO BETTER

FORGIVES THAN HE FORGAVE HIS DEBTOR,

I RATHER FEAR IT’S GONE TO HELL, OH!

[Roca].

VII

Something remains to be said about other sides of Richelieu’s home government. One of his first needs was an army and a navy. His ‘Ordonnance’ of 1619 set the pattern which, in many respects, the French army followed for a hundred years. When Louis XIII came to the throne he had 10,000 men; when he died, 164,000. A navy was created out of nothing. In 1626 it was necessary to borrow Dutch ships for the siege of La Rochelle. In 1642 there were two French fleets at sea, numbering eighty sail. Richelieu was one of the first modern statesmen to realise the importance of sea power. We have seen it in his Memorandum of 1624. We see it again in a paper published among his letters, in which he describes with great indignation how, when Sully sailed as ambassador to England, he was summoned to dip his flag to an English vessel in the Channel, and how, when he refused, the British skipper fired three shots, which ‘pierced the hull of his ship, and the hearts of all good Frenchmen,’ and compelled him to acknowledge our supremacy at sea [Avenel].

Richelieu gave the French monarchy a new impulse, but no new ideas. The traditional government by the King and the King’s friends was now represented by the King, the King’s Ministers, and the King’s Council—the Conseil du Roi, or d’Etat. This last sat for different kinds of business—provincial, financial, legal, and so on—on different days; the Secretaries of State, who had been merely the Clerks of the Council, were beginning to became departmental ministers. But they had as yet no independent responsibility, and Richelieu was careful to keep foreign diplomacy in his own hands.

In the government of the provinces increasing use was made of the Intendants, who, since the time of Francis I, had occasionally been employed to supersede the seigneurs. They were given summary jurisdiction, and executive authority in matters of police and finance. Nothing did more to centralize the government of France: but nothing did less to create (what was more needed) national French feeling. Meanwhile, the natural organs of public opinion—the provincial Estates—were discouraged almost out of existence; and the one body representing the nation, the one constitutional check on the power of the Crown—the Estates General—was never allowed to meet. Richelieu thought himself better acquainted than they were with what France needed, and better able to carry it out alone. But by not consulting the people he rendered it unfit to be consulted. By being so strong himself he made his successors too weak. Richelieu created the French monarchy: the French nation was the work of the Revolution.

In financial administration Sully’s good tradition was not preserved. The expenditure during Richelieu’s ministry was more than quadrupled, and the taxes proportionately increased. The peasantry, forced to pay five times as much ‘taille’ as before, fell into a terrible state of poverty. But little more than 50 per cent. of what was extorted reached the Treasury. Too much was embezzled, too much went in expenses of collection, too much was diverted for local expenditure. To raise more money, offices were sold wholesale: but out of the 500 million livres so raised, 150 millions could not be accounted for. There were peasant risings in 1634 and 1639, and the cruelty with which they were put down made Richelieu as much hated by the country population as he was by the Huguenots or by the nobility.

VIII

You may wonder how it was that, in face of such difficulties, the Cardinal could carry on. The answer lies partly in his army and in his spies, partly in the success of his foreign policy; but mostly in the support given him by the King. Richelieu’s enemies said that he terrorized Louis; that he exaggerated the dangers of rebellion, in order to make the King dependent on him; and that during his last illness Louis was heard to declare that the Cardinal had been the death of him. It was at least commonly supposed that the roles of Minister and King were reversed. A popular epitaph on Louis ran:

THIS KING WAS VALET TO A PRIEST,

AND PLAYED HIS PART WITHOUT DISASTER;

HE’D ALL THE VIRTUES OF A MAN,

BUT NEVER ONE THAT FITS A MASTER.

[Roca].

But Louis was in fact more than a brave man and a good soldier: he was a sensible, hard-working sovereign, and jealous of his authority. He generally left matters of policy to Richelieu; but insisted on being kept informed of what was done: and when he took the initiative, as he often did, in military affairs, he expected Richelieu to carry out his orders. The Cardinal himself once said that it was more difficult to conquer the four foot square of the King’s study than all the battlefields of Europe’ [Malet]. Louis, for his part, admired his Minister, defended him against every attack, and carried on his policy during the short time that he outlived his death. It was a real partnership, and I think that Louis’ share in it has been understated. He was not a King who naturally caught attention. In character more English than French, he had neither the geniality of Henry IV nor the grand manner of Louis XIV. His reputation has suffered both from Richelieu’s unpopularity among the memoir-writers of his own day, and from his popularity with the historians of later times [cf. Topin].

Of Richelieu himself we may say what Wellington said of Napoleon, that he was not a man but a principle. His virtues were dedicated to the service of the State: his crimes, he would have urged, were excused by it. His two great designs—the unity of his country at home, and its supremacy abroad—if not (as Cardinal de Retz suggested) as great as those of Caesar or Alexander, were sufficiently ambitious; and their success created the France of Louis XIV—a society which set the fashion to all Europe, and a government which was the last word in unenlightened despotism. We shall soon see the limitations of that society, and the disasters to which that government led. We may blame Richelieu for not trusting the nation more, for not educating it in self-government. But we can hardly blame him for not being a prophet. He achieved the most that is generally asked of a statesman—a policy suited to the nation as he knew it, and the power to carry it out. With that, he was no self-seeker, but a genuine patriot. It is said that on his death-bed he refused to be spared the questions from which high ecclesiastics were usually exempt. “Treat me,’ he said to his confessor, as an ordinary Christian.’ ‘Well then, do you believe the articles of the Faith?’ ‘Absolutely; and I would that God would grant me a thousand lives, so that I might give them all to the Faith and to the Church.’ ‘Do you forgive your enemies?’ ‘With all my heart; and I pray God to punish me if I have ever had any other intention than the good of the State and of the Church’ [Topin].

“He believed in France, he believed in the Monarchy, and he believed in the Church as the support of the Throne. ”

Richelieu made mistakes in pursuit of his principles, but his mark is still felt today. Would all great and influential statesmen hold to loft principles as Richelieu, come hell or high water, instead of our constant wheel of venal grifters and of mean spirit.