Editor’s note: The following — a British perspective on the American Revolution — is extracted from The United States: An Outline of Political History, by Goldwin Smith (published 1893).

(Continued from Part 4)

It was in the dark hour before the arrival of French aid that treason entered into the heart of Benedict Arnold, the commander of the all-important lines upon the Hudson. Arnold had been one of the best of the American commanders, perhaps the most daring of them all. He had reason to complain of slights and wrongs, not at the hands of Washington who valued and trusted him, but at the hands of the politicians. He seems to have despaired of the revolutionary cause and to have shrunk from the French alliance, suspecting as did others that the French had designs on Canada, and to have made up his mind to play Monk. He opened clandestine negotiations with Clinton, whose adjutant and envoy was the ill-starred André, a young man of culture and sensibility. By Arnold’s invitation André visited the American lines, and on his way back fell into the hands of the enemy while Arnold had just time to escape. Whether having been drawn into the American lines by their commander he was guilty of having acted as a spy must be decided by martial law, which has rules and a phraseology of its own. But it can hardly be said that he was tried. He was convicted and sentenced solely on his own statement, of which the incriminating part was taken, while to the exculpating part, his averment that he had been unwittingly drawn by Arnold within the lines, no weight was allowed, though the evidence for both was the same. Greene, who presided over the court, had written before the trial: “I wrote you a letter by the post yesterday respecting General Arnold. Since writing that letter General Washington is arrived in camp and the British Adjutant General and Joshua Smith, both of whom are kept under strong guard. They are to be tried this day and doubtless will be hung to-morrow.” It seems vain to cite the foreign officers who sat in the court of inquiry as impartial judges; they were enemies of England and of Englishmen. André was hanged with great parade, his prayer that he might be shot having been refused by Washington, and as his enemies denied him a soldier’s death his country did right in giving him more than a soldier’s tomb. It seems certainly to have been hinted to Sir Henry Clinton that André might be exchanged for Arnold. If the hint came from any important quarter a dark shade is cast upon the execution of André.

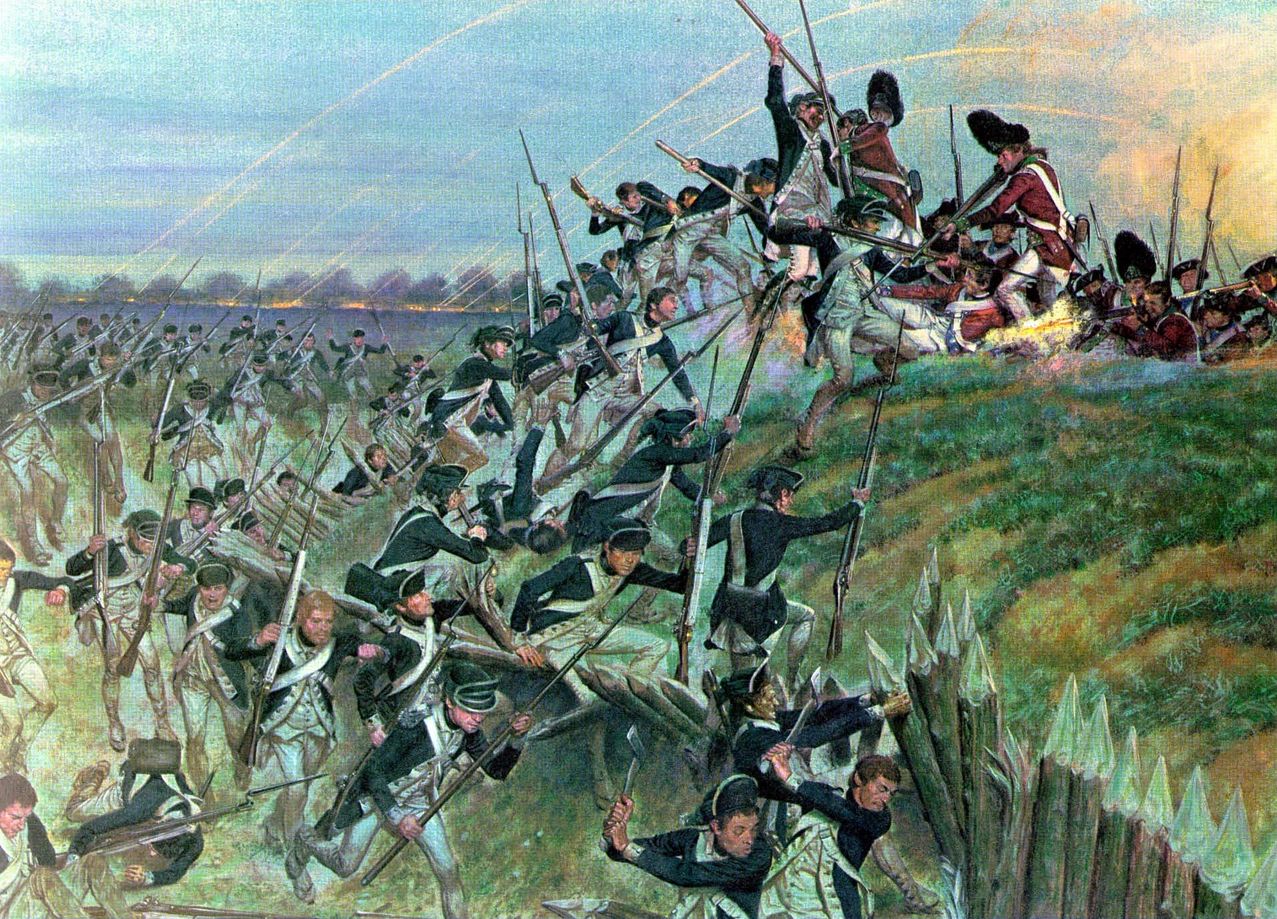

After Burgoyne’s disaster and the proof which the Northern States had on that occasion given of their spirit, the royal commanders turned to the South, which they might hope to detach and save for the king, even if the North was lost. In the South there was reason to believe that Royalism was stronger than in the North. The people were not Puritan, they were more monarchical than those of New England, more simple-minded, and being not traders or manufacturers but husbandmen, they had been less galled by the laws of trade. Clinton took Charleston, the chief southern port and city, with a large garrison and great stores. Cornwallis, left in command while Clinton returned to New York, gained an easy and complete victory over very superior numbers at Camden in South Carolina, the militia giving signal proof of the truth of Washington’s saying that they would not stand against regulars in the open field. He afterwards gained a victory less easy or complete over Greene, the best of the American generals save Washington, at Guildford. Tarleton, a local royalist, also did wonders with his light horsemen, though he soon found his match in the American Marion. But Tarleton, with a detachment of Cornwallis’ force under his command, attacking in his overconfidence with weary troops, was defeated at the Cowpens; the only battle, if an engagement on so small a scale can be called a battle, lost in open field by the king’s troops during the war. The local loyalism, though fiery and too often cruel, proved not staunch, and the effect of the incursion was rather to let loose mutual massacre and plunder amongst the motley population of Dutch, Germans, Quakers, Irish Presbyterians, and Scotch Highlanders, than to bring the colonies back to their allegiance. A combined French and American attack on New York appearing imminent, Cornwallis, recalled by Clinton, fell back into Virginia and intrenched himself on a neck of land at Yorktown on the Chesapeake Bay, in a position which so long as his own fleet commanded the bay was a stronghold, but when the command of the sea was lost became a trap. The command of the sea was lost by the arrival of a French fleet under De Grasse, with which there was no British fleet to cope. Washington uniting his army to that of Rochambeau, they moved together on Yorktown, while some misunderstanding, as it appears, between Cornwallis and Clinton retarded Clinton’s aid. Cornwallis, in a desperate position and beleaguered by an army four times outnumbering his effective force, after turning his eyes for some days to the sea in the vain hope of discerning British sails, was compelled to capitulate and march out, as the painting in the hall of the Capitol depicts him, between the lines of French and American troops. Washington had the modesty and generosity to keep off spectators. This was the end. It would not have been the end if America had been a foreign enemy and the heart of the British nation had been really in the struggle. It was not the end of the contest with France, Spain, and Holland. But of the contest with the colonies it was the end. The American farmers might go home, hang up their muskets and follow the plough as they had in “the old colony days,” which probably not one in a hundred of them regarded with abhorrence and to which most of them, we may be pretty sure, had been looking back with regret. No conflict in history has made more noise than the Revolutionary War. It set flowing on every fourth of July a copious stream of panegyrical rhetoric which has only just begun to subside. Everything connected with it has been the object of a fond exaggeration. Skirmishes have been magnified into battles and every leader has been exalted into a hero. Yet the action and, with one grand exception, the actors were less than heroic, the ultimate conclusion was foregone, and the victory after all was due not to native valour but to foreign aid.

Civil war as well as international war there will sometimes be, but it ought always to be closed by amnesty. For amnesty Cromwell declared on the morrow of Worcester. Amnesty followed the second civil war in America. The first civil war was followed not by amnesty, but by an outpouring of the vengeance of the victors upon the fallen. Some royalists were put to death. Many others were despoiled of all they had and driven from their country. Several thousands left New York when it was evacuated by the king’s troops. Those who remained underwent virulent persecution. Massachusetts banished by name three hundred and eight of her people, making death the penalty for a second return; New Hampshire proscribed seventy-six; Pennsylvania attainted nearly five hundred; Delaware confiscated the property of forty-six; North Carolina of sixty-five and of four mercantile firms; Georgia also passed an act of confiscation; that of Maryland was still more sweeping. South Carolina divided the loyalists into four classes inflicting a different punishment upon each. Of fifty-nine persons attainted by New York three were married women, guilty probably of nothing but adhering to their husbands, and members of the council or law officers who were bound in personal honour to be faithful to the crown. Upon the evacuation of Charleston, as a British officer who was upon the spot stated, the loyalists were imprisoned, whipped, tarred and feathered, dragged through horse ponds, and carried about the town. with “Tory” on their breasts. All of them were turned out of their houses and plundered, twenty-four of them were hanged upon a gallows facing the quay in sight of the British fleet with the army and refugees on board. Such was the statement of a British officer who was upon the spot, ashore and an eye witness to the whole. Some of these men, such as Johnson the guerrilla leader and Butler the author of the attack on Wyoming, had been guilty of crimes for which they might justly have suffered under the common law, though they could not have suffered more justly than some ruffians on the other side. But the mass had been guilty of nothing but fidelity to a lost cause. Honour, we will say with Mr. Sabine, to those who protested; to General Greene, who said that it would be “the excess of intolerance to persecute men for opinions which twenty years before had been the universal belief of every class of society”; to Alexander Hamilton, who nobly stood up against the torrent of hatred as the advocate of its victims in New York; to John Jay, who said that he “had no desire to conceal the opinion that to involve the Tories in indiscriminate punishment and ruin would be an instance of unnecessary rigour and unmanly revenge without a parallel except in the annals of religious rage in the time of bigotry and blindness.” The loyalist exiles peopled Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Upper Canada with enemies of the new Republic, and if a power hostile to the Republic should ever be formed under European influence in the north of the continent, the Americans will owe it to their ancestors who refused amnesty to the vanquished in civil war.

By the treaty of peace, Great Britain not only recognized the independence of her colonies but gave them, what France was not very willing and Spain was very unwilling to give, unlimited extension to the westward over the territory which her arms had won from France. Canada, her bond of honour to the loyalists compelled her to retain. In the course of the negotiations the hollowness of the league of hatred between America and the European enemies of England appeared. France, as the American envoys thought, played America false, and the Americans were guilty towards France of what they admitted to be a breach of diplomatic courtesy while France called it by a harder name. “It is now substantially proved,” says a recent American writer of eminence, “that the unmixed motive of the French cabinet in secretly encouraging the revolted colonies, before open war had broken out between France and England, had been only to weaken the power and sap the permanent resources of the natural and apparently eternal enemy of France.” To seize the opportunity of crippling a powerful enemy was the avowed aim of Vergennes in urging his king to go to war. The conduct of negotiations on the British part fell at first to the lot of Shelburne, the most liberal statesman of his day, who had ardently desired re-union and who now, with young Pittby his side, sought to make the settlement with the colonies a treaty not of peace only but of reconciliation, dividing the imperial heritage without destroying the moral unity of the race. Had Shelburne’s policy prevailed, there would have been no war of 1812, there would have been no fisheries question, nor Behring Sea controversy. But Shelburne’s government was overthrown by the factious ambition of Fox, with whom it is painful to say went Burke. A demand for compensation to the loyalists Congress, unable to deny its justice, put off with an ironical recommendation of compliance to the States, whose resolution it knew. England gave the loyalists more than three millions and a half sterling if we include the pensions and half pay, and new homes to those that chose them under her flag. The recognition of private debts was, thanks to the honesty and wisdom of John Adams, though not without great difficulty, obtained.

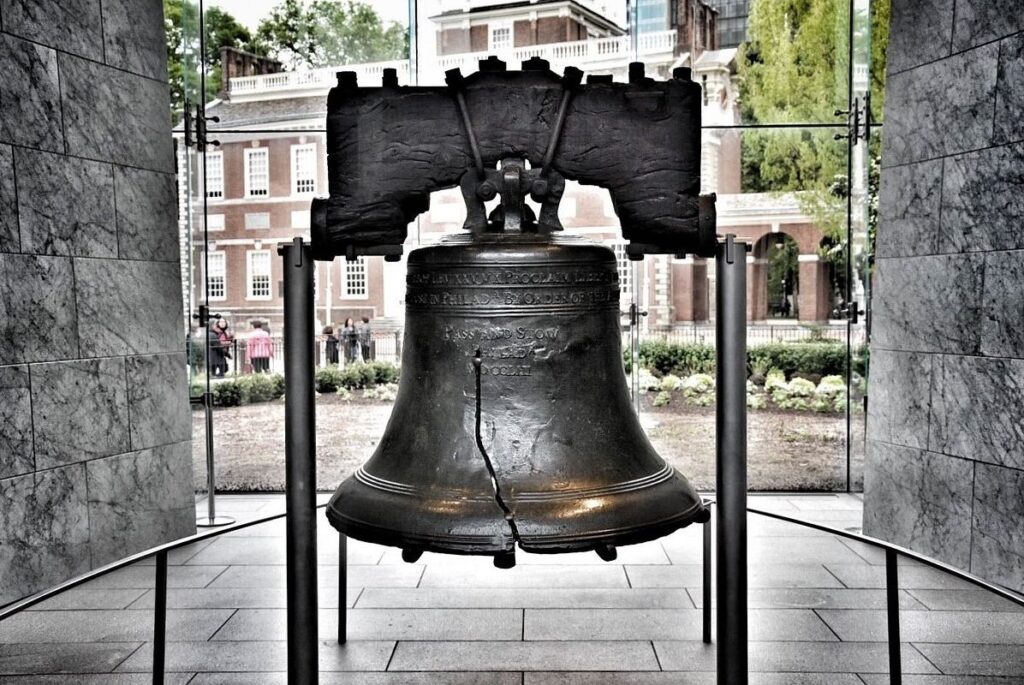

The political separation of the colonies from the mother country, once more, was inevitable. Not even the most fervid imperialist can imagine the sixty-five millions of the United States remaining dependent on the thirty-five millions of the British Islands. No English statesman in the present day could think without shuddering of such a task as that of governing New England across the Atlantic. But by right-minded men the violence of the separation must ever be deplored. The least part of the evil was the material havoc. Of this the larger share fell as usual upon the country which was the scene of war. England came out at last with her glory little tarnished. She had yielded not to America, but to America, France, Spain, and Holland combined. That tremendous coalition she had faced, the national spirit of her people which had not been thoroughly awakened by the war against her own colonists, rising to do battle with her foreign enemies; and her flag floated in its pride once more over the waters which were the scene of Rodney’s victory, and on that unconquered rock beneath which the Spaniard received his share of the profits of the league. While she was losing nominal empire in America, illustrious adventurers had enlarged her real empire in Hindustan. Of all the consequences, the worst to Great Britain was that the oligarchy which ruled in Ireland was enabled, by taking advantage of her peril, for a time to cast off imperial control and to set up an independence which ended in the catastrophe of ’98. The loss of her colonial dependencies in itself was clear gain, political, military, and commercial. Their trade, her share of it, and her profit from it, increased after their political emancipation. She was thus repaid what she had expended in the war. But she lost what was more valuable than glory, empire, or the profits of trade, the love of her colonists, and in place of it incurred their intense and enduring, though unreasonable and unworthy, hatred. The colonists by their emancipation won commercial as well as fiscal freedom, and the still more precious freedom of development, political, social, and spiritual. They were fairly launched on the course of their own destiny, which diverged widely from that of a monarchical and aristocratic realm of the old world. But their liberty was baptized in civil blood, it was cradled in confiscation and massacre, its natal hour was the hour of exile for thousands of worthy citizens whose conservatism, though its ascendancy was not desirable, might as all true liberals will allow have usefully leavened the republican mass. A fallacious ideal of political character was set up. Patriotism was identified with rebellion, and the young republic received a revolutionary bias, of the opposite of which it stood in need. The sequel of the Boston Tea Party was the firing on Fort Sumter.

Another consequence was the severance of Canada from the United States and a schism of the English-speaking race on the North American continent, opening the way, which unity would have closed, for the introduction of international enmities, of a balance of power, and of war. Statesmanship is now labouring against an accumulation of difficulties to undo the evil work done a century ago by denial of amnesty to the vanquished in civil strife.

France in gratifying her hatred of England became bankrupt. Bankruptcy brought revolution, and the French revolution brought a deluge of woe, not only on France but on mankind. Up to that time the spirit of philosophy, philanthropy, and reform had by a peaceful movement been gaining possession of the governments of Europe. An era of improvement without convulsions seemed to be dawning. Young Pitt when he came into power saw nothing before him but peace and reduction of taxes. He looked forward to the total abolition of customs and to free trade, within sight of which the world has never since come. The American revolution by the financial ruin which it brought on France, by the revolutionary spirit which it infused into her, and by the violence for which it gave the signal, changed the scene, and Jacobinism, terrorism, reactionary despotism, militarism, incarnations of the same malignant spirit, were let loose upon a world which they still distract and ravage. Misfortune pursued even the persons of those most concerned. The French king, whose weakness had consented to the war, and his queen, whose folly had encouraged it, mounted the scaffold before the unpitying eyes if not amid the plaudits of the American democracy which they had saved. D’Estaing having helped the queen to her doom, himself followed her, and Lafayette, after dancing for a moment on the top of the revolutionary wave, was overturned by genuine revolutionists and flung out into disappointment and impotence.

(Continued in Part 6)