Editor’s note: The following — a British perspective on the American Revolution — is extracted from The United States: An Outline of Political History, by Goldwin Smith (published 1893).

(Continued from Part 3)

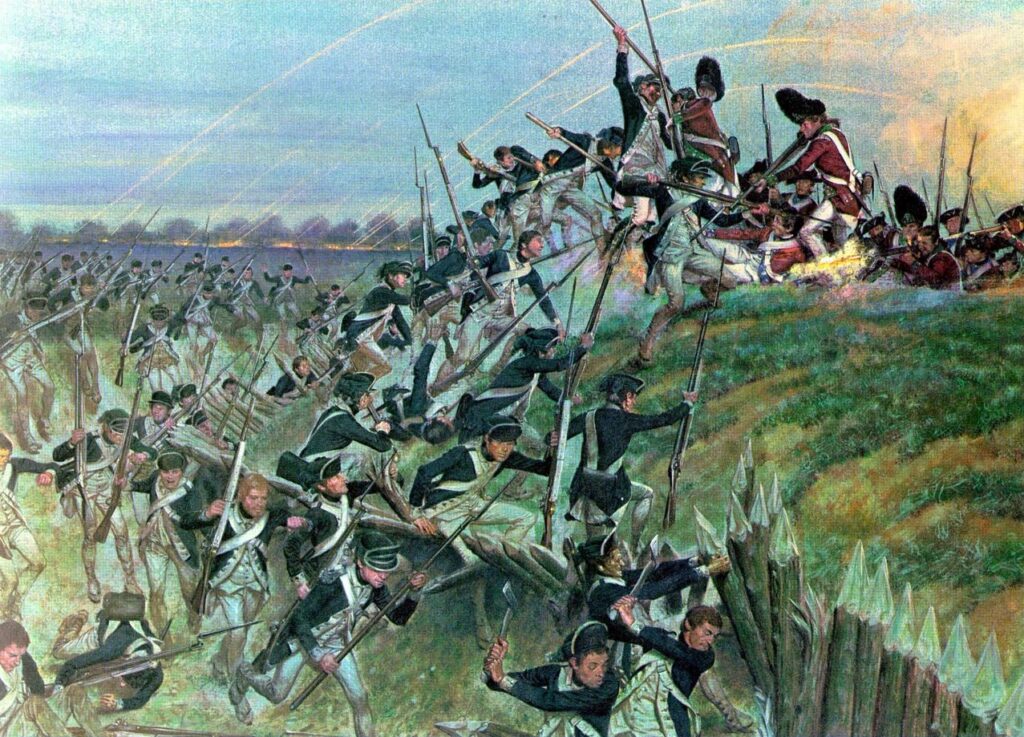

The Netherlands, when they rose against Spain and the Inquisition, had a cause terribly great and showed spirit as great as their cause. The cause in which the Americans rose against the imperial government was not so great if it was not largely rhetorical, and the amount of spirit which they showed was proportional. When from drinking patriotic toasts, declaiming against tyranny, tarring and feathering Tories, and hanging stamp collectors in effigy, it came to paying war contributions and facing the shot, enthusiasm declined. Of this Washington became sensible as soon as he had assumed the command. From the lines before Boston, 28th November, 1775, he writes: “Such a dearth of public spirit and such want of virtue, such stock-jobbing and fertility in all the low arts to obtain advantages of one kind or another, in this great change of military arrangement, I never saw before, and pray God’s mercy that I may never be witness to again.” This wail runs through his letters, growing more and more mournful to the end of the war, or at least till the arrival of French aid. From Valley Forge in he writes: “Men are naturally fond of peace, and there are symptoms that may authorize an opinion that the people of America are pretty generally weary of the present war. It is doubtful whether many of our friends might not incline to an accommodation on the grounds held out, or which may be, rather than persevere in a contest for independence.” From Philadelphia, 30th December, 1778, he writes: “If I were called upon to draw a picture of the times and of men from what I have seen, heard and in part know, I should in one word say that idleness, dissipation, and extravagance seem to have laid fast hold of most of them; that speculation, peculation, and an insatiable thirst for riches seem to have got the better of every other consideration, and almost of every order of men; that party disputes and personal quarrels are the great business of the day; while the momentous concerns of the empire, a great and accumulating debt, ruined finances, depreciated money, and want of credit which in its consequences is the want of everything, are but secondary considerations and postponed from day to day, from week to week, as if our affairs wore the most promising aspect.” John Adams had oratorically decreed that the war should be violent and short, but oratory does not shorten war or make anything violent but passion. The eloquent opponents of the tea duty did not, like the opponent of ship-money, take the field. They were content with the part, to use a phrase adopted by Washington, of chimney corner heroes. If John Adams could sigh as he said he did for things as they had been before the war, the people were not likely to feel that the change was worth much of their money or their blood. When the war came their way they would readily turn out, and fight well in their own sharp-shooting fashion in defence of their own states, but they would not readily turn out in the Continental cause even though the assembly of Virginia might offer to any patriot who would take arms to deliver the country from slavery three hundred acres of land and a healthy sound negro. If they did turn out it was for a fixed term, and at the end of that term they insisted upon taking their departure, notwithstanding it might be the eve of a battle, carrying with them their arms and ammunition, not assuredly because they lacked courage, but because they lacked zeal in the cause. “Soldiers absent themselves from their duty in numbers, staying at their homes, sometimes in the employment of their officers; drawing pay, while they are working on their own plantations or for hire.” The troops of Connecticut at one time were mostly on furlough, and Washington finds such a mercenary spirit pervading them that he could not be surprised at any disaster. Regiments are expected in vain, harvest and a thousand other excuses being given for delay. At a critical moment a militia is reduced from six thousand to less than two thousand. It takes all the exertion of the officers to induce a corps to stay six weeks on a bounty of ten dollars. Washington’s army in short is always moulting; there is not time to drill the men before they are gone, and discipline is impossible because if it was enforced they would go. Washington complains also of the want of patriotic feeling among the people. The conduct of the Jerseys, he says, “is most infamous; instead of aiding him they are making their submission as fast as they can. Pennsylvanian militiamen, instead of responding to the summons of the Council of Safety, exult at the approach of the enemy and over the misfortunes of their own friends. The disaffection of Pennsylvania is beyond conception. The people bring supplies as readily to the royal army as to their own; more readily in fact, since the royal army pays not in paper but cash.” Officers appropriate the money for the payment of the troops. Cabals and intrigues about appointments, jealousies between soldiers from different states, selfish interests of all kinds are stronger than adherence to the cause. There was the pride too, though Washington does not mention it, of the Virginian gentlemen who looked down on the New England trader not less than the officers of the royal army had looked down on those of the colonial militia. All this goes far towards justifying the king’s judgment and that of his informants as to the strength of the resistance and the chances of the war. The army, Washington says, was at one time losing more by desertion than it gained by recruiting. Deserters, defaulters, and malingerers, of whom there were also plenty, had every excuse that the failure of the commissariat and the arsenals could give. Two thousand men at one time were without firelocks, and the supplies of food and clothing seem to have been always most defective. That his men should be starving, shivering, and marking their marches over the snow with their blood, while forestallers, regraters, and monopolists are flourishing, stings Washington to the soul. The end of the dealings of Congress with the army was that the army became a skeleton, and there was at last a mutiny of the Pennsylvanian militia which was prevented from being fatal only by the personal ascendancy of the general. A sufficient force of regular troops, serving for adequate pay and pensions, was Washington’s constant desire. Cromwell’s insight taught him, after Edgehill, that instead of men serving only for pay he must form an army of men whose hearts were in the cause. Washington’s insight after a few months of command taught him that when enthusiasm had grown cold an army must be formed of men serving for good pay. “When men,” he says, “are irritated and passion inflamed they fly hastily and cheerfully to arms; but after the first emotions. are over to expect the bulk of an army to be influenced by anything but self-interest is to look for what never did happen.” Cromwell and Washington alike recognized the supremacy of discipline. “To lean on the militia,” says Washington, “is to lean on a broken reed. Being familiar with the use of the musket they will fight under cover, but they will not attack or stand in the open field.”

States refused to tax themselves and Congress had no power to tax them. Its war budget was one of confiscations, forced requisitions, and paper money. From the printing press, its mint, issued ever increasing volumes of paper currency, the value of which as usual rapidly declined, and all the faster the more Congress and its partisans, like the French Jacobins after them, had recourse to violence to make bad money pass for good. A hotel bill of seven hundred pounds was paid with three pounds cash. The phrase came into vogue, “Not worth a continental.” At last, as Washington said, there was almost a stagnation of purchase. There could not fail to ensue a fearful disturbance of commerce and of commercial morality. Debts contracted in good money were paid in worthless paper. Washington was himself thus defrauded while he was serving the country without pay, a wrong of which he speaks with his usual magnanimity. Gambling and speculation naturally followed. Fortunes were made by knaves and riotous living went on while the army suffered and dwindled to a shadow. Years afterwards Tom Paine, no straight-laced economist, seriously demanded that any one who proposed to return to paper money should be punished with death. The inestimable clause in the American constitution forbidding legislation which would impair the faith of contracts, may perhaps be regarded in part as a memorial of those evil times.

A fleet, Congress can scarcely be said to have had. But what local assistance, independently of the armies of the central government, did on land, privateers manned by the hardy seamen of New England did at sea. A number of English merchantmen were captured in American waters, and Paul Jones in his Bonhomme Richard made himself the terror of the English coasts. The royal navy however presently asserted its superior power, and American commerce was swept from the sea.

The surrender of Burgoyne proved decisive, as it brought France to the aid of the Americans. Ever since her loss of Canada she had been intriguing through her agents in the colonies. From the outset of the war she had been sending secret aid to the revolutionists, and lying when expostulations were addressed to her. The motive of her government was enmity to England. But there was a section of her aristocracy which had embraced political reform and even begun to dally with revolution, a pastime for which the salons afterwards paid dear. A youthful scion of this section, Lafayette, fired at the sight of American revolt, had gone forth on a republican crusade and become the companion in arms of Washington. After Burgoyne’s surrender American envoys were able to persuade the French government to make a treaty with the colonies and go to war with Great Britain, from whom France had received not the slightest provocation. Spain was afterwards drawn in, not by sympathy with the Americans whom she regarded as dangerous neighbours to her American dependencies, but by the hope of recovering Gibraltar; Holland by maritime jealousies and disputes. Thus England, in addition to her revolted colonists, had the greatest military power in Europe and the three greatest naval powers on her hands. She lost that command of the sea which had enabled her to crush the commerce of the colonists, to wear them out by pressure on the seaboard, and to choose her own point of attack. On the other hand her national spirit was aroused to do battle with her ancient foe. Chatham would have dropped the colonies and turned on France. Lord North, being no Chatham, sent out commissioners with overtures of reconciliation, offering the colonies representation in Parliament. Of course his attempt proved worse than vain. A great French fleet under d’Estaing soon appeared on the scene. A French army was to follow, and the French treasury supplied Congress with the hard cash of which it was by this time in the sorest need. Incompatibilities and misunderstandings between the French and their colonial allies put off the catastrophe, but the balance was decisively turned and the result was no longer in doubt. “To me,” said Washington, August 20th, 1780, “it will appear miraculous if our affairs can maintain themselves much longer.” “If,” he added, “the temper and resources of the country will not admit of alteration, we may be reduced to seeing the cause in America upheld by foreign arms.” That time had now come.

(Continued in Part 5)