Editor’s note: Here follow Chapters 40 through 45 of My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, by General Ben Viljoen (published 1902). All spelling in the original.

(Continued from Part 6)

CHAPTER XL

CAPTURING A FREEBOOTER’S LAIR.

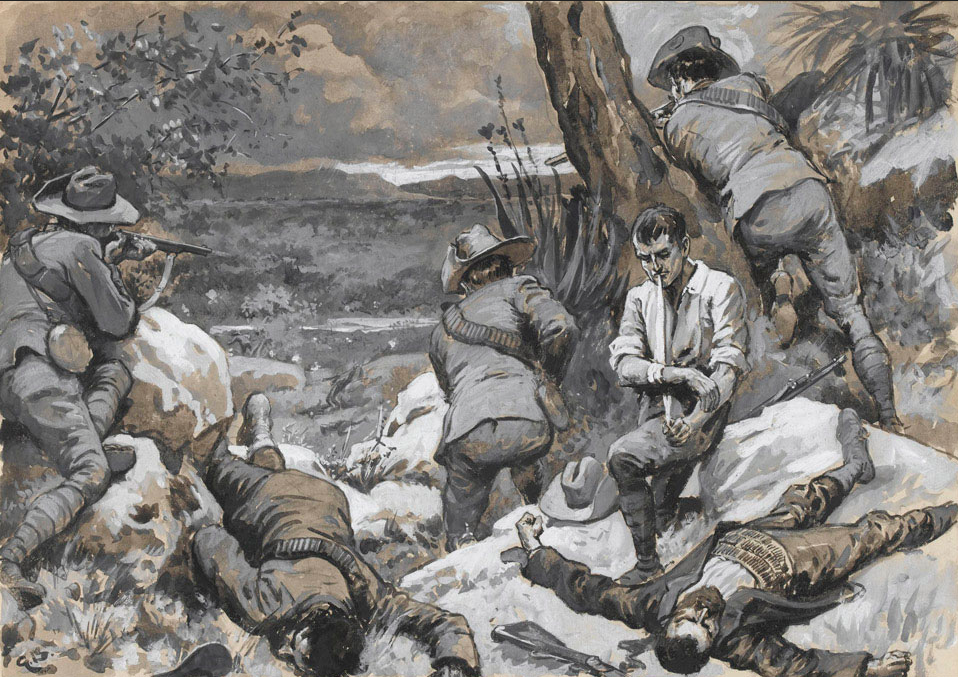

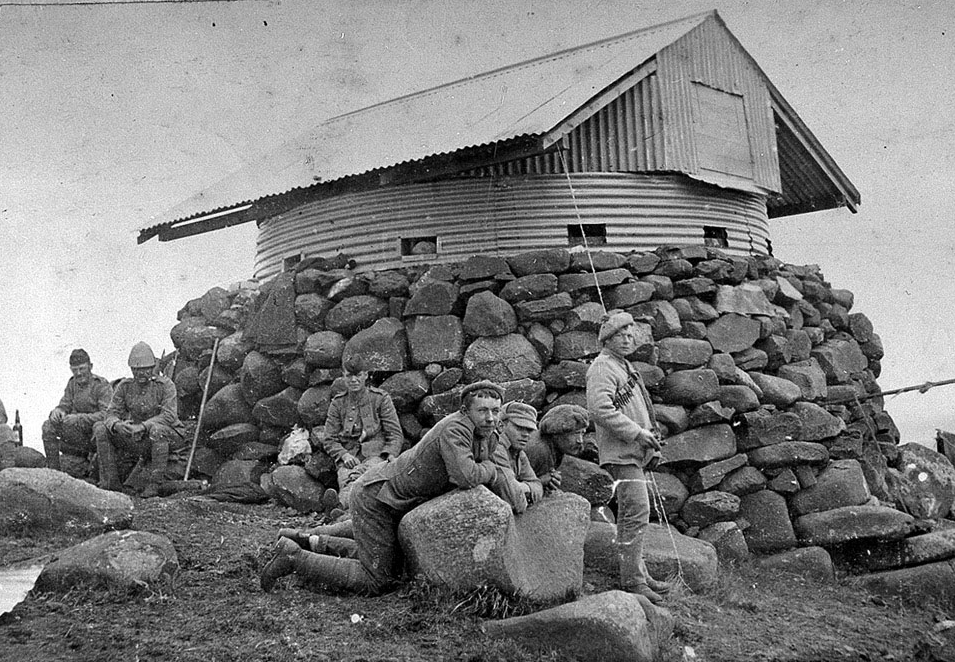

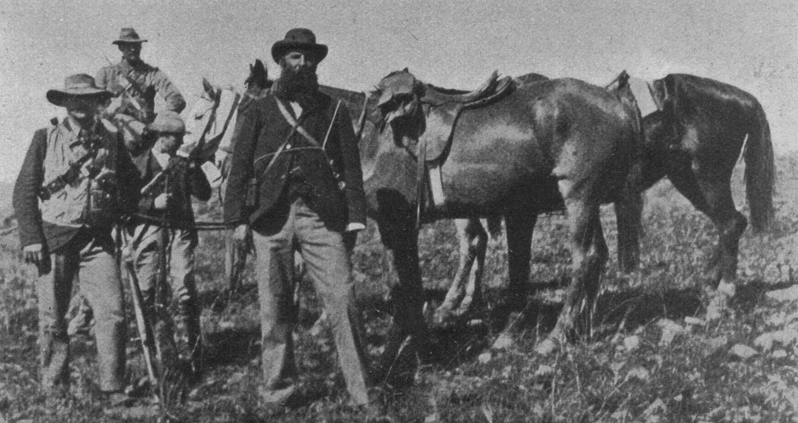

Early in the morning of the 6th of August, as the breaking dawn was tinting the tops of the Lebombo Mountains with its purple dye and the first rays of the rising sun shed its golden rays over the sombre bushveldt, the commando under Commandants Moll and Schoeman were slowly approaching the dreaded M’pisana’s fort. When within a few hundred paces of it they left the horses behind and slowly crept up to it in scattered order; for as none of us knew the arrangement or construction of the place, it had been arranged to advance very cautiously and to charge suddenly on the blowing of a whistle. Nothing was stirring in the fort as we approached, and we began to think that the garrison had departed; but when barely 70 yards from it the officers noticed some forms moving about in the trenches, which encompassed it. The whistle was blown and the burghers charged, a cheer rising from a hundred throats. Volley after volley was discharged from the trenches, but our burghers rushed steadily on, jumped into the trenches themselves and drove the defenders into the fort through secret passages. The English now began firing on us through loopholes in the walls and several of our men had fallen, when Commandant Moll shouted, “Jump over the wall!” A group of burghers rushed at the 12-foot wall, and attempted to scale it; but a heavy fire was directed on them and seven burghers, including the valiant Commandant Moll, fell severely wounded. Nothing daunted, Captain Malan, who was next in command of the division, urged his men to go on, and most of them succeeded in jumping into the fort, where, after a desperate resistance, in which Captain ——, their leader, fell mortally wounded, the whole band surrendered to us. Our losses were six burghers killed, whilst Commandant Moll and 12 others were severely wounded. The burghers found one white man killed in the fort, and two wounded, whilst a score of kaffirs lay wounded and dead. We took 24 white prisoners and about 50 kaffirs. I repeat that the whites were the lowest specimens of humanity that one can possibly imagine.

Hardly was the fight over and our prisoners disarmed when a sentry we had posted on the wall called out:

“Look out, there is a kaffir commando coming!”

It was, in fact, a strong kaffir commando, headed by the chief M’pisana himself, who had come to the rescue of his friends of Steinacker’s Horse. They opened fire on us at about 100 yards, and the burghers promptly returned their greeting, bowling over a fair number of them, at which the remainder retired.

Alongside the fort were about 20 small huts, in which we found a number of kaffir girls. On being asked who they were, they repeated that they were the “missuses” of the white soldiers. Inside the captured fort we found many useful articles, and the official books of this band. They contained systematic entries of what had been plundered, looted and stolen on their marauding expeditions and showed how they had been divided amongst themselves, deducting 25 per cent. for the British Government.

A long and extensive correspondence now took place about this matter between myself and Lord Kitchener. I wished first to know whether the gang was a recognised part of the British Army, as otherwise I should have to treat them as ordinary brigands. After some delay Lord Kitchener answered that they were a part of His Majesty’s Army. I then wished to know if he would undertake to try the men for their misdeeds, but this was refused. This correspondence ultimately led to a meeting between General Bindon Blood and myself, which was held at Lydenburg on the 27th August, 1901.

The captured kaffirs were tried by court-martial and each punished according to his deserts. The 24 Englishmen were handed over to the enemy, after having given their word of honour not to return to their barbarous life. How far this promise was kept I do not know; but from the impression they made upon me I do not think they had much idea of what honour meant. The captured cattle which we had hoped to find at the fort had been sent away to Komati Poort a few days before our attack and according to their “books” it must have numbered about 4,000 heads. Another section of this notorious corps met with a like fate about this time at Bremersdorp in Swaziland. They did not there offer such a determined resistance, and the Ermelo burghers captured two good Colt-Maxims and two loads of ammunition probably intended for Swaziland natives.

CHAPTER XLI

AMBUSHING THE HUSSARS.

On August 10th, shortly after our arrival with the prisoners-of-war at Sabi, and while I was still discussing with Lord Kitchener the incident related in the previous chapter, General Muller sent word to me from Olifant’s River, where I had left him with my men, that he had been attacked by General W. Kitchener three days after I had left him. It appears that his sentries were surprised and cut off from the commandos, these being divided into different camps.

The burghers who were farthest away, the Middelburg and Johannesburg men, had, contrary to my instructions, pitched camp on the Blood River, near Rooikraal, and were suddenly and unexpectedly attacked by the enemy at about two o’clock in the afternoon, whilst their horses were grazing in the veldt. Some horses were caught in time and some burghers offered a little resistance, firing at a short range, several men being killed on both sides. The confusion, however, was indescribable, horses, cattle, burghers and soldiers being all mixed up together. A pom-pom, together with its team of mules and harness, and most of the carts and saddles, were captured by the enemy. Our officers could not induce the men to make a determined stand until they had retired to the Mazeppa Drift, on the Olifant’s River. Here General Muller arrived in the night with some reinforcements and awaited the enemy, who duly appeared next morning with a division of the 18th and 19th Hussars, and, encouraged by the previous day’s success, charged our men with a well-directed fire which wrought havoc in their ranks. The gallant Hussars were repulsed in one place, and, at another, Major Davies (or Davis) and 20 men were made prisoners. At last some guns and reinforcements reached the enemy, and our burghers wisely retired, going as far as Eland’s River, near the “Double Drifts,” where they rested.

On the third day General W. Kitchener had discovered our whereabouts, and our sentries gave us warning that the enemy was approaching through the bushes, raising great clouds of dust. While the waggons were being got ready the burghers marched out, and awaited the English in a convenient spot between two kopjes. The latter rode on unsuspectingly two by two, and when about 100 had been allowed to pass, our men rushed out, calling, “Hands up!” and, catching hold of their horses’ bridles, disarmed about 30 men. This caused an immediate panic, and most of the Hussars fled (closely pursued by our burghers, who shot 10 or 12 of them). The Hussars left behind a Colt-Maxim and a heliograph for our usage. The ground was overgrown here with a prickly, thorny bush, which made it difficult for our foes to escape, and about 20 more were overtaken and caught, several having been dragged from their horses by protruding branches, and with their face and hands badly injured by thorns, whilst their clothes were half torn off their bodies.

Meanwhile the enemy continued to fire on us whilst retreating, and thus succeeded in wounding several of their own people. This running fight lasted until late in the evening, when the burghers slackened off their pursuit and returned, their losses being only one killed, Lieut. D. Smit, of the Johannesburg Police. The enemy’s losses were considerable, although one could not estimate the exact number, as the dead were scattered over a large tract of ground and hidden amongst the bushes, rendering it difficult to find them. Weeks afterwards, when we returned over the same ground, we still found some bodies lying about the bush, and gave them decent burial.

Our burghers were now once more in possession of 100 fresh horses and saddles, whilst their pom-pom was replaced by a Colt-Maxim. General W. Kitchener now left us alone for a while, for which relief we were very thankful, and fell back on the railway line. The respite, however, was short-lived; soon fresh columns were seen coming up from Middelburg and Pretoria, and we were again attacked, some fighting taking place mostly on our old battlefields. General Muller repeatedly succeeded in tearing up the railway line and destroying trains with provisions, whilst I had the good fortune of capturing a commissariat train, near Modelane, on the Delagoa Bay line; but, as I could not remove the goods, I was forced to burn the whole lot. A train, apparently with reinforcements, was also blown up, the engine and carriages going up in the air with fine effect.

CHAPTER XLII

I TALK WITH GENERAL BLOOD.

About the end of August, 1901, I met General Sir Bindon Blood at Lydenburg by appointment. We had arranged to discuss several momentous questions there, as we made little progress by correspondence. In the first place, we accused the English of employing barbarous kaffir tribes against us; in the second place, of abusing the usage of the white flag by repeatedly sending officers through our lines with seditious proclamations which we would not recognise, and we could only obey our own Government and not theirs; in the third place, we complained of their sending our women with similar proclamations to us from the Concentration Camps and making them solemnly promise to do all that they could to induce their husbands to surrender and thus regain their liberty. This we considered was a rather mean device on the part of our powerful enemy. There was also other minor questions to discuss with regard to the Red Cross.

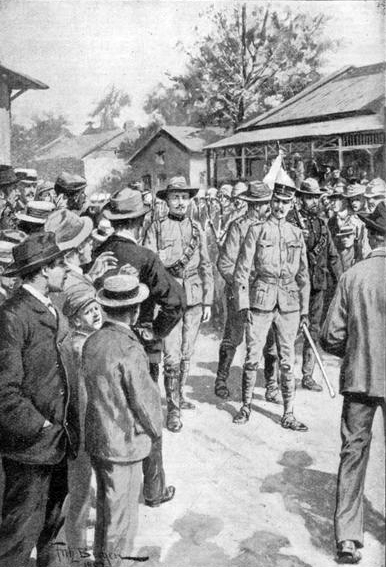

I went into the English line accompanied by my adjutants, Nel and Bedeluighuis, and my secretary, Lieutenant W. Malan. At Potloodspruit, four miles from Lydenburg, I met General Blood’s chief staff officer, who conducted us to him. At the entrance of the village a guard of honour had been placed and received us with military honours. I could not understand the meaning of all this fuss, especially as the streets through which we passed were lined with all sorts of spectators, and to my great discomfort I found myself the chief object of this interest. On every side I heard the question asked, “Which is Viljoen?” and, on my being pointed out, I often caught the disappointed answer, “Is that him?” “By Jove, he looks just like other people.” They had evidently expected to see a new specimen of mankind.

In the middle of the village we halted before a small, neat house, which I was told was General Blood’s headquarters. The General himself met us on the threshold; a well-proportioned, kindly-looking man about 50 years of age, evidently a genuine soldier and an Irishman, as I soon detected by his speech. He received us very courteously, and as I had little time at my disposal, we at once entered into our discussion. It would serve little purpose to set down all the details of our interview, especially as nothing final was decided, since whatever the General said was subject to Lord Kitchener’s approval, whilst I myself had to submit everything to my Commandant-General. General Blood promised, however, to stop sending out the women with their proclamations, and also the officers on similar missions, and the Red Cross question was also satisfactorily settled. The kaffir question, however, was left unsettled, although General Blood promised to warn the kaffir tribes round Lydenburg not to interfere in the War and not to leave the immediate vicinity of their kraals. (Only the night before two burghers named Swart had been murdered at Doorukoek by some kaffirs, who pretended to have done this by order of the English). The interview lasted about an hour, and besides us two, Colonel Curran and my secretary, Lieutenant Malan, were present. General Blood and his staff conducted us as far as Potloodspruit, where we took leave. The white flag was replaced by the rifle, and we returned to our respective duties.

CHAPTER XLIII

MRS. BOTHA’S BABY AND THE “TOMMY.”

In September, 1901, after having organized the commandos north of Lydenburg, I went back with my suite to join my burghers at Olifant’s River, which I reached at the beginning of September. The enemy had left General Muller alone after the affair with the Hussars. Reports were coming in from across the railway informing us that much fighting was going on in the Orange Free State and Cape Colony, and that the burghers were holding their own. This was very satisfactory news to us, especially as we had not received any tidings for over a month. I again sent in a report to our Commandant-General relating my adventures.

We had much difficulty in getting the necessary food for the commandos, the enemy having repeatedly crossed the country between Roos Senekal, Middelburg, and Rhenosterkop, destroying and ravaging everything. I therefore resolved to split up my forces, the corps known by the name of the “Rond Commando” taking one portion through the enemy’s lines to Pilgrimsrust, North of Lydenburg, where food was still abundant. Fighting-General Muller was left behind with the Boksburg Police and the Middelburg Commando, the Johannesburg corps going with me to Pilgrim’s Rest, where I had my temporary headquarters. We had plenty of mealies in this district and also enough cattle to kill, so that we could manage to subsist on these provisions. We had long since dispensed with tents, but the rains in the mountain regions of Pilgrim’s Rest and the Sabi had compelled us to find the burghers shelter. At the alluvial diggings at Pilgrim’s Rest we found a great quantity of galvanized iron plates and deals, which, when cut into smaller pieces, could be used for building. We found a convenient spot in the mountains between Pilgrim’s Rest and Kruger’s Post, where some hundreds of iron or zinc huts were soon erected, affording excellent cover for the burghers.

Patrols were continually sent out round Lydenburg, and whenever possible we attacked the enemy, keeping him well occupied. We succeeded in getting near his outposts from time to time and occasionally capturing some cattle. This seemed to be very galling to the English, and towards the end of September we found they were receiving reinforcements at Lydenburg. This had soon become a considerable force, in fact in November they crossed the Spekboom River in great numbers, and at Kruger’s Post came upon our outposts, when there was some fighting. The enemy did not go any further that night. The following day we had to leave these positions and the other side took them and camped there. Next day they moved along Ohrigstad River with a strong mounted force and a good many empty waggons, evidently to collect the women-folk in that place. I had to proceed by a circuitous route in order to get ahead of the enemy. The road led across a steep mountain and through thickly grown kloofs, which prevented us from reaching the enemy until they had burnt all the houses, destroyed the seed plants, and loaded the families on their carts, after which they withdrew to the camp at Kruger’s Post. We at once charged the enemy’s rearguard, and a heavy fight followed, which, however, was of short duration. The English fled, leaving some dead and wounded behind, also some dozens of helmets and “putties” which had got entangled in the trees. We also captured a waggon loaded with provisions and things that had been looted, such as women’s clothes and rugs, a case of Lee-Metford ammunition and a number of uniforms. Some days after the enemy tried to get through to Pilgrim’s Rest, but had to retire before our rifle fire. They managed, however, to get to Roosenkrans, where a fight of only some minutes ensued, when they retired to Kruger’s Post. They only stopped there for a few days, marching back to Lydenburg at night time just when we had carefully planned a night attack. We destroyed the Spekboom River bridge shortly after, thus preventing the enemy’s return from Lydenburg to Kruger’s Post in a single night. Although there is a drift through the river it cannot be passed in the dark without danger, especially with guns and carts, without which no English column will march. Every fortnight I personally proceeded with my adjutants through the enemy’s lines near Lydenburg to see how the commando in the South were getting on and to arrange matters.

The month of November, 1901, passed without any remarkable incidents. We organized some expeditions to the Delagoa Bay Railway, but without much success, and during one of these the burghers succeeded in laying a mine near Hector’s Spruit Station during the night. They were lying in ambush next day waiting for a train to come along when a “Tommy” went down the line and noticed some traces of the ground having been disturbed which roused his suspicions. He saw the mine and took the dynamite out. Two burghers who were lying in the long grass shouted “Hands up.” Tommy threw his rifle down and with his hands up in the air ran up to the burghers saying, before they could speak, “I say, did you hear the news that Mrs. Botha gave birth to a son in Europe?”

They could not help laughing, and the “Tommy,” looking very innocent, answered:

“I am not telling you a fib.”

One of the burghers coaxed him by telling him they did not doubt his word, only the family news had come so prematurely.

“Well,” returned “Tommy,” “Oi thought you blokes would be interested in your boss’s family, that’s why I spoke.”

The courteous soldier was sent back with instructions to get some better clothes, for those he had on his back were all torn and dirty and they were not worth taking.

The expedition was now a failure, for the enemy had been warned and the sentries were doubled along the line.

In December, 1901, we tried an attack on a British convoy between Lydenburg and Machadodorp. I took a mounted commando and arrived at Schvemones Cleft after four days’ marching through the Sabinek via Cham Sham, an arduous task, as we had to go over the mountains and through some rivers. Some of my officers went out scouting in order to find the best place for an attack on the convoy. The enemy’s blockhouses were found to be so close together on the road along which the convoy had to pass as to make it very difficult to get at it. But having come such a long way nobody liked to go back without having at least made an effort. We therefore marched during the night and found some hiding places along the road where we waited, ready to charge anything coming along. At dawn next day I found the locality to be very little suitable for the purpose we had in view, but if we were now to move the enemy would notice our presence from the blockhouses. We would, therefore, either have to lie low till dusk or make an attack after all. We had already captured several of the enemy’s spies, whom we kept prisoners so as not to be betrayed. Towards the afternoon the convoy came by and we charged on horseback. The English, who must have seen us coming, were ready to receive our charge and poured a heavy fire into us from ditches and trenches and holes in the ground. We managed to dislodge the enemy’s outerflanks and to make several prisoners, but could not reach the carts on account of the heavy fire from a regiment of infantry escorting the waggons. I thought the taking of the convoy would cost more lives than it was worth, and gave orders to cease firing. We lost my brave adjutant, Jaapie Oliver, while Captain Giel Joubert and another burgher were wounded. On the other side Captain Merriman and ten men were wounded. I do not know how many killed he had.

We went back to Schoeman’s Kloof the same day, where we buried our comrades and attended to the wounded. The blockhouses and garrisons along the convoy road were now fortified with entrenchments and guns, and we had to abandon our plan of further attacks. It was raining fast all the time we were out on this expedition, which caused us serious discomfort. We had very few waterproofs, and, all the houses in the district having been burnt down, there was no shelter for man or beast. We slowly retired on Pilgrim’s Rest, having to cross several swollen rivers.

On our arrival at Sabi I received the sad tidings that four burghers named Stoltz had been cruelly murdered by kaffirs at Witriver. Commandant Du Toit had gone there with a patrol and found the bodies in a shocking condition, plundered and cut to pieces with assegais, and, according to the trace, the murderers had come from Nelspruit Station.

Another report came from General Muller at Steenkampsberg. He informed me that he had stormed a camp during the night of the 16th December, but had been forced to retire after a fierce fight, losing 25 killed and wounded, amongst whom was the valiant Field-Cornet J. J. Kriege. The enemy’s losses were also very heavy, being 31 killed and wounded, including Major Hudson.

It should not be imagined that we had to put up with very primitive arrangements in every respect. Where we were now stationed, to the north of Lydenburg, we even had telephonic communication between Spitskop and Doornhoek, with call-offices at Sabi and Pilgrim’s Rest. The latter place is in the centre of the diggers’ population here, and a moderate-sized village. There are a few hundred houses in it, and it is situated 30 miles north-east of Lydenburg. Here are the oldest goldfields known in South Africa, having been discovered in 1876. This village had so far been permanently in our possession. General Buller had been there with his force in 1900 but had not caused any damage, and the enemy had not returned since. The mines and big stamp-batteries were protected by us and kept in order by neutral persons under the management of Mr. Alex. Marshall. We established a hospital there under the supervision of Dr. A. Neethling. About forty families were still in residence and there was enough food, although it was only simple fare and not of great variety. Yet people seemed to be very happy and contented so long as they were allowed to live among their own people.

CHAPTER XLIV

THE LAST CHRISTMAS OF THE WAR.

December, 1901, passed without any important incident. We only had a few insignificant outpost skirmishes with the British garrison at Witklip to the south of Lydenburg. Both belligerents in this district attempted to annoy each other as much as possible by blowing up each other’s mills and storehouses. Two of the more adventurous spirits amongst my scouts, by name Jordaan and Mellema, succeeded in blowing up a mill in the Lydenburg district used by the British for grinding corn, and the enemy very soon retaliated by blowing up one of our mills at Pilgrim’s Rest. As the Germans say, “Alle gute dingen sind drei.” [“All good things come in threes.” – ed.] Several such experiences and the occasional capture of small droves of British cattle were all the incidents worth mentioning. It was in this comparatively quiet manner that the third year of our campaign came to a termination. The War was still raging and our lot was hard, but we did not murmur. We decided rather to extract as much pleasure and amusement out of the Christmas festivities as the extraordinary circumstances in which we found ourselves rendered possible.

The British for the time being desisted from troubling us, and our stock and horses being in excellent condition, we arranged to hold a sort of gymkhana on Christmas Day. In the sportive festivities of the day many interesting events took place. Perhaps the most noteworthy of these were a mule race, for which nine competitors entered, and a ladies’ race, in which six fair pedestrians took part. The spectacle of nine burly, bearded Boers urging their asinine steeds to top speed by shout and spur provoked quite as much honest laughter as any theatrical farce ever excited. We on the grand stand were but a shaggy and shabby audience, but we were in excellent spirits and cheered with tremendous gusto the enterprising jockey who won this remarkable “Derby.” Shabby as we were, we subscribed £115 in prizes. After the sports I have just described the company retired to a little tin church at Pilgrim’s Rest, and there made merry by singing hymns and songs round a little Christmas tree.

Later in the evening a magic-lantern, which we had captured from the British, was brought into play, and with this we regaled 90 of our juvenile guests. The building was crowded and the utmost enthusiasm reigned. The ceremony was opened by the singing of hymns and the making of speeches, a harmonium adding largely to the enjoyment of the evening. I felt somewhat nervous when called upon to address the gathering, for the children were accompanied by their mothers, and these stared at me with expectant eyes as if they would say, “See, the General is about to speak; his words are sure to be full of wisdom.” I endeavoured to display great coolness, and I do not think I failed very markedly as an extemporaneous orator. I was helped very considerably in the speechmaking part of the programme by my good friends the Rev. Neethling and Mr. W. Barter, of Lydenburg. I have not now the slightest idea of what I spoke about except that I congratulated the little ones and their mothers on being preserved from the Concentration Camps, where so many of their friends were confined.

I have mentioned that there were young ladies with us who participated in the races. These were some whom the British had kindly omitted to place in the Concentration Camps, and it was remarkable to see how soon certain youthful and handsome burghers entered into amorous relations with these young ladies, and matters developed so quickly that I was soon confronted with a very curious problem. We had no marriage officers handy, and I, as General, had not been armed with any special authority to act as such. Two blushing heroes came to me one morning accompanied by clinging, timorous young ladies, and declared that they had decided that since I was their General I had full authority to marry them. I was taken aback by this request, and asked, “Don’t you think, young fellows, that under the circumstances you had better wait a little till after the termination of the war?” “Yes,” they admitted, “perhaps it would be more prudent, General, but we have been waiting three years already!”

In General De la Rey’s Commando, which comprised burghers from eight large districts, it had been found necessary to appoint marriage officers, and quite a large number of marriages were contracted. I mention this to show how diversified are the duties of the Boer general in war-time, and what sort of strange offices he is sometimes called upon to perform.

It will be seen from what I have said that occasionally the dark horizon of our veldt life was lit up by the bright sunshine of the lighter elements of life. At most times our outlook was gloomy enough, and our hearts were heavily weighed down by cares. I often found my thoughts involuntarily turning to those who had so long and so faithfully stood shoulder to shoulder with me through all the vicissitudes of war, fighting for what we regarded as our holy right, to obtain which we were prepared to sacrifice our lives and our all. Unconsciously I recalled on this Christmas Day the words of General Joubert addressed to us outside Ladysmith in 1899: “Happy the Africander who shall not survive the termination of this War.” Time will show, if it have not already shown, the wisdom of General Joubert’s words.

Just about this time rumours of various kinds were spread abroad. From several sources we heard daily that the War was about to end, that the English had evacuated the country because their funds were exhausted, that Russia and France had intervened, and that Lord Kitchener had been captured by De Wet and liberated on condition that he and his troops left South Africa immediately. It was even said that General Botha had received an invitation from the British Government to come and arrange a Peace on “independence” lines.

Nobody will doubt that we on the veldt were desperately anxious to hear the glad tidings of Peace. We were weary of the fierce struggle, and we impatiently awaited the time when the Commandant-General and the Government should order us to sheathe the sword.

But the night of the Old Year left us engaged in the fierce conflict of hostilities, and the dawn of the New Year found us still enveloped in the clouds of war—clouds whose blackness was relieved by no silver lining.

CHAPTER XLV

MY LAST DAYS ON THE VELDT.

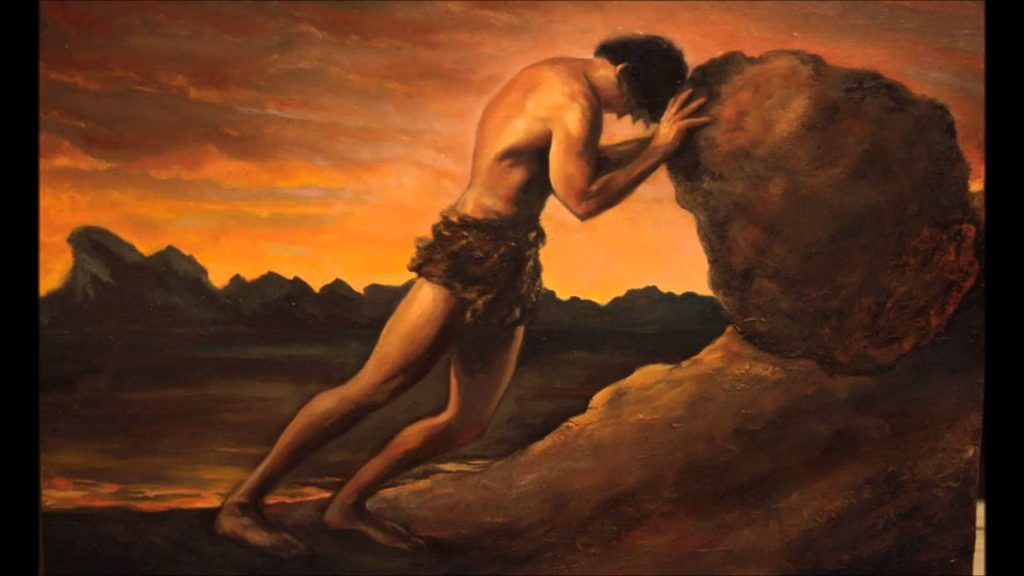

The first month of 1902 found the storm of death and destruction still unabated, and the prospect appeared as dark as at the commencement of the previous year. Our hand, however, was on the plough, and there was no looking back. My instructions were, “Go forward and persevere.”

To the south of Lydenburg, where a section of my commando under General Muller was operating, the enemy kept us very busy, for they had one or more columns engaged. We, to the north of Lydenburg, had a much calmer time of it than our brethren to the south of that place, for there the British were pursuing their policy of exhausting our people with unsparing hand. I attribute the fact that we in the north were left comparatively undisturbed to the mountainous nature of the country. It would have been impossible for the British to have captured us or to have invaded our mountain recesses successfully without a tremendous force, and, obviously, the British had no such force at their disposal. Probably also the British had some respect for the prowess of my commando. An English officer afterwards told me in all seriousness that the British Intelligence Department had information that I was prowling round to the north of Lydenburg with 4,000 men and two cannons, and that my men were so splendidly fortified that our position was unconquerable. Of course, it was not in my interest to enlighten him upon the point. I was a prisoner-of-war when this amusing information was given me, and I simply answered: “Yes, your intelligence officers are very smart fellows.” The officer then inquired, with an assumption of candour and innocence, whether it was really a fact that we had still cannon in the field. To this I retorted: “What would you think if I put a similar question to a British officer who had fallen into my hands?” At this he bit his thumb and stammered: “I beg your pardon; I did not mean to—er—insult you.” He was quite a young chap this, a conceited puppy, affecting the “haw-haw,” which seems to be epidemic in the British Army. His hair was parted down the centre, in the manner so popular among certain British officers, and this style of hair-dressing came to be described by the Boers as “middel-paadje” (middle-path). As a matter of fact, my men only numbered as many hundreds as the thousands attributed to me by the British. As for cannons, they simply existed in the imagination of the British Intelligence Department.

Affairs were daily growing more critical. Since the beginning of the year we had made several attempts at destroying the Delagoa Bay Railway, but the British had constructed so formidable a network of barbed wire, and their blockhouses were so close together and strongly garrisoned, that hitherto our attempts had been abortive. The line was also protected by a large number of armoured trains.

In consequence of our ill-success in this enterprise, we turned our attention to other directions. We reconnoitred the British garrisons in the Lydenburg district with the object of striking at their weakest point. A number of my officers and men proceeded under cover of darkness right through the British outposts, and gained the Lydenburg village by crawling on their hands and knees. On their return journey they were challenged and fired on several times, and managed only with difficulty to return to camp unhurt. The object of the reconnaissance was, however, accomplished. They reported to me that the village was encompassed with barbed wire, and that a number of blockhouses had been built round it, and also that various large houses of the village had been barricaded and were strongly occupied. My two professional scouts, Jordaan and Mellema, had also reconnoitred the village from another direction, and had brought back confirmatory information and the news that Lydenburg was occupied by about 2,000 British soldiers, consisting of the Manchester Regiment and the First Royal Irish, together with a corps of “hands-uppers” under the notorious Harber. Three other Boer spies scouting about the forts on the Crocodile Heights also brought in discouraging reports.

At the Council of War which then took place, and over which I presided, these reports were discussed, and we agreed to attack the two blockhouses nearest the village, and thereafter to storm the village itself. I should mention that it was necessary for us to capture the blockhouses before attempting to take the village itself, for had we left them intact we should have run the danger of having our retreat cut off.

The attack was to take place next night, and as we approached the British lines on horseback, between Spekboom River and Potloodspruit, we dismounted, and proceeded cautiously on foot. One of the objective blockhouses was on the waggon path to the north of the village, and the other was 1,000 yards to the east of Potloodspruit. Field-Cornet Young, accompanied by Jordaan and Mellema, crept up to within 10 feet of one of these blockhouses, and brought me a report that the barbed wire network which surrounded it rendered an assault an impossible task in the darkness. Separating my commando of 150 men into two bodies, I placed them on either side of the blockhouse, sending, in the meanwhile, four men to cut down the wire fences. These men had instructions to give us a signal when they had achieved this object, so that we could then proceed to storm the fort. It would have been sacrificing many in vain to have attempted to proceed without effecting the preliminary operation of fence cutting, since, if we had stormed a blockhouse without first removing the wire, we should have become entangled in the fences and have offered splendid targets to the enemy at a very short range, and our losses would, without doubt, have been considerable.

My fence-cutters stuck doggedly to their task despite the fact that they were being fired upon by the sentries on guard. It was a long and weary business, but we patiently waited, lying on the ground. Towards 2 o’clock in the morning the officer in command of the wire-cutters returned to us, stating that they had accomplished their object in cutting the first wire barrier, but had come across another which it would require several hours to cut through. The sentries had, in the meantime, grown unpleasantly vigilant, and were now frequently firing on our men. They were often so close that at one time, in the darkness, they might have knocked up against the Boers who were cutting their fences.

It being very nearly 3 o’clock, it appeared to me that the attempt would be ineffectual owing to the approach of daylight, and we were forced to retire before the rays of the rising sun lit the heavens and exposed us to the well-aimed fire of the British. I therefore resolved, after consulting my officers, to retire quietly, and to renew my attempt a week later at another point. We returned to camp much disappointed, but consoled ourselves with the hope that success would attend our next efforts.