Editor’s note: Here follow Chapters 21 through 26 of My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, by General Ben Viljoen (published 1902). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XXI

A GOVERNMENT IN FLIGHT.

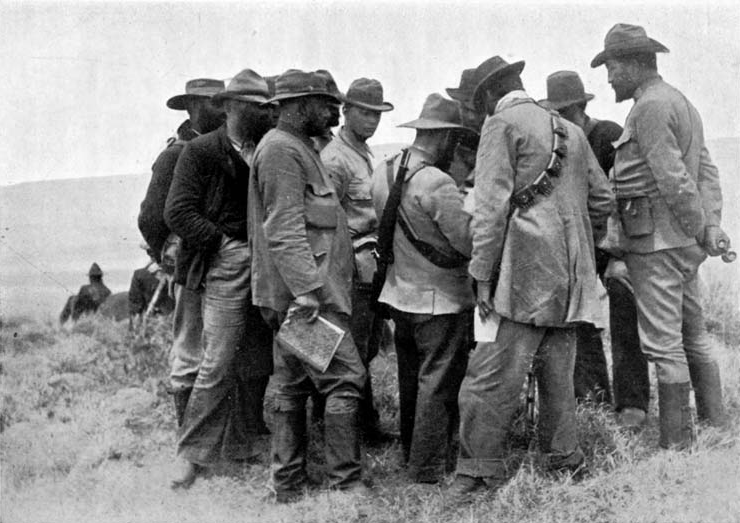

About this time President Steyn arrived from the Orange Free State and had joined President Kruger, and the plan of campaign for the future was schemed. It was also decided that Mr. Schalk Burger should assume the acting Presidentship, since Mr. Kruger’s advanced age and feeble health did not permit his risking the hardships attendant on a warlike life on the veldt.

It was decided Mr. Kruger should go to Europe and Messrs. Steyn and Burger should move about with their respective commandos. They were younger men and the railway, would soon have to be abandoned.

We spent the first weeks of September at Godwan River and Nooitgedacht Station, near the Delagoa Bay railway, and had a fairly quiet time of it. General Buller had meanwhile pushed on with his forces via Lydenburg in the direction of Spitskop and the Sabi, on which General Botha had been compelled to concentrate himself after falling back, fighting steadily, while General French threatened Barberton.

I had expected Pole-Carew to force me off the railway line along which we held some rather strong positions, and I intended to offer a stout resistance. But the English general left me severely alone, went over Dwaalheuvel by an abandoned wagon-track, and crossed the plateau of the mountains, probably to try and cut us off through the pass near Duivelskantoor. I tried hard, with the aid of 150 burghers, to thwart his plans and we had some fighting. But the locality was against us, and the enemy with their great force of infantry and with the help of their guns forced us to retire.

About the 11th of September I was ordered to fall back along the railway, via Duivelskantoor and Nelspruit Station, since General Buller was threatening Nelspruit in the direction of Spitskop, while General French, with a great force, was nearing Barberton. It appeared extremely likely that we should be surrounded very soon. We marched through the Godwan River and over the colossal mountain near Duivelskantoor, destroying the railway bridges behind us. The road we followed was swamped by the heavy rains and nearly impassable. Carts were continually being upset, breakdowns were frequent, and our guns often stuck in the swampy ground. To make matters worse, a burgher on horseback arrived about midnight to tell us that Buller’s column had taken Nelspruit Station, and cut off our means of retreat. Yet we had to pass Nelspruit; there was no help for it. I gave instructions for the waggons and carts (numbering over a hundred), to push on as quickly as possible, and sent out a strong mounted advance guard to escort them.

I myself went out scouting with some burghers, for I wanted to find out before daybreak whether Nelspruit was really in the hands of the enemy or not. In that case our carts and guns would have to be destroyed or hidden, while the commando would have to escape along the footpaths. We crept up to the station, and just at dawn, when we were only a hundred paces away from it, a great fire burst out, accompanied by occasional loud reports. This somewhat reassured me. I soon found our own people to be in possession burning things, and the detonations were obviously not caused by the bursting of shells fired from field-pieces. On sending two of my adjutants—Rokzak and Koos Nel—to the station to obtain further details, they soon came back to report that there was nobody there except a nervous old Dutchman. The burgher, who had told me Nelspruit was in the hands of the enemy, must have dreamt it.

The conflagration I found was caused by a quantity of “kastions” and ammunition-waggons which had been set afire on the previous day, while the explosions emanated from the shells which had been left among their contents.

The enemy’s advance guard had pushed on to Shamoham and Sapthorpe, about 12 miles from the railway, enabling the whole of my commando to pass. We arrived at Nelspruit by eight o’clock. That day we rested and discussed future operations, feeling that our prospects seemed to grow worse every day.

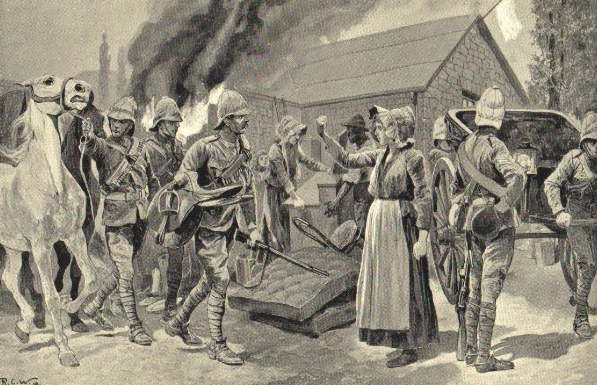

The station presented a sad spectacle. Many trucks loaded with victuals, engines, and burst gun-carriages—everything had been left behind at the mercy of the first-comer, while a large number of kaffirs were plundering and stealing. Only the day before the Government had had its seat there, and how desolate and distressing the sight was now! The traces of a fugitive Government were unmistakable. Whatever might have been our optimism before, however little inclination the burghers might have felt to surrender, however great the firmness of the officers, and their resolve to keep the beloved “Vierkleur” flying, scenes like those at Nooitgedacht, and again at Nelspruit, were enough to make even the strongest and most energetic lose all courage. Many men could not keep back their tears at the disastrous spectacle, as they thought of the future of our country and of those who had been true to her to the last.

Kaffirs, as I said, had been making sad havoc among the provisions, clothes and ammunition, and I ordered them to be driven away. Amongst the many railway-waggons I found some loaded with clothes the fighting burghers had in vain and incessantly been asking for, also cannon and cases of rifle ammunition. We also came across a great quantity of things belonging to our famous medical commission, sweets, beverages, etc. The suspicion which had existed for some considerable time against this commission was, therefore, justified. There was even a carriage which had been used by some of its members, beautifully decorated, with every possible comfort and luxury, one compartment being filled with bottles of champagne and valuable wines. My officers, who were no saints, saw that our men were well provided for out of these. The remainder of the good things was shifted on to a siding, where about twenty engines were kept. By great good luck the Government commissariat stock, consisting of some thousands of sheep, and even some horses, had also been left behind. But we were not cheered.

Among the many questions asked regarding this sad state of affairs was one put by an old burger:

“Dat is nou die plan, want zooals zaken hier lyk, dan heeft die boel in wanhoop gevlug.” (“Is that the plan, then? For from what I can see of it, they have all fled in despair.”)

I answered, “Perhaps they were frightened away, Oom.”

“Ja,” he said, “but look, General, it seems to me as if our members of the Government do not intend to continue the war. You can see this by the way they have now left everything behind for the second time.”

“No, old Oom,” I replied, “we should not take any notice of this. Our people are wrestling among the waves of a stormy ocean; the gale is strong, and the little boat seems upon the point of capsizing, but, it has not gone down as yet. Now and then the boat is dashed against the rocks and the splinters fly, but the faithful sailors never lose heart. If they were to do that the dinghy would soon go under, and the crew would disappear for ever. It would be the last page of their history, and their children would be strangers in their own country. You understand, Oom?”

“Yes, General, but I shall not forget to settle up, for I myself and others with me have had enough of this, and the War has opened our eyes.”

“All right, old man.” I rejoined, “nobody can prevent you surrendering, but I have now plenty of work to do; so get along.”

Burghers of different commandos who had strayed—some on purpose—passed us here in groups of two or ten or more. Some of them were going to their own districts, right through the English lines, others were looking for their cattle, which they had allowed to stray in order to evade the enemy. I could only tell them that the veldt between Nelspruit and Barberton up to Avoca, was, so far as I had been able to discover, full of cattle and waggons belonging to farmers who now had no chance of escaping. Everybody wanted some information from the General.

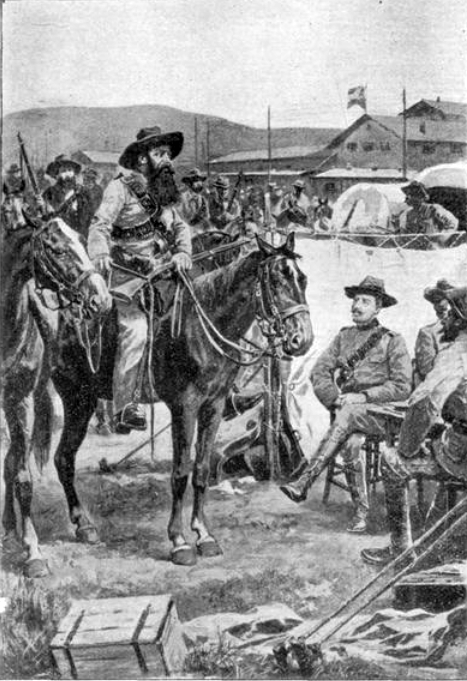

About half a score of burghers with bridle horses then came up. There was one old burgher among them with a long beard, a great veldt hat, and armed with a Mauser which seemed hardly to have been used. He carried two belts with a good stock of cartridges, a revolver, and a tamaai (long sjambok). This veteran strode up in grand martial style to where I was sitting having something to eat. As he approached he looked brave enough to rout the whole British army.

“Dag!” (Good morning.) “Are you the General?” asked the old man.

“Yes, I have the honour of being called so. Are you a field-marshal, a Texas Jack, or what?”

“My name is Erasmus, from the Pretoria district,” he replied, “and my nine comrades and myself, with my family and cattle, have gone into the bush. I saw them all running away, the Government and all. You are close to the Portuguese border, and my mates and I want to know what your plans are.”

“Well,” Mr. Erasmus, I returned, “what you say is almost true; but as you say you and your comrades have been hiding in the bush with your cattle and your wives, I should like to know if you have ever tried to oppose the enemy yet, and also what is your right to speak like this.”

“Well, I had to flee with my cattle, for you have to live on that as well as I.”

“Right,” said I; “what do you want, for I do not feel inclined to talk any longer.”

“I want to know,” he replied, “if you intend to retire, and if there is any chance of making peace. If not, we will go straight away to Buller, and ‘hands-up,’ then we shall save all our property.”

“Well, my friend,” I remarked, “our Government and the Commandant-General are the people who have to conclude peace, and it is not for you or me, when our family and cattle are in danger, to surrender to the enemy, which means turning traitor to your own people.”

“Well, yes; good-bye, General, we are moving on now.”

I sent a message to our outposts to watch these fellows, and to see if they really were going over to the enemy. And, as it happened, that same night my Boers came to camp with the Mausers and horses Erasmus and his party had abandoned. They had gone over to Buller.

The above is but an instance illustrating what often came under my notice during the latter period of my command. This sort of burgher, it turned out, invariably belonged to a class that never meant to fight. In many cases we could do better without them, for it was always these people who wanted to know exactly what was “on the cards,” and whenever things turned out unpleasantly, they only misled and discouraged others. Obviously, we were better off without them.

CHAPTER XXII

AN IGNOMINIOUS DISPERSAL.

Commandant-General Botha, who was then invalided at Hector’s Spruit Station, now sent word that we were to join him there without delay. He said I could send part of the commando by train, but the railway arrangements were now all disturbed, and everything was in a muddle. As nothing could be relied on in the way of transport, the greater number of the men and most of the draught beasts had to “trek.”

At Crocodile Gat Station the situation was no better than at Nelspruit, and the same might be said of Kaapmuiden. Many of the engine drivers, and many of the burghers even, who were helping in destroying the barrels of spirits at the stations, were so excited (as they put it) through the fumes of the drink, that the strangest things were happening. Heavily-laden trains were going at the rate of 40 miles an hour. A terrible collision had happened between two trains going in different directions, several burghers and animals being killed. Striplings were shooting from the trains at whatever game they saw, or fancied they saw, along the line, and many mishaps resulted. These things did not tend to improve matters.

It was not so much that the officers had lost control over their men. It seemed as if the Evil Spirit had been let loose and was doing his very best to encourage the people to riotous enjoyment.

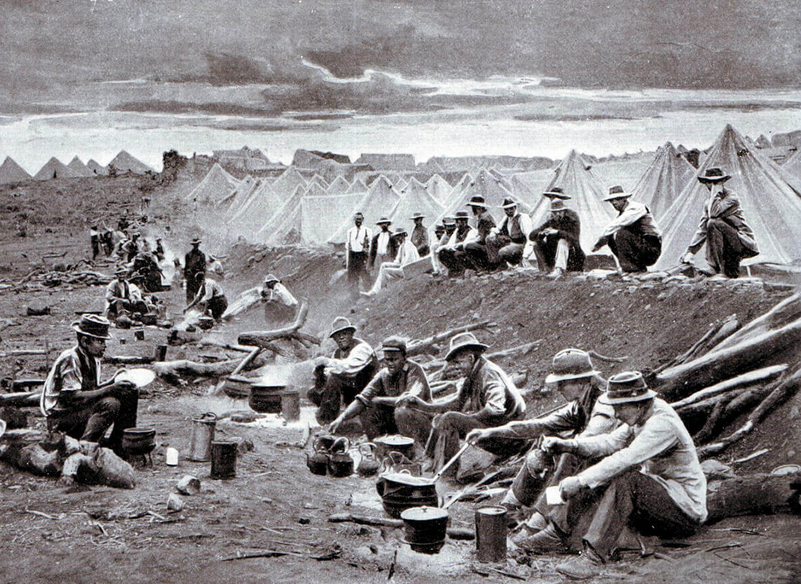

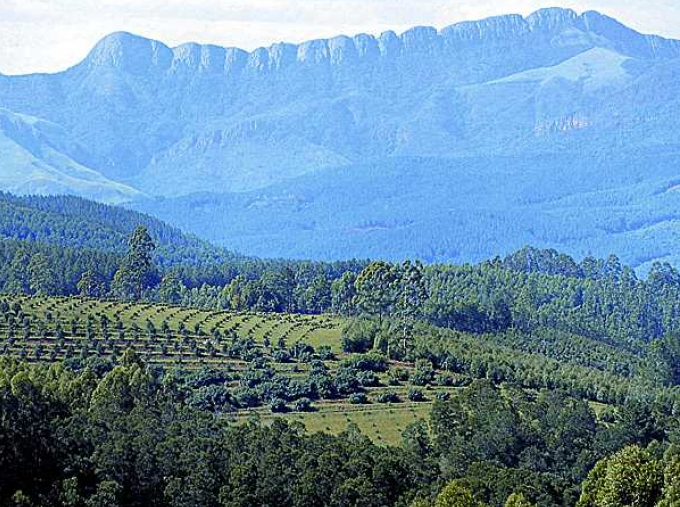

Hector’s Spruit is the last station but one before you come to the Portuguese frontier, and about seventeen miles from Ressano Garcia. Here every commando stopped intending of course to push on to the north and then to cross the mountains near Lydenburg in a westerly direction. The day when I arrived at Hector’s Spruit, President Steyn, attended by an escort of 100 men, went away by the same route. Meanwhile General Buller was encamped at Glyn’s mines near Spitskop and the Sabi River, which enabled him to command the mountain pass near Mac Mac and Belvedere without the slightest trouble, and to block the roads along which we meant to proceed. Although the late Commandant (afterwards fighting General) Gravett occupied one of the passes with a small commando, he was himself in constant danger of being cut off from Lydenburg by a flank movement. On the 16th of September, 1900, an incident occurred which is difficult to describe adequately. Hector Spruit is one of the many unattractive stations along the Delegoa Bay railway situated between the great Crocodile river and dreary black “kopjes” or “randjes” with branches of the Cape mountains intervening and the “Low Veldts,” better known as the “Boschveldt.” This is a locality almost filled with black holly bushes, where you can only see the sky overhead and the spot of ground you are standing on. In September the “boschveldt” is usually dry and withered and the scorching heat makes the surroundings seem more lugubrious and inhospitable than ever.

The station was crowded with railway carriages loaded up with all sorts of goods, and innumerable passenger carriages, and the platform and adjoining places filled with agitated people. Some were packing up, others unpacking, and some, again, were looting. The majority were, however, wandering about aimlessly. They did not know what was happening; what ought to be done or would be done; and the only exceptions were the officers, who were busily engaged in providing themselves and their burghers with provisions and ammunition.

I now had to perform one of the most unpleasant duties I have ever known: that of calling the burghers together and telling them that those who had no horses were to go by train to Komati Poort, there to join General Jan Coetser. Those who had horses were to report themselves to me the next morning, and get away with me through the low fields.

Some burghers exclaimed: “We are now thrown over, left in the ‘lurch,’ because we have not got horses; that is not fair.”

Others said they would be satisfied if I went with them, for they did not know General Coetser.

Commandant-General Botha did not see his way to let me go to Komati Poort, as he could not spare me and the other commandos. Those of the men who had to walk the distance complained very bitterly, and their complaints were well-founded. I did my best to persuade and pacify them all, and some of them were crying like babies when we parted.

Komati Poort was, of course, the last station, and if the enemy were to drive them any further they would have to cross the Portuguese border, and to surrender to the Portuguese; or they could try to escape through Swaziland (as several hundreds did afterwards) or along the Lebombo mountains, via Leydsdorp. But if they took the latter route then they might just as well have stayed with me in the first place. It was along this road that General Coetser afterwards fled with a small body of burghers, when the enemy, according to expectations, marched on Komati Poort, and met with no resistance, though there were over 1800 there of our men with guns.

A certain Pienaar, who arrogated unto himself the rank of a general on Portuguese territory, fled with 800 men over the frontier. These, however, were disarmed and sent to Lisbon.

The end of the struggle was ignominious, as many a burgher had feared; and to this day I pity the men who, at Hector’s Spruit, had to go to Komati Poort much against their will.

Fortunately they had the time and presence of mind to blow up the “Long Tom” and other guns before going; but a tremendous lot of provisions and ammunition must have fallen into the hands of the enemy.

At Hector’s Spruit half a score of cannon of different calibre had been blown up, and many things buried which may be found some day by our progeny. Our carts were all ready loaded, and we were prepared to march next morning into the desert and take leave of our stores. How would we get on now? Where would we get our food, cut off as we were from the railway, and, consequently, from all imports and supplies? These questions and many others crossed our minds, but nobody could answer them.

Our convoys were ready waiting, and the following morning we trekked into the Hinterland Desert, saying farewell to commissariats and stores.

The prospect was melancholy enough. By leaving Hector’s Spruit we were isolating ourselves from the outer world, which meant that Europe and civilisation generally could only be informed of our doings through English channels.

Once again our hopes were centred in our God and our Mausers.

Dr. Conan Doyle says about this stage of the war:—

“The most incredulous must have recognised as he looked at the heap of splintered and shattered gunmetal (at Hector’s Spruit) that the long War was at last drawing to a close.”

And here I am, writing these pages seventeen months later, and the War is not over yet. But Dr. Doyle is not a prophet, and cannot be reproached for a miscalculation of this character, for if I, and many with me, had been asked at the time what we thought of the future, we might have been as wide of the mark as Dr. Doyle himself.

CHAPTER XXIII

A DREARY TREK THROUGH FEVERLAND.

The 18th of September, 1900, found us trekking along an old disused road in a northerly direction. We made a curious procession, an endless retinue of carts, waggons, guns, mounted men, “voetgangers” nearly three miles long. The Boers walking comprised 150 burghers without horses, who refused to surrender to the Portuguese, and who had now joined the trek on foot. Of the 1,500 mounted Boers 500 possessed horses which were in such a parlous condition that they could not be ridden. The draught cattle were mostly poor and weak, and the waggons carrying provisions and ammunition, as also those conveying the guns, could only be urged along with great difficulty. In the last few months our cattle and horses had been worked hard nearly every day, and had to be kept close to our positions.

During the season the veldt in the Transvaal is in the very worst condition, and the animals are then poorer than at any other period. We had, moreover, the very worst of luck, kept as we were in the coldest parts of the country from June till September, and the rains had fallen later than usual. There was, therefore, scarcely any food for the poor creatures, and hardly any grass. The bushveldt through which we were now trekking was scorched by an intolerable heat, aggravated by drought, and the temperature in the daytime was so unbearable that we could only trek during the night.

Water was very scarce, and most of the wells which, according to old hunters with us, yielded splendid supplies, were found to be dried up. The veldt being burned out there was not a blade of grass to be seen, and we had great trouble in keeping our animals alive. From time to time we came across itinerant kaffir tribes from whom we obtained handfuls of salt or sugar, or a pailful of mealies, and by these means we managed to save our cattle and horses.

When we had got through the Crocodile River the trek was arranged in a sort of military formation enabling us to defend ourselves, had we been attacked. The British were already in possession of the railway up to Kaapmuiden and we had to be prepared for pursuit; and really pursuit by the British seemed feasible and probable from along the Ohrigstad River towards Olifant’s Nek and thence along the Olifant’s River.

Our original plan was to cross the Sabi, along the Meritsjani River, over the mountains near Mac Mac, through Erasmus or Gowyn’s Pass and across Pilgrim’s Rest, where we might speedily have reached healthier veldt and better climatic conditions. President Steyn had passed there three days previously, but when our advance guard reached the foot of the high mountains, near Mac Mac, the late General Gravett sent word that General Buller with his force was marching from Spitskop along the mountain plateau and that it would be difficult for us to get ahead of him and into the mountains. The road, which was washed away, was very steep and difficult and contained abrupt deviations so that we could only proceed at a snail’s pace.

Commandant-General Botha then sent instructions to me to take my commando along the foot of the mountains, via Leydsdorp, while he with his staff and the members of the Government would proceed across the mountains near Mac Mac. General Gravett was detailed to keep Buller’s advance guard busy, and he succeeded admirably.

I think it was here that the British lost a fine chance of making a big haul. General Buller could have blocked us at any of the mountain roads near Mac Mac, and could also have swooped down upon us near Gowyn’s Pass and Belvedere. At the time of which I write Buller was lying not 14 miles away at Spitskop. Two days after he actually occupied the passes, but just too late to turn the two Governments and the Commandant-General. It might be said that they could in any case have, like myself, escaped along the foot of the mountains via Leydsdorp to Tabina and Pietersburg, but had the way out been blocked to them near Mac Mac, our Government and generalissimo would have been compelled to trek for at least three weeks in the low veldt before they could have reached Pietersburg, during which time all the other commandos would have been out of touch with the chief Boer military strategists and commanders, and would not have known what had become of their military leaders or of their Government. This would have been a very undesirable state of affairs, and would very likely have borne the most serious consequences to us. The British, moreover, could have occupied Pietersburg without much trouble by cutting off our progress in the low veldt, and barring our way across the Sabini and at Agatha. This coup could indeed have been effected by a small British force. In the mountains they would, moreover, have found a healthy climate, while we should have been left in the sickly districts of the low veldt. And had we been compelled to stay there for two months we would have been forced to surrender, for about the middle of October the disease among our horses increased and so serious was the epidemic that none but salted horses survived. The enteric fever would also have wrought havoc amongst us.

Another problem was whether all this would not have put an end to the war; we still had generals left, and strong commandos, and it was, of course, very likely that a great number of Boers driven to desperation would have broken through, although two-thirds of our horses were not fit for a bold dash. Perhaps fifteen hundred out of the two thousand Boers would have made good their escape, but in any case large numbers of wagons, guns, etc. would have fallen into the British hands and our leaders might have been captured as well. The moral effect would have caused many other burghers from the other commandos to have lost heart and this at a moment, too, when they already required much encouragement.

This was my view of the situation, and I think Lord Roberts, or whoever was responsible, lost a splendid opportunity.

As regards my commando at the foot of the Mauch Mountains we turned right about and I took temporary leave of Louis Botha. It was a very affecting parting; Botha pressed my hand, saying, “Farewell, brother; I hope we shall get through all right. God bless you. Let me hear from you soon and frequently.”

That night we encamped at Boschbokrand, where we found a store unoccupied, and a house probably belonging to English refugees, for shop and dwelling had been burgled and looted. After our big laager had been arranged, Boer fashion, and the camp fire threw its lurid light against the weird dark outline of the woods, the Boers grouped themselves over the veldt. Some who had walked twenty miles that day fell down exhausted.

I made the round of the laager, and I am bound to say that in spite of the trying circumstances, my burghers were in fairly cheerful spirits.

I discussed the immediate prospects with the officers, and arranged for a different commando to be placed in the advance guard each day and a different field-cornet in the rear. Boers conversant with the locality were detailed to ride ahead and to scout and reconnoitre for water.

When I returned that night to my waggon the evening meal was ready, but for the first time in my life I could eat nothing. I felt too dejected. My cook, Jan Smith, and my messmates were curious to know the reason I did not “wade in,” for they always admired my ferocious appetite.

It had been a tiring day, and I pretended I was not well; and soon afterwards I lay down to rest.

I had been sitting up the previous evening till late in the night, and was therefore in hopes of dropping off to sleep. But whatever I tried—counting the stars, closing my eyes and doing my best to think of nothing—it was all in vain.

Insurmountable difficulties presented themselves to me. I had ventured into an unhealthy, deserted, and worst of all, unknown part of the country with only 2,000 men. I was told we should have to cover 300 miles of this enteric-stricken country.

The burghers without horses were suffering terribly from the killing heat, and many were attacked by typhoid and malarial fever through having to drink a lot of bad water; these enemies would soon decimate our commando and reduce its strength to a minimum. And for four or five weeks we should be isolated from the Commandant-General and from all white men.

Was I a coward, then, to lie there, dejected and even frightened? I asked myself. Surely, to think nothing of taking part in a fierce battle, to be able to see blood being shed like water, to play with life and death, one could not be without some courage? And yet I did not seem to have any pluck left in me here where there did not seem to be much danger.

These and many similar thoughts came into my head while I was trying to force myself to sleep, and I told myself not to waver, to keep a cool head and a stout heart, and to manfully go on to the end in order to reach the goal we had so long kept in view.

Ah, well, do not let anybody expect a general to be a hero, and nothing else, at all times; let us remember that “A man’s a man for a’ that,” and even a fighting man may have his moments of weakness and fear.

The next morning, about four o’clock, our little force woke up again. The cool morning air made it bearable for man and beast to trek. This, however, only lasted till seven o’clock, when the sun was already scorching, without the slightest sign of a breeze. It became most oppressive, and we were scarcely able to breathe.

The road had not been used for twenty or thirty years, and big trees were growing in our path, and had to be cut down at times. The dry ground, now cut up by the horses’ hoofs, was turned into dust by the many wheels, great clouds flying all round us, high up in the air, covering everything and everybody with a thick layer of ashy-grey powder.

About nine o’clock we reached Zand River, where we found some good water, and stayed till dusk. We exchanged some mealies against salt and other necessaries with some kaffirs who were living near by the water. Their diminutive, deformed stature was another proof of the miserable climate obtaining there.

There was much big game here; wild beasts, “hartebeest,” “rooiboks” (sometimes in groups of from five to twenty at a time), and at night we heard the roaring of lions and the howling of wolves. Even by day lions were encountered. Now, one of the weakest points, perhaps the weakest, of an Afrikander is his being unable to refrain from shooting when he sees game, whether such be prohibited or not. From every commando burghers had been sent out to do shooting for our commissariat, but a good many had slipped away, so that hundreds of them were soon hunting about in the thickly-grown woods. The consequence was that, whenever a group of them discovered game, it seemed as if a real battle were going on, several persons often being wounded, and many cattle killed. We made rules and regulations, and even inflicted punishments which did some good, but could not check the wild hunting instincts altogether, it being difficult to find out in the dark bush who had been the culprits.

Meanwhile the trek went on very slowly. On the seventh day we reached Blyde River, where we had one of the loveliest views of the whole “boschveldt.” The river, which has its source near Pilgrim’s Rest and runs into the great Olifant’s River near the Lomboba, owes its name to trekker pioneers, who, being out hunting in the good old times, had been looking for water for days, and when nearly perishing from thirst, had suddenly discovered this river, and called it Blyde (or “Glad”) River. The stream at the spot we crossed is about 40 feet wide, and the water as pure as crystal. The even bed is covered with white gravel, and along both banks are splendid high trees. The whole laager could outspan under their shade, and it was a delightful, refreshing sensation to find oneself protected from the burning sun. We all drank of the delicious water, which we had seldom found in such abundance, and we also availed ourselves of it to bathe and wash our clothes.

In the afternoon a burgher, whose name I had better not mention, came running up to us with his clothes torn to tatters, and his hat and gun gone. He presented a curious picture. I heard the burghers jeer and chaff him as he approached, and called out to him: “What on earth have you been up to? It looks as if you had seen old Nick with a mask on.”

The affrighted Boer’s dishevelled hair stood on end and he shook with fear.

He gasped: “Goodness gracious, General, I am nearly dead. I had gone for a stroll to do a bit of hunting like, and had shot a lion who ran away into some brushwood. I knew the animal had received a mortal wound, and ran after it. But I could only see a yard or so ahead through the thick undergrowth, and was following the bloodstained track. Seeing the animal I put down my gun and was stepping over the trunk of an old tree; but just as I put my foot down, lo! I saw a terrible monster standing with one paw on the beast’s chest. Oh, my eye! I thought my last hour had come, for the lion looked so hard at me, and he roared so awfully. By jove, General, if this had been an Englishman I should just have “hands-upped,” you bet! But I veered round and went down bang on my nose. My rifle, my hat, my all, I abandoned in that battle, and for all the riches of England, I would not go back. General, you may punish me for losing my rifle, but I won’t go back to that place for anything or anybody.”

I asked him what the lion had done then, but he knew nothing more. Another burgher who stood by, remarked: “I think it was a dog this chap saw. He came running up to me so terrified that he would not have known his own mother. If I had asked him at that moment he would not have been able to remember his own name.”

The poor fellow was roused to indignation, and offered to go with the whole commando and show them the lion’s trail. But there was no time for that, and the hero had a bad time of it, for everybody was teasing and chaffing him, and henceforth he was called the “Terror of the Vaal.”

We should have liked to have lingered a few days near that splendid and wholesome stream. We wanted a rest badly enough, but it was not advisable on account of the fever, which is almost invariably the penalty for sleeping near a river in the low veldt. One of the regulations of our commando forbade the officers and men to spend the night by the side of any water or low spot. It would also have been fatal to the horses, for sickness amongst them and fever always coincide. But they did not always keep to the letter of these instructions. The burghers, especially those who had been walking, or arriving at a river, would always quickly undress and jump into the water, after which some of them would fall asleep on the banks or have a rest under the trees. Both were unhealthy and dangerous luxuries. Many burghers who had been out hunting or had been sent out provisioning, stayed by the riverside till the morning, since they could dispense with their kit in this warm climate. They often were without food for twenty-four hours, unless we happened to trek along the spot where they were resting. To pass the night in these treacherous parts on an empty stomach was enough to give anybody the fever.

When we moved on from Blyde River many draught beasts were exhausted through want of food, and we were obliged to leave half a dozen carts behind. This caused a lot of trouble as we had to transfer all the things to other vehicles, and field-cornets did not like to take up the goods belonging to other field-cornets’ burghers, the cattle being in such a weak condition that it made every man think of his own division. No doubt the burghers were very kind to their animals, but they sometimes carried it too far, and the superior officers had often to interfere.

The distance from Blyde River to the next stopping place could not be covered in one day, and we should have no water the next; not a very pleasant prospect. The great clouds of dust through which we were marching overnight and the scorching heat in the daytime made us all long for water to drink and to clean ourselves. So when the order came from the laager commandants: “Outspan! No water to-day, my boys, you will have to be careful with the water on the carts. We shall be near some stream to-morrow evening,” they were bitterly disappointed.

When we got near the water the following day eight burghers were reported to be suffering badly from the typhoid fever, five of them belonging to the men who were walking. We had a very insufficient supply of ambulance waggons. I had omitted to procure a great number of these indispensable vehicles on leaving Hector’s Spruit, for there had been so many things to look after. We were lucky to have with us brave Dr. Manning, of the Russian Ambulance, who rendered us such excellent assistance, and we have every reason to be thankful to H.M. the Czarina of Russia for sending him out. Dr. Manning had the patients placed in waggons, which had been put at his disposal for this purpose, but notwithstanding his skilled and careful treatment, one of my men died the following day, while the number of those who were seriously ill rose to fifteen. The symptoms of this fatal illness are: headache and a numb feeling in all the limbs, accompanied by an unusually high temperature very often rising to 104 and 106 degrees during the first 24 hours, with the blood running from the patient’s nose and ears, which is an ominous sign. At other times the first symptom is what is commonly called “cold shivers.”

We proceeded slowly until we came to the Nagout River, where the monotony and dreariness of a trek through the “boschveldt” were somewhat relieved by the spectacle of a wide stream of good water, with a luxurious vegetation along the banks. It was a most pleasant and refreshing sight to behold. For some distance along the banks some grass was found, to which the half-starved animals were soon devoting their attention. It was the sort of sweet grass the hunters call “buffalo-grass,” and which is considered splendid food for cattle. We pitched our camp on a hill about one mile from the river, and as our draught-beasts were in want of a thorough rest we remained there for a few days. We had been obliged to drive along some hundreds of oxen, mules, and horses, as they had been unfit to be harnessed for days, and had several times been obliged to leave those behind that were emaciated and exhausted.

From the Nagout River we had to go right up to the Olifant’s River, a distance of about 20 miles, which took us three days. The track led all along through the immense bush-plain which extends from the high Mauch Mountains in the west to the Lebombo Mountains in the east; and yet one could only see a few paces ahead during all these days, and the only thing we could discern was the summit of some mountain on the westerly or easterly horizon, and even the tops of the Mauch and Lebombo Mountains one could only see by standing on the top of a loaded waggon, and with the aid of a field-glass. This thickly-wooded region included nearly one-third of the Transvaal, and is uninhabited, the white men fearing the unhealthy climate, while only some miserable little kaffir tribes were found about there, the bulk being the undisputed territory of the wild animals.

The Olifant’s River, which we had to cross, is over 100 feet wide. The old track leading down to it, was so thickly covered with trees and undergrowth that we had to cut a path through it. The banks of the river were not very high, thus enabling us to make a drift without much trouble. The bed was rocky, and the water pretty shallow, and towards the afternoon the whole commando had crossed. Here again we were obliged to rest our cattle for a few days, during which we had to fulfil the melancholy duty of burying two of our burghers who had died of fever. It was a very sad loss and we were very much affected, especially as one left a young wife and two little children, living at Barberton. The other one was a young colonial Afrikander who had left his parents in the Cradock district (Cape Colony) to fight for our cause. We could not help thinking how intensely sad it was to lose one’s life on the banks of this river, far from one’s home, from relatives and friends, without a last grasp of the hand of those who were nearest and dearest.

The Transvaaler’s last words were:—

“Be sure to tell my wife I am dying cheerfully, with a clear conscience; that I have given my life for the welfare of my Fatherland.”

We had now to leave some draught cattle and horses behind every day, and the number of those who were obliged to walk was continually increasing, till there were several hundred.

Near Sabini, the first river we came to after leaving Leydsdorp we secured twenty-four mules which were of very great use to us under the circumstances. But the difficulty was how to distribute them amongst the field-cornets. The men all said they wanted them very urgently, and at once found the cattle belonging to each cart to be too thin and too weak to move. Yet the twenty-four could only be put into two carts, and I had to solve the difficulty by asserting my authority.

It was no easy task to get over the Agatha Mountains and we had to rest for the day near the big Letaba, especially as we had to give the whole file of carts, guns, etc., a chance of forming up again. Here we succeeded in buying some loads of mealies, which were a real God-send to our half-starved horses. I also managed to hire some teams of oxen from Boers who had taken up a position with their cattle along the Letaba, which enabled us to get our carts out of the Hartbosch Mountains as far as practicable. The task would have been too fatiguing for our cattle. It took us two days before we were out of these mountains, when we camped out on the splendid “plateau” of the Koutboschbergen, where the climate was wholesome and pleasant.

Here, after having passed a whole month in the wilderness of the low veldt, with its destructive climate, it was as though we began a new life, as if we had come back to civilisation. We again saw white men’s dwellings, cultivated green fields, flocks of grazing sheep, and herds of sleek cows.

The inhabitants of the country were not a little surprised, not to say alarmed, to find, early one Sunday morning, a big laager occupying the plateau. A Boer laager always looks twice as large as it really is when seen from a little distance. Some Boer lads presently came up to ask us whether we were friends or enemies, for in these distant parts people were not kept informed of what happened elsewhere.

“A general,” said a woman, who paid us a visit in a trap, “is a thing we have all been longing to see. I have called to hear some news, and whether you would like to buy some oats; but I tell you straight I am not going to take “blue-backs” (Government notes), and if you people buy my oats you will have to pay in gold.”

A burgher answered her: “There is the General, under that cart; ‘tante’ had better go to him.”

Of course I had heard the whole conversation, but thought the woman had been joking. The good lady came up to my cart, putting her cap a little on one side, probably to favour us with a peep at her beauty.

“Good morning. Where is that General Viljoen; they say he is here?”

I thought to myself: “I wonder what this charming Delilah of fifty summers wants,” and got up and shook hands with her, saying: “I am that General.

What can I do for ‘tante’?”

“No, but I never! Are you the General? You don’t look a bit like one; I thought a General looked ‘baing’ (much) different from what you are like.”

Much amused by all this I asked: “What’s the matter with me, then, ‘tante’?”

“Nay, but cousin (meaning myself) looks like a youngster. I have heard so much of you, I expected to see an old man with a long beard.”

I had had enough of this comedy, and not feeling inclined to waste any more civilities on this innocent daughter of Mother Eve, I asked her about the oats.

I sent an adjutant to have a look at her stock and to buy what we wanted, and the prim dame spared me the rest of her criticism.

We now heard that Pietersburg and Warmbad were still held by the Boers, and the road was therefore clear. We marched from here via Haenertsburg, a little village on the Houtboschbergrand, and the seat of some officials of the Boer Mining Department, for in this neighbourhood gold mines existed, which in time of peace give employment to hundreds of miners.

Luckily, there was also a hospital at Haenertsburg, where we could leave half a dozen fever patients, under the careful treatment of an Irish doctor named Kavanagh, assisted by the tender care of a daughter of the local justice of the peace, whose name, I am sorry to say, I have forgotten.

About the 19th of October, 1900, we arrived at Pietersburg, our place of destination.

CHAPTER XXIV

PAINS AND PLEASURES OF COMMANDEERING.

We found Pietersburg to be quite republican, all the officials, from high to low, in their proper places in the offices, and the “Vierkleur” flying from the Government buildings. The railway to Warmbad was also in Boer hands. At Warmbad were General Beyers and his burghers and those of the Waterberg district. Although we had no coals left, this did not prevent us from running a train with a sufficient number of carriages from Pietersburg to Warmbad twice a week. We used wood instead, this being found in great quantities in this part of the country.

Of course, it took some time to get steam up, and we had to put in more wood all the time, while the boilers continually threatened to run dry. We only had two engines, one of which was mostly laid up for repairs. The other one served to keep the commandos at Warmbad provided with food, etc.

The Pietersburgers also had kept up telegraphic communication, and we were delighted to hear that clothes and boots could be got in the town, as we had to replace our own, which had got dreadfully torn and worn out on the “trek” through the “boschveldt.” Each commandant did his best to get the necessary things together for his burghers, and my quarters were the centre of great activity from the early morning to late in the evening, persons who had had their goods commandeered applying to the General and lodging complaints.

After we had been at Pietersburg for eight days, a delay which seemed so many months to me, I had really had too much of it. The complaints were generally introduced by remarks about how much the complainants’ ancestors had done for the country at Boomplaats, Majuba, etc., etc., and how unfairly they were now being treated by having their only horses, or mules, or their carriages, or saddles commandeered.

The worst of it was, that they all had to be coaxed, either with a long sermon, pointing out to them what an honour and distinction it was to be thus selected to do their duty to their country and their people, or by giving them money if no appeal to their generous feelings would avail; sometimes by using strong language to the timid ones, telling them it would have to be, whether they liked it or not.

Anyhow we got a hundred fine horses together at the cost of a good many imprecations. The complainants may be divided into the following categories:—

1st. Those who really believed they had some cause of complaint.

2nd. Those who did not feel inclined to part with anything without receiving the full value in cash—whose patriotism began and ended with money.

3rd. Those who had Anglophile tendencies and thought it an abomination to part with anything to a commando (these were the worst to deal with, for they wore a mask, and we often did not know whether we had got hold of the Evil One’s tail or an angel’s pinions), and

4th. Those who were complaining without reason. These were, as a rule, burghers who did not care to fight, and who remained at home under all sorts of pretexts.

The complaints from females consisted of three classes:—

1st. The patriotic ones who did all they could—sensible ladies as they were—to help us and to encourage our burghers, but who wanted the things we had commandeered for their own use.

2nd. The women without any national sympathy—a tiresome species, who forget their sex, and burst into vituperation if they could not get their way; and

3rd. The women with English sympathies, carefully hidden behind a mask of pro-Boer expressions.

The pity of it was that you could not see it written on their foreheads which category they belonged to, and although one could soon find out what their ideas were, one had to be careful in expressing a decided opinion about them, as there was a risk of being prosecuted for libel.

I myself always preferred an outspoken complaint. I could always cut up roughly refer him to martial law, and gruffly answer, “It will have to be like this, or you will have to do it!” And if that did not satisfy him I had him sent away. But the most difficult case was when the complaint was stammered under a copious flood of tears, although not supported by any arguments worth listening to.

There were a good many foreign subjects at Pietersburg but they were mostly British, and these persons, who also had some of their horses, etc., commandeered, were a great source of trouble, for many Boer officers and burghers treated them without any ceremony, simply taking away what they wanted for their commandos. I did not at all agree with this way of doing things, for so long as a foreign subject, though an Englishman, is allowed to remain within the fighting lines, he has a right to protection and fairness, and no difference ought to be made between him and the burghers who stay at home, when there is any fighting to be done.

From Pietersburg we went to Nylstroom, a village on the railway to which I had been summoned by telegram by the Commandant-General, who had arrived there on his way to the westerly districts, this being the first I had heard of him after we had parted at the foot of the Mauchberg, near Mac Mac.

I travelled by rail, accompanied by one of my commandants. The way they managed to keep up steam was delightfully primitive. We did not, indeed, fly along the rails, yet we very often went at the rate of nine miles an hour!

When our supply of wood got exhausted, we would just stop the train, or the train would stop itself, and the passengers were politely requested to get out and take a hand at cutting down trees and carrying wood. This had a delicious flavour of the old time stage coach about it, when first, second, and third class passengers travelled in the same compartment, although the prices of the different classes varied considerably. When a coach came to the foot of a mountain the travellers would, however, soon find out where the difference between the classes lay, for the driver would order all first-class passengers to keep their seats, second-class passengers to get out and walk, and third-class passengers to get out and push.

We got to our destination, however, although the chances seemed to have been against it. I myself had laid any odds against ever arriving alive.

At Nylstroom we found President Steyn and suite, who had just arrived, causing a great stir in this sleepy little village, which had now become a frontier village of the territory in which we still held sway.

A great popular meeting was held, which President Steyn opened with a manly speech, followed by a no less stirring one from our Commandant-General, both exhorting the burghers to do their duty towards their country and towards themselves by remaining faithful to the Cause, as the very existence of our nation depended on it.

In the afternoon the officers met in an empty hall of the hotel at Nylstroom to hold a Council of War, under the direction of the Commandant-General.

Plans were discussed and arrangements made for the future. I was to march at once from Pietersburg to the north-westerly part of the Pretoria district, and on to Witnek, which would bring us back to our old battle-grounds. The state of the commandos, I was told, in those parts was very sad. The commandant of the Boksburg Commando had mysteriously fallen into the enemy’s hands, and with his treacherous assistance nearly the whole commando had been captured as well. The Pretoria Commando had nearly shared this melancholy fate.

That same night we travelled to Pietersburg. After we had passed Yzerberg the train seemed to be going more and more slowly, till we came to a dead stop. The engine had broken down, and all we could do was to get out and walk the rest of the way. In a few hours’ time, to our great joy, the second, and the only other train from Pietersburg there was, came up.

After having convinced the engine-driver that he had to obey the General’s orders, he complied with our request to take us to Pietersburg, and at last, after a lot of trouble, we arrived the following day. Our cattle and horses were now sufficiently rested and in good condition. The commandos have been provided with the things they most urgently needed, and ordered to be ready within two days.

CHAPTER XXV

PUNISHING THE PRO-BRITISH.

During the first days of November, 1900, we went from Pietersburg to Witnek, about nineteen miles north of Bronkhorst Spruit, in the Pretoria district. We had enjoyed a fortnight’s rest, which had especially benefited our horses, and our circumstances were much more favourable in every respect when we left Pietersburg than when we had entered it.

The Krugersdorp Commando had been sent to its own district, from Pietersburg via Warmbad and Rustenburg, under Commandant Jan Kemp, in order to be placed under General De la Rey’s command. Most of the burghers preferred being always in their own districts, even though the villages scattered about were in the enemy’s hands, the greater part of the homesteads burnt down and the farms destroyed, and nearly all the families had been placed in British Concentration Camps; and if the commanding officers would not allow the burghers to go to their own districts they would simply desert, one after the other, to join the commando nearest their districts.

I do not think there is another nation so fondly attached to their home and its neighbourhood, even though the houses be in ruins and the farms destroyed. Still the Boer feels attracted to it, and when he has at last succeeded in reaching it, you will often find him sit down disconsolately among the ruins or wandering about in the vicinity.

It was better, therefore, to keep our men somewhere near their districts, for even from a strategical point of view they were better there, knowing every nook and cranny, which enabled them to find exactly where to hide in case of danger. Even in the dark they were able to tell, after scouting, which way the enemy would be coming. This especially gave a commando the necessary self-reliance, which is of such great importance in battle. It has also been found during the latter part of the War to be easier for a burgher to get provisions in his own district than in others, notwithstanding the destruction caused by the enemy.

Commandant Muller, of the Boksburg Commando, one of those who were lucky enough to escape the danger of being caught through the half-heartedness of the previous commandant (Dirksen), and had taken his place, arrived at Warmbad almost the same moment. He proceeded via Yzerberg and joined us at Klipplaatdrift near Zebedelestad.

I had allowed a field-cornet’s company, consisting of Colonial Afrikanders, to accompany President Steyn to the Orange Free State, which meant a reduction of my force of 350 men, including the Krugersdorpers. But the junction with the Boksburg burghers, numbering about 200 men, somewhat made up for it.

We went along the Olifant’s River, by Israelskop and Crocodile Hill, to the spot where the Eland’s River runs into the Olifant’s River, and thence direct to Witnek through Giftspruit.

The grass, after the heavy rains, was in good condition and yielded plenty of food for our quadrupeds. Strange to say, nothing worth recording occurred during this “trek” of about 95 miles. About the middle of November we camped near the “Albert” silver mines, south of Witnek.

Commandant Erasmus was still in this part of the country with the remainder of the Pretoria Commando. Divided into three or four smaller groups, they watched in the neighbourhood of the railway, from Donkerhoek till close to Wilgeriver Station, and whenever the enemy moved out, the men on watch gave warning and all fled with their families and cattle into the “boschveldt” along Witnek.

It was these tactics which enabled the British Press to state that the Generals Plumer and Paget had a brilliant victory over Erasmus the previous month; for, with the exception of a few abandoned carts at Zusterhoek, they could certainly not have seen anything of Erasmus and his commando except a cloud of dust on the road from Witnek to the “boschveldt.”

I had instructions to reorganise the commandos in these regions and to see that law and order were maintained. The reorganisation was a difficult work, for the burghers were divided amongst themselves.

Some wanted a different commando, while others wanted to keep to Erasmus, who was formerly general and who had been my superior, round Ladysmith. He, one of the wealthiest and most influential burghers in the Pretoria district, did not seem inclined to carry out my instructions, and altogether he could not get accustomed to the altered conditions. I did all I could in the matter, but, so far as the Pretoria Commando was concerned, the result of my efforts was not very satisfactory. Nor did the generals who tried the same thing after me get on with the reorganisation while Erasmus remained in control as an officer. A dangerous element, which he and his clique tolerated, was formed by some families (Schalkwyk and others) who, after having surrendered to the enemy, were allowed to remain on their holdings, with their cattle, and to go on farming as if nothing had happened. They generally lived near the railway between our sentry stations and those of the enemy. These “voluntarily disarmed ones,” as we called them, had got passes from the enemy, allowing them free access to the British camps, and in accordance with one of Lord Roberts’ proclamations, their duty, on seeing any Boers or commandos, was, to notify this at once to the nearest English picket, and also to communicate all information received about the Boers. All this was on penalty of having their houses burnt down and their cattle and property confiscated. Sometimes a brother or other relative of these “hands-uppers” would call on them. The son of one of them was adjutant to Commandant Erasmus, and shared his tent with him, while the adjutant often visited his parents during the night and sometimes by day; the consequence being that the English always knew exactly what was going on in our district. This situation could not be allowed to go on, and I instructed one of my officers to have all these suspected families placed behind our commandos. Any male persons who had surrendered to the enemy out of cowardice were arrested.

Most of them were court-martialled for high treason and desertion, and giving up their arms, and fifteen were imprisoned in a school building at Rhenosterkop, which had been turned into a gaol for the purpose. The court consisted of a presiding officer selected from the commandants by the General, and of four members, two of whom had been chosen by the General and the President, and two by the burghers.

In the absence of our “Staats-procureur,” a lawyer was appointed public prosecutor.

Before the trial commenced the President was sworn by the General and the other four members by the President. The usual criminal procedure was followed, and each sentence was submitted for the General’s ratification.

The court could decree capital punishment, in which case there could be an appeal to the Government.

There were other courts, constituted by the latter, but as they were moving about almost every day, they were not always available, and recourse had then to be taken to the court-martial.

The fifteen prisoners were tried in Rhenosterkop churchyard. The trial lasted several days, and I do not remember all the particulars of the various sentences, which differed from two and a half to five years’ imprisonment, I believe with the option of a fine. The only prison we could send them to was at Pietersburg, and there they went.

The arresting and punishing of these people caused a great sensation in the different commandos.

It seems incredible, but it is a fact that many members of these traitors’ families were very indignant about my action in the matter, even sending me anonymous letters in which they threatened to shoot me.

Although there was less treason after the conviction of these fifteen worthies had taken place, there always remained an easy channel in the shape of correspondence between burghers from the commandos and their relatives within the English fighting lines, carried by kaffir runners. This could not be stopped so easily.

On the 19th of November, 1900, I attacked the enemy on the railway simultaneously at Balmoral and Wilgeriver, and soon found that the British had heard of our plan beforehand.

Commandant Muller, who was cautiously creeping up to the enemy at Wilgeriver with some of his burghers, and a Krupp gun, met with a determined resistance early in the morning. He succeeded, indeed, in taking a few small forts, but the station was too strongly fortified, and the enemy used two 15-pounders in one of the forts with such precision as to soon hit our Krupp gun, which had to be cleared out of the fighting line.

The burghers, who had taken the small forts in the early morning, were obliged to stop there till they could get away under protection of the darkness, with three men wounded. We did not find out the enemy’s losses.

We were equally unfortunate near Balmoral Station, where I personally led the attack.

At daybreak I ordered a fortress to be stormed, expecting to capture a gun, which would enable us to fire on the station from there, and then storm it. In fact we occupied the fort with little trouble, taking a captain and 32 men prisoners, besides inflicting a loss of several killed and wounded, while a score more escaped. These all belonged to the “Buffs,” the same regiment which now takes part in watching us at St. Helena. But, on the whole, we were disappointed, not finding a gun in the fort, which was situated to the west of the station. Two divisions of burghers with a 15-pounder and a pom-pom were approaching the station from north and east, while a commando, under Field-Cornet Duvenhage, which had been called upon to strengthen the attack, was to occupy an important position in the south before the enemy could take it up, for during the night it was still unoccupied.

Our 15-pounder, one of the guns we had captured from the English, fired six shells on the enemy at the station, when it burst, while the pom-pom after having sent some bombs through the station buildings, also jammed. We tried to storm over the bare ground between our position and the strongly barricaded and fortified station, and the enemy would no doubt have been forced to surrender if they had not realised that something had gone wrong with us, our guns being silent, and Field-Cornet Duvenhage and his burghers not turning up from the south. The British, who had taken an important position from which they could cover us with their fire, sent us some lyddite shells from a howitzer in the station fort. Although there was a good shower of them, yet the lyddite-squirt sent the shells at such a slow pace, that we could quietly watch them coming and get under cover in time and therefore they did very little harm.

At eight o’clock we were forced to fall back, for although we had destroyed the railway and telegraphic communications in several places over night, the latter were repaired in the afternoon, and the enemy’s reinforcements poured in from Pretoria as well as from Middelburg. I observed all this through my glass from the position I had taken up on a high point near the Douglas coal mines.

Amongst the prisoners we had made in the morning was a captain of the “Buffs,” whose collar stars had been stripped off for some reason, the marks showing they had only recently been removed. At that time there were no orders to keep officers as prisoners-of-war, and this captain was therefore sent back to Balmoral with the other “Tommies,” after we had relieved them of their weapons and other things which we were in want of. I read afterwards, in an English newspaper, that this captain had taken the stars off in order to save himself from the “cruelties of the Boers.”

This, I considered, an unjust and undeserved libel.

CHAPTER XXVI

BATTLE OF RHENOSTERKOP.

On the 27th of November, 1900, our scouts reported that a force of the enemy was marching from the direction of Pretoria, and proceeding along Zustershoek. I sent out Commandant Muller with a strong patrol, while I placed the laager in a safe position, in the ridge of kopjes running from Rhenosterkop some miles to the north. This is the place, about 15 miles to the north-east of Bronkhorst Spruit, where Colonel Anstruther with the 94th regiment was attacked in 1881 by the Boers and thoroughly defeated. Rhenosterkop is a splendid position, rising several hundred feet above the neighbouring heights, and can be seen from a great distance. Towards the south and south-east this kopje is cut off from the Kliprandts (known by the name of Suikerboschplaats) by a deep circular cleft called Rhenosterpoort.

On the opposite side of this cleft the so-called “banks” form a “plateau” about the same height as the Rhenosterkop, with some smaller plateaux, at a lesser altitude, towards the Wilge River. These plateaux form a crescent running from south-east to north of the Rhenosterkop. Only one road leading out of the “bank” near Blackwood Camp and crossing them near Goun, gives access to this crescent. On the west side is a great gap up to Zustershoek, only interrupted by some “randjes,” or ridges, near the Albert silver mines and the row of kopjes on which I had now taken up a position.

The enemy’s force had been estimated at 5,000 men, mostly mounted, who, quite against their usual tactics, charged us so soon as they noticed us. Muller had to fall back again and again. The enemy under General Paget, pursued us as if we were a lot of game, and it soon became apparent that they had made up their mind to catch us this time. I sent our carts into the forest along Poortjesnek to Roodelaager, and made a stand in the kopjes near Rhenosterkop.

On the 28th—the next day—General Paget pitched his camp near our positions, shelling us with some batteries of field guns till dusk. The same evening I received information that a force under General Lyttelton had marched from Middelburg and arrived near Blackwood Camp. This meant that our way near Gourjsberg had been cut off. All we could do was to keep the road along Poortjesnek well defended, for if the enemy were to succeed in blocking that as well, we would be in a trap and be entirely cut up.

There was General Paget against us to the west, to the south there was Rhenosterkop with no way out, and General Lyttelton to the east, while to the north there was only one road, running between high chains and deep clefts. If General Paget were to make a flanking movement threatening the road to the north, I should have been obliged to retire in hot haste, but we were in hopes the General would not think of this. General Lyttelton only needed to advance another mile, right up to the first “randts” of the mountain near Blackwood Camp, for his guns to command our whole position, and to make it impossible for us to hold it. I had, however, a field-cornet’s company between him and my burghers, with instructions to resist as long as possible, and to prevent our being attacked from behind, which plan succeeded, as luck would have it. My Krupp and pom-pom guns had been repaired, or rather, patched up, though the former had only been fired fourteen times when it was done up.

I placed the Johannesburgers on the left, the Police in the centre, and the Boksburgers on the right. As I have already pointed out, these positions were situated in a row of small kopjes strewn with big “klips,” while the assailant would have to charge over a bare “bult,” and we should not be able to see each other before they were at 60 to 150 paces distant.

Next morning, when the day dawned, the watchmen gave the alarm, the warning we knew so well, “The Khakis are coming!” The horses were all put out of range of the bullets behind the “randts.” I rode about with my officers in front of our positions, thus being able to overlook the whole ground, just at daybreak.

It gave me a turn when I suddenly saw the gigantic army of “Khakis” right in front of us, slowly approaching, in grand formation, regiment upon regiment, deploying systematically, in proper fighting order, and my anxiety was mingled with admiration at the splendid discipline of the adversary. This, then, was the first act in the bloody drama which would be played for the next fifteen hours. The enemy came straight up to us, and had obviously been carefully reconnoitring our positions.

General Paget seemed to have been spoiling for a fight, for it did not look as if he simply meant to threaten our only outlet. His heavy ordnance was in position near his camp, behind the soldiers, and was firing at us over their heads, while some 15-pounders were divided amongst the different regiments. The thought of being involved in such an unequal struggle weighed heavily on my mind. Facing me were from four to five thousand soldiers, well equipped, well disciplined, backed up by a strong artillery; just behind me my men, 500 at the outside, with some patched-up guns, almost too shaky for firing purposes.

But I could rely on at least 90 per cent. of my burghers being splendid shots, each man knowing how to economise his store of ammunition, while their hearts beat warmly for the Cause they were fighting.

The battle was opened by our Krupp gun, from which they had orders to fire the fourteen shells we had at our disposal, and then “run.” The enemy’s heavy guns soon answered from the second ridge. When it was broad daylight the enemy tried his first charge on the Johannesburg position, over which my brother had the command, and approached in skirmishing order. They charged right up to seventy paces, when our men fired for the first time, so that we could not very well have missed our aim at so short a distance, in addition to which the assailants’ outline was just showing against the sky-line as he was going over the last ridge. Only two volleys and all the Khakis were flat on the ground, some dead, others wounded, while those who had not been hit were obliged to lie down as flat as a pancake.

The enemy’s field-pieces were out of our sight behind the ridge which the enemy had to pass in charging, and they went on firing without any intermission. Half an hour later the position of the Johannesburg Police, under the late Lieutenant D. Smith, was stormed again, this time the British being assisted by two field-pieces which they had brought up with them in the ranks and which were to be used as soon as the soldiers were under fire. They came to within a hundred paces. One of these guns, I think, I saw put up, but before they could get the range it had to be removed into safety, for the attacking soldiers fared equally badly here as on our left flank.

Then, after a little hesitation, they tried the attack on our right flank again, when Commandant Muller and the Boksburgers and some Pretoria burghers, under Field-Cornet Opperman held the position, but with the same fatal result to the attackers. Our fifteen-pounder, after having been fired a few times, had given out, while our pom-pom could only be used from time to time after the artilleryman had righted it.

I had a heliograph post near the left-hand position, one near the centre and the one belonging to my staff on our extreme right. I remained near this, expecting a flank movement by General Paget after his front attacks had failed. From this coign of vantage I was able to overlook the whole of the fighting ground, besides which I was in constant touch with my officers, and could tell them all the enemy’s movements.

About 10 o’clock they charged again, and so far as I could see with a fresh regiment. We allowed them to come up very closely again and once more our deadly Mauser fire mowed them down, compelling those who went scot-free to go down flat on the ground, while during this charge some who had been obliged to drop down, now jumped up and ran away. If I remember rightly, it was during this charge that a brave officer, who had one of his legs smashed, leant on a gun or his sword, and kept on giving his orders, cheering the soldiers and telling them to charge on. While in this position, a second bullet struck him, and he fell mortally wounded. We afterwards heard it was a certain Colonel Lloyd of the West Riding Regiment. A few months after, on passing over this same battlefield, we laid a wreath of flowers on his grave, with a card, bearing the inscription: “In honour of a brave enemy.”

General Paget seemed resolved to take our positions, whatever the sacrifice of human lives might be. If he succeeded at last, at this rate, he might find half a score of wounded burghers and, if his cavalry hurried up, perhaps a number of burghers with horses in bad condition, but nothing more.

Whereas, if he had made a flanking movement, he might have attained his end, perhaps without losing a single man.

Pride or stupidity must have induced him not to change his tactics. Nothing daunted by the repeated failures in the morning, our assailant charged again, now one position and then another, trying to get their field-pieces in position, but each time without success. At their wits’ end, the enemy tried another dodge, bringing his guns right up to our position under cover of some Red Cross waggons. The officer who perceived this, reported to me by heliograph, asking for instructions. I answered: ‘If a Red Cross waggon enters the fighting lines during the battle, it is there on its own responsibility.’ Besides, General Paget, under protection of the white flag, might have asked any moment or an hour, or longer, to carry away his many unfortunate wounded, who were lying between two fires in the burning sun.

When the Red Cross waggon was found to be in the line of fire, it was put right-about face, while some guns remained behind to fire shrapnel at us from a short distance. They could only fire one or two shots, for our burghers soon put out of action the artillerists who were serving them. Towards the afternoon some of my burghers began to run short of ammunition, I had a field-cornet’s force in reserve, from which five to ten men were sent to the position from time to time, and this cheered the burghers up again.

The same attacking tactics were persisted in by General Paget all day long, although they were a complete failure. When the sun disappeared behind the Magaliesbergs, the enemy made a final, in fact, a desperate effort to take our positions, the guns booming along while we were enveloped by clouds of dust thrown up by the shells.

The soldiers charged, brave as lions, and crept closer to our positions than they had done during the day.

But it seemed as if Fate were favouring us, for our 15-pounder had just got ready, sending his shells into the enemy’s lines in rapid succession, and finding the range most beautifully. The pom-pom too—which we could only get to fire one or two shells all day long, owing to the gunner having to potter about for two or three hours after each shot to try and repair it—to our great surprise suddenly commenced booming away, and the two pieces—I was going to say the “mysterious” pieces—poured a stream of murderous steel into the assailants, which made them waver and then retire, leaving many comrades behind.

On our side only two burghers were killed, while 22 were wounded. The exact loss of the enemy was difficult to estimate. It must, however, have amounted to some hundreds.

Again night spread a dark veil over one of the most bloody dramas of this war. After the cessation of hostilities, I called my officers together and considered our position. We had not lost an inch of ground that day, while the enemy had gained nothing. On the contrary, they had suffered a serious repulse at our hands. But our ammunition was getting scarce, our waggons, with provisions, were 18 miles away. All we had in our positions was mealies and raw meat, and the burghers had no chance of cooking them. We therefore decided, as we had no particular interest in keeping these positions, to fall back that night on Poortjesnek, which was a “half-way house” between the place we were leaving and our carts, from which we should be able to draw our provisions and reserve ammunition.

We therefore allowed General Paget to occupy these positions without more ado.

I have tried to describe this battle as minutely as possible in order to show that incompetence of generals was not always on our side only.

I have seen from the report of the British Commander-in-Chief, published in the newspapers, that this battle had been a most successful and brilliant victory, gained by General Paget. People will say, perhaps, that it was silly on my part to evacuate the positions, and that I should have gone on defending them the next day. Well, in the old days this would have been done by European generals, but no doubt they were fighting under different circumstances. They were not faced by a force ten times their own strength; not restricted to a limited quantity of ammunition; nor were they in want of proper food or reinforcements. The nearest Boer commando was at Warmbad, about 60 miles distant. Besides, there was no necessity, either for military or strategical reasons, for us to cling to these positions. It had already become our policy to fight whenever we could, and to retire when we could not hold on any longer. The Government had decided that the War should be continued and it was the duty of every general to manœuvre so as to prolong it. We had no reserve troops, so my motto was: “Kill as many of the enemy as you possibly can, but see you do not expose your own men, for we cannot spare a single one.”

On the 30th of November, the day after the fight, I was with a patrol on the first “randts,” north-east of Rhenosterkop, just as the sun rose, and had a splendid view of the whole battlefield of the previous day. I saw the enemy’s scouts, cautiously approaching the evacuated positions, and concluded from the precautions they were taking that they did not know we had left overnight. Indeed, very shortly after I saw the Khakis storming and occupying the kopjes. How great must have been their astonishment and disappointment on finding those positions deserted, for the possession of which they had shed so much blood. A number of ambulance waggons were brought up and were moving backwards and forwards on the battlefield, taking the wounded to the hospital camp, which must have assumed colossal proportions. Ditches were seen to be dug, in which the killed soldiers were buried. A troop of kaffirs carried the bodies, as far as I could distinguish, and I could distinctly see some heaps of khaki-coloured forms near the graves.

As the battlefield looked now, it was a sad spectacle. Death and mutilation, sorrow and misery, were the traces yesterday’s fight had left behind. How sad, I thought, that civilised nations should thus try to annihilate one another. The repeated brave charges made by General Paget’s soldiers, notwithstanding our deadly fire, had won our greatest admiration for the enemy, and many a burgher sighed even during the battle. What a pity such plucky fellows should have to be led on to destruction like so many sheep to the butcher’s block!

Meanwhile, General Lyttelton’s columns had not got any nearer, and it appeared to us that he had only made a display to confuse us, and with the object of inducing us to flee in face of their overwhelming strength.

On the 1st of December General Paget sent a strong mounted force to meet us, and we had a short, sharp fight, without very great loss on either side.

This column camped at Langkloof, near our positions, compelling us to graze and water our horses at the bottom of the “neck” in the woods, where horse-sickness was prevalent. We were, therefore, very soon obliged to move.