Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Historic Events of Colonial Days, by Rupert S. Holland (published 1916).

Peter Stuyvesant saw that he would have to make terms with the English Captain Scott, or more English adventurers might come swarming down from New England and speedily gobble up the whole of Manhattan Island. He went to Hempstead on Long Island, on the third day of March, 1664, and made an agreement with Scott that the villages on the western part of the island, where the settlers were mainly English, should consider themselves under English rule until the whole dispute could be settled by King Charles and the Dutch government. The Dutch had now lost bit by bit most of the colony they had started out to settle. First the English had taken the valley of the Connecticut River, because there were more English settlers there than Dutch, then they took Westchester, now the four important villages of Flushing, Jamaica, Hempstead and Gravesend were added to their list.

Meantime the States-General of Holland, receiving appeals for help from Stuyvesant, sent him sixty soldiers, and ordered him to resist any further demands of the English and to try to make the villages that had rebelled return again to his flag. But the governor knew that he could not possibly do this, his people were outnumbered six to one, and while he was turning this matter over in his mind news came that the English people in Connecticut were making a treaty of alliance with the Indians who lived along the Hudson. Fearful lest all the tribes should side with his rivals, Stuyvesant invited a number of the Indian chiefs to a meeting at the fort of New Amsterdam.

The chiefs came to the council. One of them called upon Bachtamo, their tribal name for the Great Spirit, to hear him. “Oh, Bachtamo,” he said, “help us to make a good treaty with the Dutch. And may the treaty we are about to make be like the stick I hold in my hand. Like this stick may it be firmly united, the one end to the other.”

Then turning to Stuyvesant and his officers, he went on, “We all desire peace. I have come with my brother sachems, in behalf of the Esopus Indians, to conclude a peace as firm and compact as my arms, which I now fold together.”

He held out his hand to the governor. “What I now say is from the fullness of my heart. Such is my desire, and that of all my people.”

A treaty was drawn up, signed by the Dutch and the Indians, and celebrated by the firing of cannon from the fort. Stuyvesant proclaimed a day of general thanksgiving in honor of the new alliance with the Indians.

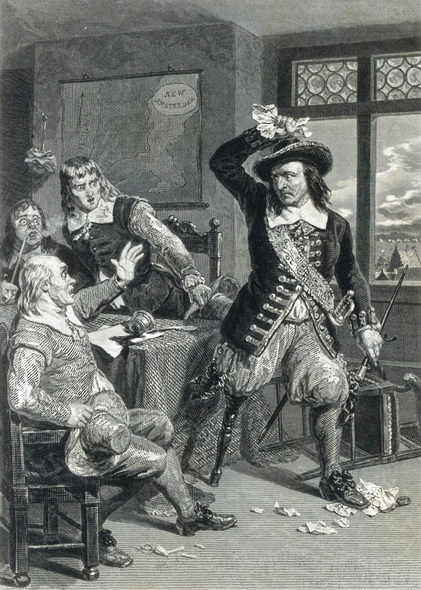

Now it had been supposed that the English towns on Long Island would join the colony of Connecticut, but instead the settlers proclaimed their own independence and chose John Scott for their president. Then the court at Hartford sent John Allyn, with a party of soldiers, to arrest Captain Scott for treason. Scott met the Connecticut soldiers with soldiers of his own, and demanded what they wanted on his land. The Connecticut officer read the order for Scott’s arrest. Then said Captain Scott, “I will yield my heart’s blood on this ground before I will give in to you or any men from Connecticut!” The men from Hartford answered readily, “So will we!”

But in spite of his bold words his opponents did succeed in arresting Scott, and, taking him to Hartford, put him in prison there. Governor Winthrop went to Long Island to appoint new officers in the English villages in place of Scott’s men, and Stuyvesant seized the chance to go to meet the Connecticut governor and make some treaty with him. The governor of New Netherland explained to the governor of the Connecticut Colony that the Dutch claimed the land they occupied by the rights of discovery, purchase, and possession, and reminded him that the boundary between the two colonies had been defined in a treaty made in 1650. Said that treaty, “Upon Long Island a line run from the westernmost part of Oyster Bay, in a straight and direct line to the sea, shall be the bounds between the English and the Dutch there; the easterly part to belong to the English, the westernmost part to the Dutch.”

Yet, in spite of this, Governor Winthrop was now many miles west of the line, claiming villages that were clearly in Dutch territory. The truth was that Governor Winthrop knew Peter Stuyvesant had not the needful number of men to oppose the English claims. And the upshot of the meeting was that Winthrop simply declared that the whole of Long Island belonged to the king of England.

That king of England, Charles II, now took a hand in the matter himself. On March 12, 1664, he granted to his brother, James, Duke of York, the whole of Long Island, all the islands near it, and all the lands and rivers from the west shore of the Connecticut River to the east shore of Delaware Bay. It was a wide, magnificent grant, sweeping away the colony of New Netherland as if it had been a twig in the path of a tornado.

Word reached New Amsterdam that a fleet of armed ships had sailed from Portsmouth in England, bound for the Hudson River, to take possession of the neighboring territory. The prosperous Dutch settlers were in a panic. Peter Stuyvesant called his council, and they decided to lose no time in making their fortifications as strong as possible. Money was raised, powder was sent for, agents hurried to buy provisions all through the countryside. In the midst of these preparations the Dutch government, which had been completely fooled as to the plans of the English king, sent a message to Governor Stuyvesant saying that he need have no fear of any further trouble from the English.

This was pleasant word; it relieved the fears that had been raised by the message of the armed fleet sailing from Portsmouth for the Hudson. The work on the forts was stopped, and Stuyvesant went up the river to Fort Orange to try to quiet Indian tribes in that neighborhood who were threatening to take to the war-path.

The English fleet, four frigates, with ninety-four guns all told, meantime came sailing across the Atlantic, and arrived at Boston the end of July. Colonel Richard Nicholls was in command of the expedition, with three commissioners sent out with him from England. Their instructions were to reduce the Dutch to subjection. They were to get what aid they could from the New England colonies. The people of Boston, however, were too busy with their own affairs, and too content, to be interested in helping to fight the Dutch. But Connecticut was quite ready to help, and so Colonel Nicholls sent word to Governor Winthrop to meet the English fleet at the west end of Long Island, to which place it would sail with the first favoring wind.

A friend of Peter Stuyvesant’s in Boston sent news of the English plans to New Amsterdam. A fast rider carried the message to the governor at Fort Orange. Stuyvesant hastened back to his capital, very angry at having lost three weeks in which to make ready his defenses. He called every man to work with spade, shovel and wheelbarrow. Six cannon were added to the fourteen already on the fort. Messengers rode through the country summoning other garrisons to come to the aid of New Amsterdam.

On August 20th the English frigates anchored in Nyack Bay, just below the Narrows, between New Utrecht and Coney Island. All communication between Long Island and Manhattan Island was cut off. Some small Dutch boats were captured. Three miles away from the fleet’s anchorage, on Staten Island, was a small fort, a block-house, some twenty feet square. It boasted two small guns, which shot one pound balls, and was garrisoned by six soldiers. The English, sending some of their men ashore, had little difficulty in capturing the fort and rounding up the cattle that were grazing in the near-by fields.

The morning after he dropped anchor Colonel Nicholls despatched four of his men to Fort Amsterdam on Manhattan Island, with a summons to the garrison to surrender. At the same time he sent out word that if any of the farmers furnished supplies to the fort he would burn their houses, but that if they would quietly acknowledge the English flag they might keep their farms in peace.

Now Peter Stuyvesant had only one hundred soldiers in his garrison, and he could not hope for much real aid from the other men, undisciplined and poorly armed as they were, who lived on Manhattan Island. But he meant to resist these invaders as strongly as he was able, and so called his council together to consider what they might do for defense.

The peace-loving Dutch citizens, however, lacked the fiery spirit of their governor, and they too held a meeting, and voted not to resist the English fleet, and asked for a copy of the demand to surrender that Nicholls had sent to the fort. Governor Stuyvesant, angry though he was, went to the citizens and tried to persuade them to stand by him. But the citizens, fearful that a bombardment would destroy their little settlement, were not in the humor to agree with his ideas.

The English commander sent another envoy, with a flag of truce, to Fort Amsterdam, carrying a letter which stated that if Manhattan Island was surrendered to him the Dutch settlers might keep all the lands and buildings they possessed. Stuyvesant received the letter, and read it to his council. The council insisted that the letter should be read to the people. Stuyvesant refused, saying that he, and not the people, was the best judge as to what New Amsterdam should do. The council continued to argue and threaten, until Stuyvesant tore up the letter and trampled it under his feet to settle the matter.

The citizens, however, had heard that such a letter had come with a flag of truce, and they sent three men to demand the message from Peter Stuyvesant. These men told him bluntly that the people did not intend to resist the English, that resistance to such a large force was madness, and that they would mutiny unless he let them see the letter Colonel Nicholls had sent.

Again Governor Stuyvesant was forced to yield to pressure. A copy was made of the letter from its torn pieces, and this was read to the turbulent citizens. When they had heard it they declared that they were ready to surrender. But the governor hated the notion of giving up his province of New Netherland without a struggle; of yielding to highway robbers, as he regarded the English fleet. So he sent a ship secretly from Fort Amsterdam by night, bearing a message to the directors of the Dutch Company in Europe. The message was short. “Long Island is gone and lost. The capitol cannot hold out long,” was what it said.

Then he sat down and wrote an answer to the letter of Colonel Nicholls. It was a fair-spoken answer, pointing out that this land belonged to the Dutch by right of discovery and settlement and purchase from the Indians. He said that he was sure the king of England would agree with the Dutch claims if they were presented to him. This was the end of his letter: “In case you will act by force of arms, we protest before God and man that you will perform an act of unjust violence. You will violate the articles of peace solemnly ratified by His Majesty of England, and my Lords the States-General. Again for the prevention of the spilling of innocent blood, not only here but in Europe, we offer you a treaty by our deputies. As regards your threats we have no answer to make, only that we fear nothing but what God may lay upon us. All things are at His disposal, and we can be preserved by Him with small forces as well as by a great army.”

The only answer the English commander saw fit to make to the Dutch governor’s letter was to order his soldiers to prepare to land from the frigates.