As a child, I often wandered around the 3-story brownstone mansion (so it seemed to me) of my grandparents. Memory renders it a mythical place, set at the end of a winding road at the top of a hill, with rough flagstone paths, a small fountain and goldfish pond, terraced yards with rock walls, flowerpots, and garden patches. The back yard rolled down a small hill to a semicircle communal garden shared by several other upper-middle-class houses, with a long, arbored walkway set in geometrically arranged flower gardens. You could imagine an F. Scott Fitzgerald character spending a Sunday afternoon there.

I remember once, years later, happening upon a small nook in the house that held my gaze. There was a bookshelf with old bound volumes of Cicero and Homer, English poets, novelists, theologians, and historians. There was an oval rug, a floor lamp casting a pool of light, and a spindled wooden armchair from which to peruse these volumes. In spite of the plain objects, there was a harmony in the layout that made it fresh, yet centuries old, and induced a certain reverence as I sat there and began to read.

The Eyes Have It

The spaces we choose to inhabit reveal much about what’s in our souls. Not necessarily their moral condition, but absolutely their morale. A culture’s architecture might not explain whether a people run to good or evil according to traditional Christian values, but it does tell us whether they have aspirations, and whether they accord significance to life and one’s place in the world. Take a look at this video from above the cloud layer in Dubai, a sci-fi city worthy of a boy’s dreams:

Yes, down in the street bustle of Dubai, there is sure to be squalor in places, and we of the West know at least something of the repressive and intolerant nature of Muslim society. But we see something here that is missing from our modern cities. There is wonder. There is dedication. There is a sense of future, but absolutely connected to the past: a thing we used to call “destiny”. There is respect for order and beauty. And there is purpose. Not just competing individual aspirations, but shared purpose and resolve. You could also bring up words like “dignity,” “stateliness,” and “grandeur,” but in our time to use these words is to invoke a wince, a laugh, or even outright mockery. Why should that be?

America’s cities, and most cities of the West, gave up something important during that period from the 1920s to the 1970s: significance. Nothing can be significant if it is disconnected from the past or the future, or from that which inspires a people. Seemingly overnight, civic spaces became dominated by rectangular, thoughtless boxes, or weird shapes (usually just odd combinations of rectangles and other primitives) with almost no sense of scale in relation to the humans who were to inhabit them. Modernism began its steady progress over the landscape. “Do away with all that is sentimental or derivative!”, designers were admonished. It was time for humans to step into the cold light of reason and utility. Why have cornices or friezes or plinths, or be concerned with Doric and Ionic order? Unnecessary! Why elaborate on the spaces in any way? Let doors and walls be flat. Let a building be perforated by one hundred or two hundred windows of exactly the same size and spacing! Yes, all four walls will be identical! Functional is the only form of beauty we need. Form follows function, or it should be tossed out. People should have stark reality shoved in their faces. Now, of course, the concept was not to do away with the aesthetic, but to radically alter the concept of what is aesthetic.

Could there be any more eloquent metaphor for modernism’s relationship to history than what this architect added to the Bundeswehr Museum of Military History in Dresden? Cleft through, with complete disregard for what came before.

Modernism is History

The roots of the modernist architectural movement reach back to the 1920s and 30s, with what became known as the International Style. Note that intrinsic to the name is the implication that a sense of place would be lost. Choose a modern building in Brussels, and it could as easily exist in San Francisco or Rio de Janeiro. Do a Google image search for “architecture international style” and you would be hard-pressed to find any example of a building that offers cues as to its country without relying on the name of the building or the background scenery. There is a reason for this. There is a mindset behind it, and it does reveal something about the souls of those responsible. Note the social changes taking place among the intelligentsia of the West during that time. Humanism and her sibling, socialism, were becoming all the rage. Old ideas were being cast out, and the fires of revolution were rising. Even the United States came (some say) within a hair’s breadth of becoming a full socialist state during those tumultuous times. A particular sort of arrogance was burgeoning. It was an arrogance of the mind. Reason was going to take us away from primitive slavery to ritual and folk mores. All of the foolishness of mankind could be dealt with if one just… structured society properly. From the extremes of Marx and Stalin to the moderate progressivism of US Presidents Wilson or FDR, this theme was central. The rationality of this mindset is something to be explored in future articles, but our intent at present is to look upon the outward appearance, for it does provide us some eloquent clues.

You could say modern architecture was a rational response to a culture that had become mired in middle class sentimentality, hokey tradition and folksy mores, following meaningless ritual without question. In America, the culture of “Leave it to Beaver” and “The Andy Griffith Show” were sure to invite a lip curl by any thinking man. There was some rationale for this disdain. Increasingly architectural themes in use were merely cake decorations applied onto the exterior of a building with a pretense of following traditional forms, but without the function that had originally brought those forms about, like faux columns that no longer supported weight. This frustration spurred a valid cause—inject fresh ideas and vigor into the public sphere. You could also say that it was a response to the obdurate march of technology and human progress. New building materials, new engineering methods, efficiency, automation, and the higher cost of labor all led naturally to doing things a different way.

But it was more than that. The Modernists had decided it was time to shake things up in the human being himself. Traditionally, art and architecture has been seen as a reflection of the surrounding culture. They decided it was time for artists to drive the culture. It is not a completely new idea, as the Romantics of the previous century had similar ambitions, but the Modernists set about the task in earnest, aiming for far more sweeping changes, and coordinating their attack with philosophers, politicians, writers, educators, aligning resources so that decade after decade, a slow tide worked its effect. This began in the writing and the fine arts, and but quickly proceeded to design and structure, to affect our very surroundings. The purpose was indeed to mold minds, to create a new human being.

If one wants to taste the cerebral soup that led to these things, one must probably start with Rousseau, but quickly move forward to the thinkers that lived within his intellectual heritage: an endless list including Karl Marx, Sartre, Bertrand Russell, John Dewey and Derrida. One thing you will find in common with all of these people is a rejection of religion (and of course specifically Christianity) as a central element in culture. And, a furious determination to rework Western culture towards other ends. Rationalism, socialism, pragmatism, objectivism, and communism: all were manifestations in one way or another.

In All Seriousness

Whole libraries have been written on how the modernists tried to reinterpret art and aesthetics. To dip into them is to suffuse oneself in soul-killing, excruciatingly abstruse terminology and phrasing. Words like phenomenology, structuralism, post-structuralism, reification, deconstructivism, etc… Gone are the direct, descriptive, vivid words of history. Everything became an -ism or an -ology or an -ition or an -ation. Whereas in previous centuries the written word tried to edify the soul when discussing art, now the attempt was to ruthlessly dissect the soul, and perhaps replace it with a system of gears and levers. Compare this sentence in John Dewey’s “Art as Experience”:

The task is to restore continuity between the refined and intensified forms of experience that are works of art and the everyday events, doings, and sufferings that are universally recognized to constitute experience.

To these quotes by John Ruskin (1819 – 1900):

All great art is the expression of man’s delight in God’s work, not his own.

——

Nobody cares much at heart about Titian, only there is a strange undercurrent of everlasting murmur about his name, which means the deep consent of all great men that he is greater than they.

——

All that is good in art is the expression of one soul talking to another, and is precious according to the greatness of the soul that utters it.

Which of these gives you more of a passion for truth and beauty? Ruskin speaks with directness and conviction, while… regard in Dewey the dry monotone dreariness, the dispassionate analysis. Trust us, it gets far worse if you read further. And Dewey was by no means the most tedious (just read Derrida). This meticulous jargon-driven newspeak of art philosophy drove common people away from these intellectuals even as they claimed their very purpose was to bring down the high strata of “fine arts” to the level where all could enjoy them.

Where We Have Arrived

But bring down the strata they did. Now we live in an age where “The Vagina Monologues” is seriously attended by the very same people who will go to the opera. An age where a “performance art” exhibit might require the artist to insert paint in his rectum and then splatter the canvas. And his audience might just attend a performance by the Philadelphia Philharmonic the next weekend. Or, these patrons could go to the theater and witness a play where everyone is naked while pretending to be fully clothed. What was high was brought low, but still not to the common people. Common people tend to resist the machinations of the intellectuals who want to mold them, possibly the saving grace of Western civilization.

A perfect depiction of what has happened to our language (and thus to our minds and souls) is an example heard decades ago from a radio interview with a writer (whose name is unfortunately lost to memory):

After World War I, men were said to be “shell-shocked” from their experiences, as it was hard for them to resume a normal life. After World War II, the condition was redefined as “battle fatigue” (note already the drift away from the visceral and descriptive?) By the time veterans were coming home from Vietnam, the term had become “post-traumatic stress disorder.”

How very, very abstract and technical. The experts were now in charge. You could say Western Culture was in the throes of death by expert, in their fierce attempt to suck the joy out of everything.

What does all this have to do with modern architecture? Well, sucking the joy out of everything, for starters. It’s not that all modern architecture does this. One can always find brilliant examples that speak to the soul. The Sydney Opera House, or “Falling Water” by Frank Lloyd Wright come to mind instantly. But peruse the thousands of square miles of modern city dominated by slabs of reflective glass or gray concrete, dotted by the few bizarre celebrated master works that make one seriously regret visiting the city, and you get the idea:

Institutionalized Ugliness

In the postmodern era of the West, architecture exists on 4 levels:

1. Highbrow works, often meant to be “challenging” and “transgressive”, essentially pieces of modern abstract art. Sometimes deliberately counterproductive to what people might want to do with a building, they seem to exist mainly to let us know what simpletons we are, or to give us the uncomfortable feeling that we are being pranked. The middle class is to be ridiculed at every turn, and their dollars collected just as avidly.

2. The low-brow, with shapes that are silly, trivial, even garish in their artless attempts to separate us from our dollars: convenience stores, strip malls, gas stations. Drive through the tourist areas of Orlando, FL and you will end up with eye fatigue from the constant struggle for your attention. However, this level is worthy of Douglas Adams’ “Mostly Harmless” appellation, for at least here there is no pretense, and no attempt to rewrite human consciousness. America’s business culture has always had an aspect of the carnival barker.

3. Only middle-brow architecture seeks to preserve some connection to tradition and human scale. However, it accomplishes this with pasted-on decorations, faux pillars, and artificial wood grains. And even the overall shapes themselves are greatly simplified. Watered-down culture, diluted so that only a faint essence remains. But at least there is the attempt to connect with human experience, lacking in the other two.

4. And that fourth level? It is grim acceptance of our fate, giving up on any attempt or even pretense at aesthetics. Public schools, office buildings, government bureaus, apartment buildings, post offices… institutionalized drabbery, the dreaded “design by committee”, and by budget. Of course, often accompanied by horrid modern abstract art and sculptures. The highbrow even tried to invade this sphere, with the architecture of Brutalism. Yes, they called it that. And of course it was a favorite for government offices everywhere. One could even think they were trying to tell us something.

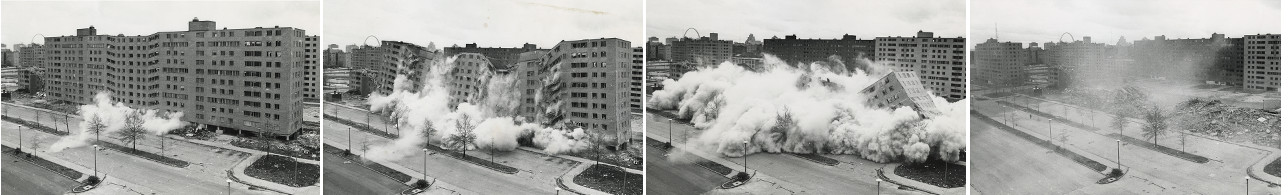

If Modernism was the era of cold determinism; postmodernism is the era of chaos and defeat. Some historians mark the death of Modernism as the demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe urban housing project (see Paul Johnson’s “Modern Times: the World from the Twenties to the Nineties“). It had been held as one of the most ambitious attempts to cement (one could say… literally) the power of modernist rational thinking with the hopes of humanism and socialism. Constructed in the early 1950s, it was composed of 33 massive buildings, 11 stories each, on 57 acres in St. Louis, Missouri. Just take a moment to regard this long-disappeared collection of concrete monoliths:

Maybe Stonehenge was the inspiration, but Stonehenge exhibits rather more charm and personality.

The creators and civic leaders who commissioned this work expected that former ghetto residents and other impoverished people would be overjoyed to move into these modern “machines for living”, in which everything was so bright and clean and new, and all angles had been reduced to right angles. But unfortunate reality had other plans. No one wanted to live there. After struggling for two decades to fill even a fraction of the dwellings, the buildings were demolished with explosives in the mid-70s, and America moved on, slightly the worse for wear.

Ego and Narcissism

Some of the most celebrated architects have demonstrated amazing contempt for their clients: buildings that force one to stand awkwardly in barren spaces, or sit on benches with straight backs, buildings that mock the very people who are intended to use them. Buildings which “challenge” the inhabitants by having stairs without railings, or rough edges in highly-trafficked areas. These are all things you will see at the top social strata of architectural design. Note the prison-like design of the Bahaus building. Sure, it has a certain geometrical distinction, but who would actually want to live or work there? The modernist laughs at anyone who would be so gauche as to voice that question.

that mock the very people who are intended to use them. Buildings which “challenge” the inhabitants by having stairs without railings, or rough edges in highly-trafficked areas. These are all things you will see at the top social strata of architectural design. Note the prison-like design of the Bahaus building. Sure, it has a certain geometrical distinction, but who would actually want to live or work there? The modernist laughs at anyone who would be so gauche as to voice that question.

The modernists at once tried to elevate man to the highest heights of narcissism, and rob him of dignity and purpose. And when modernism gave way to postmodernism, the effect was to remove order and logic as well. After all, why should things make sense if our very existence doesn’t make sense? This led to literal celebrations of ugliness, as you would see buildings with exposed ductwork, or sections purposely left to look unfinished.

To be clear, this story is not just of Architects with a capital ‘A’, because there are few actual architects. Most buildings are done without serious architectural intent. But, they still reflect the ethos of the age, and the education to which their creators were subjected. City planners, civic engineers, politicians, developers, designers, interior decorators, landscapers, construction companies–all play a part in these things. What has been wrought in the imaginations of man manifests in concrete, steel, plaster, and plastic. Look around, next time you drive through a city, and think about this.

It’s not just a question of wealth or technological capability. Modest towns can display amazing beauty and charm (such as this Alpine village). And the locus of wealth in the modern world can look like this (I challenge you to find a single attractive building in the whole Manhattan panorama, with the possible exception of the Empire State building). It’s not just a question of brains or talent. Some of the most intelligent people in the world have commissioned and built structures like this:

Perhaps an attempt at austere grandeur, but it comes across more as a stack of pallets smelling of fish waiting by the loading ramp. Compare with the masterworks of yesteryear by Palladio:

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 License.

What to do now? How about re-evaluating not just how we build things but why? How about taking a look at what makes an English country cottage or a centuries-old Bavarian village so charming, what makes an old church so sobering, what makes a classically designed museum so elevating, and finding a way to preserve something of that for our time? And let’s not succumb to the modernist argument that we “don’t want to rehash the past.” There have been many periods of architecture in the history of the West, and each has managed to preserve elements of history and classical design theory while remaining relevant and reflective of its time, people and place. We can look back through literally two and a half millennia of Western, each with its distinct flavor, yet each with remarkable beauty, attention to human scale and divine inspiration. Why should we be so ready to give all that up in one short century?

Photo taken by Wolfgang Moroder. CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Out of the Abundance of the Heart, the Mouth Speaks

Some will argue that I am not giving modern architecture a fair shake: I am not rightly dividing between the true masters and the cheap imitators, nor giving full voice to all the many reasons for the changes. Yes, there are many exceptions and fine distinctions to be made. This is not the place for that. The broad strokes are there, plain for all to see. This is no fatuous plea for a mythical golden yesteryear. These things affect us directly. We imbue our surroundings, but our surroundings imbue us, especially our children.

Recently there were two studies showing that people experience a greater sense of well-being and purpose when surrounded by classical architecture:

- Classical architecture makes us happy. So why not build more of it?

- Beautiful urban architecture boosts health as much as green spaces

There is a reason for the unnecessary harmony, intricacy and elaboration of classical architecture. It came about from centuries of careful study in what partakes of and inspires us to greatness. Not personal ambition, but greatness that reaches beyond one person’s life span. The shapes and features of classical architecture, or its many Western derivatives all fueled something in the soul, and to do away with them in a single stroke is to lose that inspiration.

The West currently sits on a nexus of great change. All the great expectations and assumptions of the modern age are crashing down, one by one. Globalism, socialism, multiculturalism, humanism–these are all things that pertain to the Modernist movement, and were already being lampooned, albeit ineffectually, by the Postmodernist movement. The postmodernist has no answer. We men of the West point to an answer. It lies in the past. It is not a past to be disparaged and discarded, nor copied as a cargo cult, but to be revived, studied, and made applicable to our age. And it requires us to think of man in his rightful place, as neither ruler of the universe nor mere cluster of atoms in temporary coordination, but made in the image of God.

This is a beautiful commentary on modernism, post modernism and their roots, as well as the corrosive effect hey have had upon art and architecture. Thank God for the simple man that sees through this foolishness.

5

4.5

I despise Dewey. Excellent article.

The absence of Christian classical education with a comprehension of the need for understanding the nature of what has been created while seeking the affirmation of a Creator has left a void where only humanity remains.

The worship and adoration of humanity has worked to not only diminished the ambition to touch the Divine, those who adhere to worship of humanity have decided that we are, in our primal form, the very embodiment of the Divine and therefore, there is no longer any desire to aspire beyond self-imposed limits. Unfortunately, those who reject God have increased in their numbers and delivered a mind-numbing pursuit of industry over inspiration.

Well done.

I believe the comment on the morphing of the term ” shell shocked” was from a George Carlin routine.

In his “Beacon Lights of History” (1902), John Lord writes of architecture:

“Painting and sculpture are the exclusive ornaments and possession of the rich and favored. But architecture concerns all men, and most men have something to do with it in the course of their lives. What boots it that a man pays two thousand pounds for a picture to be shut up in his library, and probably more valued for its rarity, or from the caprices of fashion, than for its real merits? But it is something when a nation pays a million for a ridiculous building, without regard to the object for which it is intended, to be observed and criticised by everybody and for succeeding generations. A good picture is the admiration of a few; a magnificent edifice is the pride of thousands. A picture necessarily cultivates the taste of a family circle; a public edifice educates the minds of millions. Even the Moses of Michelangelo is a mere object of interest to those who visit the church of San Pietro in Vincoli; but St. Peter’s is a monument to be seen by large populations from generation to generation. All London contemplates St. Paul’s Church or the Palace of Westminster, but the National Gallery may be visited by a small fraction of the people only once a year. Of the thousands who stand before the Tuileries or the Madeleine not one in a hundred has visited the gallery of the Louvre. What material works of man so grand as those hoary monuments of piety or pride erected three thousand years ago, and still magnificent in their very ruins! How imposing are the pyramids, the Coliseum, and the Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages! And even when architecture does not rear vaulted roofs and arches and pinnacles, or tower to dazzling heights, or inspire reverential awe from the associations which cluster around it, how interesting are even its minor triumphs! Who does not stop to admire a beautiful window, or porch, or portico? Who does not criticise his neighbor’s house, its proportions, its general effect, its adaptation to the uses designed? Architecture never wearies us, for its wonders are inexhaustible; they appeal to the common eye, and have reference to the necessities of man, and sometimes express the consecrated sentiments of an age or a nation. Nor can it be prostituted, like painting and sculpture; it never corrupts the mind, and sometimes inspires it; and if it makes an appeal to the senses or the imagination, it is to kindle perceptions of the severe beauty of geometrical forms.

Whoever, then, has done anything in architecture has contributed to the necessities of man, and stimulated an admiration for what is venerable and magnificent.”

[…] and those who are planning for the long term. We see this evident in everything from pop culture to architecture. Perhaps much of this is exacerbated by the differences in generational thinking. That would be […]

[…] and those who are planning for the long term. We see this evident in everything from pop culture to architecture. Perhaps much of this is exacerbated by the differences in generational thinking. That would be […]

[…] are surrounded by decay on all sides. Our buildings are purposely ugly. The family is broken. our nation is broke. Our televisions dump sewage onto our bedroom floors. […]

5