Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Heroes of the Indian Empire, by Ernest Foster (published 1886).

“How soon could you start for India?” was the question put to Sir Colin Campbell by Lord Panmure, the Secretary at War, on Saturday afternoon, July 11th, 1857. For the startling news had just been received from the East that not only was the Mutiny spreading, but that the Commander-in-Chief, General Anson, had fallen a victim to cholera.

“This evening, if necessary,” was the prompt reply. And on the next day Sir Colin, appointed General Anson’s successor, was speeding towards Calcutta.

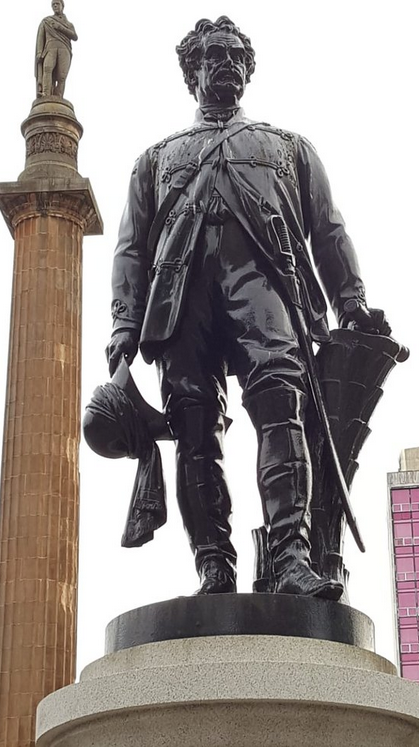

A right gallant old soldier was he, who, responding to duty’s call, thus went forth to serve his Queen and country in the hour of need. Sixty-five years of age, his life for close on half a century had been nearly all spent amid the din of arms. Born in Glasgow on the 20th of October, 1792, he entered the army in 1808, and within three months was promoted to a lieutenancy, and saw active service in the Peninsula. This was at Vimiera, where the Duke of Wellington, then Sir Arthur Wellesley, defeated the French. It was here, we are told, that just as the battle began, Colin’s captain suddenly called him to his side, and, taking his hand, led him to the front, in view of the enemy’s fire, where he walked him up and down for several minutes to try his nerve and inspire him with confidence. He then let him go, and, his object attained, bade him rejoin his regiment.

Later on the young officer served under Sir John Moore, and, along with Sir Charles Napier, was present at the retreat on Corunna; and it was his regiment that had the sorrowful honour of preparing the grave on the ramparts, where, “at dead of night,” their brave chief was silently laid to rest. Among other places in the Peninsula at which he played a distinguished part was San Sebastian, where he led the storming party. Here he was first shot through the hip, in consequence of which he fell down the breach; and next, on rushing forward again, he received a dangerous wound in the thigh. He gained high commendation for his courage during this campaign, and by the time he was twenty-one he was made captain. Nova Scotia saw him next; after which he served in the West Indies; then in England; until in 1841, then lieutenant-colonel, he saw service in China, and was made a Companion of the Bath. Six years later he drew sword for the first time on Indian soil; and at Chillianwalla and Goojerat, during the Sikh war, he so distinguished himself that in recognition of his services he was made a Knight Commander of the Bath.

Then a few years later, after other important services, came an eventful period in his career. In 1854, in command of the Highland Brigade, Major General Sir Colin Campbell was called to the Crimea. At the battle of the Alma he took a most prominent part; and he and his gallant Highlanders not only routed the enemy, but created terror by their very presence. Then came Balaclava, where Sir Colin’s duty was to defend the British landing-place; and here it was that, contrary to the usual custom, instead of meeting the rush of the enemy’s cavalry by forming a square, he arranged his force in an unbroken even line. Just before the battle, addressing the men as they stood all in readiness, he said, “Remember, now, there is no retreat for you; you must die where you stand.” And then came the answer, with a cheer, “Ay, ay, Sir Colin, we’ll do that!” But they did not fall; for as the Russian hordes swept down on them, the immortal “Thin Red Line” (so called from the colour of their coats) greeted the enemy with such a deluge of fire that those who were not shot down were glad to fly. When, later on, he found that an officer, General Sir William Codrington, who was his junior, was appointed Commander-in Chief, Sir Colin felt so indignant at the slight put upon him that his resignation followed, and he returned to England. He was, however, asked by the Queen to return to the Crimea, and he did so; it is said, indeed, that when he went to Windsor her Majesty was so gracious to him that he told her he was ready to go back and serve under a corporal if she wished it! For his many services in this campaign, Sir Colin received the Grand Cross of the Bath; and, on his coming back to England, on the conclusion of peace, he found himself lionised by his admiring countrymen. Nor could this be wondered at. He had in every way proved himself a real hero, and his achievements had been such as appealed directly to the hearts of the people. “He was,” says one writer, “a man who, like Sir Charles Napier, could not help loving war for its own sake, even while he knew its horrors; a man whose heart beat stronger on the day of battle; a general who could inspire his soldiers with his own spirit, because while he harangued them the glow on his cheek and the tremour of his voice told how strongly his own nature was stirred.”

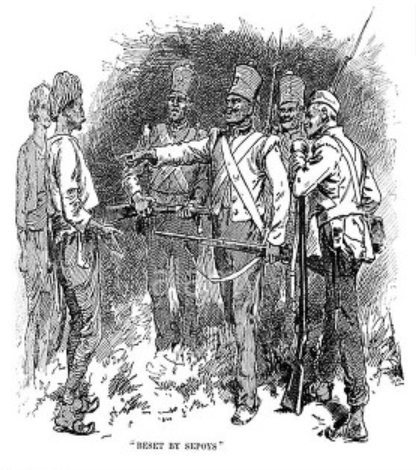

Such was the soldier who, in the serious emergency caused by the Sepoy Revolt, was regarded as the one of all others capable of stemming the tide of disaster; nor, as events proved, could more fitting choice have been made.

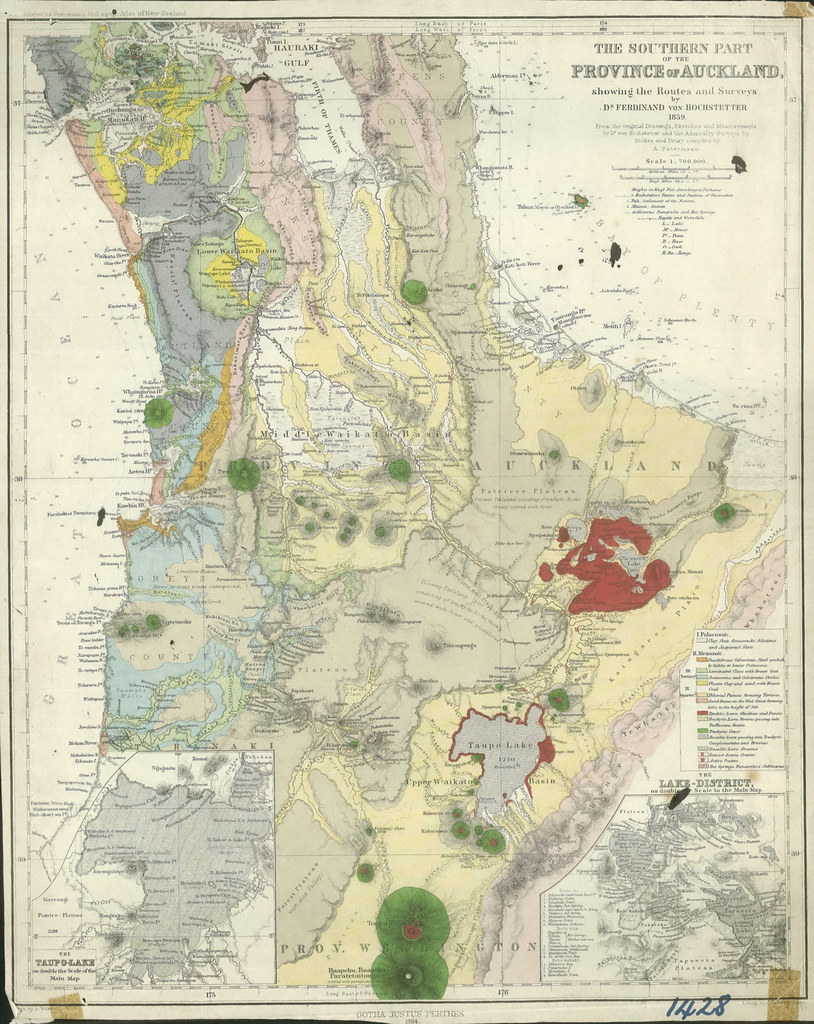

Arriving in India, unencumbered with baggage, on the 13th of August, Sir Colin Campbell, having fully acquainted himself with the condition of affairs, made immediate preparations for crushing the rebellion; and it was when the news arrived that Havelock and Outram, after relieving Lucknow, had themselves been in turn besieged there with the old garrison, that he resolved to put himself at the head of a large force, and go to the rescue. Fortunately, about this time reinforcements reached India; and not a moment having been lost by him in organising his forces, he began his march from Cawnpore on the 9th of November. His army, which included, among others, the 93rd Highlanders who were with him in the Crimea, numbered 5,000 men; and this force was well equipped in every respect, and though there was urgent need to reach Lucknow, all care had been taken that every plan should be carefully prepared, so as to ensure success.

With utmost speed Sir Colin now pushed on; and, as showing the eagerness with which he and his gallant men were longing to reach their goal, within three days they reached the Alum-baugh, where, it will be remembered, the enemy had tried hard to prevent the approach of Havelock and Outram, and where the latter had left the sick and wounded with a guard of 300 men. And it was from the summit of this place, which, though communication between it and the city had been cut off by the rebels, had providentially been left unmolested by them, that Sir Colin was able to signal his arrival to the British Residency.

It was just after the joyful news of the approach of the relieving army had come to the garrison that a heroic feat was undertaken by an Irish civilian, Mr. Thomas Henry Kavanagh, who was one of those who had been shut up in the Residency. At this juncture it was important that, if possible, Sir Colin Campbell should have accurate information as to the condition of the blockaded garrison, and particularly, also, about the route to be taken by him in his advance. But Lucknow was crowded with thousands of rebel troops; and every outlet was closely guarded by them. How, then, could the communication be effected? The brave Kavanagh volunteered to undertake the task. He well knew the perils attending it; knew that if, as was probable, he fell into the rebels’ hands, he would have to endure a death of exquisite torture. He saw, however, that the life or death of the whole garrison depended upon whether Sir Colin could successfully reach the Residency; and so, in the end, though Sir James Outram was reluctant that such terrible danger should be faced, his offer was accepted.

Kavanagh, in his account of the adventure, says: “I was dressed as a budmash, or as an irregular soldier of the city, with sword and shield, native-made shoes, tight trousers, a yellow silk koortah over a tight-fitting white muslin skirt, a yellow-coloured chintz sheet thrown over my shoulders, a cream coloured turban, and a white waistband or cummerbund. My face down to the shoulders and my hands to the wrists were coloured with lampblack, the cork used being dipped in oil to cause the colour to adhere a little.” Thus disguised he started off in the evening, accompanied by a native guide; and having forded the river Goomtee — 4 1/2 feet deep and 100 yards wide — he advanced towards the British camp under cover of the night.

Several adventures now befell him, for he was again and again challenged by the enemy’s pickets, and narrowly escaped detection; while, as he got nearer and nearer to the Alum-baugh, his guide became so terrified that he begged Kavanagh not to proceed farther. He still pressed on, however, meeting with more and more danger, and not till four o’clock did he near the camp. At this hour, he says, “I stopped at the corner of a tope, or grove of trees, to sleep for an hour, which Kunoujee Lal, the guide, entreated I would not do; but I thought he overrated the danger, and, lying down, I told him to see if there was any one in the grove who would tell him where we then were. We had not gone far when I heard the English challenge, ‘Who comes there?’ with a native accent. We had reached a British cavalry outpost; my eyes filled with joyful tears, and I shook the Sikh officer in charge of the picket heartily by the hand. The old soldier was as pleased as myself when he heard from whence I had come, and he was good enough to send two of his men to conduct me to the camp of the advanced guard. An oflicer of her Majesty’s 9th Lancers, who was visiting his pickets, met me on the way, and took me into his tent, where I got dry stockings and trousers, and, which I much needed, a glass of brandy — a liquor I had not tasted for nearly two months.”

We are told that the excitement in the British camp on the arrival of the plucky Irishman was unbounded. Even Sir Colin Campbell, “grim in his sternness and singularly chary of his praise, waxed enthusiastic as Kavanagh sat at his table and told the startling story of that night’s adventure;” and so valuable was the information he was able to impart that the Commander-in-Chief was glad to have Kavanagh by his side to act as guide during the march on Lucknow that soon followed. Eventually, Kavanagh’s services on this, as well as on subsequent occasions, were rewarded with a gift of £2,000, the appointment of Assistant-Commissioner of Oude, and, what such a hero would prize more than all, the Victoria Cross.

On the 14th of November the advance on the city was begun; and from the tower of the Residency, where several of the besieged garrison had betaken themselves, the progress of Sir Colin and his 5,000 men was watched with breathless interest. A different route was chosen from that adopted by Havelock and Outram; and instead of crossing the canal, Sir Colin made first for a strong position held by the enemy at the Dilkhoosha, a hunting castle of the ancient kings of Oude, about three miles from the Residency. A tough fight took place here, but eventually the rebels were driven back and pursued past the Martiniére College, whereupon both that building and the Dilkhoosha fell into the hands of the British. The latter now formed Sir Colin’s head quarters; and early on the 16th, leaving every kind of baggage there, the advance on the Secunder-baugh (or “Alexander’s garden”) was made. This place, the most formidable stronghold of the enemy, was a large square building surrounded by a wall of solid masonry, with loopholes all round; and here it was evident that the rebels, who had mustered in tremendous force, intended to offer desperate resistance. The first move was to dislodge the enemy from a line of barracks which they held outside the Secunder-baugh; and this accomplished, and the barracks turned into a military post, the storming of the main building commenced.

Now began a struggle terrible beyond description; but full of horrors though it was, yet when we remember the unavenged atrocities committed by Nana Sahib and his followers, it was little wonder that at length the British should have given vent to their righteous fury. After battering at the walls of this place for about an hour and a half with little effect, a small breach, only about two feet square, was at last made; and then the order was given to open the assault, for which work the Highlanders and a body of faithful Sikhs were selected.

Dashing forward to the little hole, each man eager to be first, the stormers dragged themselves through as quickly as its narrow limits would permit; and once inside they tore out the iron bars of the windows and leaped headlong in on the astonished defenders. There was no escape for the foe now, for every exit from the place was covered by the British guns, and to the fierce onslaught by the bayonet commenced by the Highlanders and the Sikhs resistance was in vain. “It was,” says one writer, “a horrible struggle. No quarter was asked; except in a few instances, none was given. The grim Highlanders, whenever an appeal was made, hissed in the ear of the suppliant, ‘Cawnpore!’ and the next moment buried the bayonet in his heart…. The hour of vengeance had come…. It was not a sudden rush and the conflict over, but the work of death went on hour after hour for three long hours. Then all was still; and as the crimsoned haggard avengers staggered out of that Aceldama they bore on their persons the testimonials of the terrific work they had accomplished. Few wished to look on the scene the building presented. The floor swam in blood and in the corners and passage-ways lay the dead — 2,000 of them! Thus was Cawnpore avenged — but many a plume that waved proudly in the morning air now dropped mournfully over the cold and pallid face, attesting that the fearful punishment had not been without heavy sacrifice.”

The Secunder-baugh was captured; but the Residency was not yet reached; and Sir Colin’s progress was next barred by a large fortified mosque. Again, however, British valour triumphed after a stubborn fight; and now came the beginning of the end.

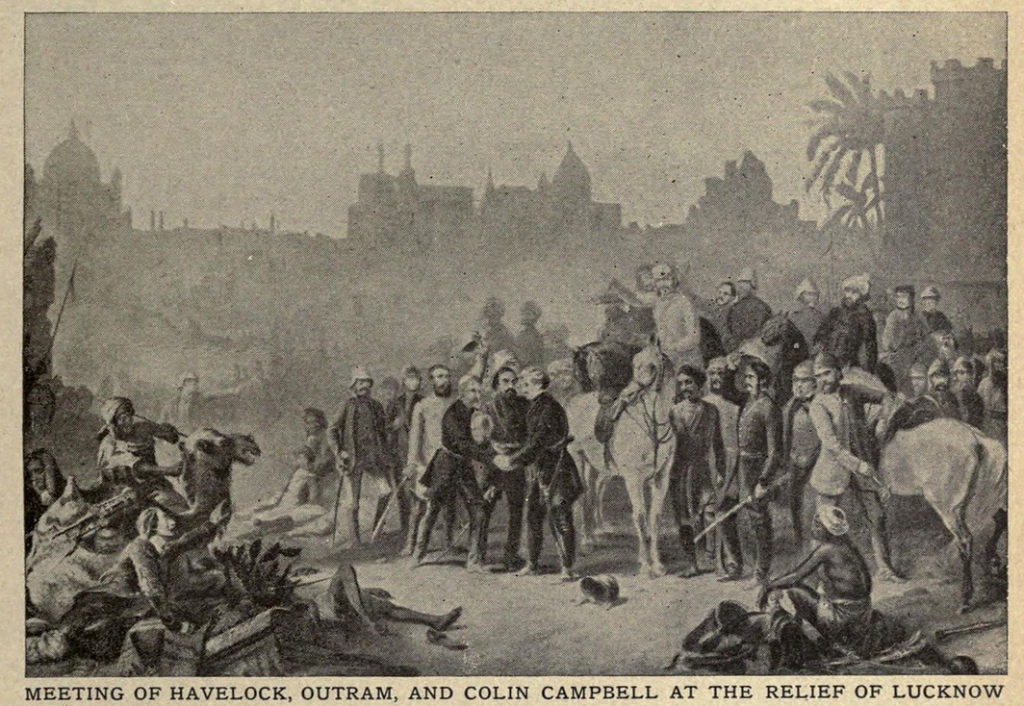

During this time, as Sir Colin advanced nearer and nearer to the Residency, Generals Outram and Havelock had been preparing to co-operate with him as soon as his approach was close enough for them to act with safety; and it is not difficult to imagine with what excitement the pent-up garrison had, from their look-out, watched the relieving force ploughing its way amidst the sea of fire that surrounded it. But nearer and still nearer it had come; and already, on the 16th of November, the garrison had commenced to clear the way from their side. On the next day the junction was effected. Sir Colin had on that morning encountered the rebels at a building known as the Mess House; and it was after this place had been , carried with a rush that the enemy, having made a last despairing stand, were finally, overcome in an enclosure known as the Motee Mahal.

“And then,” says Sir Colin, in his despatch, “I had the inexpressible satisfaction shortly afterwards of greeting Sir James Outram and Sir Henry Havelock, who came out to meet me before the action was at an end. The relief of the besieged garrison had been accomplished.”

What words can describe the joy that now filled the hearts of the heroic men, women, and children, who, after their weeks of suffering and suspense, at length heard the welcome sounds of “The Campbells Are Coming,” piped by the gallant Highlanders, as the Army of Deliverance poured into the Residency? What shouts of triumph and of thankfulness rang through Lucknow on that memorable day! And yet with all this gladness was mingled deepest sorrow; for during this march no fewer than 122 officers and men had been killed and 345 wounded; and who could forget that it was at such cost that success had been achieved? And when only a few days later — by which time Sir Colin had succeeded in removing the garrison, the women and children, and about a thousand sick and wounded, from the Residency — it was known that the beloved Havelock had been stricken down, yet fresh gloom was cast over the British camp.

The main portion of Sir Colin Campbell’s task was now accomplished; but much work was still to be done. First, there was the conveyance to Cawnpore of the rescued garrison — no easy undertaking even under favourable circumstances; but though when he arrived at Cawnpore he found that place in the hands of the enemy, he succeeded in despatching the sick and wounded to Calcutta, after which he attacked the rebels, numbering 25,000, and defeated them at all points.

Following this came Sir Colin’s second campaign in 1858; and during that year not only was Lucknow, which after his departure had, of course, fallen into the hands of the rebels, reconquered by him and Sir James Outram, and British authority firmly re-established in the province of Oude, but by a series of masterly movements — which included the successful operations of Sir Hugh Rose (afterwards Lord Strathnairn) in Central India — the Commander-in-Chief and his able Generals succeeded in reducing one after another of the enemy’s strongholds, and finally in stamping out the rebellion.

Sir Colin in the meantime, in recognition of his achievements, had been raised to the peerage under the title of Baron Clyde of Clydesdale, with a pension of £2,000 a year.

Remaining in India until 1860, Lord Clyde then set sail for his native land. He longed for rest; yet even after arrival in England, though almost worn out, he said — referring to the possibility of being required in Canada — that “if asked to go I am quite ready.” But his services were not needed; and so, his trusty sword returned to its scabbard for ever, he settled down in London; and there — until the 14th of August, 1863 — the great hero spent his remaining days.