Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Napoleon’s Marshals, by R. P. Dunn-Pattison (published 1909).

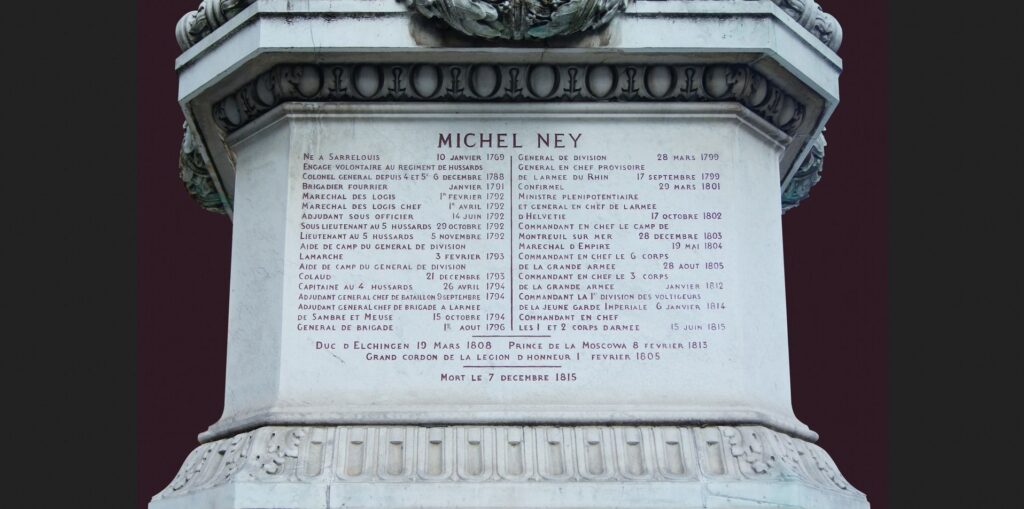

“Go on, Ney; I am satisfied with you; you will make your way.” So spoke a captain of hussars to a young recruit who had attracted his attention. The captain little thought that the zealous stripling would one day become a Marshal of France, the Prince of Moskowa, and famed throughout Europe as the “Bravest of the Brave.” Still, the youth had presentiments of future greatness. Born on January 10, 1769, the son of a poor cooper, of Sarrelouis, more German than French, Michel Ney, at the age of fifteen, was possessed with the idea that he was destined for distinction. His father and mother tried to persuade him to become a miner, but nothing would please the high-spirited boy save the life of a soldier. Accordingly on February 1, 1787, he tramped off to Metz and enlisted as a private in the regiment known as the Colonel General’s Hussars. Physically strong, unusually active, by nature a horseman, he soon attracted the attention of his comrades by his skill in ménage and his command of the sabre, and was chosen to represent his regiment in a duel against the fencing master of another regiment of the garrison. Unfortunately for Ney, the authorities got wind of the affair in time to prevent any decision being arrived at, and the young soldier was punished for breaking regulations by a term of imprisonment; but no sooner was he released than he again challenged his opponent. This time there was no interference, and Ney so severely wounded his adversary that he was unable to continue his profession. Though he thus early in his career distinguished himself by his bravery, tenacity, and disregard of rules, it must not for a moment be thought that he was a mere swashbuckler. With the determination to rise firmly before his eyes, he set about, from the day he enlisted, to learn thoroughly the rudiments of his profession, and to acquire a knowledge of French and the faculty of reading and writing; thus he was able to pass the necessary tests, and quickly gained the rank of sergeant. Ney was fortunate in that he had not to spend long years as a non-commissioned officer with no obvious future before him. The Revolution gave him the opportunity so long desired by Masséna and others, and it was as lieutenant that he started on active service with Dumouriez’s army in 1793. Once on active service it was not long before his great qualities made themselves recognised. Though absolutely uncultivated, save for the smattering of reading and writing which he had picked up in the regimental school, and to outward appearances rather heavy and stupid, in the midst of danger he showed an energy, a quickness of intuition, and a clearness of understanding which hurled aside the most formidable obstacles. Physical fear he never knew; as he said, when asked if he ever felt afraid, “No, I never had time.” In his earliest engagements at Neerwinden and in the north of France, he foreshadowed his future career by the extraordinary bravery and resource he showed in handling his squadron of cavalry during the retreat, on one occasion, with some twenty hussars, completely routing three hundred of the enemy’s horse. This achievement attracted the attention of General Kléber, who sent for Captain Ney and entrusted him with the formation of a body of franc-tireurs of all arms. The franc-tireurs were really recognised brigands. They received no pay or arms and lived entirely on plunder, but were extremely useful for scouting and reconnaissance, and collected a great deal of information under a dashing officer. From this congenial work Ney was summoned in 1796 to command the cavalry of General Coland’s division in the Army of the Sambre and Meuse. There he distinguished himself by capturing Würzburg and two thousand of the enemy with a squadron of one hundred hussars. After this exploit General Kléber refused to listen to his remonstrances and insisted on his accepting his promotion as general of brigade. At the commencement of the campaign of 1797 Ney had the misfortune to be taken prisoner at Giessen. While covering the retreat with his cavalry, he saw a horse artillery gun deserted by its men. Galloping back by himself, he attempted to save the piece, but the enemy’s horse swept down and captured him. His captivity was not long: his exchange was soon effected, and he returned to France in time to join in the agitation against the party of the Clicheans, the only occasion he actively interfered in politics.

On the re-opening of the war in 1799 Ney was sent to command the cavalry of the Army of the Rhine. The campaign was notable for an exploit which admirably illustrates the secret of his success as a soldier. The town of Mannheim, held by a large Austrian garrison, was the key of Southern Germany. The French army was separated from this fortress by the broad Rhine. The enemy was confident that any attempt on the fortress must be preceded by the passage of the river by the whole French army. But Ney, hearing that the enemy’s troops were cantonned in the villages surrounding the town, saw that if a small French force could be smuggled across by night, it might be possible to seize the town by a coup-de-main. The most important thing to ascertain was the exact position of the cantonments of the troops outside the fortress and of the various guards and sentinels inside the town. So important did he consider this information that he determined to cross the river himself and reconnoitre the position in person. Accordingly, general of division as he was, he disguised himself as a Prussian, and trusting to his early knowledge of German, he crossed the river secretly, and carefully noted all the enemy’s preparations, running the risk of being found out and shot as a spy. The following evening, with a weak detachment, he again crossed the river, attacked the enemy’s guards with the bayonet, drove back a sortie of the garrison, and entered the town pell-mell with the flying enemy; and under cover of the darkness, which hid the paucity of his troops, he bluffed the enemy into surrender. The year 1800 brought him further glory under Masséna and Moreau, and he became known throughout the armies of France as the “Indefatigable.”

After the Treaty of Lunéville, the First Consul summoned Ney to Paris, and won his affection by the warmth with which he received him. On his departure Bonaparte presented him with a sword. “Receive this weapon,” he said, “as a souvenir of the friendship and esteem I have towards you. It belonged to a pasha who met his death bravely on the field of Aboukir.” The sword became Ney’s most treasured possession: he was never tired of handling it, and he never let it go out of his sight; but he little thought what ill luck it would bring him later, for it was this famous sword which, in 1815, revealed to the police his hiding-place, and thus indirectly led him to death. The relations between Ney and the First Consul soon became closer. The general married a great friend of Hortense Beauharnais, Mademoiselle Auguie, the daughter of Marie Antoinette’s lady in waiting. Sure of his devotion and perceiving the sternness with which he obeyed orders, in 1802 the First Consul entrusted him with the subjugation of Switzerland. The Swiss army fled before him, and a deputation, charged to make their submission to France, arrived in his camp with the keys of the principal towns. The general met them, listened courteously to their words of submission, then with a wave of the hand refused the keys. With that insight which later led him to warn Napoleon against attempting to trample on the people of Spain and Russia, he replied to the deputation, “It is not the keys I demand: my cannon can force your gates; bring me hearts full of submission, worthy of the friendship of France.” Soon afterwards, with Soult and Davout, Ney was honoured with the command of one of the corps in the army which the First Consul was assembling for the invasion of England. In selecting him for this important post Napoleon showed that power of discrimination which contributed so greatly to his success. For, save in the raid into Switzerland, Ney had not yet been called upon to deal with complicated questions of administration and finance. His reputation rested purely on his extraordinary dash and bravery in the face of the enemy and his power of using to the full the élan which lies latent in all French armies. For when not in touch with the enemy he was notoriously indolent. He never made any attempt to learn the abstract science of war, and until stirred by danger his character seemed to slumber. Others judged him as the Emperor did at St. Helena when he said, “He was the bravest of men; there terminated all his faculties.” But, in spite of this limitation in his character, Napoleon employed him again and again in positions of responsibility, for he knew that Ney’s word once passed was never broken, that his devotion to France and to its ruler was steadfast, that in spite of his peevishness and his fierce outbursts of temper and bitter tirades, when it came to deeds there would be no wavering. Consequently the First Consul availed himself gladly of his great reputation for bravery, considering that hero worship did more to turn the young recruits into soldiers than the greatest organising and administrative talents. Moreover, Napoleon kept an eye on the composition of the staff of his Marshals and generals, and he knew that Ney had in Jomini, the chief of his staff, a man of admirable talent and sagacity, who would turn in their proper direction the sledge-hammer blows of the “Bravest of the Brave.”

With the creation of the Empire Ney was included among the Paladins of the new Charlemagne and received his Marshal’s bâton, the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, and the Order of the Christ of Portugal. But the new Marshal cared little for the life of a courtier, much as he prized his military distinctions. Banquets and feasting offered little attraction to the hero, and he despised riches and rank. “Gentlemen,” said he one day to his aides-de-camp, who were boasting of their families and rich appointments, “Gentlemen, I am more fortunate than you: I got nothing from my family, and I esteemed myself rich at Metz when I had two loaves of bread on the table.” Accordingly, no young subaltern thirsting for glory was happier that Marshal Ney when, in August, 1805, the order came to march on Austria. The campaign, so suddenly commenced, brought the Marshal the hard fighting and the glory he loved so well. In the operations round Ulm, he surpassed himself by the tenacity with which he stuck to the enemy, and, thanks to the skill of Jomini, his errors only added to his fame, and the combat of Elchingen became immortal when Napoleon selected this name as a title for the Marshal when he created him Duke. During the fighting which penned the Austrians into Ulm two sides of the Marshal’s character were clearly seen—his extraordinary bravery and his jealousy. The Emperor, anxious for the complete success of his plans, despatched an officer to command Ney to avoid incurring a repulse and to await reinforcements. The aide-de-camp found him in the faubourg of the town amongst the skirmishers. He delivered his message, whereupon the Marshal replied, “Tell the Emperor that I share the glory with no one; I have already provided for a flank attack.” In September, 1806, Ney was ordered to march to Würzburg to join the Grand Army for the war against Prussia. The campaign gave him just those opportunities which he knew so well how to seize, and before the end of the war the Emperor had changed his sobriquet from the “Indefatigable” to the “Bravest of the Brave.” But glorious as his conduct was, his rash impetuosity more than once seriously compromised Napoleon’s plans. At Jena his rashness and his jealousy of his fellow Marshals caused him to advance before the other corps had taken up their positions. His isolated attack was defeated by the Prussians, and it took the united efforts of Lannes and Soult to rally his shattered battalions and snatch victory from the enemy. But his personal bravery at Jena, his brilliant pursuit of the enemy, the audacity with which he bluffed fourteen thousand Prussians to surrender at Erfurt, and his capture of twenty-three thousand prisoners and eight hundred cannon at the great fortress of Magdeburg made ample amends for his errors.

But glorious as was his success, his impetuosity soon brought him into further disgrace. Detached from the main army on the Lower Vistula in the spring of 1807, he advanced against a mixed force of Prussians and Russians before Napoleon had completed all his plans. The Emperor was furious, and Berthier was ordered to write that, “The Emperor has, in forming his plans, no need of advice or of any one acting on his own responsibility: no one knows his thoughts; it is our duty to obey.” But to obey orders when in contact with the enemy was just what the fiery soldier was unable to do, and the Emperor, recognising this full well, ordered his chief of the staff to write that “His Majesty believes that the position of the enemy is due to the rash manœuvre made by Marshal Ney.” When the main advance commenced the Marshal was summoned to rejoin the Grand Army. He did not arrive in time to take any prominent share in the bloody battle of Eylau; in spite of every exertion, his corps only reached the field of battle as darkness set in. The sight of the awful carnage affected even the warworn Marshal, and made him exclaim, “What a massacre!” and, as he added, “without any issue.” Friedland was a battle after Ney’s own heart. He arrived on the field at the moment Napoleon was opening his grand attack, and with his corps he was ordered to assault the enemy’s left. Hurling division after division, by hand-to-hand fighting he drove the enemy back from their lines, and flung them into the trap of Friedland, there to fall by hundreds under the fierce fire of the French massed batteries. It was his sangfroid which was responsible for the devotion with which the soldiers rushed against the enemy. At the beginning of the action some of the younger grenadiers kept bobbing their heads under the hail of bullets which almost darkened the air. “Comrades,” called out the Marshal, who was on horseback, “the enemy are firing in the air; here am I higher than the top of your busbies, and they don’t hurt me.”

After the peace of Tilsit, Ney, soon Duke of Elchingen, had a year’s repose from war, but in 1808 he was one of those summoned to retrieve the errors arising from Napoleon’s mistaken calculation of the Spanish problem. The selection was an unfortunate one. Accustomed to the ordinary warfare of Central Europe, at his best in the mêlée of battle, in Spain, where organised resistance was seldom met, where the foe vanished at the first contact, the Marshal showed a hesitation and vacillation strangely in contrast with his dashing conduct on the battlefield. Fine soldier as he was, he lacked the essentials of the successful general—imagination and moral courage. He was unable to discern in his mind’s eye what lay on the other side of a hill, and the blank which this lack of imagination caused in his mind affected his nerves, and made him irresolute and irritable. Moreover, in Spain, the success of the Emperor’s plans depended on the loyal co-operation of Marshal with Marshal. But unfortunately Ney, obsessed by jealousy, was most difficult to work with; as Napoleon himself said, “No one knew what it was to deal with two men like Ney and Soult.” From the very outset of his career in Spain he showed a lack of strategic insight and a want of rapidity of movement. Thus it was that he was unable to assist Lannes in the operations which the Emperor had planned for the annihilation of the Spaniards at Tudela. His heart was not in the work, and he made no attempt to hide this from Napoleon. When the Emperor before leaving Spain reviewed his troops, and told him that “Romana would be accounted for in a fortnight; the English are beaten and will make no more effort; that all will be quiet here in three months,” the Duke of Elchingen boldly told him, “The men of this country are obstinate, and the women and children fight; I see no end to the war.” It was with gloomy forebodings, therefore, that he saw the Emperor ride off to France. But what increased his dislike of the whole situation was that his operations were made subservient to those of Soult, his old enemy and rival. The hatred which existed between the two was of long standing, and had burned fiercely ever since the days of Jena, when Soult had been mainly instrumental in retrieving the disaster threatened by Ney’s impetuosity. It came to a head when, after the Duke of Dalmatia’s expulsion from Portugal, the armies of the two Marshals met at Lugo. Soult’s corps arrived without cannon or baggage, a mere armed rabble, and Ney’s men jeered at the disorganised battalions. The Marshals themselves took sides with their men. Matters were not improved when Joseph sent orders that Ney was to consider himself under Soult, and, though Napoleon himself confirmed the decision, it brought no peace between the rival commanders. All through the Talavera campaign there was perpetual discord, and it was Ney’s hesitation, arising from vacillation or jealousy, which prevented Soult from cutting off the English retreat across the Tagus.

After the battle of Wagram, Masséna was despatched to Spain to command the Army of Portugal. The Duke of Elchingen showed to his new chief the same spirit of disobedience and hatred of control. At times slack and supine in his arrangements, as in the preparations for the siege of Ciudad Rodrigo and in his want of energy after the siege of Almeida, at other times upsetting his superiors’ plans by his reckless impetuosity, he was a subordinate whom no one cared to command. Still, when it came to actual contact with the foe, no officer was able to extract so much from his men, and his defeat of Crawford’s division on the Coa and his dash at Busaco were quite up to his great reputation. Before the lines of Torres Vedras his ill-humour broke out again. He bitterly opposed the idea of an assault, and he grumbled at being kept before the position. In fact, nothing that his chief could order was right. It was to a great extent owing to the conduct of the Duke of Elchingen that Masséna was at last compelled to retreat. As he wrote to Berthier, “I have done all I could to keep the army out of Spain as long as possible … but I have been continually opposed, I make bold to say, by the commanders of the corps d’armée, who have roused such a spirit amongst officers and men that it would be dangerous to hold our present position any longer.” When, however, the retreat was at last ordered, Ney showed to the full his immense tactical ability. Although the army was greatly demoralised during the retreat through Portugal, he never lost a single gun or baggage wagon. As Napier wrote, “Day after day Ney—the indomitable Ney—offered battle with the rear guard, and a stream of fire ran along the wasted valleys of Portugal, from the Tagus to the Mondego, from the Mondego to the Coa.” As often as Wellington with his forty thousand men overtook the Marshal with his ten thousand, he was baffled by the tactical cleverness with which his adversary compelled him to deploy his whole force, only to find before him a vanishing rear guard. But while displaying such brilliant ability, the Duke of Elchingen would take no orders from his superior, and when Masséna told him to cover Almeida and Ciudad Rodrigo, he flatly refused and marched off in the opposite direction. Thereon the Prince of Essling was compelled to remove him from his command, and wrote to Berthier, “I have been reduced to an extremity which I have earnestly endeavoured to avoid. The Marshal, the Duke of Elchingen, has arrived at the climax of disobedience. I have given the sixth corps to Count Loison, senior general of division. It is grievous for an old soldier who has commanded armies for so many years to arrive at such a pass … with one of his comrades. The Duke of Elchingen since my arrival has not ceased to thwart me in my military operations…. His character is well known, I will say no more.” Thus Ney returned to France in disgrace with his comrades, and hated by his enemies owing to the licence he allowed his soldiers.

The Emperor, however, much as he insisted on blind obedience to his own orders, soon forgave the Duke of Elchingen, and heaped his wrath on the unfortunate Masséna, whom he held responsible for the failure of the campaign in Portugal. Accordingly, when in 1812 he planned his Russian campaign, he entrusted Ney with the command of the third corps. Under the personal eye of Napoleon, the Duke of Elchingen was a different man to the Ney of Spain. At Smolensk he showed his old brilliancy, and after the battle he opposed the further advance into Russia, maintaining that so far the Russians had never been beaten but only dislodged, that the peasants were hostile, and once again reminding the Emperor of his failure in Spain. It was with great disapprobation that he heard Napoleon accept Caulaincourt’s advice, and determine to advance to Moscow. “Pray heaven,” he said, “that the blarney of the ambassador general may not be more injurious to the army than the most bloody battle.” Gloomy as were his forebodings, they had no effect on his conduct when he met the enemy, and he won for himself the title of Prince of Moskowa in the hard-fought battle outside the walls of Moscow. But it is the retreat that has made his name so glorious. After the first few days he was entrusted with command of the rear guard, and as demoralisation set in he alone was able to keep the soldiers to their duty. At Krasnoi his feeble corps of six thousand men was surrounded by thirty thousand Russians. The main body was beyond recall. When summoned to lay down his arms, he replied, “A Marshal of France never surrenders,” and closing his shattered columns, he charged the enemy’s batteries and drove them from the field. For three days he struggled on surrounded by the foe. On one occasion when the enemy suddenly appeared in force where least expected, his men fell back in dismay, but the Marshal with admirable presence of mind ordered the charge to be beaten, shouting out, “Comrades, now is the moment: forward! they are ours.” At last, with but fifteen hundred men left, he regained the main body near Orcha. When Napoleon heard of their arrival, he rushed to meet the Marshal, exclaiming, “I have three hundred million francs in my coffers at the Tuileries; I would willingly have given them to save Marshal Ney.” He embraced the Duke, saying “he had no regret for the troops which were lost, because they had preserved his dear cousin the Duke of Elchingen.” At the crossing of the Beresina, Ney once again covered himself with glory, and through the remainder of the terrible retreat he commanded the rear guard, and was the last man to cross the Niemen at Kovno and reach German soil. General Dumas, one of the officers of the general staff, relates how he was resting in an inn at Gumbinnen, when one evening a man entered clad in a long brown cloak, wearing a long beard, his face blackened with powder, his whiskers half burned by fire, but his eyes sparkling with brilliant lustre. “Well, here I am at last,” he said. “What, General Dumas, do you not know me?” “No; who are you?” “I am the rear guard of the Grand Army—Marshal Ney. I have fired the last musket on the bridge of Kovno: I have thrown into the Niemen the last of our arms, and I have walked hither, as you see, across the forests.”

The campaign of 1813 saw the Duke of Elchingen once again at the Emperor’s side. At Lützen, his corps of conscripts fought nobly: five times the gallant Ney led them to the attack; five times they responded to the call of their leader. As he himself said, “I doubt if I could have done the same thing with the old grenadiers of the Guard…. The docility and perhaps inexperience of those brave boys served me better than the tried courage of veterans. The French infantry can never be too young.” But at Bautzen he showed another phase of his character. Entrusted with sixty thousand men with orders to make a vast turning movement, his timidity spoiled the Emperor’s careful plans. So hesitating and uncertain were his dispositions that the Allies had ample time to meet his attack and quietly withdrew without being compromised, leaving not a cannon or a prisoner in the hands of the French. Well might the Emperor cry out, “What, after such a butchery no results? no prisoners?” But in spite of Ney’s lack of strategic skill and his well-known vacillation when confronted with problems he did not understand, Napoleon was forced to employ him on an independent command. After Oudinot was beaten at Grosbeeren, he despatched him to take command of the army opposed to the mixed force of the Allies under Bernadotte, which was threatening his communications from the direction of Berlin. But Ney was no more successful than Oudinot. His dispositions were even worse than those of the Duke of Reggio, and at Dennewitz, night alone saved his force from absolute annihilation, while he had to confess to nine hundred killed and wounded and fifteen thousand taken prisoners. He but wrote the truth in his despatch to the Emperor, “I have been totally beaten, and still do not know whether my army has reassembled.” At Leipzig also he was responsible for the want of success during the first day of the battle, and spent the time in useless marching and counter-marching; in this case, however, the faulty orders he received were largely responsible for his errors. But all through the campaign he felt the want of the clear counsel of the born strategist Jomini, his former chief of the staff, who had gone over to the Allies.

During the winter campaign in 1814 in France no one fought more fiercely and stubbornly than the Duke of Elchingen. When the end came and Paris had surrendered, he was one of those who at Fontainebleau refused to march on Paris, in spite of the cries of the Guard “To Paris!” Angered by the tenacity with which the Marshals protested against the folly of such a march, the Emperor at last exclaimed, “The army will obey me.” “No,” replied Ney, “it will obey its commanders.” Macdonald, who had just arrived with his weary troops, backed him up, exclaiming, “We have had enough of war without kindling a civil war.” Thereon Napoleon was induced to sign a proclamation offering to abdicate; and Caulaincourt, Macdonald, and Ney set out for Paris to try and get terms from the Czar. Once in the capital the Marshal seemed to despair of his commission. Feeble and irresolute, he was easily gained over by Talleyrand, and at once made his formal adhesion to the provisional government. When the commissioners returned to the Emperor, he saw but too clearly that his day was done. “Oh,” he exclaimed, “you want repose; have it then; alas! you know not how many disappointments and dangers await you on your beds of down.”

The Emperor’s prophecy was but too true. Though honours were showered upon him, the peace which followed the restoration of the Bourbons brought but little satisfaction and enjoyment to the Duke of Elchingen. Accustomed to the bustle and hurry of a soldier’s life, he was too old to acquire the tastes of a life of tranquillity. Books brought him no satisfaction, since he could scarcely read; society frightened him, and his plain manners and blunt speech shocked the salons of Paris and grated on the nerves of the courtiers. By nature ascetic, he hated dissipation. Moreover, his family life was by no means happy. His wife, ambitious, fond of luxury and pleasure, was unable to share his pursuits and tastes, and worried her husband with childish complaints of loss of prestige at the new court. Consequently the blunt old soldier was only too glad to leave her at his hotel in Paris, and bury himself in his estate in the country, where field sports offered him a recreation he could appreciate, and his old comrades and country neighbours afforded him a society at least congenial.

From this peaceful life at Coudreaux the Marshal was suddenly summoned on March 6, 1815, to Paris. On arriving there he was met by his lawyer, who informed him of Napoleon’s descent on Fréjus. “It is a great misfortune,” he said; “what is the Government doing? Who are they going to send against that man?” Then he hurried off to the Minister of War to receive his instructions. He was ordered to Besançon to take command of the troops there, and to help oppose Napoleon’s advance on Paris. Before starting for his headquarters he went to pay his respects to the King, and expressed his indignation at the Emperor’s action, promising “to bring him back in an iron cage.” On arriving at his command he found everything in confusion, and the soldiers ready at any moment to declare for the Emperor. Ney had but one thought, and that to save the King. In reply to a friend who told him that the soldiers could not fight the Emperor, he replied, “They shall fight; I will begin the action myself, and run my sword to the hilt in the breast of the first who hesitates to follow my example.” But when he arrived, on the evening of the 13th, at Lons la Saulnier he was met by the news that on all sides the troops were deserting, and that the Duke of Orleans and Monsieur had been compelled to withdraw from Lyons. That same evening emissaries arrived from Napoleon alleging that all the Marshals had promised to go over, and that the Congress of Vienna had approved of the overthrow of the Bourbons, assuring the Marshal that the Emperor would receive him as on the day after the battle of Moskowa. While but half convinced by these specious arguments and a prey to doubt, news arrived that his vanguard at Bourg had deserted, and that the inhabitants of Châlons-sur-Saône had seized his artillery. In his agony he exclaimed to the emissaries, “It is impossible for me to stop the water of the ocean with my own hand.” On the morrow he called the generals of division to give him counsel; one of them was Bourmont, a double-dyed traitor who deserted Napoleon on the eve of Waterloo; the other was the stern old republican warrior Lecourbe. They could give him but little advice, so at last the fatal decision was made, and Ney called his troops together and read the proclamation drawn up by Napoleon.

Scarcely had he done so than he began to perceive the enormity of his action. Meanwhile he wrote an impassioned letter to Napoleon urging him to seek no more wars of conquest. It might suit the Emperor’s policy to cause the Marshal to desert those to whom he had sworn allegiance, but he mistrusted men who broke their word, and though he received Ney with outward cordiality, he saw but little of the “black beast,” as he called him, during the Hundred Days, for the Duke of Elchingen, full of remorse and shame, hid himself at Coudreaux. It was not till the end of May that Napoleon summoned him to Paris, and greeted him with the words, “I thought you had become an émigré.” “I ought to have done it long ago,” replied the Marshal; “now it is too late.” Still the Emperor kept him without employment till on June 11th he sent him to inspect the troops around Lille, and from there summoned him to join the army before Charleroi on the afternoon of June 15th. Immediately on his arrival he was put in command of the left wing of the army, composed of Reille and d’Erlon’s corps, and received verbal orders to push northwards and occupy Quatre Bras. The Marshal’s task was not an enviable one. He had to improvise a staff and make himself acquainted with his subordinates and at the same time try and elucidate the contradictory orders of his old enemy Soult, now chief of the staff to the Emperor. Accordingly, when on the evening of the 15th his advance guard found Quatre Bras held by the enemy, he decided to make no attack that night. But on the morning of the 16th he made a still greater error. For not only did he neglect to make a reconnaissance, which would have showed him that he was opposed by a mere handful of troops, but, slothful as ever, he omitted to give orders for the proper concentration of his divisions, which were strung out along sixteen miles of road. A day begun thus badly was bound to bring difficulties. But these difficulties were enormously increased in the afternoon. After three despatches ordering him to carry Quatre Bras with all his force, he received a fourth written by Soult at Napoleon’s order telling him to move to the right to support Grouchy in his attack on the Prussians, ending with the words, “The fate of France is in your hands, therefore do not hesitate to move according to the Emperor’s commands.” To add further to his difficulties, d’Erlon’s corps was detached from his command without his knowledge. In this distracted condition, the Marshal lost all control over himself, calling out, “Ah, those English balls! I wish they were all in my belly!” Thus it was, mad with rage, that he rode up to Kellermann, calling out, “We must make a supreme effort. Take your cavalry and fling yourself upon the English centre. Crush them—ride them down!” But it was too late. Wellington himself with thirty thousand men now held Quatre Bras. The Marshal had himself to thank for his want of success, for if he had been less slothful in the morning, the battle would have been won before the contradictory orders could have had any effect on his plans. On the morning of the 17th the dispirited Prince of Moskowa took no steps to find out what his enemy was doing, although he received orders from the Emperor at ten o’clock to occupy Quatre Bras if there was only a rear guard there. Accordingly the English had ample time to retreat. When Napoleon hurried up in pursuit at 2 p.m. he greeted his lieutenant with the bitter reproach, “You have ruined France!” But though the Emperor recognised that he was no longer the Ney of former days, he still retained him in his command. At Waterloo the Marshal showed his old dash on the battlefield. The left wing was hurled against the Allies with a vehemence that recalled the Prince of Moskowa’s conduct in the Russian campaign. But, impetuous as ever, finding he could not crush the stubborn foe with his infantry, he rushed back and prematurely ordered up 5,000 of the cavalry of the Guard. “He has compromised us again,” growled his old enemy Soult, “as he did at Jena.” “It is too early by an hour,” exclaimed the Emperor, “but we must support him now that he has done it.” The mistake was fatal to Napoleon’s plans. In vain the French cavalry charged the English squares, still unshaken by artillery and infantry fire. Meanwhile the Prussians appeared on the allied left. The Emperor staked his last card, and ordered the Guard to make one last effort to crush the English infantry. Sword in hand the gallant Prince of Moskowa led the magnificent veterans to the attack. But the fire of the English lines swept them down by hundreds. A shout arose, “La garde recule.” Ney, the indomitable, in vain seeking death, was swept away by the mass, his clothing in rags, foaming at the mouth, his broken sword in his hand, rushing from corps to corps, trying to rally the runaways with taunts of “Cowards, have you forgotten how to die?” At one moment he passed d’Erlon as they were swept along in the rush, and screamed out to him, “If you and I come out of this alive, d’Erlon, we shall be hanged.” Well it had been for him if he could have found the death he so eagerly sought. Five horses were shot under him, his clothes were riddled with bullets, but he was reserved for a sinister fate.

The Marshal returned to Paris and witnessed the capitulation and second abdication. Thereafter he had thoughts of withdrawing to Switzerland or to America. But unfortunately he considered himself safe under the terms of the capitulation, and, anxious to clear his name for the sake of his children, he remained hidden at the château of Bessonis, near Aurillac, waiting to see what the attitude of the Government would be. There he was discovered by a zealous police official, who caught sight of the Egyptian sabre Napoleon had presented to him in 1801. He was at once arrested and taken to Paris. The military court appointed to try him declared itself unable to try a peer of France. Accordingly the House of Peers was ordered to proceed with his trial, and found him guilty by a majority of one hundred and sixty-nine to nineteen. The Marshal’s lawyers tried to get him off by the subterfuge that he was no longer a Frenchman, since his native town, Sarrelouis, had been taken from France. But Ney would hear of no such excuse. “I am a Frenchman,” he cried, “and will die a Frenchman.” Early on the following day, December 7, 1815, the sentence was read to the prisoner. The officer entrusted with this melancholy duty commenced to read his titles, Prince of Moskowa, Duke of Elchingen, &c. But the Marshal cut him short: “Why cannot you simply say ‘Michel Ney, once a French soldier and soon to be a heap of dust’?” At eight o’clock in the morning the Marshal, with a firm step, was conveyed to the place of execution. To the officer who prepared to bandage his eyes he said, “Are you ignorant that for twenty-five years I have been accustomed to face both ball and bullet?” Then, taking off his hat, he said, “I declare before God and man that I have never betrayed my country. May my death render her happy. Vive la France!” Then, turning to the soldiers, he gave the word, “Soldiers, fire!”

Thus, in his forty-seventh year, the Prince of Moskowa, a peasant’s son, but now immortal as the “Bravest of the Brave,” expiated his error. Pity it was that he had not the courage of his gallant subordinate at Lons la Saulnier, who had broken his sword in pieces with the words, “It is easier for a man of honour to break iron than to infringe his word.” Looking backward, and calmly reading the evidence of the trial, it is clear that Ney set out in March, 1815, with every intention to remain faithful to the King. But his moral courage failed him; and the glamour of his old life, and the contact with the iron will of the great Corsican, broke down his principles. To some the punishment meted out to him seemed hard; but when the Emperor heard of his execution he said that he only got his deserts. “No one should break his word. I despise traitors. Ney has dishonoured himself.” And the Duke of Wellington refused to plead for the Marshal, for he said “it was absolutely necessary to make an example.” But the clearest proof of the justice of the penalty was the fact that from the fatal day at Lons la Saulnier the Marshal was never himself again, and he who, during those terrible days in Russia, had been able to sleep like a little child, never could sleep in peace.

Among the Marshals of Napoleon, Ney, with his title of the “Bravest of the Brave,” and his magnificent record of hard fighting, will always appeal to those who love romance. But, great fighter as he was, he was not a great general. At times, at St. Helena, Napoleon, remembering his mistakes at Quatre Bras and Waterloo, used to say that he ought not to have made him a Marshal, for he only had the courage and honesty of a hussar, forgetting his words in Russia, “I have three hundred millions francs in my coffers at the Tuileries; I would willingly have given them to save Marshal Ney.” But, cruel as it may seem, perhaps the Emperor expressed his real opinion of him when he said, “He was precious on the battlefield, but too immoral and too stupid to succeed.” In action he was always master of himself, but as Jomini, his old chief of the staff, wrote of him, “Ney’s best qualities, his heroic valour, his rapid coup d’œil, and his energy, diminished in the same proportion that the extent of his command increased his responsibility. Admirable on the battlefield, he displayed less assurance not only in council, but whenever he was not actually face to face with the enemy.” In a word, he lacked that marked intellectual capacity which is the chief characteristic of great soldiers like Hannibal, Cæsar, Napoleon, and Wellington.