Editor’s note: The following is extracted from A Book of Discovery, by M.B. Synge (published 1912)

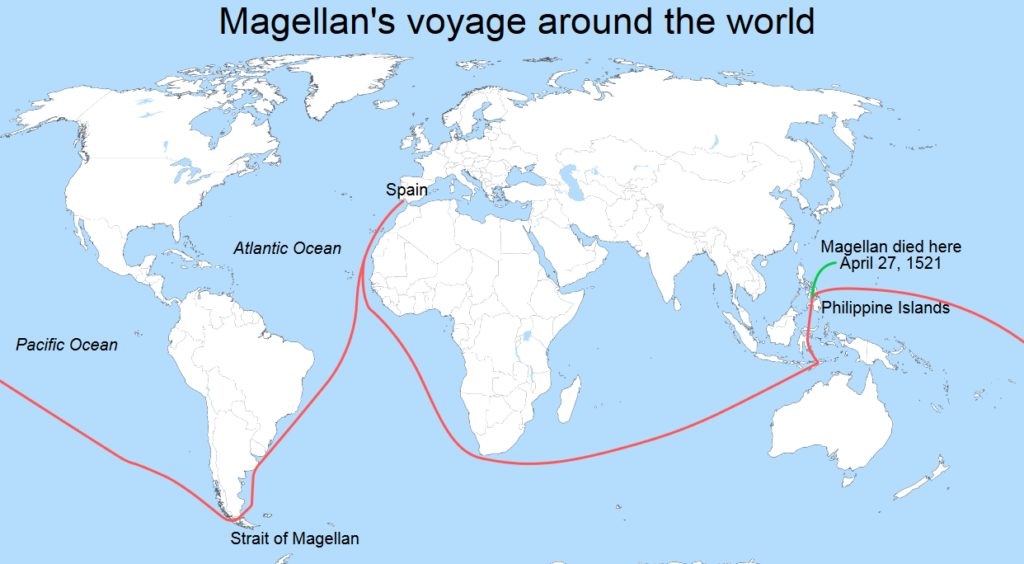

It is said that Ferdinand Magellan, the hero of all geographical discovery, with his circumnavigation of the whole round world, had cruised about the Spice Islands, but what he really knew of them from personal experience no one knows. He had served under Almeida, and with Albuquerque had helped in the conquest of Malacca. After seven years of a “vivid life of adventure by sea and land, a life of siege and shipwreck, of war and wandering,” inaction became impossible. He busied himself with charts and the art of navigation. He dreamt of reaching the Spice Islands by sailing west, and after a time he laid his schemes before the King of Portugal. Whether he was laughed at as a dreamer or a fool we know not. His plans were received with cold refusal. History repeats itself. Like Christopher Columbus twenty years before, Magellan now said good-bye to Portugal and made his way to Spain.

Since the first discovery of the New World by Spain, that country had been busy sending out explorer after explorer to discover and annex new portions of America. Bold navigators, Pinzon, Mendoza, Bastidas, Juan de la Cosa, and Solis—these and others had almost completed the discovery of the east coast, indeed, Solis might have been the first to see the great Pacific Ocean had he not been killed and eaten at the mouth of the river La Plata. This great discovery was left to Vasco Nunez de Balboa, who first saw beyond the strange New World from the Peak of Darien. Now his discovery threw a lurid light on to the limitation of land that made up the new country and illuminated the scheme of Magellan.

Balboa was “a gentleman of good family, great parts, liberal education, of a fine person, and in the flower of his age.” He had emigrated to the new Spanish colony of Haiti, where he had got into debt. No debtor was allowed to leave the island, but Balboa, the gentleman of good family, yearned for further exploration; he “yearned beyond the sky-line where the strange roads go down.” And one day the yearning grew so great that he concealed himself in a bread cask on board a ship leaving the shores of Haiti. For some days he remained hidden. When the ship was well out to sea he made his appearance. Angry, indeed, was the captain—so angry that he threatened to land the stowaway on a desert island. He was, however, touched by the entreaties of the crew, and Balboa was allowed to sail on in the ship. It was a fortunate decision, for when, soon after, the ship ran heavily upon a rock, it was the Spanish stowaway Balboa who saved the party from destruction. He led the shipwrecked crew to a river of which he knew, named Darien by the Indians. He did not know that they stood on the narrow neck of land—the isthmus of Panama—which connects North and South America. The account of the Spanish intrusion is typical: “After having performed their devotions, the Spaniards fell resolutely on the Indians, whom they soon routed, and then went to the town, which they found full of provisions to their wish. Next day they marched up the country among the neighbouring mountains, where they found houses replenished with a great deal of cotton, both spun and unspun, plates of gold in all to the value of ten thousand pieces of fine gold.”

A trade in gold was set up by Balboa, who became governor of the new colony formed by the Spaniards; but the greed of these foreigners quite disgusted the native prince of these parts.

“What is this, Christians? Is it for such a little thing that you quarrel? If you have such a love of gold, I will show you a country where you may fulfill your desires. You will have to fight your way with great kings whose country is distant from our country six suns.”

So saying, he pointed away to the south, where he said lay a great sea. Balboa resolved to find this great sea. It might be the ocean sought by Columbus in vain, beyond which was the land of great riches where people drank out of golden cups. So he collected some two hundred men and started forth on an expedition full of doubt and danger. He had to lead his troops, worn with fatigue and disease, through deep marshes rendered impassable with heavy rains, over mountains covered with trackless forest, and through defiles from which the Indians showered down poisoned arrows.

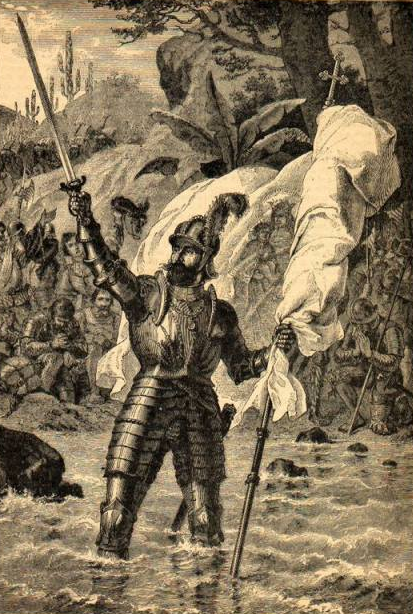

At last, led by native guides, Balboa and his men struggled up the side of a high mountain. When near the top he bade his men stop. He alone must be the first to see the great sight that no European had yet beheld. With “transports of delight” he gained the top and, “silent upon a peak in Darien,” he looked down on the boundless ocean, bathed in tropical sunshine. Falling on his knees, he thanked God for his discovery of the Southern Sea. Then he called up his men. “You see here, gentlemen and children mine, the end of our labors.”

The notes of the “Te Deum” then rang out on the still summer air, and, having made a cross of stones, the little party hurried to the shore. Finding two canoes, they sprang in, crying aloud joyously that they were the first Europeans to sail on the new sea, whilst Balboa himself plunged in, sword in hand, and claimed possession of the Southern Ocean for the King of Spain. The natives told him that the land to the south was without end, and that it was possessed by powerful nations who had abundance of gold. And Balboa thought this referred to the Indies, knowing nothing as yet of the riches of Peru.

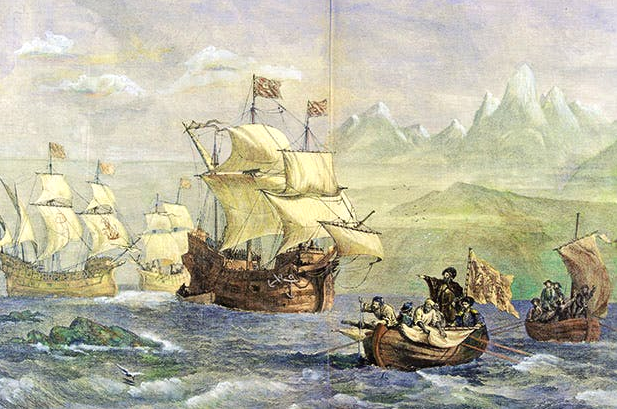

It is melancholy to learn that the man who made this really great discovery was publicly hanged four years later in Darien. But his news had reached Magellan. There was then a great Southern Ocean beyond the New World. He was more certain than ever now that by this sea he could reach the Spice Islands. Moreover, he persuaded the young King of Spain that his country had a right to these valuable islands, and promised that he would conduct a fleet round the south of the great new continent westward to these islands. His proposal was accepted by Charles V, and the youthful Spanish monarch provided Spanish ships for the great enterprise. The voyage was not popular, the pay was low, the way unknown, and in the streets of Seville the public crier called for volunteers. Hence it was a motley crew of some two hundred and eighty men, composed of Spaniards, Portuguese, Genoese, French, Germans, Greeks, Malays, and one Englishman only. There were five ships. “They are very old and patched,” says a letter addressed to the King of Portugal, “and I would be sorry to sail even for the Canaries in them, for their ribs are soft as butter.”

Magellan hoisted his flag on board the Trinidad of one hundred and ten tons’ burden. The largest ship, S. Antonio, was captained by a Spaniard—Cartagena; the Conception, ninety tons, by Gaspar Quesada; the Victoria of eighty-five tons, who alone bore home the news of the circumnavigation of the world, was at first commanded by the traitor Mendoza; and the little Santiago, seventy-five tons, under the brother of Magellan’s old friend Serrano.

What if the commander himself left a young wife and a son of six months old? The fever of discovery was upon him, and, flying the Spanish flag for the first time in his life, Magellan, on board the Trinidad, led his little fleet away from the shores of Spain. He never saw wife or child again. Before three years had passed all three were dead.

Carrying a torch or faggot of burning wood on the poop, so that the ships should never lose sight of it, the Trinidad sailed onwards.

“Follow the flagship and ask no questions.”

Such were his instructions to his not too loyal captains.

They had left Seville on 20th September 1519. A week later they were at the Canaries. Then past Cape Verde, and land faded from their sight as they made for the south-west. For some time they had a good run in fine weather. Then “the upper air burst into life” and a month of heavy gales followed. The Italian count, who accompanied the fleet, writes long accounts of the sufferings of the crew during these terrific Atlantic storms.

“During these storms,” he says, “the body of St. Anselm appeared to us several times; one night that it was very dark on account of the bad weather the saint appeared in the form of a fire lighted at the summit of the mainmast and remained there near two hours and a half, which comforted us greatly, for we were in tears only expecting the hour of perishing; and, when that holy light was going away from us, it gave out so great a brilliancy in the eyes of each, that we were like people blinded and calling out for mercy. For without any doubt nobody hoped to escape from that storm.”

Two months of incessant rain and diminished rations added to their miseries. The spirit of mutiny now began to show itself. Already the Spanish captains had murmured against the Portuguese commander.

“Be they false men or true, I will fear them not; I will do my appointed work,” said the commander firmly.

It was not till November that they made the coast of Brazil in South America, already sighted by Cabral and explored by Pinzon. But the disloyal captains were not satisfied, and one day the captain of the S. Antonio boarded the flagship and openly insulted Magellan. He must have been a little astonished when the Portuguese commander seized him by the collar, exclaiming: “You are my prisoner!” giving him into custody and appointing another in his place.

Food was now procurable, and a quantity of sweet pine-apples must have had a soothing effect on the discontented crews. The natives traded on easy terms. For a knife they produced four or five fowls; for a comb, fish for ten men; for a little bell, a basket full of sweet potatoes. A long drought had preceded Magellan’s visit to these parts, but rain now began with the advent of the strangers, and the natives made sure that they had brought it with them. Such an impression once made there was little difficulty in converting them to the Christian faith. The natives joined in prayer with the Spaniards, “remaining on their knees with their hands joined in great reverence so that it was a pleasure to see them,” writes one of the party.

The day after Christmas again found them sailing south by the coast, and early in the New Year they anchored at the mouth of the Rio de la Plata, where Solis had lost his life at the hands of the cannibals some five years before. He had succeeded Vespucci in the service of Spain, and was exploring the coast when a body of Indians, “with a terrible cry and most horrible aspect,” suddenly rushed out upon them, killed, roasted, and devoured them.

Through February and March, Magellan led his ships along the shores of bleak Patagonia seeking for an outlet for the Spice Islands. Winter was coming on and no straits had yet been found. Storm after storm now burst over the little ships, often accompanied by thunder and lightning; poops and forecastles were carried away, and all expected destruction, when “the holy body of St. Anselm appeared and immediately the storm ceased.”

It was quite impossible to proceed farther to the unknown south, so, finding a safe and roomy harbor, Magellan decided to winter there. Port St. Julian he named it, and he knew full well that there they must remain some four or five months. He put the crew on diminished rations for fear the food should run short before they achieved their goal. This was the last straw. Mutiny had long been smouldering. The hardships of the voyage, the terrific Atlantic storms, the prospect of a long Antarctic winter of inaction on that wild Patagonian coast—these alone caused officers and men to grumble and to demand an immediate return to Spain.

But the “stout heart of Magellan” was undaunted.

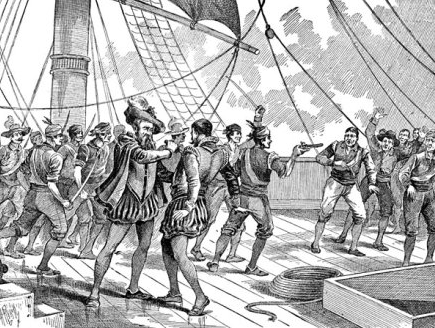

On Easter Day the mutiny began. Two of the Spanish captains boarded the S. Antonio, seized the Portuguese captain thereof, and put him in chains. Then stores were broken open, bread and wine generously handed round, and a plot hatched to capture the flagship, kill Magellan, seize his faithful Serrano, and sail home to Spain.

The news reached Magellan’s ears. He at once sent a messenger with five men bearing hidden arms to summon the traitor captain on board the flagship. Of course he stoutly refused. As he did so, the messenger sprang upon him and stabbed him dead. As the rebellious captain fell dead on the deck of his ship, the dazed crew at once surrendered. Thus Magellan by his prompt measures quelled a mutiny that might have lost him the whole expedition. No man ever tried to mutiny again while he lived and commanded.

The fleet had been two whole months in the Port S. Julian without seeing a single native.

“However, one day, without anyone expecting it, we saw a giant, who was on the shore of the sea, dancing and leaping and singing. He was so tall that the tallest of us only came up to his waist; he was well built; he had a large face, painted red all round, and his eyes also were painted yellow around them, and he had two hearts painted on his cheeks; he had but little hair on his head and it was painted white.”

The great Patagonian giant pointed to the sky to know whether these Spaniards had descended from above. He was soon joined by others evidently greatly surprised to see such large ships and such little men. Indeed, the heads of the Spaniards hardly reached the giants’ waists, and they must have been greatly astonished when two of them ate a large basketful of biscuits and rats without skinning them and drank half a bucket of water at each sitting.

With the return of spring weather in October 1520, Magellan led the little fleet upon its way. He was rewarded a few days later by finding the straits for which he and others had been so long searching.

“It was the straight,” says the historian simply, “now cauled the straight of Magellans.”

A struggle was before them. For more than five weeks the Spanish mariners fought their way through the winding channels of the unknown straits. On one side rose high mountains covered with snow. The weather was bad, the way unknown. Do we wonder to read that “one of the ships stole away privily and returned into Spain,” and the remaining men begged piteously to be taken home? Magellan spoke “in measured and quiet tones”: “If I have to eat the leather of the ships’ yards, yet will I go on and do my work.” His words came truer than he knew. On the southern side of the strait constant fires were seen, which led Magellan to give the land the name it bears to-day—Tierra del Fuego. It was not visited again for a hundred years.

At last the ships fought their way to the open sea—Balboa’s Southern Ocean—and “when the Captain Magellan was past the strait and saw the way open to the other main sea he was so glad thereof that for joy the tears fell from his eyes.”

The expanse of calm waters seemed so pleasant after the heavy tiring storms that he called the still waters before him the Pacific Ocean. Before following him across the unknown waters, let us recall the quaint lines of Camoens:

Three little ships had now emerged, battered and worn, manned by crews gaunt and thin and shivering. Magellan took a northerly course to avoid the intense cold, before turning to cross the strange obscure ocean, which no European had yet realized. Just before Christmas the course was altered and the ships were turned to the north-west, in which direction they expected soon to find the Spice Islands. No one had any idea of the vastness of the Pacific Ocean.

“Well was it named the Pacific,” remarks the historian, “for during three months and twenty days we met with no storm.”

Two months passed away, and still they sailed peacefully on, day after day, week after week, across a waste of desolate waters.

At last one January day they sighted a small wooded island, but it was uninhabited; they named it S. Paul’s Island and passed on their way. They had expected to find the shores of Asia close by those of America. The size of the world was astounding. Another island was passed. Again no people, no consolation, only many sharks. There was bitter disappointment on board. They had little food left. “We ate biscuit, but in truth it was biscuit no longer, but a powder full of worms. So great was the want of food that we were forced to eat the hides with which the main yard was covered to prevent the chafing against the rigging. These hides we exposed to the sun first to soften them by putting them overboard for four or five days, after which we put them on the embers and ate them thus. We had also to make use of sawdust for food, and rats became a great delicacy.” No wonder scurvy broke out in its worst form—nineteen died and thirteen lay too ill to work.

For ninety-eight days they sailed across the unknown sea, “a sea so vast that the human mind can scarcely grasp it,” till at last they came on a little group of islands peopled with savages of the lowest type—such expert thieves that Magellan called the new islands the Ladrones or isle of robbers. Still, there was fresh food here, and the crews were greatly refreshed before they sailed away. The food came just too late to save the one Englishman of the party—Master Andrew of Bristol—who died just as they moved away. Then they found the group afterwards known as the Philippines (after Philip II. of Spain). Here were merchants from China, who assured Magellan that the famous Spice Islands were not far off. Now Magellan had practically accomplished that he set out to do, but he was not destined to reap the fruits of his victory.

With a good supply of fresh food the sailors grew better, and Magellan preferred cruising about the islands, making friends of the natives and converting them to Christianity, to pushing on for the Spice Islands. Here was gold, too, and he busied himself making the native rulers pay tribute to Spain. Easter was drawing near, and the Easter services were performed on one of the islands. A cross and a crown of thorns was set upon the top of the highest mountain that all might see it and worship. Thus April passed away and Magellan was still busy with Christians and gold. But his enthusiasm carried him too far. A quarrel arose with one of the native kings. Magellan landed with armed men, only to be met by thousands of defiant natives. A desperate fight ensued. Again and again the explorer was wounded, till “at last the Indians threw themselves upon him with iron-pointed bamboo spears and every weapon they had and ran him through—our mirror, our light, our comforter, our true guide—until they killed him.”

Such was the tragic fate of Ferdinand Magellan, “the greatest of ancient and modern navigators,” tragic because, after dauntless resolution and unwearied courage, he died in a miserable skirmish at the last on the very eve of victory.

With grief and despair in their hearts, the remaining members of the crew, now only one hundred and fifteen, crowded on to the Trinidad and Victoria for the homeward voyage. It was September 1522 when they reached the Spice Islands—the goal of all their hopes. Here they took on board some precious cloves and birds of Paradise, spent some pleasant months, and, laden with spices, resumed their journey. But the Trinidad was too overladen with cloves and too rotten to undertake so long a voyage till she had undergone repair, so the little Victoria alone sailed for Spain with sixty men aboard to carry home their great and wonderful news. Who shall describe the terrors of that homeward voyage, the suffering, starvation, and misery of the weary crew? Man after man drooped and died, till by the time they reached the Cape Verde Islands there were but eighteen left.

When the welcome shores of Spain at length appeared, eighteen gaunt, famine-stricken survivors, with their captain, staggered ashore to tell their proud story of the first circumnavigation of the world by their lost commander, Ferdinand Magellan.

We miss the triumphal return of the conqueror, the audience with the King of Spain, the heaped honors, the crowded streets, the titles, and the riches. The proudest crest ever granted by a sovereign—the world, with the words: “Thou hast encompassed me”—fell to the lot of Del Cano, the captain who brought home the little Victoria. For Magellan’s son was dead, and his wife Beatrix, “grievously sorrowing,” had passed away on hearing the news of her husband’s tragic end.