A while back, we reviewed the great film, Sergeant York. It is a classic, and we do encourage everyone to watch it. However, the man upon whom the film is based, Alvin. C. York, is an interesting case study in the type of man who is needed to bring sanity back to our culture. While his exploits occurred a century ago, we have much to learn from him. In fact, keeping in line with our recent posts on generations, York was his era’s Gen Xer. Yes, you read that right. As Strauss and Howe argue, generations operate in a cycle, alternating between four distinct generational archetypes. Gen X is a Nomad generation, in their terminology, as was York’s “Lost” Generation – those men who fought in WWI, and entered middle age during WW II.

If their argument is correct, then many of the same characteristics that describe Gen X will also apply to the Lost Generation, and they do.

Alvin York was one of 11 children, born a log cabin in Tennessee. He was afforded little opportunity for education, as his father required his children to work to help feed the family. They harvested their own food, made their own clothes, and York’s father worked as a blacksmith to supplement their meager income. When York was in his early 20s, his father died, so York stayed home (two older brothers had already married and left) to help raise his younger siblings. During this time, he took on jobs in railroad construction and logging to help out.

He was a hell-raiser, well known for his heavy drinking and propensity for fighting. He was arrested several times. Even during this time in his life, he was a regular church-goer, though his lifestyle did not really demonstrate it. While the movie version shows him being struck by lightning and then rededicating himself to God, that was a fictional event. What really happened was that a close friend was killed in a bar fight, causing York to reassess his life. At the end of 1914, a revival at his local church led to his true conversion experience. Once this happened, he totally changed his ways, becoming a devout Christian. His small denomination was pacifist, and so when he was forced to register for the draft, upon the United States entering WWI, he checked the box to be recognized as a Conscientious Objector because “I don’t want to fight.” As his denomination was not recognized, his request was denied, so he was drafted and put into a combat unit. His commanding officers, also Christians, spent time with him, discussing his beliefs and offering counter arguments that would allow a Christian to engage in warfare. After reflection, York decided to follow through and do his duty as a soldier.

His exploits in the war demonstrate his heroism. His small detachment was pinned down by German machine gun fire. His superiors were all killed or wounded. So York took action, singlehandedly killing or capturing his enemies. He began to pick off the Germans one by one:

I teched off the sixth man first; then the fifth; then the fourth; then the third; and so on. That’s the way we shoot wild turkeys at home. You see we don’t want the front ones to know that we’re getting the back ones, and then they keep on coming until we get them all.

Between each shot, York called for the Germans to surrender if they wanted the firing to stop. Eventually they did, and York captured the remaining 90 or so enemy. He had killed between 20-28 Germans. For this action, he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, in addition to many other medals and awards.

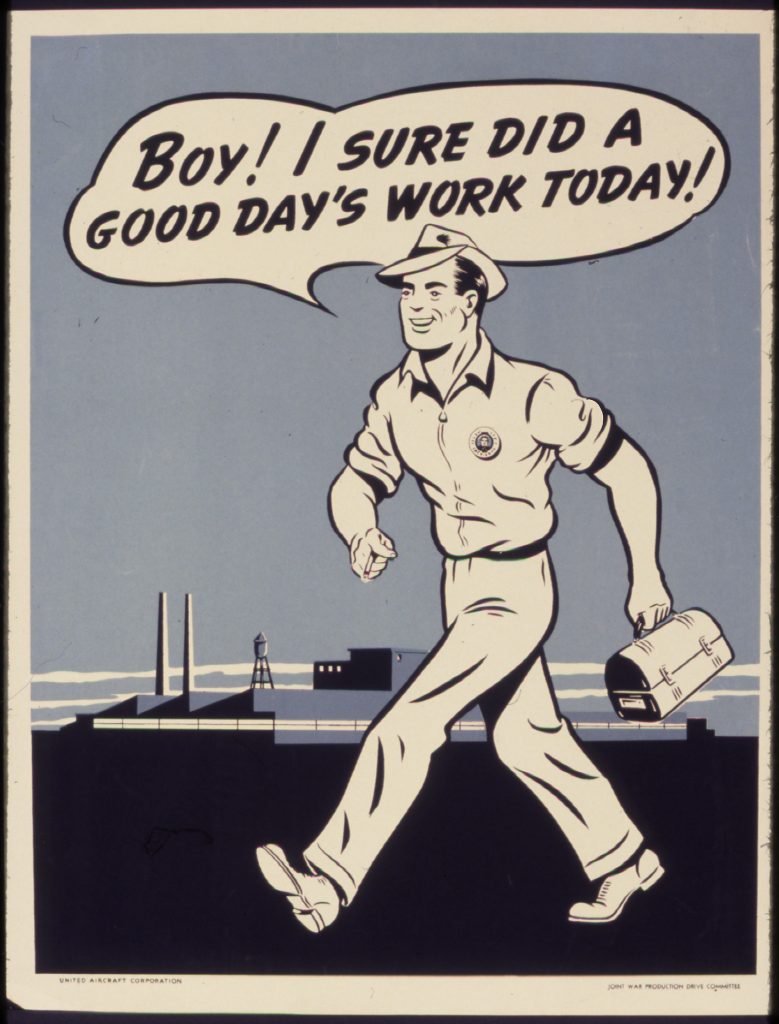

But his story does not stop there. In fact, York himself never considered his wartime exploits to be his most important actions. Returning home, he married and fathered eight children. In the 1920’s, he opened the Alvin C. York Foundation to help poor, rural children get a quality education. He worked in various capacities during the Great Depression, and as a life-long Democrat (normal for that part of the country in those days), supported FDR’s various New Deal organizations. When WWII rolled around, as he was too old and out of shape to actually fight, he was commissioned in the Army Signal Corp. In this role, he toured the country, helping to sell war bonds and encouraging younger men to serve the war effort.

But his story does not stop there. In fact, York himself never considered his wartime exploits to be his most important actions. Returning home, he married and fathered eight children. In the 1920’s, he opened the Alvin C. York Foundation to help poor, rural children get a quality education. He worked in various capacities during the Great Depression, and as a life-long Democrat (normal for that part of the country in those days), supported FDR’s various New Deal organizations. When WWII rolled around, as he was too old and out of shape to actually fight, he was commissioned in the Army Signal Corp. In this role, he toured the country, helping to sell war bonds and encouraging younger men to serve the war effort.

Gen. Matthew Ridgway later recalled that York “created in the minds of farm boys and clerks…the conviction that an aggressive soldier, well-trained and well-armed, can fight his way out of any situation.” He also raised funds for war-related charities, including the Red Cross. He served on his county draft board, and when literacy requirements forced the rejection of large numbers of Fentress County men, he offered to lead a battalion of illiterates himself, saying they were “crack shots.”

He often verbally attacked isolationists and said veterans understood that “liberty and freedom are so very precious that you do not fight and win them once and stop.” They are “prizes awarded only to those peoples who fight to win them and then keep fighting eternally to hold them!” At times he was blunt: “I think any man who talks against the interests of his own country ought to be arrested and put in jail, not excepting senators and colonels.” Everyone knew the colonel in question was Charles Lindbergh. After the war, he even offered to be the one to “push the button” on atomic bombs, if needed, in a first strike against the Soviet Union.

The film about his life was made in 1941, and he used the proceeds, nearly $150,000, to open a Bible School. His latter years were filled with physical infirmities, and he died in 1964. He had been basically confined to his bed after 1954.

So what can we learn from this man that is relevant today? Just like modern Gen Xers, York had a rough childhood, defined by isolation and lack of parental control, resulting in a wild and irreverent youth. However, when the time came for action, he stepped up and did what had to be done. He was not afraid to examine his preconceived notions and alter them when appropriate, whether in his religious views, personal actions, political beliefs, and military service. He used his God-given skills to make a difference, both on the battlefield and in life. He was willing to use all that he had to serve others. He was fair, but unrelenting. He went to extremes, but did so because it was the only way to accomplish those tasks before him.

Not only did he look outside of himself, providing and caring for others, but he raised eight children who carried on his tradition. His oldest son, Thomas Jefferson York, was killed in the line of duty as a Constable. So yes, Gen Xers, we have plenty to learn from such men. They experienced the same sorts of conditions that we did as youngsters. They were faced with tough choices as adults, and they did what had to be done.

Alvin C. York was a true man of action, and a true Man of the West.

And yet, our politicians think of us great unwashed, uneducated Deplorables as, well, deplorable. Pajama Boy, meet Alvin.

Enjoyed this post.

I must add that Colonel Lindbergh was right. It is strange how a pacifist became a warmonger.

https://twitter.com/ConanTCimmerian

https://gab.ai/ConanTCimmerian

History has a circular element, the human terrain is always on top, culture is upstream of politics, liberty is upstream of tyranny, and those who forget the past take the dirt nap first.

Through history Christian Men of The West have been underestimated consistently, only to prove time and time again, no mater how dire events are, they rise to the great tribulations and make fools of all who portend otherwise.

It will be no different this cycle. In fact if anything, we of the West, we get a chance that comes maybe once in an age. There was the 5000 Year Leap, that exceeded all chance, all hubris to the contrary, bested by a mere handful of Men of The West, and won liberty for the first time in all human history.

We get this chance once more, that legacy that was created and handed down to us by the faith, courage, and blood of our founding MOTW, we get this opportunity to not only win, but come out better and larger for it, to leave something even better than was left us.

4.5

5