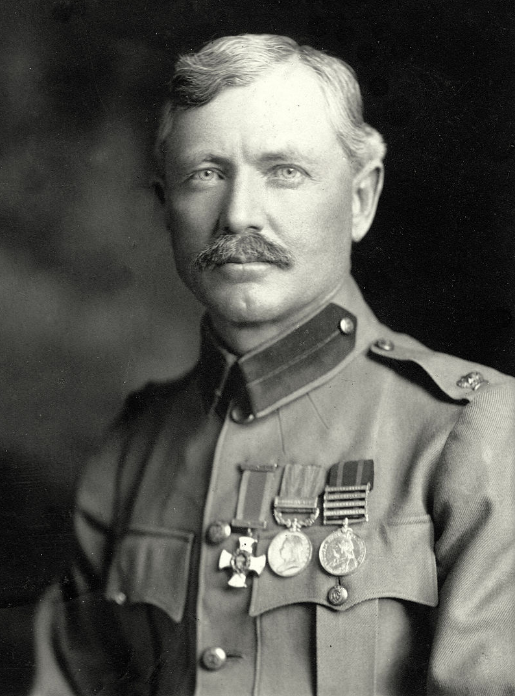

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Real Soldiers of Fortune, by Richard Harding Davis (published 1906)

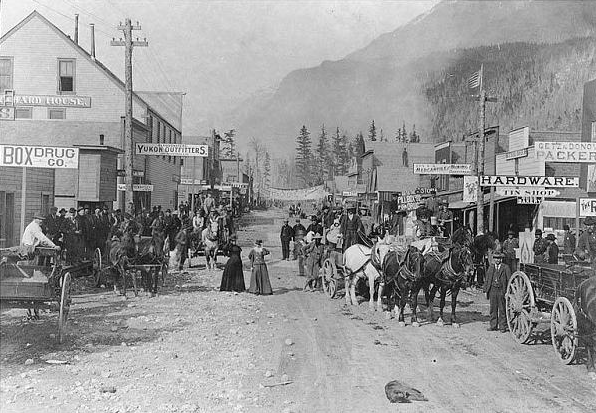

Burnham did not rest long in California. In Alaska the hunt for gold had just begun, and, the old restlessness seizing him, he left Pasadena and her blue skies, tropical plants, and trolley-car strikes for the new raw land of the Klondike. With Burnham it has always been the place that is being made, not the place in being, that attracts. He has helped to make straight the ways of several great communities—Arizona, California, Rhodesia, Alaska, and Uganda. As he once said: “It is the constructive side of frontier life that most appeals to me, the building up of a country, where you see the persistent drive and force of the white man; when the place is finally settled I don’t seem to enjoy it very long.”

In Alaska he did much prospecting, and, with a sled and only two dogs, for twenty-four days made one long fight against snow and ice, covering six hundred miles. In mining in Alaska he succeeded well, but against the country he holds a constant grudge, because it kept him out of the fight with Spain. When war was declared he was in the wilds and knew nothing of it, and though on his return to civilization he telegraphed Colonel Roosevelt volunteering for the Rough Riders, and at once started south, by the time he had reached Seattle the war was over.

Several times has he spoken to me of how bitterly he regretted missing this chance to officially fight for his country. That he had twice served with English forces made him the more keen to show his loyalty to his own people.

That he would have been given a commission in the Rough Riders seems evident from the opinion President Roosevelt has publicly expressed of him.

“I know Burnham,” the President wrote in 1901. “He is a scout and a hunter of courage and ability, a man totally without fear, a sure shot, and a fighter. He is the ideal scout, and when enlisted in the military service of any country he is bound to be of the greatest benefit.”

The truth of this Burnham was soon to prove.

In 1899 he had returned to the Klondike, and in January of 1900 had been six months in Skagway. In that same month Lord Roberts sailed for Cape Town to take command of the army, and with him on his staff was Burnham’s former commander, Sir Frederick, now Lord, Carrington. One night as the ship was in the Bay of Biscay, Carrington was talking of Burnham and giving instances of his marvelous powers as a “tracker.”

“He is the best scout we ever had in South Africa!” Carrington declared.

“Then why don’t we get him back there?” said Roberts.

What followed is well known.

From Gibraltar a cable was sent to Skagway, offering Burnham the position, created especially for him, of chief of scouts of the British army in the field.

Probably never before in the history of wars has one nation paid so pleasant a tribute to the abilities of a man of another nation.

The sequel is interesting. The cablegram reached Skagway by the steamer City of Seattle. The purser left it at the post-office, and until two hours and a half before the steamer was listed to start on her return trip, there it lay. Then Burnham, in asking for his mail, received it. In two hours and a half he had his family, himself, and his belongings on board the steamer, and had started on his half-around-the-world journey from Alaska to Cape Town.

A Skagway paper of January 5, 1900, published the day after Burnham sailed, throws a side light on his character. After telling of his hasty departure the day before, and of the high compliment that had been paid to “a prominent Skagwayan,” it adds: “Although Mr. Burnham has lived in Skagway since last August, and has been North for many months, he has said little of his past, and few have known that he is the man famous over the world as ‘the American scout’ of the Matabele wars.”

Many a man who went to the Klondike did not, for reasons best known to himself, talk about his past. But it is characteristic of Burnham that, though he lived there two years, his associates did not know, until the British Government snatched him from among them, that he had not always been a prospector like themselves.

I was on the same ship that carried Burnham the latter half of his journey, from Southampton to Cape Town, and every night for seventeen nights was one of a group of men who shot questions at him. And it was interesting to see a fellow-countryman one had heard praised so highly so completely make good. It was not as though he had a credulous audience of commercial tourists. Among the officers who each evening gathered around him were Colonel Gallilet of the Egyptian cavalry, Captain Frazer commanding the Scotch Gillies, Captain Mackie of Lord Roberts’s staff, each of whom was later killed in action; Colonel Sir Charles Hunter of the Royal Rifles, Major Bagot, Major Lord Dudley, and Captain Lord Valentia. Each of these had either held command in border fights in India or the Sudan or had hunted big game, and the questions each asked were the outcome of his own experience and observation.

Not for a single evening could a faker have submitted to the midnight examination through which they put Burnham and not have exposed his ignorance. They wanted to know what difference there is in a column of dust raised by cavalry and by trek wagons, how to tell whether a horse that has passed was going at a trot or a gallop, the way to throw a diamond hitch, how to make a fire without at the same time making a target of yourself, how—why—what—and how?

And what made us most admire Burnham was that when he did not know he at once said so.

Within two nights he had us so absolutely at his mercy that we would have followed him anywhere; anything he chose to tell us, we would have accepted. We were ready to believe in flying foxes, flying squirrels, that wild turkeys dance quadrilles—even that you must never sleep in the moonlight. Had he demanded: “Do you believe in vampires?” we would have shouted “Yes.” To ask that a scout should on an ocean steamer prove his ability was certainly placing him under a severe handicap.

As one of the British officers said: “It’s about as fair a game as though we planted the captain of this ship in the Sahara Desert, and told him to prove he could run a ten-thousand-ton liner.”

Burnham continued with Lord Roberts to the fall of Pretoria, when he was invalided home.

During the advance north he was a hundred times inside the Boer laagers, keeping Headquarters Staff daily informed of the enemy’s movements; was twice captured and twice escaped.

He was first captured while trying to warn the British from the fatal drift at Thaba’nchu. When reconnoitering alone in the morning mist he came upon the Boers hiding on the banks of the river, toward which the English were even then advancing. The Boers were moving all about him, and cut him off from his own side. He had to choose between abandoning the English to the trap or signaling to them, and so exposing himself to capture. With the red kerchief the scouts carried for that purpose he wigwagged to the approaching soldiers to turn back, that the enemy were awaiting them. But the column, which was without an advance guard, paid no attention to his signals and plodded steadily on into the ambush, while Burnham was at once made prisoner. In the fight that followed he pretended to receive a wound in the knee and bound it so elaborately that not even a surgeon would have disturbed the carefully arranged bandages. Limping heavily and groaning with pain, he was placed in a trek wagon with the officers who really were wounded, and who, in consequence, were not closely guarded. Burnham told them who he was and, as he intended to escape, offered to take back to head-quarters their names or any messages they might wish to send to their people. As twenty yards behind the wagon in which they lay was a mounted guard, the officers told him escape was impossible. He proved otherwise. The trek wagon was drawn by sixteen oxen and driven by a Kaffir boy. Later in the evening, but while it still was moonlight, the boy descended from his seat and ran forward to belabor the first spans of oxen. This was the opportunity for which Burnham had been waiting.

Slipping quickly over the driver’s seat, he dropped between the two “wheelers” to the disselboom, or tongue, of the trek wagon. From this he lowered himself and fell between the legs of the oxen on his back in the road. In an instant the body of the wagon had passed over him, and while the dust still hung above the trail he rolled rapidly over into the ditch at the side of the road and lay motionless.

It was four days before he was able to re-enter the British lines, during which time he had been lying in the open veldt, and had subsisted on one biscuit and two handfuls of “mealies,” or what we call Indian corn.

Another time when out scouting he and his Kaffir boy while on foot were “jumped” by a Boer commando and forced to hide in two great ant-hills. The Boers went into camp on every side of them, and for two days, unknown to themselves, held Burnham a prisoner. Only at night did he and the Cape boy dare to crawl out to breathe fresh air and to eat the food tablets they carried in their pockets. On five occasions was Burnham sent into the Boer lines with dynamite cartridges to blow up the railroad over which the enemy was receiving supplies and ammunition. One of these expeditions nearly ended his life.

On June 2, 1901, while trying by night to blow up the line between Pretoria and Delagoa Bay, he was surrounded by a party of Boers and could save himself only by instant flight. He threw himself Indian fashion along the back of his pony, and had all but got away when a bullet caught the horse and, without even faltering in its stride, it crashed to the ground dead, crushing Burnham beneath it and knocking him senseless. He continued unconscious for twenty-four hours, and when he came to, both friends and foes had departed. Bent upon carrying out his orders, although suffering the most acute agony, he crept back to the railroad and destroyed it. Knowing the explosion would soon bring the Boers, on his hands and knees he crept to an empty kraal, where for two days and nights he lay insensible. At the end of that time he appreciated that he was sinking and that unless he found aid he would die.

Accordingly, still on his hands and knees, he set forth toward the sound of distant firing. He was indifferent as to whether it came from the enemy or his own people, but, as it chanced, he was picked up by a patrol of General Dickson’s Brigade, who carried him to Pretoria. There the surgeons discovered that in his fall he had torn apart the muscles of the stomach and burst a blood-vessel. That his life was saved, so they informed him, was due only to the fact that for three days he had been without food. Had he attempted to digest the least particle of the “staff of life” he would have surely died. His injuries were so serious that he was ordered home.

On leaving the army he was given such hearty thanks and generous rewards as no other American ever received from the British War Office. He was promoted to the rank of major, presented with a large sum of money, and from Lord Roberts received a personal letter of thanks and appreciation.

In part the Field-Marshal wrote: “I doubt if any other man in the force could have successfully carried out the thrilling enterprises in which from time to time you have been engaged, demanding as they did the training of a lifetime, combined with exceptional courage, caution, and powers of endurance.” On his arrival in England he was commanded to dine with the Queen and spend the night at Osborne, and a few months later, after her death, King Edward created him a member of the Distinguished Service Order, and personally presented him with the South African medal with five bars, and the cross of the D. S. O. While recovering his health Burnham, with Mrs. Burnham, was “passed on” by friends he had made in the army from country house to country house; he was made the guest of honor at city banquets, with the Duke of Rutland rode after the Belvoir hounds, and in Scotland made mild excursions after grouse. But after six months of convalescence he was off again, this time to the hinterland of Ashanti, on the west coast of Africa, where he went in the interests of a syndicate to investigate a concession for working gold mines.

With his brother-in-law, J. C. Blick, he marched and rowed twelve hundred miles, and explored the Volta River, at that date so little visited that in one day’s journey they counted eleven hippopotamuses. In July, 1901, he returned from Ashanti, and a few months later an unknown but enthusiastic admirer asked in the House of Commons if it were true Major Burnham had applied for the post of Instructor of Scouts at Aldershot. There is no such post, and Burnham had not applied for any other post. To the Timer he wrote: “I never have thought myself competent to teach Britons how to fight, or to act as an instructor with officers who have fought in every corner of the world. The question asked in Parliament was entirely without my knowledge, and I deeply regret that it was asked.” A few months later, with Mrs. Burnham and his younger son, Bruce, he journeyed to East Africa as director of the East African Syndicate.

During his stay there the African Review said of him: “Should East Africa ever become a possession for England to be proud of, she will owe much of her prosperity to the brave little band that has faced hardships and dangers in discovering her hidden resources. Major Burnham has chosen men from England, Ireland, the United States, and South Africa for sterling qualities, and they have justified his choice. Not the least like a hero is the retiring, diffident little major himself, though a finer man for a friend or a better man to serve under would not be found in the five continents.”

Burnham explored a tract of land larger than Germany, penetrating a thousand miles through a country, never before visited by white men, to the borders of the Congo Basin. With him he had twenty white men and five hundred natives. The most interesting result of the expedition was the discovery of a lake forty-nine miles square, composed almost entirely of pure carbonate of soda, forming a snowlike crust so thick that on it the men could cross the lake.

It is the largest, and when the railroad is built—the Uganda Railroad is now only eighty-eight miles distant—it will be the most valuable deposit of carbonate of soda ever found.

A year ago, in the interests of John Hays Hammond, the distinguished mining engineer of South Africa and this country, Burnham went to Sonora, Mexico, to find a buried city and to open up mines of copper and silver.

Besides seeking for mines, Hammond and Burnham, with Gardner Williams, another American who also made his fortune in South Africa, are working together on a scheme to import to this country at their own expense many species of South African deer.

The South African deer is a hardy animal and can live where the American deer cannot, and the idea in importing him is to prevent big game in this country from passing away. They have asked Congress to set aside for these animals a portion of the forest reserve. Already Congress has voted toward the plan $15,000, and President Roosevelt is one of its most enthusiastic supporters.

We cannot leave Burnham in better hands than those of Hammond and Gardner Williams. Than these three men the United States has not sent to British Africa any Americans of whom she has better reason to be proud. Such men abroad do for those at home untold good. They are the real ambassadors of their country.

The last I learned of Burnham is told in the snapshot of him which accompanies this article, and which shows him, barefoot, in the Yaqui River, where he has gone, perhaps, to conceal his trail from the Indians. It came a month ago in a letter which said briefly that when the picture was snapped the expedition was “trying to cool off.” There his narrative ended. Promising as it does adventures still to come, it seems a good place in which to leave him.

Meanwhile, you may think of Mrs. Burnham after a year in Mexico keeping the house open for her husband’s return to Pasadena, and of their first son, Roderick, studying woodcraft with his father, forestry with Gifford Pinchot, and playing right guard on the freshman team at the University of California.

But Burnham himself we will leave “cooling off” in the Yaqui River, maybe, with Indians hunting for him along the banks. And we need not worry about him. We know they will not catch him.

5

This is a fabulous write up of a seriously under-appreciated American hero who has intrigued me very much since I first started hearing about his exploits in my native Southern Rhodesia. It is a pity that this narrative uses the now seriously offensive “K” word in reference to some of the people he worked with. At the time it was used casually and not regarded as offensive at all, but now I dare not share the article as widely as I would like. It would be great if the article could be edited to remove that word.

This was a man to admire. As to his modesty, I know another, a cousin of mine who was an elite soldier in the Rhodesian SAS and the legendary Selous Scouts who in some ways rivals Burnham, but now lives far away from Africa. I discovered in visiting him that those who know him and have worked with him since he moved have no idea of his exploits.