Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Real Soldiers of Fortune, by Richard Harding Davis (published 1906)

Among the soldiers of fortune whose stories have been told in this book were men who are no longer living, men who, to the United States, are strangers, and men who were of interest chiefly because in what they attempted they failed.

The subject of this article is none of these. His adventures are as remarkable as any that ever led a small boy to dig behind the barn for buried treasure, or stalk Indians in the orchard. But entirely apart from his adventures he obtains our interest because in what he has attempted he has not failed, because he is one of our own people, one of the earliest and best types of American, and because, so far from being dead and buried, he is at this moment very much alive, and engaged in Mexico in searching for a buried city. For exercise, he is alternately chasing, or being chased by, Yaqui Indians.

In his home in Pasadena, Cal., where sometimes he rests quietly for almost a week at a time, the neighbors know him as “Fred” Burnham. In England the newspapers crowned him “The King of Scouts.” Later, when he won an official title, they called him “Major Frederick Russell Burnham, D. S. O.”

Some men are born scouts, others by training become scouts. From his father Burnham inherited his instinct for wood-craft, and to this instinct, which in him is as keen as in a wild deer or a mountain lion, he has added, in the jungle and on the prairie and mountain ranges, years of the hardest, most relentless schooling. In those years he has trained himself to endure the most appalling fatigues, hunger, thirst, and wounds; has subdued the brain to infinite patience, has learned to force every nerve in his body to absolute obedience, to still even the beating of his heart. Indeed, than Burnham no man of my acquaintance to my knowledge has devoted himself to his life’s work more earnestly, more honestly, and with such single-mindedness of purpose. To him scouting is as exact a study as is the piano to Paderewski, with the result that to-day what the Pole is to other pianists, the American is to all other “trackers,” woodmen, and scouts. He reads “the face of Nature” as you read your morning paper. To him a movement of his horse’s ears is as plain a warning as the “Go SLOW” of an automobile sign; and he so saves from ambush an entire troop. In the glitter of a piece of quartz in the firelight he discovers King Solomon’s mines. Like the horned cattle, he can tell by the smell of it in the air the near presence of water, and where, glaring in the sun, you can see only a bare kopje, he distinguishes the muzzle of a pompom, the crown of a Boer sombrero, the levelled barrel of a Mauser. He is the Sherlock Holmes of all out-of-doors.

Besides being a scout, he is soldier, hunter, mining expert, and explorer. Within the last ten years the educated instinct that as a younger man taught him to follow the trail of an Indian, or the “spoor” of the Kaffir and the trek wagon, now leads him as a mining expert to the hiding-places of copper, silver, and gold, and, as he advises, great and wealthy syndicates buy or refuse tracts of land in Africa and Mexico as large as the State of New York. As an explorer in the last few years in the course of his expeditions into undiscovered lands, he has added to this little world many thousands of square miles.

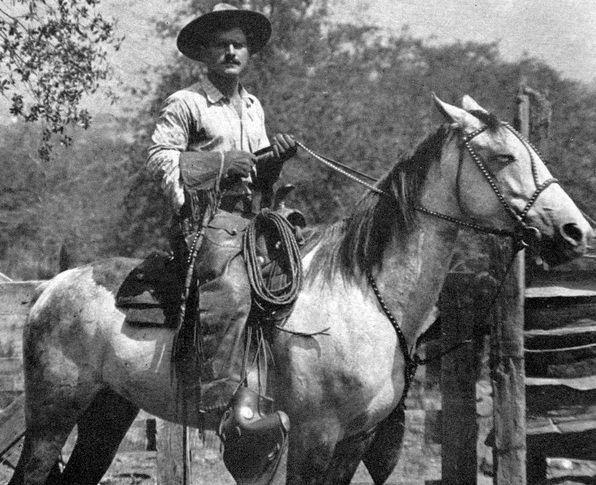

Personally, Burnham is as unlike the scout of fiction, and of the Wild West Show, as it is possible for a man to be. He possesses no flowing locks, his talk is not of “greasers,” “grizzly b’ars,” or “pesky redskins.” In fact, because he is more widely and more thoroughly informed, he is much better educated than many who have passed through one of the “Big Three” universities, and his English is as conventional as though he had been brought up on the borders of Boston Common, rather than on the borders of civilization.

In appearance he is slight, muscular, bronzed; with a finely formed square jaw, and remarkable light blue eyes. These eyes apparently never leave yours, but in reality they see everything behind you and about you, above and below you. They tell of him that one day, while out with a patrol on the veldt, he said he had lost the trail and, dismounting, began moving about on his hands and knees, nosing the ground like a bloodhound, and pointing out a trail that led back over the way the force had just marched. When the commanding officer rode up, Burnham said:

“Don’t raise your head, sit. On that kopje to the right there is a commando of Boers.”

“When did you see them?” asked the officer.

“I see them now,” Burnham answered.

“But I thought you were looking for a lost trail?”

“That’s what the Boers on the kopje think,” said Burnham.

In his eyes, possibly, owing to the uses to which they have been trained, the pupils, as in the eyes of animals that see in the dark, are extremely small. Even in the photographs that accompany this article this feature of his eyes is obvious, and that he can see in the dark the Kaffirs of South Africa firmly believe. In manner he is quiet, courteous, talking slowly but well, and, while without any of that shyness that comes from self-consciousness, extremely modest. Indeed, there could be no better proof of his modesty than the difficulties I have encountered in gathering material for this article, which I have been five years in collecting. And even now, as he reads it by his camp-fire, I can see him squirm with embarrassment.

Burnham’s father was a pioneer missionary in a frontier hamlet called Tivoli on the edge of the Indian reserve of Minnesota. He was a stern, severely religious man, born in Kentucky, but educated in New York, where he graduated from the Union Theological Seminary. He was wonderfully skilled in wood-craft. Burnham’s mother was a Miss Rebecca Russell of a well-known family in Iowa. She was a woman of great courage, which, in those days on that skirmish line of civilization, was a very necessary virtue; and she was possessed of a most gentle and sweet disposition. That was her gift to her son Fred, who was born on May 11, 1861.

His education as a child consisted in memorizing many verses of the Bible, the “Three R’s,” and wood-craft. His childhood was strenuous. In his mother’s arms he saw the burning of the town of New Ulm, which was the funeral pyre for the women and children of that place when they were massacred by Red Cloud and his braves.

On another occasion Fred’s mother fled for her life from the Indians, carrying the boy with her. He was a husky lad, and knowing that if she tried to carry him farther they both would be overtaken, she hid him under a shock of corn. There, the next morning, the Indians having been driven off, she found her son sleeping as soundly as a night watchman. In these Indian wars, and the Civil War which followed, of the families of Burnham and Russell, twenty-two of the men were killed. There is no question that Burnham comes of fighting stock.

In 1870, when Fred was nine years old, his father moved to Los Angeles, Cal., where two years later he died; and for a time for both mother and boy there was poverty, hard and grinding. To relieve this young Burnham acted as a mounted messenger. Often he was in the saddle from twelve to fifteen hours, and even in a land where everyone rode well, he gained local fame as a hard rider. In a few years a kind uncle offered to Mrs. Burnham and a younger brother a home in the East, but at the last moment Fred refused to go with them, and chose to make his own way. He was then thirteen years old, and he had determined to be a scout.

At that particular age many boys have set forth determined to be scouts, and are generally brought home the next morning by a policeman. But Burnham, having turned his back on the cities, did not repent. He wandered over Mexico, Arizona, California. He met Indians, bandits, prospectors, hunters of all kinds of big game; and finally a scout who, under General Taylor, had served in the Mexican War. This man took a liking to the boy; and his influence upon him was marked and for his good. He was an educated man, and had carried into the wilderness a few books. In the cabin of this man Burnham read “The Conquest of Mexico and Peru” by Prescott, the lives of Hannibal and Cyrus the Great, of Livingstone the explorer, which first set his thoughts toward Africa, and many technical works on the strategy and tactics of war. He had no experience of military operations on a large scale, but, with the aid of the veteran of the Mexican War, with corn-cobs in the sand in front of the cabin door, he constructed forts and made trenches, redoubts, and traverses. In Burnham’s life this seems to have been a very happy period. The big game he hunted and killed he sold for a few dollars to the men of Nadean’s freight outfits, which in those days hauled bullion from Cerro Gordo for the man who is now Senator Jones of Nevada.

At nineteen Burnham decided that there were things in this world he should know that could not be gleaned from the earth, trees, and sky; and with the few dollars he had saved he came East. The visit apparently was not a success. The atmosphere of the town in which he went to school was strictly Puritanical, and the townspeople much given to religious discussion. The son of the pioneer missionary found himself unable to subscribe to the formulas which to the others seemed so essential, and he returned to the West with the most bitter feelings, which lasted until he was twenty-one.

“It seems strange now,” he once said to me, “but in those times religious questions were as much a part of our daily life as today are automobiles, the Standard Oil, and the insurance scandals, and when I went West I was in an unhappy, doubting frame of mind. The trouble was I had no moral anchors; the old ones father had given me were gone, and the time for acquiring new ones had not arrived.” This bitterness of heart, or this disappointment, or whatever the state of mind was that the dogmas of the New England town had inspired in the boy from the prairie, made him reckless. For the life he was to lead this was not a handicap. Even as a lad, in a land-grant war in California, he had been under gunfire, and for the next fifteen years he led a life of danger and of daring; and studied in a school of experience than which, for a scout, if his life be spared, there can be none better. Burnham came out of it a quiet, manly, gentleman. In those fifteen years he roved the West from the Great Divide to Mexico. He fought the Apache Indians for the possession of waterholes, he guarded bullion on stage-coaches, for days rode in pursuit of Mexican bandits and American horse thieves, took part in county-seat fights, in rustler wars, in cattle wars; he was cowboy, miner, deputy-sheriff, and in time throughout the the name of “Fred” Burnham became significant and familiar.

During this period Burnham was true to his boyhood ideal of becoming a scout. It was not enough that by merely living the life around him he was being educated for it. He daily practised and rehearsed those things which some day might mean to himself and others the difference between life and death. To improve his sense of smell he gave up smoking, of which he was extremely fond, nor, for the same reason, does he to this day use tobacco. He accustomed himself also to go with little sleep, and to subsist on the least possible quantity of food. As a deputy-sheriff this educated faculty of not requiring sleep aided him in many important captures. Sometimes he would not strike the trail of the bandit or “bad man” until the other had several days the start of him. But the end was the same; for, while the murderer snatched a few hours’ rest by the trail, Burnham, awake and in the saddle, would be closing up the miles between them.

That he is a good marksman goes without telling. At the age of eight his father gave him a rifle of his own, and at twelve, with either a “gun” or a Winchester, he was an expert. He taught himself to use a weapon either in his left or right hand and to shoot, Indian fashion, hanging by one leg from his pony and using it as a cover, and to turn in the saddle and shoot behind him. I once asked him if he really could shoot to the rear with a galloping horse under him and hit a man.

“Well,” he said, “maybe not to hit him, but I can come near enough to him to make him decide my pony’s so much faster than his that it really isn’t worthwhile to follow me.”

Besides perfecting himself in what he tolerantly calls “tricks” of horsemanship and marksmanship, he studied the signs of the trail, forest and prairie, as a sailing-master studies the waves and clouds. The knowledge he gathers from inanimate objects and dumb animals seems little less than miraculous. And when you ask him how he knows these things he always gives you a reason founded on some fact or habit of nature that shows him to be a naturalist, mineralogist, geologist, and botanist, and not merely a seventh son of a seventh son.

In South Africa he would say to the officers: “There are a dozen Boers five miles ahead of us riding Basuto ponies at a trot, and leading five others. If we hurry we should be able to sight them in an hour.” At first the officers would smile, but not after a half-hour’s gallop, when they would see ahead of them a dozen Boers leading five ponies. In the early days of Salem, Burnham would have been burned as a witch.

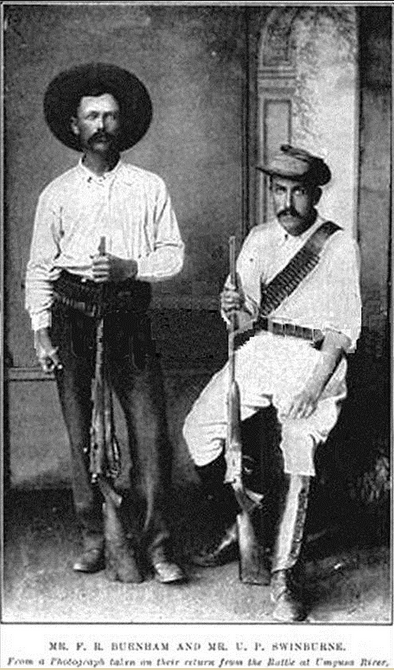

When twenty-three years of age he married Miss Blanche Blick, of Iowa. They had known each other from childhood, and her brothers-in-law have been Burnham’s aids and companions in every part of Africa and the West. Neither at the time of their marriage nor since did Mrs. Burnham “lay a hand on the bridle rein,” as is witnessed by the fact that for nine years after his marriage Burnham continued his career as sheriff, scout, mining prospector. And in 1893, when Burnham and his brother-in-law, Ingram, started for South Africa, Mrs. Burnham went with them, and in every part of South Africa shared her husband’s life of travel and danger.

In making this move across the sea, Burnham’s original idea was to look for gold in the territory owned by the German East African Company. But as in Rhodesia the first Matabele uprising had broken out, he continued on down the coast, and volunteered for that campaign. This was the real beginning of his fortunes. The “war” was not unlike the Indian fighting of his early days, and although the country was new to him, with the kind of warfare then being waged between the Kaffirs under King Lobengula and the white settlers of the British South Africa Company, the chartered company of Cecil Rhodes, he was intimately familiar.

It does not take big men long to recognize other big men, and Burnham’s remarkable work as a scout at once brought him to the notice of Rhodes and Dr. Jameson, who was personally conducting the campaign. The war was their own private war, and to them, at such a crisis in the history of their settlement, a man like Burnham was invaluable.

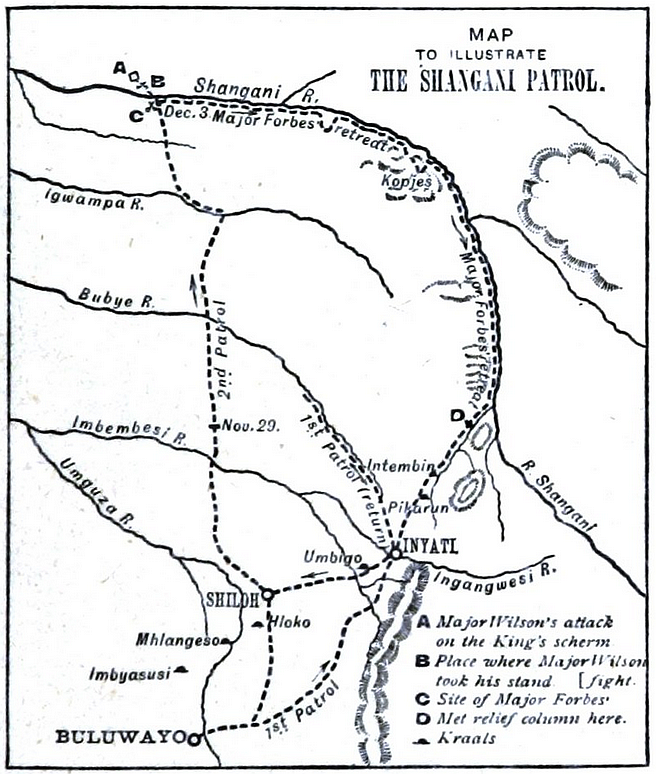

The chief incident of this campaign, the fame of which rang over all Great Britain and her colonies, was the gallant but hopeless stand made by Major Alan Wilson and his patrol of thirty-four men. It was Burnham’s attempt to save these men that made him known from Buluwayo to Cape Town.

King Lobengula and his warriors were halted on one bank of the Shangani River, and on the other Major Forbes, with a picked force of three hundred men, was coming up in pursuit. Although at the moment he did not know it, he also was being pursued by a force of Matabeles, who were gradually surrounding him. At nightfall Major Wilson and a patrol of twelve men, with Burnham and his brother-in-law, Ingram, acting as scouts, were ordered to make a dash into the camp of Lobengula and, if possible, in the confusion of their sudden attack, and under cover of a terrific thunder-storm that was raging, bring him back a prisoner.

With the king in their hands the white men believed the rebellion would collapse. To the number of three thousand the Matabeles were sleeping in a succession of camps, through which the fourteen men rode at a gallop. But in the darkness it was difficult to distinguish the trek wagon of the king, and by the time they found his laager the Matabeles from the other camps through which they had ridden had given the alarm. Through the underbrush from every side the enemy, armed with assegai and elephant guns, charged toward them and spread out to cut off their retreat.

At a distance of about seven hundred yards from the camps there was a giant ant-hill, and the patrol rode toward it. By the aid of the lightning flashes they made their way through a dripping wood and over soil which the rain had turned into thick black mud. When the party drew rein at the ant-hill it was found that of the fourteen three were missing. As the official scout of the patrol and the only one who could see in the dark, Wilson ordered Burnham back to find them. Burnham said he could do so only by feeling the hoof-prints in the mud and that he would like someone with him to lead his pony. Wilson said he would lead it. With his fingers Burnham followed the trail of the eleven horses to where, at right angles, the hoof-prints of the three others separated from it, and so came upon the three men. Still, with nothing but the mud of the jungle to guide him, he brought them back to their comrades. It was this feat that established his reputation among British, Boers, and black men in South Africa.

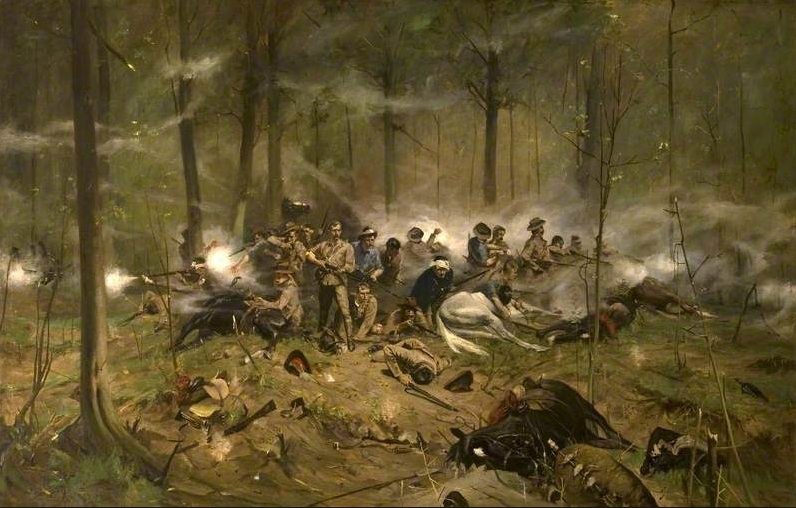

Throughout the night the men of the patrol lay in the mud holding the reins of their horses. In the jungle about them, they could hear the enemy splashing through the mud, and the swishing sound of the branches as they swept back into place. It was still raining. Just before the dawn there came the sounds of voices and the welcome clatter of accoutrements. The men of the patrol, believing the column had joined them, sprang up rejoicing, but it was only a second patrol, under Captain Borrow, who had been sent forward with twenty men as re-enforcements. They had come in time to share in a glorious immortality. No sooner had these men joined than the Kaffirs began the attack; and the white men at once learned that they were trapped in a complete circle of the enemy. Hidden by the trees, the Kaffirs fired point-blank, and in a very little time half of Wilson’s force was killed or wounded. As the horses were shot down the men used them for breastworks. There was no other shelter. Wilson called Burnham to him and told him he must try and get through the lines of the enemy to Forbes.

“Tell him to come up at once,” he said; “we are nearly finished.” He detailed a trooper named Gooding and Ingram to accompany Burnham. “One of you may get through,” he said. Gooding was but lately out from London, and knew nothing of scouting, so Burnham and Ingram warned him, whether he saw the reason for it or not, to act exactly as they did. The three men had barely left the others before the enemy sprang at them with their spears. In five minutes they were being fired at from every bush. Then followed a remarkable ride, in which Burnham called to his aid all he had learned in thirty years of border warfare. As the enemy rushed after them, the three doubled on their tracks, rode in triple loops, hid in dongas to breathe their horses; and to scatter their pursuers, separated, joined again, and again separated. The enemy followed them to the very bank of the river, where, finding the “drift” covered with the swollen waters, they were forced to swim. They reached the other bank only to find Forbes hotly engaged with another force of the Matabeles.

“I have been sent for re-enforcements,” Burnham said to Forbes, “but I believe we are the only survivors of that party.” Forbes himself was too hard pressed to give help to Wilson, and Burnham, his errand over, took his place in the column, and began firing upon the new enemy.

Six weeks later the bodies of Wilson’s patrol were found lying in a circle. Each of them had been shot many times. A son of Lobengula, who witnessed their extermination, and who in Buluwayo had often heard the Englishmen sing their national anthem, told how the five men who were the last to die stood up and, swinging their hats defiantly, sang “God Save the Queen.” The incident will long be recorded in song and story; and in London was reproduced in two theatres, in each of which the man who played “Burnham, the American Scout,” as he rode off for re-enforcements, was as loudly cheered by those in the audience as by those on the stage.

Hensman, in his “History of Rhodesia,” says: “One hardly knows which to most admire, the men who went on this dangerous errand, through brush swarming with natives, or those who remained behind battling against overwhelming odds.”

For his help in this war the Chartered Company presented Burnham with the campaign medal, a gold watch engraved with words of appreciation; and at the suggestion of Cecil Rhodes gave him, Ingram, and the Hon. Maurice Clifford, jointly, a tract of land of three hundred square acres.

After this campaign Burnham led an expedition of ten white men and seventy Kaffirs north of the Zambesi River to explore Barotzeland and other regions to the north of Mashonaland, and to establish the boundaries of the concession given him, Ingram, and Clifford.

In order to protect Burnham on the march the Chartered Company signed a treaty with the native king of the country through which he wished to travel, by which the king gave him permission to pass freely and guaranteed him against attack.

But Latea, the son of the king, refused to recognize the treaty and sent his young men in great numbers to surround Burnham’s camp. Burnham had been instructed to avoid a fight, and was torn between his desire to obey the Chartered Company and to prevent a massacre. He decided to make it a sacrifice either of himself or of Latea. As soon as night fell, with only three companions and a missionary to act as a witness of what occurred, he slipped through the lines of Latea’s men, and, kicking down the fence around the prince’s hut, suddenly appeared before him and covered him with his rifle.

“Is it peace or war?” Burnham asked. “I have the king your father’s guarantee of protection, but your men surround us. I have told my people if they hear shots to open fire. We may all be killed, but you will be the first to die.”

The missionary also spoke urging Latea to abide by the treaty. Burnham says the prince seemed much more impressed by the arguments of the missionary than by the fact that he still was covered by Burnham’s rifle. Whichever argument moved him, he called off his warriors. On this expedition Burnham discovered the ruins of great granite structures fifteen feet wide, and made entirely without mortar. They were of a period dating before the Phoenicians. He also sought out the ruins described to him by F. C. Selous, the famous hunter, and by Rider Haggard as King Solomon’s Mines. Much to the delight of Mr. Haggard, he brought back for him from the mines of his imagination real gold ornaments and a real gold bar.

On this same expedition, which lasted five months, Burnham endured one of the severest hardships of his life. Alone with ten Kaffir boys, he started on a week’s journey across the dried-up basin of what once had been a great lake. Water was carried in goat-skins on the heads of the bearers. The boys, finding the bags an unwieldy burden, and believing, with the happy optimism of their race, that Burnham’s warnings were needless, and that at a stream they soon could refill the bags, emptied the water on the ground.

The tortures that followed this wanton waste were terrible. Five of the boys died, and after several days, when Burnham found water in abundance, the tongues of the others were so swollen that their jaws could not meet.

On this trip Burnham passed through a region ravaged by the “sleeping sickness,” where his nostrils were never free from the stench of dead bodies, where in some of the villages, as he expressed it, “the hyenas were mangy with overeating, and the buzzards so gorged they could not move out of our way.” From this expedition he brought back many ornaments of gold manufactured before the Christian era, and made several valuable maps of hitherto uncharted regions. It was in recognition of the information gathered by him on this trip that he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

He returned to Rhodesia in time to take part in the second Matabele rebellion. This was in 1896. By now Burnham was a very prominent member of the “vortrekers” and pioneers at Buluwayo, and Sir Frederick Carrington, who was in command of the forces, attached him to his staff. This second outbreak was a more serious uprising than the one of 1893, and as it was evident the forces of the Chartered Company could not handle it, imperial troops were sent to assist them. But with even their aid the war dragged on until it threatened to last to the rainy season, when the troops must have gone into winter quarters. Had they done so, the cost of keeping them would have fallen on the Chartered Company, already a sufferer in pocket from the ravages of the rinderpest and the expenses of the investigation which followed the Jameson raid.

Accordingly, Carrington looked about for some measure by which he could bring the war to an immediate end.

It was suggested to him by a young Colonial, named Armstrong, the Commissioner of the district, that this could be done by destroying the “god,” or high priest, Umlimo, who was the chief inspiration of the rebellion.

This high priest had incited the rebels to a general massacre of women and children, and had given them confidence by promising to strike the white soldiers blind and to turn their bullets into water. Armstrong had discovered the secret hiding-place of Umlimo, and Carrington ordered Burnham to penetrate the enemy’s lines, find the god, capture him, and if that were not possible to destroy him.

The adventure was a most desperate one. Umlimo was secreted in a cave on the top of a huge kopje. At the base of this was a village where were gathered two regiments, of a thousand men each, of his fighting men.

For miles around this village the country was patrolled by roving bands of the enemy.

Against a white man reaching the cave and returning, the chances were a hundred to one, and the difficulties of the journey are illustrated by the fact that Burnham and Armstrong were unable to move faster than at the rate of a mile an hour. In making the last mile they consumed three hours. When they reached the base of the kopje in which Umlimo was hiding, they concealed their ponies in a clump of bushes, and on hands and knees began the ascent.

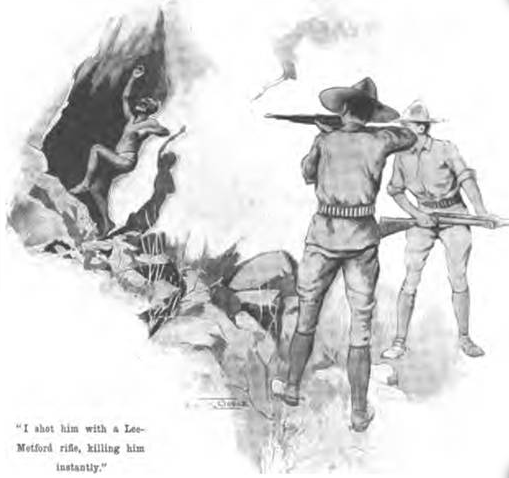

Directly below them lay the village, so close that they could smell the odors of cooking from the huts, and hear, rising drowsily on the hot, noonday air, voices of the warriors. For minutes at a time they lay as motionless as the granite boulders around or squirmed and crawled over loose stones which a miss of hand or knee would have dislodged and sent clattering into the village. After an hour of this tortuous climbing the cave suddenly opened before them, and they beheld Umlimo. Burnham recognized that to take him alive from his stronghold was an impossibility, and that even they themselves would leave the place was equally doubtful. So, obeying orders, he fired, killing the man who had boasted he would turn the bullets of his enemies into water. The echo of the shot aroused the village as would a stone hurled into an ant-heap. In an instant the veldt below was black with running men, and as, concealment being no longer possible, the white men rose to fly a great shout of anger told them they were discovered. At the same moment two women, returning from a stream where they had gone for water, saw the ponies, and ran screaming to give the alarm. The race that followed lasted two hours, for so quickly did the Kaffirs spread out on every side that it was impossible for Burnham to gain ground in any one direction, and he was forced to dodge, turn, and double. At one time the white men were driven back to the very kopje from which the race had started.

But in the end they evaded assegai and gunfire, and in safety reached Buluwayo. This exploit was one of the chief factors in bringing the war to a close. The Matabeles, finding their leader was only a mortal like themselves, and so could not, as he had promised, bring miracles to their aid, lost heart, and when Cecil Rhodes in person made overtures of peace, his terms were accepted. During the hard days of the siege, when rations were few and bad, Burnham’s little girl, who had been the first white child born in Buluwayo, died of fever and lack of proper food. This with other causes led him to leave Rhodesia and return to California. It is possible he then thought he had forever turned his back on South Africa, but, though he himself had departed, the impression he had made there remained behind him.

5