Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Joe Foss, Flying Marine: The Story of His Flying Circus as told to Walter Simmons (published 1943).

The Japs did some queer things sometimes. I don’t know whether you’d call it bravery or foolishness.

Early one day a Mitsubishi reconnaissance bomber—a slick-looking, two-engined job that moves along pretty fast[1] —came over Guadalcanal and took pictures. Our anti-aircraft fired and missed.

The Jap circled wide, then dove and came in, apparently to strafe the field and prove how much nerve he had. He roared impudently down the runway almost on the ground, and every man on the field that could lay his hand on a pistol, rifle, or .50-caliber machine gun cut loose at him from foxholes. Several hits were scored — I saw some on the wings especially.

Anyway, the bomber did a steep wingover, drove straight into the ground behind the trees and exploded. Pieces of three bodies were found and no more. I saw one of our men trying to get a boot off a leg for a souvenir. Others found a .32 Colt revolver and a saber in the wreckage.

Our boys developed an amused contempt for Jap flyers, at the same time respecting the Zero for its good qualities. On the ground we looked up and laughed as the enemy showed off by putting on an aerial circus. “Look at the crazy dopes!” was our response to the slow rolls, wingovers and intricate loops.

With all their sophomoric aerobatics the Zeros reminded me of dogs running across the fields on a spring day. One raced in front with his tongue hanging out, and the others followed, doing wingovers and loops and all sorts of crazy things. They wandered all over the sky, never assembling in formations.

Because of uninspired tactical training, they passed up a lot of good chances in combat — chances our boys knew how to cash in on. They seemed to be following some kind of secret code which allowed of no deviation, like a system for beating the bank at Monte Carlo. Our tactics, on the other hand, were completely elastic; we were always improvising.

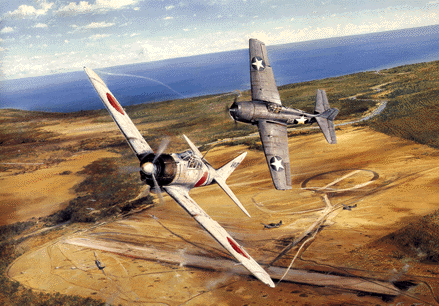

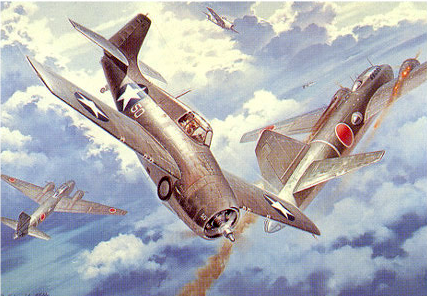

But you couldn’t laugh at the Zero itself. In its peculiar way, it was the best fighting plane in the world at that time. It had our Wildcats beat in interception, maneuverability, climb, and speed. It could turn on a dime, and it could climb like a scared monkey on a rope. I could take any one of my pilots and put him in a Zero, and he would shoot the hell out of me in no time.

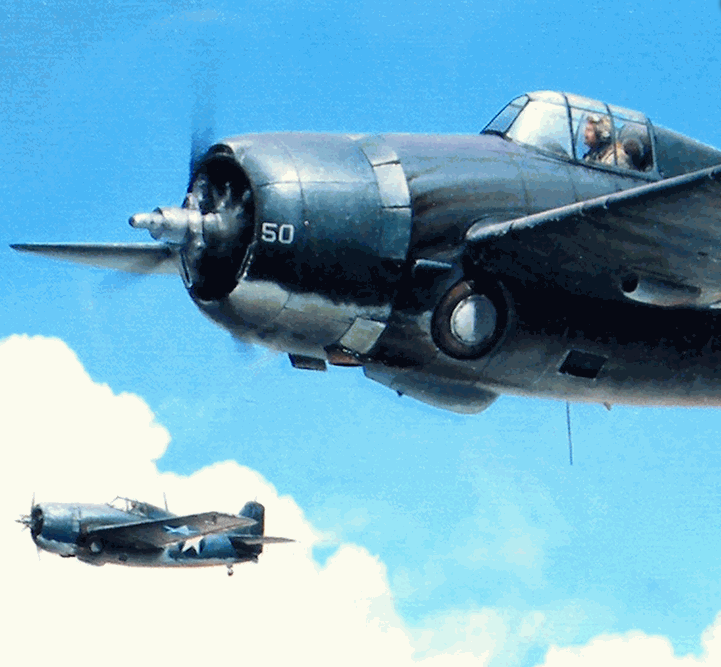

But actually, of course, none of our boys cared to ride in a Zero. They were too vulnerable. Hit right, they exploded or torched. Our Grummans were almost completely proof against fire and explosion. They were also well armored. Back of the seat was heavy protective armor, cut the shape of a man and capable of stopping anything the Japs threw at us. This was a very comforting feature in a dog fight. The Grummans had superior firepower too — more than we really needed. Six converging streams of .50-caliber bullets, fired by a delicate trigger on the control stick, ripped apart anything they touched. Often I conserved ammunition by cutting out two guns and using only four. We learned the value of going easy on ammunition — running out at critical times cost me at least four planes which were helpless in my sights at one time or another.

We worked out many combat tactics for ourselves on Guadalcanal, adding them to the solid foundation we got in school, and from talking to veteran naval pilots who had seen action earlier in the war. We soon learned the value of working in close before doing our shooting. We got better results that way.

We also got wise to the value of little things—such as keeping our planes clean inside and out. Dirt on the outside cuts knots off a ship’s speed. It also conceals bullet holes and mechanical faults that otherwise would be as plain as the teeth in a Jap’s face. Inside, dirt is dangerous because in maneuvering a pilot might get an eyeful right in the middle of a dogfight. The windshield, particularly, should be spotless.

Colonel Bauer had a positive, hard-hitting philosophy of air combat that always tickled me. Many of his ideas have since been incorporated into the new manuals. He formed his theories on the spot at Guadalcanal from watching combat results and questioning us when we returned from fights.

I can see him yet as he pounded those ideas home untiringly. “A successful fighter pilot must be aggressive…. He is not the kind of a man who will turn tail and run. Pilots who do that get their rear extremities full of arrows…. We must all realize the Zero pilot isn’t such a smart guy, or he would take better advantage of his speed, climb, and maneuverability…. Our pilots must avoid getting separated from formations at all costs. We’ll have to give them credit — the Japs have a deadly way of knocking down stragglers.

“Aim for the wing base on all Japanese planes. That’s the best target. None of their planes has armor or self-sealing tanks….

“Be an aggressor. Your job is to shoot down Japanese planes. Outsmart the enemy. You should have complete faith in your armor and confidence in your ability to shoot down any plane you see when you get it in your sights….

“So you want a safe war? There’s no way to make war safe. The thing for you to do is to make it very unsafe for the enemy.”

I am not revealing a tactical secret when I say we grew fond of going at the Zeros head on, as if attempting to ram them. The superior ruggedness of our Wildcats made this possible. Japs knew a collision was suicide and were also afraid of our devastating firepower. On a head-on approach we usually got a good shot, too, when the Zero slow rolled, looped, or made a climbing turn to avoid our attack.

Tail shots, of course, were most productive of results when we could surprise the Zeros. Deflection shooting, from the side, was a difficult test of marksmanship. It amuses me to read reports that this is a “new science.” It is as old as air fighting itself — in fact it’s the same thing as shooting a pheasant on the fly.

The Jap attacks developed a more or less regular pattern. High-level bombers were always escorted by Zeros, the number varying from half a dozen to two dozen, apparently dependent on the number they had on hand. Most of the escort force came in several thousand feet above the bombardment formation, but there was always a smaller group somewhere around, doing playful maneuvers and loops. The reason for this eccentric behavior we never knew — maybe they did it so they could keep watch in all directions. Often the Zeros left cloud trails which remained in the sky like insolent messages for several minutes.

How the enemy replaced his plane losses was a mystery. Certainly they were heavy. Yet he sent his Zeros over almost endlessly. After a time the strain showed, not in planes but in pilots. They were obviously less experienced, less well grounded in tactics. “The second team,” Marines called them.

On the twenty-sixth of October, anti-aircraft gunners pointed out with some pride that they had shot down twenty-six planes during the month — one for every day. This was roughly one for every eight shot down by fighter planes and represented a highly effective showing. The virtuosity of these gunners, many of them veterans of Pearl Harbor and Midway, took a heavy load off our shoulders. Don’t think we didn’t appreciate it.

Big booms from the ground fighting kept us awake during this dangerous period. On Monday no Jap planes showed up — the enemy stayed home licking his wounds of the day before. Again I walked up to the front lines to see the good Japs — dead ones — that had collected overnight.

After a big battle, ground troops had Jap flags, sabers, money, pistols, rifles, and pictures to trade. Pilots used candy, cigarettes, cigars, even watches, for trading stock. Money had little value. One flyer gave a can of chicken, a can of beans, and a towel for a Jap rifle. Most of the men had bracelets made of metal from fallen Zeros.

The disposal of enemy dead was such a problem that engineers blasted a cliff near the Matanikau River to cover a heap of bodies at its foot. Captured Jap equipment included flame throwers, mortars, anti-tank guns, and devices for purifying water. Most significant, however, were American tommy guns of a type used on Bataan. That made our boys see red.

For hours I talked with Captain Ben Finney of New York City about hunting. Many of the pilots were young men who loved hunting. To them Zeros were just like ducks — except that they shot back. Ben told of his big-game hunting trips all over the world, and I talked about South Dakota ducks, pheasants, and the trapping out there. We talked endlessly about guns, which I love.

It wasn’t until later that we heard of the big naval air battle off the Santa Cruz Islands. This had an important bearing on the defense of Guadalcanal. It was expensive for both sides — we lost the Hornet, and the Japs lost 104 planes besides some ships. But for our side it was worth the cost. The appearance of two Jap task forces off the Stewart Islands and the New Hebrides October 26 was a screening action to permit battleships to move in for a second bombardment of our positions, while land forces made a grand mass assault.

The Jap troops on Guadalcanal fought bravely and well, but their naval forces and flyers let them down. The battle of Santa Cruz wrecked one part of the plan by putting their warships to flight. We were able to do our share by giving a decisive beating to their air support at a time when it was critically needed. I don’t think they counted on the toughness of our ground troops, either. Between October 22 and 27 they lost 2,000 men in attacks which gained no ground. On that latter date, on an island twenty-five miles wide and eighty-five miles long, we occupied a little stretch only three miles deep and six miles long.

That day, for the last time, Jap attacks pierced our lines south of the airfield. Again the enemy was driven back. Artillery shells dropped here and there on the field. Our planes bombed enemy gun positions west of the field, destroying an AA battery and an ammunition dump.

With the backbone of the enemy attack broken, both sides were glad of a breathing spell, and the remainder of October was quiet. Small flights of Zeros came over occasionally. Eight were knocked down one day with the loss of one plane for us.

Another day we went to meet an enemy flight but it turned and fled, so no contact was made. The Japs had grown timid after our big weekend. Sometimes high-altitude bombers came over during the night or early in the morning.

Twice Marine flights raided the Jap base at Rekata Bay. The first time four float biplanes and two Zero floats were found on the water. Four of them were left burning and the others so riddled as to be useless.

Two days later Colonel Bauer (he was called “the Coach” by the team-minded pilots) lined up a surprise attack. Arriving at 4:15, just as dawn was lifting, a flight led by Cowboy Stout found the bay covered with float monoplanes and biplanes. “Let ’em get up off the water,” the Cowboy commanded. “Then we can count ’em in our score.” Our flyers, I might explain, do not count planes destroyed on the ground or water.

In fierce action over the bay Conger got a monoplane and a biplane. Three others bagged a Zero apiece. Stout happened to be first back at the field. He was sad as ship after ship came in. “They got one of our boys,” he said. “I saw a Grumman crash headlong into the water with a Zero on its tail.”

Soon all the Grummans were back. Stout was amazed. The only explanation was that one Zero had shot another down in the darkness.

Drury was exasperated when he found his wings laced with .50-caliber bullet holes. “What are you guys trying to do?” he raved. “Kill me?”

The morning’s work brought Conger’s combat score to ten planes and half a destroyer. The Coach had ten planes and a “smoker” which he had not seen crash and characteristically refused to count. These were the best scores in that squadron. Captain Everton had eight planes, the missing Tex Hamilton seven, Major Payne six, Stout and Drury five apiece, and the others lesser numbers. Lieutenant Dick Haring, Muskegon, Michigan, had been killed without claiming a victim, and Chamberlain, shot down twice and wounded once, likewise had a clean slate. The squadron score was ninety-one planes.

After dark every night we all sat on benches around a square table in the bivouac area, smoking, telling stories, and drinking sparingly of whisky, brandy, strong Australian beer, or fruit juice — whichever was available, in that order of preference. Relaxed, the men turned in from eight to eleven o’clock, as they chose. Nobody read at night. There were few flashlights. Nightly blackouts were not observed, but if approaching planes were heard, every light was doused in an instant.

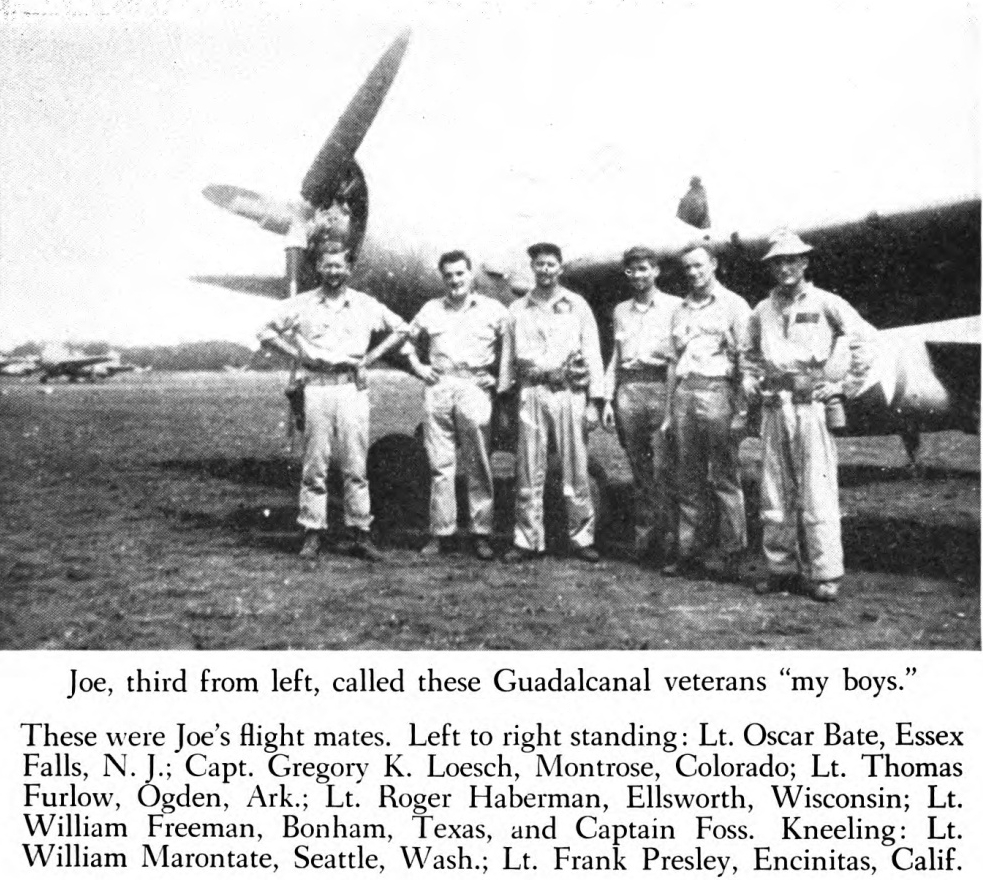

The question of what we were fighting for never was raised in those sessions around the table at night, but there were plenty of indirect answers. The boys had different reasons. Haberman wanted to “go home, lie around, and listen to the grass grow” in Wisconsin. Brandon wanted to get the Japs licked so he could go home and hunt deer. Loesch and Freeman liked the idea of deer hunting, too, but added trout fishing to their list.

Some of the other boys had different ideas—they were fighting for personal satisfaction, for fun, or for lower taxes. But mostly they just wanted to go home, get married, and continue doing the things they’d always enjoyed.

It was pretty much that way with me. I wanted to help keep my country the way it was—a place where some day June and I could own a ranch and live the way we wanted to, working, hunting, fishing, and maybe some day rearing a little family.

Outside of combat there were few high spots in our lives. A letter from home, a sliver of ice from the ten-pound cake the ice plant disgorged each night, a shower to ease the intolerable heat, a gratifying news bulletin from the wireless — these were minor climaxes of existence.

In the absence of dogfights the big events were such things as the arrival of fresh meat or beer. When we had steak for evening chow, it called for a celebration. Once my flight of eight got five bottles of beer, brought off a ship. Some boys don’t like that Australian beer, but I do. It has some body to it.

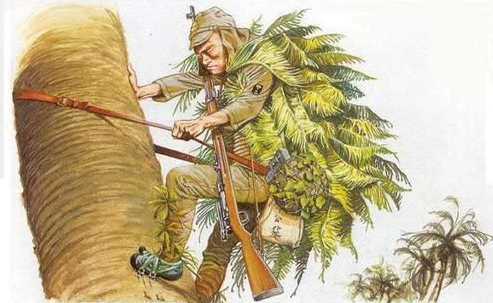

On visits to the front lines, I often marveled at the endurance of our ground fighters. Sometimes the smell of rotting enemy bodies was past description. When bodies lay in front of dense jungle, they could not be reached for burial, because snipers would pick off anyone who approached.

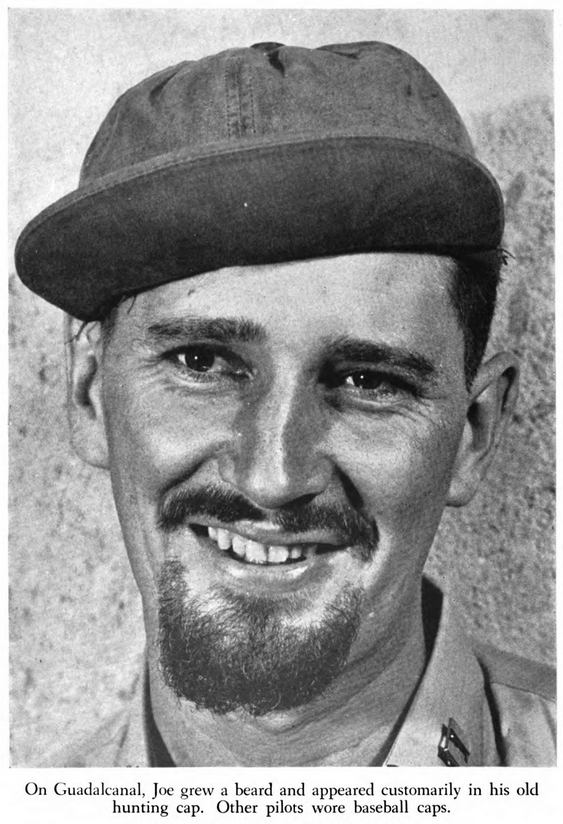

I went hunting for snipers with some of the boys, in spite of Colonel Bauer’s objection. “Too dangerous!” he snorted — a remark that made us laugh. It was a hot day — so sultry that I came near passing out. I became separated from the rest and soon heard one of the men cut loose with his tommy gun. I yelled and asked if he had anything. He said he saw a bush move but did not see anything. That was enough for me — I left. This was about two hundred yards from the field.

Snipers often slipped through the lines and fired at our mechanics at work on the field. Many of these Japs were terrible shots, but sometimes our mechanics would get sore, grab up guns, and take to the woods for a sniper hunt. One big husky fellow with the build of a wrestler — we called him “Dude”— didn’t bother to take a gun. He slipped into the woods one day after being fired on too many times. He found the Jap and killed him with a knife. When he returned, he had an entire Jap outfit, and he was covered with blood as if he had butchered a hog.

______________________

[1] Probably a Mitsubishi Ki-46 “Dinah.” (ed.)