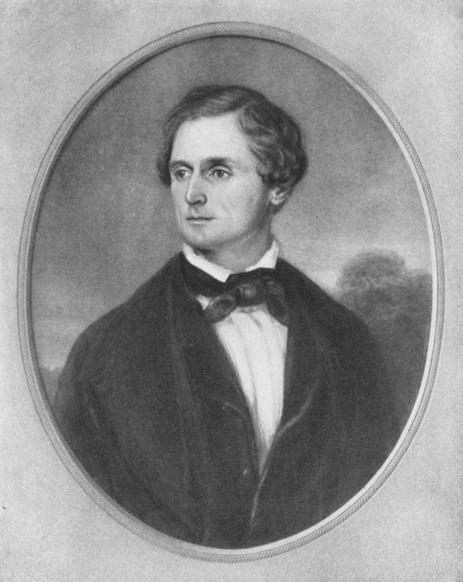

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Not All Warriors: 19th Century West Pointers Who Gained Fame in Other Than Military Fields, by William Baumer, Jr. (published 1941).

There were many sides to the character of Jefferson Davis, but this inquiry will be directed toward that side through which ran the thread of the soldier attacking the political problems of his nation. Clemenceau, the old fox of French politics, declared: “War is much too important a business to be left to soldiers.” It is an interesting question as to how much of war and of military strategy a statesman should know.

Statesmen with little knowledge of military strategy who tried in varying degree to control the Martian arm of their nations are numerous; statesmen with a larger amount of military knowledge have much less often been in control of modern democratic nations in time of war. For this reason Jefferson Davis is of interest to the biographer.

His military opponent, General U. S. Grant, said late in life that Jefferson Davis fancied himself a military genius. Pollard and other historians writing in the 19th century, criticized Davis for a complete lack of military ability. The answer perhaps lies somewhere between.

Jefferson Davis through his three-fold career as soldier, politician, and statesman, found his martial spirit expressing itself in each phase. Some have suggested that less success in his Mexican War venture might have aided the Confederacy in its short life. True it is that his recognition for gallant conduct and strategical soundness in that conflict made him much more aware of his military abilities. It may be said that Jefferson Davis throughout his life was a political soldier, rather than a soldier politician. He approached political problems with military directness. He brought discipline to political life. Whether or not as a statesman he became lost in the details of military strategy, instead of setting forth a broad military policy, is a large question in this inquiry.

Jefferson Davis was born of Scotch-Irish stock in a four-room log cabin in Christian (now in part Todd) County, Kentucky, June 3, 1808. The fact that eight months later Abraham Lincoln was born in a log cabin some 60 to 100 miles away, has been a fruitful source of comparison for historians. The comparison has been drawn out to show how one man retained through life the homely common sense frontier-type personality, whereas the other developed a broad culture and was known as the typical Southern aristocrat. The Davis family emigrating to America in 1701 brought with it all the obstinacy and restlessness typical of the Scotch-Irish. They settled in Pennsylvania but the urge to move took them to Georgia, and before Jefferson Davis’s birth, to Kentucky.

Jefferson Davis’s father, Samuel Davis, prior to the war of 1812, tired of breeding blooded horses in the Blue Grass country and motivated by economic pressure, migrated to Bayou Teche in Louisiana, but the lowland heat caused another move to Wilkinson County, Mississippi. There the family settled down to the life of cotton farmers.

Life was simple on this cotton farm and the father, though possessed of little education, grew up with an inordinate interest in politics. Naturally, a man of his caliber would wish that his son be educated. After a short schooling in the log cabin near home, Samuel Davis decided that the youngest of his ten children should be sent to school in Kentucky despite Mrs. Davis’s objections. The boy’s name itself — Thomas Jefferson — indicated to some extent the hopes which his father had for his future.

Knowing the difficulties of travel to far-away Kentucky, through territory still peopled by Indians, Samuel Davis sought for a friend who would accept his son in a caravan going eastward. Major Hinds with his family being bound for Kentucky from New Orleans, took Jefferson Davis on this adventurous journey. The party mounted on horseback, stopped along the way at the little inns operated by white men who had intermarried with Indians, and at one stage in the journey visited at General Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage. They were well received, as Major Hinds had fought with Jackson only a few years before at the Battle of New Orleans. The elder Davis sons had also fought in the War of 1812, and Jackson therefore accepted young Jefferson with more than the usual courtesy. During their stay of three weeks, Jefferson Davis obtained an impression of the General which he expressed later in life: “He inspired reverence and affection which has remained with me through my whole life… my first vote was cast in favor of him for President.” The caravan, having resumed its march, left young Davis in Washington County, Kentucky, where he entered the school of Saint Thomas Aquinas, conducted by Dominican Fathers.

The tuition of $100 a year is said to have been paid by a Charles Greene of Bardstown, a man listed as Davis’s guardian. For two years young Jefferson, of a Quaker and Baptist back ground, lived in the atmosphere of Roman Catholicism. There he was taught Latin and from that study dated his liking for the sonorous phrases of his political speeches thirty years later. When nine years of age he returned home, to the great joy of his mother.

Jefferson Davis continued his studies in Adams County, Mississippi at what was called “Jefferson College.” From this school he was shortly transferred to Wilkinson Academy, near home. Resentful of the stern discipline which the principal, John A. Shaw, maintained, young Davis went to his father seeking sympathy. The father wisely said: “It is for you to elect whether you work with your head or hands. My son could not be an idler.” Accepting the side of labor, Jefferson was sent into the fields to pick cotton under the boiling Mississippi sun. Intellectual interests were in ascendancy by nightfall. At the Wilkinson Academy Davis averred that he learned more from the head master “than I ever learned from anyone else.”

In 1821 Davis returned to Kentucky to study at Transylvania University, “The Southern Harvard” in Lexington. Here he had the benefit of a liberal era in which that Presbyterian school came under the direction of a Yale graduate of Unitarian belief.

The studies at Transylvania were in the classical tradition and Davis was a diligent scholar of Greek and Latin and inherently loved political philosophy and history. J. W. Jones, a classmate who became a congressman and eventually one of Davis’s biographers, recalled Davis as “always gay and brimful of buoyant spirits… he never was perceptibly under the influence of liquor, and he never gambled.” By his senior year Davis “confesses to taking an honor” though he found need for a tutor in mathematics. At this time Samuel Davis died and Jefferson, the youngest child, came under the direction of his eldest brother Joseph, a prominent member of the Mississippi bar. At Joseph’s wish, Jefferson intended to finish the course at Transylvania and enter the University of Virginia, which was to be opened in 1825. For some unexplained reason Joseph Davis secured an appointment to West Point for Jefferson. Evidently the elder Davis had some connections in Congress, and had sufficient influence so that on March 11, 1824, John C. Calhoun, Secretary of War, sent his cadet warrant to President Monroe for his signature. As the warrant was posted to Transylvania, Davis did not receive it at Lexington until July 7. He immediately accepted the commission and briefly explained his tardiness. He stated that he would present himself at West Point before September and explain to the Superintendent upon his arrival.

At West Point the entrance examinations were successfully passed by Davis. There Davis lived a normal cadet life with its lack of recreation and its close attention to discipline and study. His scholarship was never brilliant and mathematics was again a most difficult subject for him to master. It is not surprising therefore that his final academic rating was 23 in a class of 33. Of lasting importance to Davis were the friendships he made in the Military Academy’s close-knit organization. His best friends were Albert Sidney Johnston, two classes senior, and Leonidas Polk, one class ahead of him. Two other men whom he saw much of later, Joseph E. Johnston and Robert E. Lee, were in the second class below him.

With his lack of distinction in academic and disciplinary lines, Davis was frugal to a point unknown by other cadets. Polk before him and Edgar Allan Poe after him, found the allotted $28.00 a month entirely inadequate to cover food and other necessaries. Despite the fact that Davis occasionally sent money to his mother he was yet able to partake of liquors at Benny Havens’s, the tavern famous in West Point history. Two serious mishaps arose from visits to Benny Havens’s. On one occasion Davis, in company with several other cadets, was caught and brought before a court-martial for drinking. The charges against Davis were of going beyond the limits prescribed for cadets, that he entered a public house, Benny Havens’s, where liquors were sold, and that he did drink spirituous and intoxicating liquors. Though four of the offenders were dismissed, Jefferson Davis was “pardoned and returned to duty” because of his past record of good conduct, and because of the skill with which he wrote his own defense. Davis argued that there had never been any official order forbidding cadets to frequent Benny Havens’s; also he claimed that the cider and porter enjoyed at the tavern were not spirituous liquors. Evidently the trial by court-martial did not deter Davis from repeating his visit to the congenial Benny Havens’s. While enjoying Benny’s porter, he was frightened by visiting authorities. Davis, in attempting to escape with a companion along the steep bluff of the Hudson River, fell forty feet and narrowly escaped fatal injury. From his own testimony his injuries were more than a serious shaking-up.

Other reminiscences of his West Point days recalled his meeting Joseph E. Johnston at old Fort Putnam to settle a dispute over some tavern keeper’s daughter. Johnston, the heavier but shorter cadet, is said to have given Davis the worst of the encounter of fisticuffs. If this is true it may be the basis for their difficulties during the Civil War.

Davis’s career at the Military Academy offers little to boast of and certainly no indication of his future ability was apparent. Other than a mediocre record in his studies and in “discipline,” or conduct, Davis carried with him a high sense of honor and duty, and a self-discipline which tightened his thin lips often during the remainder of his life.

Jefferson Davis in his autobiography modestly and briefly covers his active military career of seven years as a lieutenant in the army. “I graduated in 1828, and then, in accordance with the custom of cadets, entered active service with the rank of Lieutenant, serving as an officer of infantry on the northern frontier until 1833, when, a regiment of dragoons having been created, I was transferred to it. After a successful campaign against the Indians, I resigned from the army in 1835.” Evidently life on the frontier appealed to the adventurous young graduate at Davis’s time as it did to subsequent graduates throughout the remainder of the century. The United States had been at peace for some time prior to 1828 and the West offered the only real “soldiering.” His first army station, after graduation, was at Jefferson Barracks, in the gusty city of St. Louis. From that jumping-off place he next moved up the Mississippi River to Fort Crawford, now Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin.

Arriving at Fort Crawford on one of the triple-deck, stern wheel steamboats, Davis found himself at an extreme outpost on the frontier. For almost a hundred years a fur trading post sent out from Quebec had stood on the same spot. Near the Fort and up and down the river, were many Indian tribes, Sacs and Foxes, Wyandots, Menominees, Winnebagos, and Pottawatomies. On several occasions when Davis was out with detachments he and his men encountered warring parties. Davis spent his first spring in the army lumbering in the wilds of what is now northern Wisconsin. There on Yellow Creek a hundred miles from his home post he established a saw mill and set up Fort Winnebago. While there Davis was very ill at times and it was claimed that his faithful colored servant, James Pemberton, nursed him through these illnesses.

Life at Fort Crawford was similar to that of every other frontier fort. The army life reflected the life of the civilian population, and at this time was still agricultural. To obtain logs for the construction of forts, lumbering crews were sent into the woods. Davis was the leader of one of these crews and was therefore one of the originators of the lumber industry of Wisconsin, though for totally different reasons from those who followed. Returned from lumbering, there was always construction in progress. Others must work in the flour mills or engage in raising vegetables. Still others were sent out to drive cattle in for provisions. The army fort was the center of culture on the frontier, for its officers were the only men with college educations. Jefferson Davis with his desire for study entered into the life at Fort Crawford in all of its aspects.

Returning to Fort Crawford before winter set in in 1831, Davis had an opportunity to partake of the social life of this small post, and in the scouting and tactical problems about the Fort. Colonel Zachary Taylor, in the meantime, had taken command of the Fort. Jeff Davis and his fellow bachelors, all West Point graduates, began courting the three Taylor daughters.

Unfortunately for Davis, Colonel Taylor took a violent dislike to him. Various reasons are given for this aversion, one, that Taylor did not want any of his daughters to marry into the hardships of the army. Perhaps it is not unreasonable to see that a Post Commander in the wilderness, possessing as he did virtually dictatorial powers, could believe that he could make such an arbitrary dictum. For that matter, had this been the sole reason, the Colonel could have sent his daughter away. A more plausible answer to Taylor’s dislike of Davis is the squabble which arose between them, whether a newly arrived officer not in uniform would be allowed to sit on a court-martial. On this occasion Taylor is said to have refused to accept the newly arrived officer’s excuse that his uniforms were in his trunk then en route to the Fort. When the matter was brought to vote among the court-martial’s officers, Davis sided with others to continue the trial. This event seemed to cloud Taylor’s appraisal of Davis’s good qualities. At any rate he was refused access to the Taylor household.

The Black Hawk War broke out in the upper Mississippi Valley in 1832, Fort Crawford being within the battleground. The Indians, notably the Sacs, were angered because they were being pushed off the rich land east of the Mississippi. Though Black Hawk had signed away the legal right in a treaty, he reasoned that the land could not be sold. He stated: “The Great Spirit gave it to his children to live upon…” The Federal Government had weakened its position following a full treaty payment of $1000 by a shamefaced peace token of 60,000 bushels of corn. Numerous young graduates of the Military Academy were present in the theater of war. Albert Sidney Johnston, Davis’s friend, was one of these; Robert Anderson, later the Union hero at Fort Sumter, another. Fighting with these young officers were many militia officers like Abraham Lincoln, who was said to have been sworn in as a Captain of Illinois volunteers by Lieutenant Jefferson Davis. The militia had been called out for a period of thirty days to fight the Indians, and Lincoln flippantly remarked: “I had a good many bloody struggles with the mosquitoes…”

The military operations were engagements between small detachments, and the final battle of Bad Axe was fought twenty miles up-river from Fort Crawford. Though Black Hawk escaped, leaving 190 warriors dead or captured, he was closely pursued by Lieutenant Davis’s detachment. Davis’s report of the capture of the Indian Chief gave credit to aid from the Winnebagos. Robert Anderson was ordered to take Black Hawk and the other Indian prisoners to jail, but his illness gave Davis the assignment. The group moved down-river on a steamer to Jefferson Barracks. Black Hawk said of Jefferson Davis that he was a “young war chief who treated us all with much kindness.” Though Davis returned shortly afterwards from this duty to Fort Crawford he had only a brief period to whisper a few words to his lady-love, Sarah Knox Taylor. Whether or not they became engaged at this time is rather doubtful. Davis’s next move was to Fort Gibson, in the spring of 1833, where he joined the new regiment of cavalry, the First Dragoons. His reasons for this action were his undoubted love for horses and perhaps his wish to be removed from Colonel Taylor’s ire. Fort Gibson of the 1830’s was described by Bonneville, and by Washington Irving, who visited it at that time. For the next two years Davis remained at Fort Gibson. He corresponded with “Knox,” as Taylor’s daughter was called and perhaps saw her more than once during this period. Eventually Davis announced to the irreconcilable parent that marriage with his eldest daughter would take place in the near future.

Jefferson Davis, as Adjutant of the First Dragoons, was sent off from Fort Gibson to “impress the wild Indians” with the might of the United States. Several of these expeditions, notably that of Toyash, took the dragoons into the Comanche country, where their display of force brought the Indians to the peace table. Returned from this difficult journey with an appalling amount of sickness which accounted for 163 members of the Dragoons in slightly more than a year, the regiment’s morale was not of the best.

Major R. B. Mason appointed Davis his acting assistant quartermaster late in 1834. “Somewhat of a martinet,” according to Grant Foreman, Major Mason upbraided Davis for his absence from a reveille roll call. For speaking in a disrespectful and insubordinate manner, the young Lieutenant was placed in arrest in quarters. Because of Davis’s failure to move at once to his quarters, the order was repeated a second and a third time. Only at the last peremptory command did Davis obey. At a court-martial held at Fort Gibson, February 12, 1835, the acquittal stated that: “No criminality (was attached) to the facts of which he is found guilty.” Several weeks later he asked for leave of absence. When this was granted, Davis before departing left his resignation in the hands of General Arbuckle, asking that it be forwarded to the War Department if he did not return at the specified time. General Arbuckle held up the resignation as long as possible, hoping that Lieutenant Davis could be induced to return. Davis had gone to Kentucky to be married. He never returned.

Other than the court-martial, many reasons for Davis’s resignation can be assigned. America was opening up and the opportunities for amassing wealth were much increased; this, coupled with the slow promotion in the army, as evidenced by the fact that Robert Anderson, a graduate of 1825, had only reached a Major’s commission when in command at Fort Sumter in 1861, was reason enough for the many resignations during the 1830’s. An objective critic would say that these men showed a certain wisdom, even though a lack of loyalty. A large number of West Point graduates entered civil pursuits and had reached some eminence when called into the army for the Civil War. Due to the systems of promotions through the militia and by political appointments, there was no deterrent to their reaching high rank as quickly as their brother officers who had remained in the army. Jefferson Davis probably desired the quieter life of a planter because of the influence of his older brother Joseph, who seemed willing to share some of his considerable fortune with his youngest brother and protege. Within a month after his resignation, Davis was meeting his fiancee. The marriage of Sarah Knox Taylor and Jefferson Davis has often been called an “elopement,” but the facts do not support this contention. Mrs. Gibson Taylor, Knox’s aunt, pleaded with Colonel Taylor to change his mind about Davis; and he finally gave his reluctant consent. The marriage was performed at Mrs. Gibson Taylor’s home in Kentucky. Knox wrote to her mother of her marriage plans. Mrs. Taylor was only surprised by its imminence. The daughter assured herself in this letter that her mother would still feel affection for her daughter who was being married without the sanction of her parents. The bridal couple settled down on a portion of Joseph Davis’ plantation, calling their home “Brierfield.” This plantation, which lay in a bend of the Mississippi River some 20 miles below Vicksburg, was an isolated home in a not-too-healthy climate. In a short time Mrs. Davis contracted the dread fever and in less than three months after her marriage was dead.

Jefferson Davis, following his wife’s death, moved up to his brother’s plantation home and there lived for years the life of a hermit, acting as an absentee landlord of his own “Brierfield.” During this period Davis by study and reading and discussion with his brother Joseph, a Jeffersonian Democrat, supplemented his collegiate work with a good insight into political problems. In time Davis too became a Democrat and a firm believer in strict construction of the Constitution. From his plantation management he derived two convictions: “That emancipation will not solve the negro problem; and that the only hope for improvement in the negroes’ condition was in the slow process of fitting him for economic competition with his white superiors.”

Davis in addition to his inherited attitude toward slavery, also acquired the “Southern Gentleman’s Code.” In the latter, gambling debts were most sacred and dueling was the only proper method of dealing with an insult. During this period of seclusion and study Davis had an unparalleled opportunity for discussion and for the acquisition of certain political theories, all of them colored by his environment. In 1843 Jefferson Davis entered practical politics with his educated background and his cosmopolitanism aiding him in quickly reaching the higher rungs of the political ladder. From Davis’s nomination to the Mississippi State Legislature by the Democratic Party he was a man of the people and continued to belong to the public until his capture in 1865.

Davis’s entry into political life came about in this way. The Whigs, who usually commanded a majority in Warren County, Mississippi, put up two candidates for the seat in the Mississippi legislature. The Democrats, hoping to win by a split vote, put up a candidate who proved unsatisfactory. The nomination of Davis as a substitute a week before the election brought forceful opposition from the Whig party. Sergeant S. Prentiss, a famous New Orleans orator, met Davis in debate. Though Davis, in this first political speech, was inept compared to Prentiss, his character so impressed itself upon the electorate that he was defeated by far fewer votes than any previous Democratic candidate. Because of his good work Davis was next named a delegate to the Democratic State Convention to select a Presidential candidate. At the Convention Davis made a strong speech for John C. Calhoun, the former Secretary of War, who had appointed him to West Point. In the fall of the year Jefferson Davis was named an elector on the Polk-Dallas ticket. The young politician was now launched on his career.

Good fortune came to Davis in 1845, for he married a very capable woman, Varina Howell, and was also elected to Congress from the state-at-large. The Howell family had moved from New Jersey to the Mississippi River country where Howell became a leading citizen and lawyer of Natchez. William Howell and Joseph Davis were close friends, so that it was quite natural for Varina, his daughter, to visit the Davis plantation. She was at this time 17 years old with dark eyes and hair and a certain haughtiness. Jefferson Davis on his journey to Vicksburg to make a political speech stopped at a niece’s plantation where Varina Howell was staying to tell her that she was expected at his brother’s plantation home. Varina wrote to her mother a significant letter: “Today Uncle Joe sent, by his younger brother (did you know he had one?), and urged an invitation to me to go at once to ‘The Hurricane.’ I do not know whether this Mr. Jefferson Davis is young or old. He looks both at times; but I believe he is old, for from what I hear he is only two years younger than you are. He impresses me as a remarkable kind of man, but of uncertain temper, and has a way of taking for granted that everybody agrees with him when he expresses an opinion, which offends me; yet he is most agreeable and has a particularly sweet voice and a winning manner of asserting himself… I do not think I shall ever like him as I do his brother Joe. Would you believe it, he is refined and cultivated, and yet he is a Democrat!” Before Varina Howell left the Davis home she was engaged to the man whose character sketch she had done so perfectly from first sight. They were married February 26, 1845, at her father’s home. The wedding trip was a prosaic steamboat journey to New Orleans. Davis’s campaign for Congress was not as smooth as his courtship.

During the campaign the question came up of the payment of bonds, which had previously been issued by the State for the stock of certain banks. The leader of the Democratic party, one Briscoe, another Democrat, was for the repudiation of these debts. Davis took the opposite, and unpopular, stand against repudiation. He stuck to his guns, bearded Briscoe, caused pamphlets to be published, and in a bitter fight won the Congressional nomination and the election. It is unnecessary to note that even Briscoe voted for Davis in the end. Long years later this old controversy was brought up when the Confederate States requested a loan of England. No matter ever wounded Davis more than such reference to his early stand against repudiation of the State’s debt, for Davis felt that his honor was involved in the case. Before leaving for Washington, Davis had occasion as representative-elect to present John C. Calhoun to a group of Democrats at Vicksburg where the great statesman had stopped on his way to a Convention at Cincinnati. Carefully Davis wrote out his address and presented his views upon certain political issues of the day; low tariff, sound currency, the annexation of Texas, and a strict construction of the Constitution. Sagely the young politician left the doctrine of nullification to Calhoun, knowing well that it was the visitor’s favorite topic. Davis’s speech was well received and finding that he had spoken extemporaneously, with his written speech only a guide, stated that it would be the last speech he would put into manuscript. Even Calhoun was able to recall the incident five years later and predicted that his successor “as leader of the south would be the young scholar-planter, Jefferson Davis.”

Jefferson Davis, now 37 years of age, took his place in Congress in December 1845. Gamaliel Bradford said that Davis almost at the beginning of his career in the Federal Government was known as “a scholar and a thinker.” Such men were needed in the controversial state in which the nation was living, according to Robert McElroy. He said further that Davis’s personality and gift for leadership accounted for his rapid progress in politics, though one must not forget that he had studied much and had knowledge and conviction “upon the two great issues of the day; the rights of slavery and the rights of sovereign states.” True enough Davis appeared a little cold and perhaps too dignified when he presented his legalistic points of view but he had so many advantages for the career of a politician that it was not surprising that he rose to fame. Varina Davis said of her husband’s congressional life that he visited very little and studied until two or three o’clock in the morning. His visitors were few in number, though Calhoun was an accepted friend and many of Davis’s former comrades in the army stopped in to see him on their visits to Washington. Within a few months Davis was entering into the discussion on the floor of the House.

In May of 1846 Zachary Taylor, who had led his army into Texas to guard the boundaries, collided with Mexican soldiers and awoke the country to Mexican difficulties. Davis took the floor in Congress a few days later to support a resolution of thanks to General Taylor for his frontier guard. He went on to praise the American army officers and emphasized that “it was the triumph of American courage, professional skill, and that patriotic pride which blooms in the breast of every educated soldier.” Then turning to a fellow Congressman, who had denounced West Point and its graduates, he unfortunately blundered into asking this man, Andrew Johnson, if he believed “a tailor could have secured the same result.” Johnson’s temper, for which he was notorious, rose in response to what he believed an insult to his former calling. The next day Johnson responded in resentful tone to the “illegitimate, swaggering, bastard, scrub aristocracy,” in which he placed Davis as a member. The austere Jefferson Davis at once made known that there was no thought of personalities in his remark. Two days later, while discussing an army pay bill, he said once again that he was incapable of wounding the feelings of any man knowingly. Davis’s Congressional career came to a temporary end in June of 1846 when Mississippi called him to lead its Mexican War volunteer regiment. Jefferson Davis, like Teddy Roosevelt later, began preparations for war by selecting the best available arm for his men. He made himself unpopular with the veteran army chief, General Winfield Scott, by passing over his objections to the Whitney percussion rifle and ordering sufficient for his regiment. With this, the best arm of its day, on their shoulders, instead of the old flintlock muskets, the regiment assembled at a New Orleans camp where they were met by their Colonel. Very soon the “Mississippi Rifles” had moved to Point Isabel on the Texas coast where Davis began drilling his men and implanting in them the discipline which ruled his own life. In his camp on Brazos Island, Colonel Davis heard from his old commanding officer, Zachary Taylor. General Taylor said that he took much pleasure in the fact that Davis had safely arrived with an excellent regiment of volunteers. “Old Rough and Ready” said further, “I can assure you I am more than anxious to take you by the hand.” Evidently time had healed animosities and Taylor was pleased at having in command of a volunteer regiment an ex-congressman who could speak capably and sincerely in favor of the army, and more particularly of General Taylor. After some drilling the Mississippi Rifles were transferred to the mouth of the Rio Grande, where they awaited the overdue transports.