Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 9 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 8: Death-Dance in Pastrana)

________________________________________________________________________

“RESISTANCE ON LEYTE VANISHING.”

(Newspaper headline, Oct. 30, 1944)

________________________________________________________________________

On a Sunday morning advance patrols peered into the out skirts of Jaro. They saw forty Japanese engaged in taking a field bath in the manner approved by Nippon’s Imperial Army.

The Japs had cut the tops out of two empty gasoline drums. They were filling the drums with water. Under one they then built a fire kindled with planking torn from a peasant’s hut. Next to the drums they placed a wooden grating to prevent their feet from becoming muddy. When the water in the first drum was hot enough, the highest ranking officer was called. All others lined up behind him, naked, and according to rank. The senior officer took his bath first. The others followed, one by one. They soaped themselves in the first drum, and rinsed in the second. The one-star privates bathed last. After the bath they lined up, faced in the direction of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, and bowed. The hidden watchers of this scene could not suppress their laughter. Dogs began to bark, and the patrol was forced to fade into the brush.

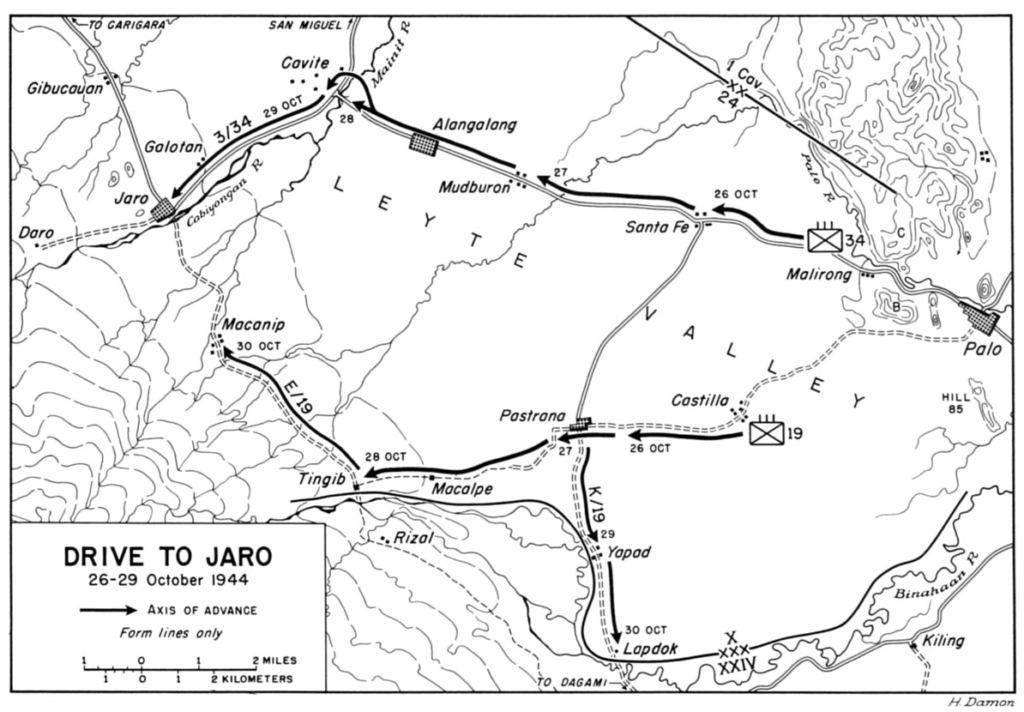

But these Japs, and many others like them, fought hard for Jaro. The town of Jaro, at the foot of twin-peaked Mt. Mamban and on the upper reaches of the Mainit River, is the key town of the Leyte Valley. Here the highways from Palo, Dagami and San Miguel meet and turn north to Carigara and the sea. The battle for the country around Jaro will never be forgotten by Colonel “Red” Newman, nor by any man of his command.

The thick-set, red-haired colonel folded up his map. He put away pencil and notebook. He checked his pistol and his carbine and he tightened the strap of his helmet across his chin. No one had ever seen Colonel Newman send a soldier to confront a hazard which he was not quietly willing to share. No one had ever seen “Red” Newman wavering or undecided. His movements were deliberate and sure. Aged forty-two, an infantryman to the core, the colonel was a fine combination of leader, athlete and man of letters. At West Point he had set a record by running a mile in four minutes and twenty-three seconds. In 1928 he had gone to Amsterdam with the Olympic team. He had also written and published more than a million words; but not even his friends knew his nom de plume. They teased him that morning when they saw him scribble in his notebook. “A man’s hobby is his private affair,” he smiled. “Gentlemen, prepare for the scrap.”

The Third Battalion led the regiment’s march on Jaro. Its vanguard was “Love” Company, and the vanguard’s commander, Captain Richard J. Baker of Baltimore was rated one of the coolest combat officers in the Division. The force pushed up stream along the Mainit River, past washouts and blasted bridges, and flushing snipers out of trees on the way. A soldier left to guard a bridge was rushed by a lone Japanese armed with a club; he shot his assailant fifteen times before the Jap lay still. Little happened until the battalion point approached the village of Galotan on the outskirts of Jaro. There the lead scout saw a bare-legged man scurry into a hut. He thought the other was a Filipino, and shouted for the man to come out. The answer was a bullet between the eyes. The scout’s comrades raged forward. They broke down the hut and fairly tore the bare-legged enemy to shreds. Murderous fire lancing from a scattering of shacks drove the squad to cover. Another American was killed and several were wounded. The Japanese were solidly dug into the mud and excrements beneath the native houses and they intended to stay there. They had to be rooted out and killed one after an other, and it was a slow and bloody task.

A young Californian, Private Lester Wyckoff, from Tehachapi, did not know that the scout was dead. He summoned a corpsman and together the two carried the fallen scout to a safer place. Only then did they see that they had rescued a dead man. Young Wyckoff, in towering anger, grabbed his Browning automatic rifle and rushed forward again, firing to avenge his comrade.

Forward with him went the squad’s second scout, another Californian, Corporal Raymond Andrus from South Gate. They plunged into a short-range exchange of fire with the Japs under the shacks, and Andrus was shot through the wrist. He ran back to the aid man and said, “Hey, Mac, bind me up.”

He was given first aid and Captain Baker ordered him to the rear as a walking casualty. Corporal Andrus protested. “All right,” grinned Captain Baker, “get forward then, and fight.” And fight he did until the last Jap under the huts of Galotan was ready to be buried in his own hole.

Slowly “Love” Company’s men forced an entry into Galotan. A radio operator, John Goodley of Wilmington, Delaware, lay behind a smashed well. He was waiting for messages to be transmitted to the battalion commander. But Captain Baker was too busy to think of messages just then; so Operator Goodley put his radio aside, snatched a dead man’s rifle, and joined in the assault. Whenever he saw a Jap helmet appear in the murk be neath the shacks, Goodley paused, took careful aim and squeezed the trigger. He seemed oblivious of hostile bullets which kicked sprays of mud into his face. He fired until his ammunition was used up. Then, at a bear-crawl, he moved about, looking for more ammunition. Instead he came upon a wounded comrade. The wounded soldier was so badly hit that he could not be moved except on a litter. The radioman ran to the rear. He called a corpsman and guided him to the spot where the wounded man lay. On the way he picked up another clip of ammunition. While the medic worked to stop the flow of blood, Goodley stayed with him and shot away at three Japs who had made up their minds to kill the exposed group. Captain Baker saw his aide fall wounded at his side. Another officer, Lieutenant John B. Clark of Santa Barbara, California, was wounded but continued to lead his men in the attack. But

Captain Baker signaled a halt. He called for artillery fire. In not many minutes the Division’s omnipresent cannoneers sent shells roaring among the shacks of Galotan. Geysers of mud, debris and enemy bodies danced under the palm fronds. The air was rent by the concussions and the earth trembled. The artillery barrage was soon stopped; infantry lay too close to the impact zone of the shells, and the dogfaces were as loath to give up their hold on Galotan as were the Japanese.

Captain Baker maneuvered platoons around both enemy flanks. “Love” Company resumed the assault. The ordeal lasted two hours. Wounded squirming in the killing zone were hit again and again. The sight of bullets slamming into the bodies of friends already down and out made the still fit go on a rampage. The Jap war left no room for mercy. You see an enemy who blinks his eyes or still kicks feebly and you bash in his skull as you run by. He may be only a poor peasant’s son who did not want war. But in combat he becomes a viper whose last convulsion may roll a lethal sting your way.

Private Edward Klehamer of Runnemede, New Jersey, a surgical technician, was in the front line. He was unarmed as most medics are. He saw a soldier crumple and he lunged forward to the wounded fellow’s side. He began to drag him to the rear, ducking low under the zipping of lead. Then bullets struck the ground between his legs. The aid man went unscathed, but the wounded man was killed. Klehamer sat hunched over the corpse. He shook his fist at the Japanese under the huts of Galotan. The Japs fired again. Klehamer did not budge. It took an officer’s sharp command to make the medic abandon his attempt to drag the dead buddy out of the sights of enemy guns.

An hour later, in the same fight, the officer buckled under a crackling of Jap rifles. He fell thirty yards in front of the most advanced American squad. Klehamer dashed forward to the officer’s side. The firing mounted in intensity and Klehamer was unable to move. But he remained with the wounded man and tended his wounds until relief arrived. The aid man’s awesome duty of facing death without the bleak privilege of dealing death had not shaken the corpsman from New Jersey. After a minute’s rest and a draught of chlorinated water he said simply, “Let me go. I want to help.”

The squads advancing along a river bed to flank the Japanese strongpoints were nailed down by sheets of gunfire. The riflemen sought what cover they could find. The answering fire of the Garands waxed to a staccato roar. Sergeant James Mclntyre of Barlow, Kentucky, had crawled out to drag a badly hit man of his squad to a hollow in the ground. When he returned he found that his men were burning up their last clips of ammunition. The situation threatened to become a matter of rifle butts against automatic weapons.

As if by miracle, succor came. Some distance away a squad commanded by Sergeant Paul R. Willis of Dallas, North Carolina, lay in a fire fight. Firing, at this point, was sporadic. Sergeant Willis heard the tempest rage down by the river. His battle-wise ears enabled him to distinguish between the solid barks of the Garands and the whip-like cracking of Japanese weapons. He became aware that the volume of barks diminished while the flat cracking increased. “Guys over there are getting short of rounds,” he said.

He acted promptly. Bent low, he raced from man to man along his skirmish line, collecting surplus ammunition. Enemy snipers in a nearby pig-pen fired at the running American. Presently Sergeant Willis was loaded heavily with bandoleers. He dashed across the highway, across a patch of rice field bordering the river. He brought the ammunition to the beleaguered squads. The men were grim, grateful.

After that, “Love” Company closed in for the kill. Under the mud-bound shacks of Galotan scores of Japanese died horribly.

While fighting raged in Galotan, Lieutenant Colonel Postlethwait, commanding the regiment’s Third Battalion, dispatched several companies on a wide arc to envelope Jaro from the north. This force was halted by machine guns firing from tunnel emplacements on a wooded knoll. Postlethwait radioed for artillery fire. Soon the shells came screaming in over the heads of the pinned-down flanking force. The defenders abandoned the knoll. A patrol went forward through steep thickets. It found fifteen Japs chewed to pieces by bursting shells. The bulk of Japanese then retreated into the hills to the west. But they found the ridges occupied by Nineteenth Infantry detachments which had speared north from Pastrana. The cornered enemy sought cover in the river bed, set up machine guns and fought fiercely. He was supported by artillery pounding from yet undiscovered roosts beyond Jaro.

Out of their trap Nippon’s fighting men counterattacked with fixed bayonets. On the extreme right flank of his company lay Private George Ferries of Bakersfield, California. Smoke from exploding Japanese shells obscured his vision to the front. He held his head low to the ground, his helmet turned toward the explosions and his face held sideways. What he saw off to his flank made him sit up and shout an alarm. Swarms of Japs came in a counter thrust around the shoulder of a low hill on the company’s right. The riflemen met the onset, threw it back.

At this time a West Virginian, Corporal Robert L. Church, a medic, was on his way to the rear suffering from fever and battle exhaustion. He heard the noise of fighting and asked, “What’s going on?” A lineman who was trying to string wire across a clump of splintered palms told him. “Plenty” the lineman said.— “Any wounded up front?”— “Quite a few,” the lineman said. Shivering, barely able to stay on his feet, Church turned and gathered a litter squad. Five times he led his squad of aid men to the front to bring the wounded to safety. He did not quit until he had helped to give first aid to forty wounded soldiers in less than an hour’s time. He then escorted his patients to the immediate rear where the battalion surgeon, Captain Donald B. Cameron, took over.

Men are transformed in battle. They stand alone and naked for everyone to see. The Yokohama coolie may be a docile fellow at home, but he becomes a beast of prey when he suddenly confronts you with a grenade in each hand. Someone you relied on suddenly cringes with fear. Other men whose existence you barely noticed through months and years abruptly loom before your eyes as giants of courage and of willingness to help. Private James Robinson who is married to a girl in Pauli Pike, Indiana, crawled four hundred yards through Japanese mortar and machine gun blasts to lug badly needed mortar ammunition to his outflanked squad. No one who has never carried mortar shells in tropical heat can know what that means. It means pain, crucifying pain…. A mortar shell made in Nippon burst and critically wounded three men. They struggled in a puddle of mud and blood and they shouted for help. Technician Clarence Temple of Sheridan, Wyoming, crawled forward and helped them while other mortar shells made in Nippon exploded far and near…. Private Howard F. Day whose wife lives in Freeport, Illinois, carried a load of mortar shells through thicket and swamp. And after delivering his shells he crawled off to the right where two enemies were sniping and killed them both…. Sergeants Andrew Koassechony of Apache, Oklahoma, and Bernard Mills of Brooklyn, risked death to save a soldier who had fallen on patrol. A Japanese machine gun hammered twenty yards away. When they reached their comrade they found that he was dead. Sergeants Mills and Koassechony brought back only the dead man’s rifle and the letters and a photograph they had found in his pockets. “We thought his mother might want them,” they said.

In battle men can hide nothing. There was an officer who threw himself into a ditch and wept. There was a sergeant who threw away his rifle and hid his face in his hands. A boy of nineteen went insane from fear. But there was also Sergeant James Cimmiyotti from Kimberley, Oregon, who went into a swamp and killed a sniper who had shot a man in Cimmiyotti’s platoon. And there were the two “Able” Company sergeants who with their bodies protected armored self-propelled guns.

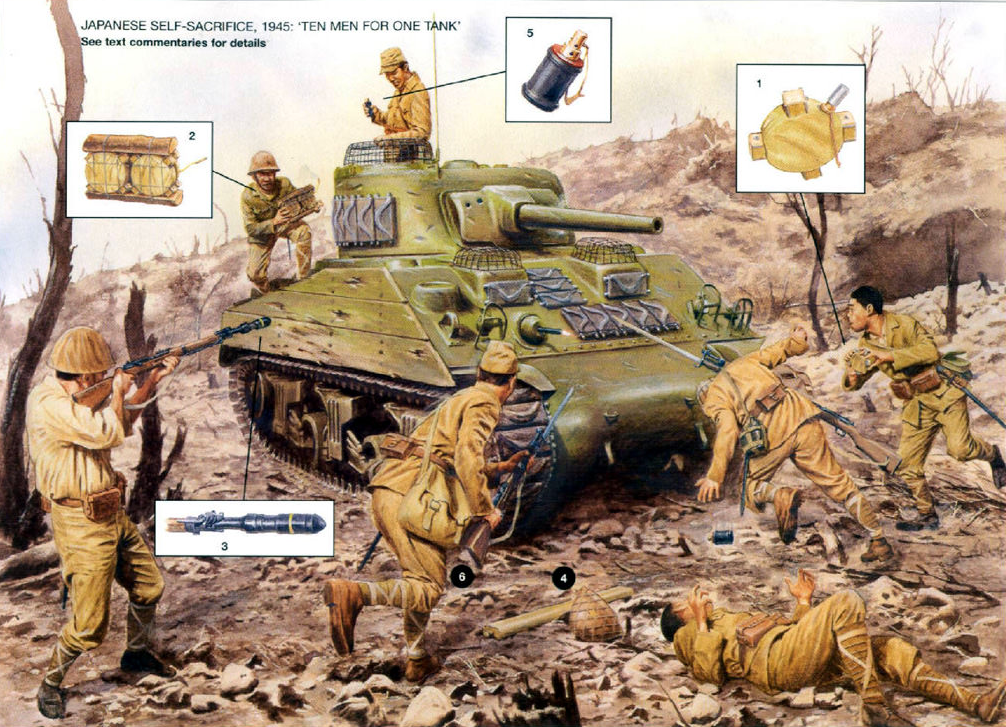

Colonel Newman had sent tank destroyers forward to deal with Japanese strongpoints at point blank range. Now, tanks and anti-tank guns were fine weapons. But on rough, overgrown ground they are vulnerable to attack by small suicide units. Tanks must move slowly along jungle-flanked roads where the terrain is treacherous and vision is bad. Japanese anti-tank assault teams were trained to strike tanks at their vulnerable points: treads, rear, observation ports and periscopes. One man uses a long pole to place a mine under a moving tread. Simultaneously another man may throw a “Molotov cocktail,” a bottle filled with a mixture of oil and gasoline. This mixture set afire transforms the tank into a broiler for its occupants. At the same time other men will mount the tank and use grenades and rifles against the ports. Jap tank-hunters used smoke grenades and smoke candles to blind the crew. Or they tried to halt the tank by jamming a log between the driving wheels. Or a Jap would strap a mine to his belly and then throw himself in front of the crunching tracks. Tanks needed infantry protection to guard them against such suicidal charges. Sergeants Robert Bowman of Newburyport, Massachusetts, and Louis H. Hansel of Mount Vernon, Kentucky, were ordered to guard the steel flanks of self- propelled howitzers going into battle.

The infantry withdrew. The two noncoms led their platoon forward. As the tank-destroyers closed with the enemy nests, Bowman and Hansel drew their protecting ring of riflemen about the lumbering giants. They warded off two assaults by demolition units as the SPM’s completed their mission. Then the tracked guns turned and headed rearward. Withdrawing, Sergeants Bowman and Hansel found two badly wounded sol diers. They signaled the SPM’s[1] to halt. Under aimed fire they stood upright to load the wounded aboard the tracked mounts. After that they saw them safely to cover. Sergeant Bowman was painfully wounded. Louis Hansel died in action.

At 5 p.m. October 29, the storm elements of the Thirty-Fourth entered Jaro. Carigara lay ten miles to the north. On that day thirteen Japanese transport ships carrying reinforcements to Leyte were bombed to the bottom of Camotes Sea. Seventy-six raiding Japanese planes had been shot down. The news was good. That evening an Associated Press correspondent echoing MacArthur’s optimism, cabled home that “all organized Japanese resistance appears to have ceased in the strategically vital Leyte Valley.” This newsman did not see the rows of cold, stiff figures on trucks rumbling to makeshift cemeteries among the swamps.

That evening Jap ammunition depots in Jaro were set ablaze by unknown hands. “Love” Company was again the vanguard of a battalion pushing north from Jaro an hour before dusk. A field report states that, “The leading platoon came under heavy fire and several men were hit. Captain Baker immediately moved forward in the face of enemy fire and supervised the withdrawal of the platoon from an untenable position, and the evacuation of the wounded…. Later the same day, after Company “K” had been pinned down by machine gun fire from its left flank, Company “L” was ordered to make an enveloping movement to the left. The company moved into position and attacked through a palm grove. The enemy initially held his fire and then, from well camouflaged positions on commanding ground, opened fire with five or more machine guns and thirty or more rifles. Many of our men were killed or wounded in the first minute….”

The men of the Thirty-Fourth dug in for another night. Through the darkness artillery thundered. Captain Baker was thirsty after this day of sweat, death and filth. He reached for his canteen. The canteen was empty. A Japanese bullet had pierced it.

From midnight to dawn rifle and machine gun fire rippled. Jap infiltration parties were on the crawl. From midnight to dawn rain fell steadily upon the tired men.

In the pre-dawn darkness of October 30 Colonel Newman threw off the poncho under which he had rested. He arose, muddy, wet, but with confidence that the day would bring the decision of the battle for Leyte Valley — the break-through to the sea. His regiment’s planners had worked all night in little blackout tents hidden behind jungle barricades. In the rear the engineers had toiled to make the roads fit to bear the traffic of ammunition and supplies. Between the Mainit River Bridge and Jaro two major washouts had blocked the road. The engineers had built a by-pass around one; they had brought bulldozers and they had changed the course of the river to make passable the other. The Division Command Post moved forward, hard in the wake of the fighting troops.[2]

The task of finding sites for the forward displacement of the Division Command post fell to Lieutenant Colonel Thomas H. Compere, a Chicago lawyer whose chief ambition it was to go back to the practice of law. On his reconnaissances far in advance of the staff he often came under hostile mortar and machine gun fire, and more than once he was a target for snipers lurking in head-high grass. A division command post in the field is a complex thing — a moving city of drab little tents, of jungle hammocks, field desks, radios, trucks and jeeps. Its numerous “sections” range from “Operations,” “Artillery” and “Intelligence” through “Counter Intelligence,” “Ordnance,” radio, message and medical centers — to mention but a few — to the officer whose duty it is to serve the melancholy needs of the dead. The location of camp sites for the Division’s brain, near enough to the front and on ground allowing for effective defense against night raids, was no easy job. On invasion day the craft carrying Compere’s party was struck by shells and an aide was killed and fifteen others wounded. On Red Beach the mild-mannered lawyer had calmly gathered the fit and set out to find America’s first command post in the Philippines. On another day he picked a spot so far advanced that an enemy counter-attack threatened to overrun it. Artillery fire fell among the men who laid out the camp, striking down eight. But already Tom Compere was preparing to push Headquarters into the town of Jaro.

“All right,” said “Red” Newman, “we’d better slug on, then.”

The road from Jaro to Carigara crosses twelve streams which flow from the gorges of the Mt. Mamban massif. Before the regiment reached Carigara, all twelve bridges had been burned or blown to wreckage. The road was blasted and mined, and the thickets and plantations along it were charred by an eighteen-hour artillery barrage. Every weapon that the Division’s field artillery battalions could muster belched steel and high explosive.

The infantry attack jumped off at 8 a.m. The men who pulled northward out of Jaro that sultry morning felt they were giving their last. They cursed the existence of Carigara and they cursed the road and its vile flanking terrain. Again “Love” Company was in the vanguard. Machine gun fire flashed where the road leaves Jaro toward the village of Tunga. As on the previous day, the hurricane of bullets sprang from deep emplacements hidden under native houses. As on the previous day, men fell in bitter huddles. Again there were the groans, the blood, the wordless savagery, and corpsmen hastening to aid the fallen. Under direct fire the leading elements fell back.

Sergeant James Walker of Bowling Green, Missouri, and his section of machine gunners covered the withdrawal. They set up their guns and poured lead into the Japanese under the shacks. Four times during this duel of the machine guns Walker left cover and stood up to direct and control the fire of his gunners.

On the left flank of the stalled assault a platoon was nailed to the ground by two Japanese machine guns. Their firing came in vicious relays. Boldly three members of another American machine gun crew met the crisis. To save the platoon they sacrificed whatever shred of safety there was in lying flat. In full view of enemy gunners they mounted their weapon. Again it was machine gun against machine gun.

A mortarman who observed his comrades’ plight advanced in leaps and bounds. He reached a position on a grassy bank from which he was able to get a clear view of the Japanese strongpoints. There he knelt, directing with signals of arm and hand the fire of friendly mortars emplaced in the rear. Soon mortar shells dropped on the Japs. But the enemy had spotted the observer. The guns spat and the observer died. His name was Bruno Krasowski, of Lodi, New Jersey.

Now Japanese artillery fire found the American ranks. Shells from anti-tank guns, from anti-aircraft cannon, and from heavier field pieces plowed the highway between Jaro and Tunga. Private Enos Torsch from Lachine, Michigan, located a Japanese cannon whose shells were preventing withdrawal of the forward platoons. To another soldier he called, “Come on, let’s knock that baby out.”

The two volunteers proceeded to a grassy knoll and brought their Garands to bear. The Jap cannoneers dived into a ditch. Pursued by the rattle of hostile automatic rifles Torsch and his buddy dodged back to cover. On the way they found a wounded comrade and took him along.

Sergeants Modester Duncan and Ralph E. Trank halted in the withdrawal because they saw that another of the wounded men had been left behind. The wounded soldier was flopping about in the road. He was trying to drag himself to shelter. Said Trank, “Can’t leave that Joe there to die.” Duncan agreed. Together they ran into the firing zone and carried the injured man to the rear. Duncan hails from Mooresbridge, Alabama; Trank’s home town is unknown.

Unaware of the retreat was Private Wilber Spoonhour of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Spoonhour was a scout. When enemy fire became thick and deadly, he was out in front of his team. He did not know that the men behind him had been ordered to withdraw. His stomach tight, he continued to advance — alone. He penetrated the Japs’ line of defense. And suddenly he realized that he was isolated and surrounded by the foe. Spoonhour was scared, but he looked around. He saw exactly how and where the Japanese defenders were deployed. Then he retraced his course. On chin and toes he crept from shack to bush, from bush to ditch, from ditch to palm, from palm to mudhole, and then he suddenly stood up and shot his way back to friendly lines. The information he brought back about enemy positions saved many American lives.

Halfway in tortured no-man’s-land a lone soldier lay behind a stump. The soldier was firing his Garand steadily at the slope of a brush-covered knoll which flanked the road. Japanese snipers, in turn, were firing at the man behind the stump. “What’s Andy firing at?” his comrades wondered. And then they saw. With a solid disregard for the snipers the soldier was shooting at Jap machine gunners who tried to prevent a group of corpsmen from bringing in the wounded. The lone rifleman was Andrew Zubal, Private, of Watervliet, New York.

Between Jaro and Tunga the medics were at their best. First aid stations which accompanied the advance were swamped with wounded: men ripped by bullets, men mangled by grenades, men with broken bones and biting burns, men knocked unconscious by concussions and men whose legs had been torn away by bursting shells. Captain Donald B. Cameron, Battalion Surgeon, of Calhoun, Kentucky, moved emergency stations to within thirty yards of the firing lines. He so cut short the time which would have been consumed in carrying injured soldiers farther to the rear.

Sergeant Carlton Grode of Menasha, Wisconsin, and his litter squad crawled two hundred yards through machine gun and mortar strikes to aid the critically wounded. Staff Sergeant Chester Jordon of New York Mills, New York, and his corpsmen went forward five times into no-man’s-land to evacuate the fallen. Private Norval Hill from Summerfield, Ohio, advanced one hundred and fifty yards into all hell to tie a splint to a comrade’s broken leg; so did Aid Man Francis T. Hall of Centralia, Illinois, and others whose names no history book will mention. Right-hand man of Captain Cameron in the job of patching smashed organisms amid the pandemonium of battle was Kenneth Seitner whose wife, Lillian, was waiting for his return in Dayton, Ohio. She waited in vain; Samaritan Seitner was killed in action.

There was a mud-splashed jeep which carried the wounded from Cameron’s aid station to a field hospital behind the lines. There were little holes in this jeep, put there by snipers along the road. The jeep came forward, empty, time after time; and seconds later it pulled out loaded with men on litters. And when the jeep balked after five such expeditions, its sun-blackened driver pitched in to guide those of the wounded who still could crawl or limp. “Here, buddy, put your arm ’round my shoulder… lean on it… hard… let’s try and see if we can make it together….” This driver’s name was Elmer C. Simpson, a surgeon’s aide from Denton, Texas.

The earth vibrated and the air was split. Strangling heat filled the valley. In the minds of grime-crusted men in battle there re mains no trace of the often-asked and never-answered question, “Why do we fight?” Reality was upon them and thinking stopped. They fought to stay alive — no more. There was an upsurge of a wild tenacity as old as life, teeth gnashing through abysmal weariness, a discarding of all hope and thoughts of home, a dull snarl of the protesting subconscious on the verge of shock. “Oh — oh, the bastards.” “Love” Company’s Captain Baker called for tanks. The tanks came. They blasted the shacks. They raked the strongpoints on the flanking ridges, then withdrew. There was little good they could do in terrain where a man could see far if he could see ten yards. Lieutenant Lewis F. Stearns of Champaign, Illinois, commanding the foremost platoon, drew back his men so that artillery might be registered on the resistance.

Colonel Newman came forward then, hard, slow, quiet. He ordered a cautious resumption of the advance, without artillery. Again the tanks rumbled to the front. Lieutenant Stearns deployed a squad on each side of the road to spearhead the assault. On he strode up the road, one tank in front of him, another tank to his immediate rear. The advance gained fifty yards — then Japanese fire forced the riflemen again to hug the mud. Stearns crouched in the roadside ditch. He wiped the sweat out of his eyes and reloaded his carbine.

“Hang on,” he encouraged his men. “Don’t give ’em an inch.”

Again “Red” Newman came forward.

“What’s the holdup here?” he asked.

“Better get down in the ditch, Colonel,” said Stearns.

Newman shook his head. “I’ll get the men going okay,” he said.

The colonel strode forward. Lieutenant Stearns leaped out of the ditch. He shouted to his men,

“Let’s go! The Colonel is here!”

The men rose from the ground. They followed their regimental commander in the assault. There was the wailing of an artillery shell, a flash and a crash, a revolt of earth and sky. The shell had hit the soldier nearest to “Red” Newman. The soldier was blown to bits. The concussion blew men across the ground as though they were leaves driven by a gust of wind. Lieutenant Stearns saw the colonel clutch his belly with both hands.

“Aid man! Aid man!”

A corpsman came running, bent low, his face almost between his knees. Colonel Newman lay on the Jaro-Carigara road. Crouched over him was his orderly, Carmelo Giacomazzo, the sculptor in wood. The Woodcarver pulled a knife and cut away the colonel’s clothing. Blood oozed from a gaping stomach wound. Then the aid man arrived with bandages and sulfa powder and Carmelo hastened through machine gun fire to get a jeep.

Aubrey S. Newman was calm. He was in complete command of his faculties. He did not move or struggle. He looked up into the faces of the men about him and he thought of the fight that must be won.

“Keep the troops in position,” he said evenly. “Send word back for mortar fire.”

“That won’t do,” Stearns shouted. “Colonel, can you hear me?”

“Yes.”

“Mortars are not enough — our men are getting killed every minute.”

The colonel lay still and thought. Guns jabbered and bullets whipped by. From the front came the cracking of grenades. His face was stony under the onrush of pain, but his eyes told that he was struggling to make a decision that would clear the situation. Finally he said:

‘Tell Colonel Postlethwait to call for artillery fire.”

Stearns dispatched a runner.

“Now,” growled Newman, “just leave me here and take care of those Japs.”

Stearns said, “I’ll be damned if I’ll leave you here.”

They wrapped their fallen commander into a poncho and dragged him into the ditch. Soon the Woodcarver came bumping up with a jeep. They lifted “Red” Newman into the jeep and the Woodcarver drove off as gently as a mother wheeling her injured child.[3]

The Battle of Jaro pounded on with unabated fury. Lieutenant Colonel Chester A. Dahlen, second in command, now led the Thirty-Fourth. His first order called for an artillery barrage; his second was, “Resume the attack.”

The barrage was lifted shortly after noon. Infantry attacked: “Item” Company on the right of the road, “King” Company on the left, tanks in the center. Riflemen waded across rice fields through waist-deep water. They attained the next bend in the road. But two hundred yards beyond the bend they were again halted by a wall of fire. Enemy artillery, machine guns, mortars and rifles were dug in on a ridge overlooking the highway. Further on the ground was dry, fields of sword grass going over into hillsides covered with tangled vegetation. The platoons fought on to get out of the water and the slime. Then they were pinned to the ground. Again they were forced to withdraw. Again the sweating cannoneers were called upon to plow the land ahead with steel and TNT. Long Toms, the Army’s biggest land guns, spoke.

Japanese shells disabled two Sherman tanks. A Jap gunner sent a 37 millimeter projectile crashing directly down the barrel of a tank’s 75. The tank gunner had just opened the breach to load his cannon. The enemy shot passed through the tube and through the gunner’s compartment and buried itself in the tank’s radio. Three men of the crew were smashed in the burst.

“Love” Company swung to the left to strike the stubborn strongholds from the flank. Five hundred yards from the road its aggressively advancing squads crossed an open field. They were struggling toward the far side of the ridge. But the enemy was on guard; his machine guns cut loose from dugouts hidden under thickets on the hillside. His bullets scythed the field. Here and there an American clawed the air, sagged, then sprawled heavily, arms and legs thrown wide as if in some macabre dance. The company was stalled in the open. No hollows or ditches were near in which to seek cover.

Captain Baker called for a radioman so that he might inform his commander of “Loves'” dilemma. A further advance was suicide, pure and simple. So was retreat across the fire-raked field. To remain in position meant gradual but certain annihilation. The radioman came, a private named John Wolf. He came through soul-withering fire. Strapped to his back was a radio. On the way Wolf fell, hit by a bullet. But he staggered back to his feet. Then he fell again, and another operator came forward to take his place.

Captain Baker radioed for artillery support. Meanwhile, his company’s machine guns pushed forward to throw out a curtain of lead under which his company could disengage. The machine gunners mounted their weapons on the unobstructed field. The Japanese replied by showering mortar shells on the machine guns. Sergeant Joseph E. Snipes of Eoline, Alabama, manned the first gun. Others followed; if Snipes could do it, they could, too. Snipes was wounded. Through clenched teeth he shouted insults at the Japs.

One of the machine gun crews fared badly. In rapid succession the gunner, the assistant gunner, and the ammunition bearer were hit. Only one man of that crew was left fit for action: Edward Prachazka of Downers Grove, Illinois. Prachazka did the work of four. He rolled the wounded out of the way and fired. In three minutes, more than three hundred bullets passed through the muzzle of his weapon.

“Love” Company withdrew. After that, the machine gunners withdrew. Though his gun was red hot, Prachazka picked it up together with what ammunition remained. Carrying a load designed for three he scrambled to safety across the death-ridden field.

Only one man now remained on the abandoned field. Private Thomas E. Mellinger, from Buffalo, realized the peril which threatened the machine gunners in their uncovered withdrawal. He stayed behind, firing his rifle at the Japs until the last machine gunner had slipped from sight.

But as Mellinger retreated, others again rushed forward, not to kill but to help. Private Darrel Winn of Osceola, Iowa, saw two soldiers struggling with a third whose legs had been badly hurt; he darted forward and helped. Private Jerome Bornstein of Madison, Wisconsin, crawled around the fire zone, tending the fallen. Private Morris W. Taylor, a messenger, whose home is in Coldwater, Michigan, saw a wounded buddy thrashing while a spray of bullets churned the earth around him. Taylor crept out and dragged the man into a clump of bushes. Meanwhile, not far away, a soldier named Narcisso Coronado from Center Point, Texas, had spotted a shack full of Japanese munitions; he fired tracer shells until the shack caught fire and exploded. At this point of the front the Japs jumped from their holes, milled in confusion, and disappeared.

That night the Division’s field artillery hurled four hundred and eighty-six rounds of high explosive into the Japanese lines north of Jaro.

(Continue to Chapter 10: Silence in Carigara)

_______________________________________

[1] Self-Propelled Mounts.

[2] The disposition of American troops fighting on Leyte at this time was as follows: The Twenty-Fourth Infantry Division advancing on Carigara from the south after its cross-island drive; the First Cavalry Division driving toward Carigara from the east; the Seventh and the Ninety-Sixth Infantry Divisions pushing across southern Leyte toward the Japanese base of Ormoc. Japanese forces dislodged from central Leyte were streaming both toward Carigara and Ormoc, the north and south gates, respectively, of the Ormoc Valley or Corridor.

[3] Months went by before Colonel Newman could rejoin the Division. But he returned in time to guide it through the difficult Mindanao campaign as its Chief of Staff.