Editor’s note: The following is extracted from American Leaders and Heroes, by Wilbur F. Gordy (published 1907)

….He was born in the southeastern part of England in 1727. From his father, who was an officer in the English army, he inherited a love for the soldier’s life. But in all the trials and dangers to which he was exposed in his short and stormy career, he continued to be a devoted son, his love for his mother being especially tender and sincere. With her he kept up a regular correspondence, in which he freely expressed his inmost thoughts and feelings.

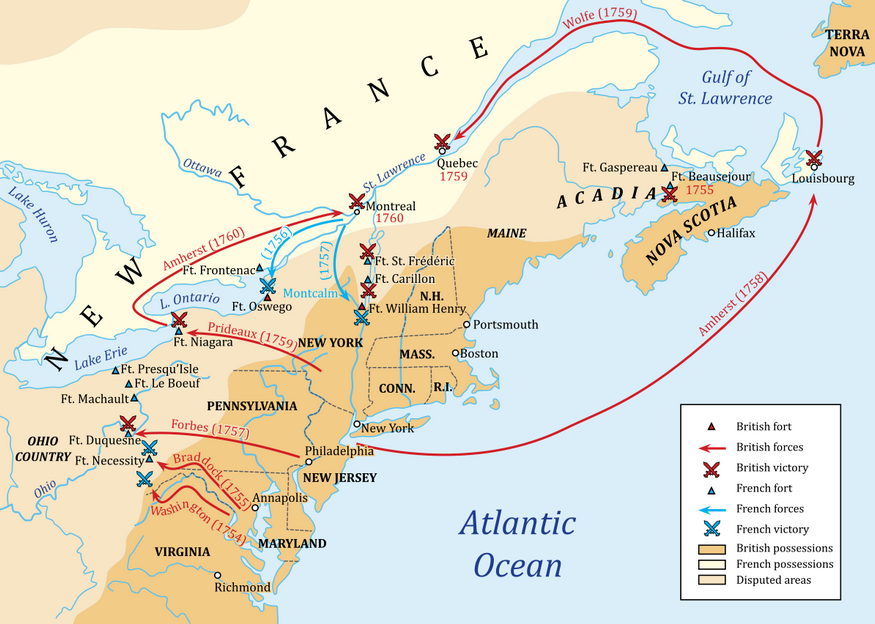

When only sixteen years of age he was sent to Flanders as an adjutant in a regiment of the English army. Here, by faithful and thorough work, he won promotion and soon, through bravery and skill, received an appointment as brigadier-general. At the age of thirty-two he was sent to America to assist in an expedition to Louisburg, and played a large part in the capture of that stronghold.

He presented an awkward figure. At that time he was tall and slender, with long limbs, narrow shoulders, and red hair tied in a queue behind. His face was plain, with receding chin and forehead, and up-turned nose. But his keen, bright eyes, full of energy and fearlessness, gave him an attractive countenance and revealed a heroic nature.

His health was never robust. As a child he was delicate, and as a youth he had frequent attacks of illness. But his resolute will and his high ideals enabled him to do what others of a different mould would never have attempted. He was governed, too, by an overmastering sense of duty, which was his most striking trait.

Although at times extremely impatient, his tenderness and frankness of nature easily won enduring friendships. His soldiers loved him so dearly that they were willing to follow him through any dangers to victory or death.

After the capture of Louisburg, Wolfe was so worn by the demands upon his strength that he returned to England and went to Bath for treatment. At this time he met Miss Katherine Lowther, to whom he soon became engaged.

But he was not long to remain inactive, for his country needed him. The great William Pitt, who had now become the head of affairs in England, saw in this fearless young general a fitting leader for a dangerous and difficult enterprise. This was an expedition against Quebec, the strongest and most important position held by the French in America.

The French army at Quebec, commanded by General Montcalm, numbered more than 16,000 men, consisting of Frenchmen, Canadians, and Indians. But some were boys of fifteen, and others old men of eighty. Here they awaited Wolfe, whose army numbered 9,000.

By June 21, 1759, Wolfe’s fleet lay at anchor in the north channel of the island of Orleans, not far below Quebec. Then began a time of trial and discouragement to the young commander, who vainly looked for a point from which he might hope to make a successful attack.

In the meantime his soldiers were suffering from intense heat and drenching rains. Much sickness was the natural result. Wolfe, anxious with doubt, himself fell a victim to a burning fever. But he would not give up. He said to his physician, “I know perfectly well you cannot cure me. But pray make me up so that I can be without pain for a few days, and able to do my duty. That is all I want.” Although racked with pain, he went from tent to tent among his men, trying to encourage them.

During several weeks there was fighting now and then in the neighborhood of Quebec. On July 31st Wolfe’s troops made a determined attack upon the French on the heights just north of the Montmorency River. The English advanced, in the face of a heavy, blinding rain, with great heroism, but were forced to retire without having gained a foothold.

Thus the summer wore on near to its close. In desperation, Wolfe decided upon a bold move. He determined to sail up the river, land above Quebec, scale the steep and rugged cliffs there, and compel the French to fight a battle or surrender the city.

The most serious difficulty was to find a way to scale the cliffs. At last one day came a glimmer of hope. For looking through a telescope from the south side of the river, the resolute young commander discovered a narrow path leading up the frowning heights not far from the town. “Here,” he quickly decided, “I will land my men.”

Promptly, eagerly, he began to lay his plans. On the morning of September 7th, in order to conceal from Montcalm their real purpose, the British, in gay red uniforms, embarked and sailed up and down the St. Lawrence, as if looking for a landing-place. On September 12th, the fatal time set for decisive action, some of the English vessels, with a large body of troops on board, hovered about the shore below Quebec, as if to force a landing there. Montcalm was completely deceived. The ruse had succeeded.

Meanwhile the main body of English troops, which was to make ready a landing, was quietly anchored in the river above Quebec. Twenty-four brave men volunteered as leaders to scale the cliffs. These men took their places in the foremost boat.

At two o’clock in the morning Wolfe gave the order to advance. It was a starlit night, but as there was no moon, it was dark enough to conceal the movements of the English. For two hours the long procession of boats filled with soldiers floated silently down the river. The brave young Wolfe, calm and masterful, was in one of the foremost boats. Fully expecting to be killed in the coming battle, he had, earlier in the evening, given to an old school-friend the portrait of his betrothed, Miss Lowther, which he had long worn about his neck. He said to his friend, “Give this to Miss Lowther, if I am killed.”

We can imagine the strain upon Wolfe’s feelings during the two hours in which the boats floated downstream. Perhaps it was to relieve this strain that he repeated in a quiet voice Gray’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard.” He seemed to dwell with peculiar feeling upon the last line in the following stanza:

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave,

Await alike the inevitable hour,

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

On coming to the end of the poem, he said, “Gentlemen, I would rather have written those lines than take Quebec.”

When they had almost reached their landing-place they heard a sudden call from a French sentry, “Qui vive!” “France,” replied one of Wolfe’s officers, who spoke French. “A quel régiment?” “De la Reine,” was the reply, and thinking the boats were under the control of Frenchmen carrying provisions to Montcalm, the sentry let them pass. Later when challenged by another sentry, the same English officer said in French: “Provision-boats. Don’t make a noise—the English will hear us.”

At length they came to the spot since called Wolfe’s Cove, and there landed. The twenty-four volunteers clambered up the path in the darkness and, reaching the top, surprised the small number of Frenchmen stationed there, and quickly overpowered them. It was with much difficulty that Wolfe’s army succeeded, by seizing hold of trees and bushes, in getting to the top with muskets, cannons, and supplies.

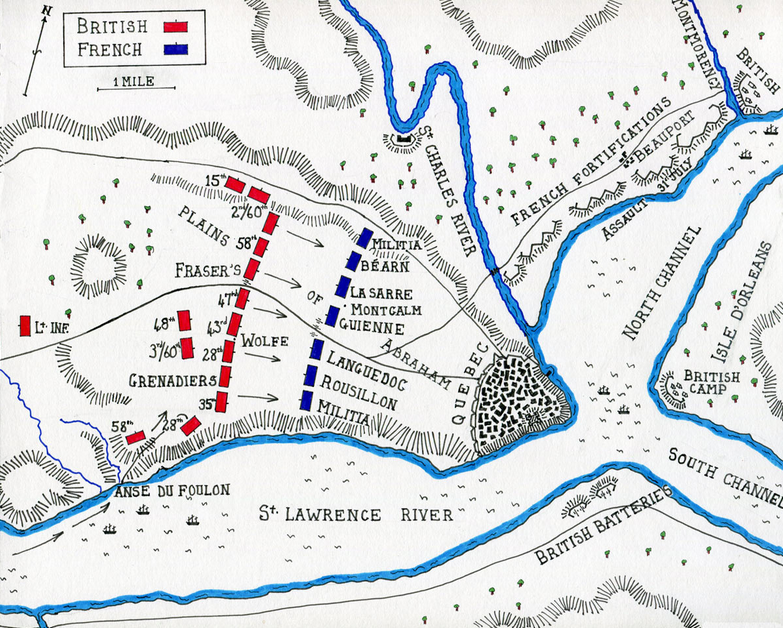

At daybreak, Wolfe chose as the field of battle the Plains of Abraham, a high stretch of land extending along the river just above the town.

The brave Montcalm, in doubt and perplexity, had spent a sleepless night pacing to and fro. When told of the landing of the English troops he rode up from his camp to see what was going on. Amazed at the “silent wall of red” presented by the English army drawn up in battle array, he said, “This is a serious business.”

Wolfe, anxious but calm, rode to and fro, inspiring his soldiers with confidence. “Victory or death” was their watchword, for in case of failure retreat was impossible.

By ten o’clock the French were in line of battle, ready for the onset. With loud shouts, they rushed upon the English. But the latter, waiting quietly until the enemy was only forty paces away, met them with a withering fire that strewed the ground with dead and dying men. While the French were wavering, the English fired another deadly volley, and then with victorious shouts rushed headlong upon the confused ranks.

The fighting was stubborn and furious, and Wolfe was in the thickest of the fray. While he was leading a charge, a bullet tore through his wrist. Quickly wrapping his handkerchief about the wound, he dashed forward until he was for the third time struck by a bullet, this time receiving a mortal wound. Four of his men bore him in their arms to the rear, and wished to send for a surgeon; but Wolfe said, “There’s no need; it’s all over with me.” A little later, hearing someone cry “They run; see how they run!” he asked, “Who runs?” “The enemy, sir. Egad, they give way everywhere!” Then said Wolfe in his last moments, “Now, God be praised. I will die in peace.”

Montcalm, too, died like a hero. Shot through the body, he was supported on either side as he passed through the town; but when he heard cries of distress and pity from his friends and followers, he said, “It’s nothing, it’s nothing; don’t be troubled for me, good friends.” Being told that he could not live many hours, he exclaimed, “Thank God, I shall not live to see Quebec surrendered.” A few days later Quebec came into the hands of the English. Its fall meant the loss to France of all her possessions in North America except two small islands for fishing-stations in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The treaty of peace at the end of the war, called the Last French War, was signed at Paris in 1763. By this treaty France ceded to Spain all the territory between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains; also the town of New Orleans, controlling the navigation of the Mississippi. To England she gave Canada and all the territory east of the Mississippi. Thus by a single final blow did Wolfe so weaken the hold of the French upon North America, as to compel them to give up practically all they had there.