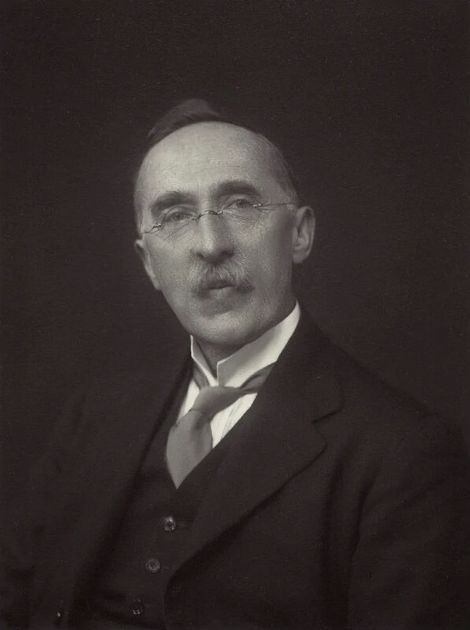

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from History and Historians in the Nineteenth Century, by G. P. Gooch (published 1913).

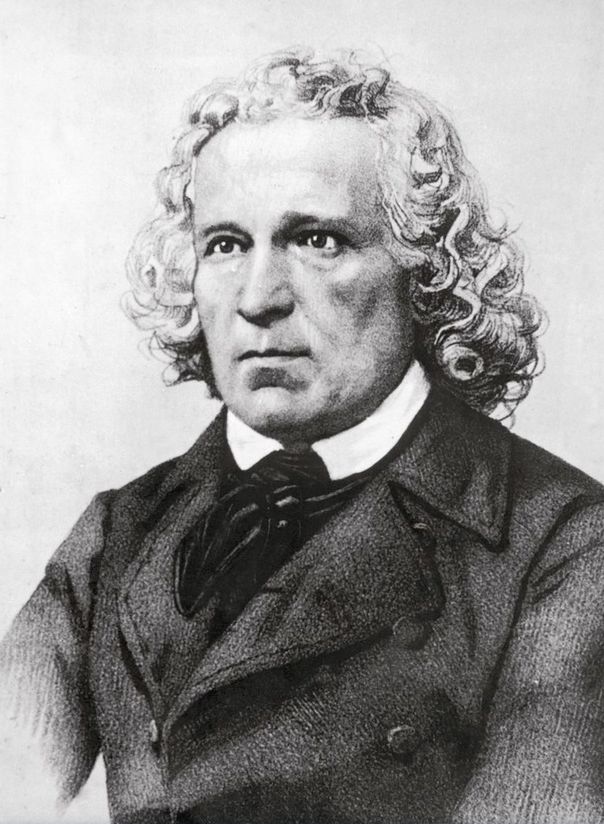

In the same wonderful decade which witnessed the earliest works of Niebuhr, Böckh, Savigny and Eichhorn, Jacob Grimm founded the science of Teutonic origins. Bodmer had published part of the Nibelungen, and some of the minor poets interested themselves in the Minnesinger; but the study of antiquities was thoroughly uncongenial to the Aufklärung. A new epoch opened with Herder, who paved the way for the historical study of literature by his conception of Nature-poetry, of the folk-soul, and of language as a treasure-house to which the centuries brought their contributions. He loved the childhood and youth of literature, the world of Homer, the Eddas and the Volkslieder. ‘I do not believe,’ he wrote in 1793, ‘that the Germans have less feeling than other nations for the merits of their ancestors. I think I see a time coming when we shall return more seriously to their achievements and learn to value our old gold.’ Herder’s interest came to be shared by a growing number of his countrymen as the romantic movement increased in volume. Johannes Müller described the Nibelungen as the German Homer, Bürger attempted to reproduce early models in his ballads, and Musäus utilised the sagas for his Tales. Tieck’s emotional personality found nurture in the songs and romances of the Middle Ages. August Schlegel’s lectures in Berlin declared war on the canons of the Aufklärung, and Von der Hagen was encouraged by them to publish old German poetry. Fouqué began a series of mediæval romances. Arnim and Brentano published their great collection of folk-songs known as the Wunderhorn, which brought back the Middle Ages in a flood and inspired a generation of German lyrists. The romanticists rendered a priceless service to historical studies. They enriched the imagination by their presentation of the many-coloured life of other ages and countries. They doubled the intellectual capital and widened the horizon of their time. But they were artists, poets, dreamers, not scholars, philologists, historians. It was the glory of Jacob Grimm that growing up in their circle he added to their best characteristics the critical scholarship and synthetic power which they lacked.

Born in Hesse in 1785, Grimm entered Marburg and, in obedience to the wish of his father, enrolled himself as a student of law. His intellectual interests were awakened by Savigny, who became his hero and model. ‘What can I say of his lectures,’ he wrote half a century later in his Autobiography, ‘except that they exercised a decisive influence on my whole life?’ It was to him that he dedicated the ‘Grammatik,’ declaring that his heart had longed to do public homage when he was able to offer something worthy of his old master. It was in his library that he made acquaintance with early German literature, and it was from him that he learned the historic piety which stamps the lifework of both teacher and pupil. If this friendship was the first most important event in his life, the second was the appearance of Tieck’s edition of the Minnelieder. Through Savigny he made the acquaintance of Arnim and Brentano, and the Wunderhorn was enriched from his stores. A fresh, almost uncultivated field, declared Grimm long afterwards, was before us. Goethe and Schiller had cared little for the Middle Ages. Bodmer had put the key in the lock, and the Romantics had turned it. When in 1805 Savigny took him to Paris to aid him in collecting material for the history of the Roman Law, he undertook researches on his own account. ‘I have been thinking,’ Wilhelm had written to his brother, ‘that you might look for old German poems among the manuscripts. Perhaps you might find something unknown and important.’ Soon after his return, he determined on a collection of German sagas and fairy-tales. He quickly discovered that many were international, and was forced to survey all Teutonic and Romance literatures, glancing also at those of the Slavonic world and the East. He drank deeply at the springs of Creuzer and Görres, and studied comparative grammar and early law. In these first few years of his intellectual awakening he mapped out the vast territories to the cultivation of which he was to devote his long and strenuous life.

Beginning with reviews and essays the brothers rapidly arrested the attention of scholars; and the ‘Mährchen,’ the first volume of which was published in 1812, made the name of Grimm a household word throughout Germany. The brothers accomplished for the fairy-tale what Arnim and Brentano had done for the Volkslied. Herder had remarked that a collection of children’s stories would be a Christmas present for the young people of the future. His forecast was fulfilled; but the main object of the work was to reveal the national wealth. The brothers strongly disapproved of the liberties which Arnim and Brentano took with their precious material. ‘They care nothing for a close, historical investigation,’ wrote Jacob to Wilhelm in 1809; ‘they are not content to leave the old as it is, but insist on transporting it to our own time, to which it does not belong.’ With their childlike natures and delight in folk-poetry the Grimms were ideal interpreters of the fairy-tale to the modern world. More than any other part of the romantic output the ‘Mährchen’ became part of the life of the German nation. The collection of German sagas which followed was less successful. Most were already in print, though a few were added from oral tradition. A strange mixture of Christian and heathen elements, of magic and history, they were of the utmost value as a revelation of the popular mind. Grimm declared that the earliest history of every people was the Folk-Saga, which was always epic. He agreed with Arnim’s dictum that epics composed themselves, and with the paradox of Novalis that there was more truth in the tales of the poets than in the chronicles. The Romanticists grasped the cardinal truth that the historian had to reconstruct the life and achievements of the peoples. History had neglected sagas and ballads because they contained no ‘facts.’ These views were powerfully expressed in the essay, ‘Thoughts on Myth, Epic and History’; but Grimm’s teaching was not without grave flaws. He attributed to the sagas more historical substance than they possessed. In his devotion to folk poetry he was unjust to other and later types. The conscious is reckoned inferior to the unconscious, individual work to the spontaneous creations of the community. He loved to regard mediæval literature, like mediæval cathedrals, as the anonymous expression of the soul of a people.

The repetition and development of the romanticist views of early literature led to a sharp criticism by August Schlegel, who ridiculed the contention that epics and folk-songs write themselves. That we do not know the author is no proof that they grew alone. The saga and the heroic lay were the common property, not the common product of their age. ‘When we see a lofty tower rising above the habitations of men, we know that many hands brought stones for its construction; but the stones are not the tower. That is the work of the architect.’ Without nature there is no life; but without art there is no form. All poetry is the combination of nature and art. Schlegel laughed at their reverence for the unimportant, their enthusiasm for old wives’ fables and nursery rhymes. In the latter criticism there lurks something of the arrogance of the Aufklärung; but the essay as a whole came like a keen, cool breeze. The indictment extended to Grimm’s etymology. The study of old German literature, he declared, could only succeed if based on exact grammatical knowledge. Grimm felt the justice of the criticism and began to turn to grammatical studies. Rask, whose Icelandic grammar he had praised on its appearance in 1811, had said that philology should not so much decree how words should be formed as describe how they had been formed and altered. This principle found a ready response in Grimm, who entertained the same reverence for language as for folk-poetry. The grammarian must be the student, not the teacher of language. Writing in the noonday of the Aufklärung, Adelung despised dialects and constrained the language with bit and bridle. Others urged the expulsion of certain words and the alteration of many more. The attack on ancient forms was as repugnant to Grimm as an outrage on morals. The production of bald uniformity was like the method of the Terrorists in the French Revolution; and the fabrication of new words was a sin. It was the wrinkles and warts that gave the incommunicable stamp of home, as on a familiar face. In place of learned pedantry and levelling reform he offered historical grammar, which taught respect for every living element.

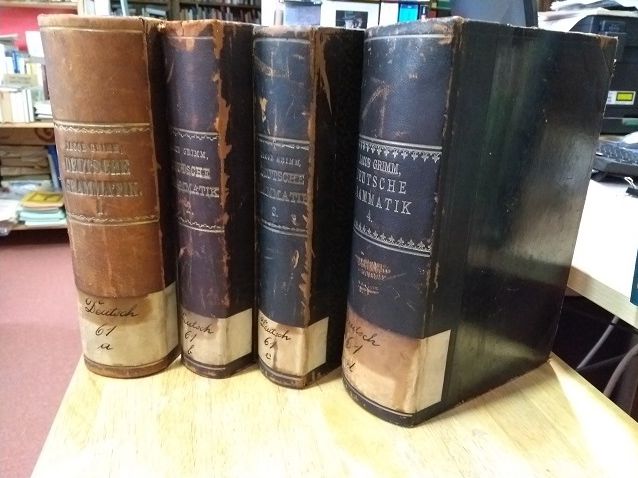

The laws of language had been outlined by Wilhelm Humboldt in 1812 in his masterly essay on the Basques. He urged the combination of the study of language and history, and the investigation of the characteristics of nations as the necessary accompaniment of grammar. The structure of language was organic; but its formation was disturbed by borrowings and imperfect assimilations. Thus every language consisted of organic parts and inorganic accretions. These ideas were adopted by Grimm in his German Grammar, the first volume of which appeared in 1819. The purpose of the book was to reveal the operation of law in language as in history; and the key could only be recovered by careful comparison of all Teutonic languages and dialects. His chief thesis was that all the families of German speech were closely related and that the present forms were unintelligible without a reference to the oldest. He made full use of the work of his predecessors, above all of Hickes and Rask, and, in another field, of Bopp; but he introduced the comparative method into Teutonic philology. In the purely German territory he had to lay the foundations himself; and an architectural whole appeared where there had been nothing but isolated details. The book gave far more than its title suggested, for it was in truth a history of the Teutonic languages. Grimm’s masterpiece formed one of the instruments by which historical science has ever since made its advance. The most competent of judges, Benecke, declared that he did not know whether most to admire the author’s insight or knowledge. His old critic, Schlegel, hastened to express his congratulations. Following his guide the reader rejoices in the ever-increasing light, till an ordered world meets his gaze.

The work was out of print in a year, and in 1820 its author began to rewrite it. He made new and important discoveries as he worked, and the printed sheets were revised by Lachmann. The arrangement of material was improved, and the second edition was in many respects a new work. The most important addition was the statement of ‘Grimm’s Law,’ or the explanation of the changes of letters. There were laws of sound. No words could be traced to a common origin unless the differences in their sounds could be explained by a law of variation. In this way the relations of peoples could be recovered, and some knowledge of the early life of humanity be obtained. Three further volumes of the ‘Grammatik” were published, the latest attacking the problem of syntax. When the publisher inquired whether Grimm preferred to complete or to revise his work, he chose the latter. Though incomplete, it is beyond comparison the most important work ever devoted to German philology. No one had ever penetrated so deep into the innermost recesses of language and seized its intimate relation to life. In becoming a philologist Grimm did not cease to be a poet. His creative insight is continually flashing light on dark places. Adelung had asked what sense there could be in giving a sex to lifeless things and abstract conceptions. Grimm answers by trying to retrace paths along which primitive fancy moved. In its early forms language is concrete and pictorial; in its later, abstract and intellectual. This view of the transition from the sensible to the rational was a weighty contribution to the history of mankind.

Between the first two and the last two volumes of the ‘Grammatik’ Grimm published his marvellous work on Legal Antiquities, a picture of early German life from a particular angle. The differences he had shown to exist between the early and later stages of literature and language existed equally in the realm of law and religion. He had warmly adopted Savigny’s view of the nature of the law and had hailed the ‘Vocation‘ with delight. He was especially interested in symbolic actions, the forms in which conceptions expressed themselves. In an early essay on Poetry in Law, he had declared that they had grown in one bed. The poet and the judge alike uttered the common thoughts. He was unjustly accused of failing to treat the subject historically or to trace the gradual transformation of institutions. But his task was wholly different from that of Eichhorn. He confined himself to the sensible, the visible, the pictorial element, the customs and uses, the actions and forms which an unlettered age demanded. His chief authorities were the so-called Weistümer, or dooms, and early literature and legend. No jurist could have written the book, for no jurist possessed the requisite knowledge of the languages and literatures of the mediæval Teutonic world. While Eichhorn desired to discuss the foundations of modern law and practice, Grimm never troubled himself about later developments. Every usage possessed its importance as an expression of the folk-spirit.

The book was hailed with delight by the jurists of Germany. Savigny rejoiced in the brilliant development given to his own teaching. Eichhorn was warm in his praise, without realising to the full extent its creative character. Michelet gave intense satisfaction to the modest author by building his own ‘Symbolic Origins of French Law’ on its foundations. Grimm truly declared that his book was a work of suggestion. Its suggestiveness is still unexhausted nearly a century after its appearance, and its influence may be traced in every subsequent writer on early Teutonic law. Closely allied to Legal Antiquities was the edition of Weistümer, or dooms, of which four volumes appeared during his life and three others after his death. ‘Unless I am blinded by enthusiasm,’ he wrote, ‘this collection will enormously enrich and almost revolutionise our legal antiquities, make important contributions to a knowledge of law, mythology and customs, and give warmth and colour to our early history.’ They played the same part in law as folk-songs and fairy-tales in mythology and poetry. In both cases he used popular tradition to illustrate and explain written memorials. But the earliest date from the thirteenth century; and he was at fault in employing them as illustrations of far earlier times.

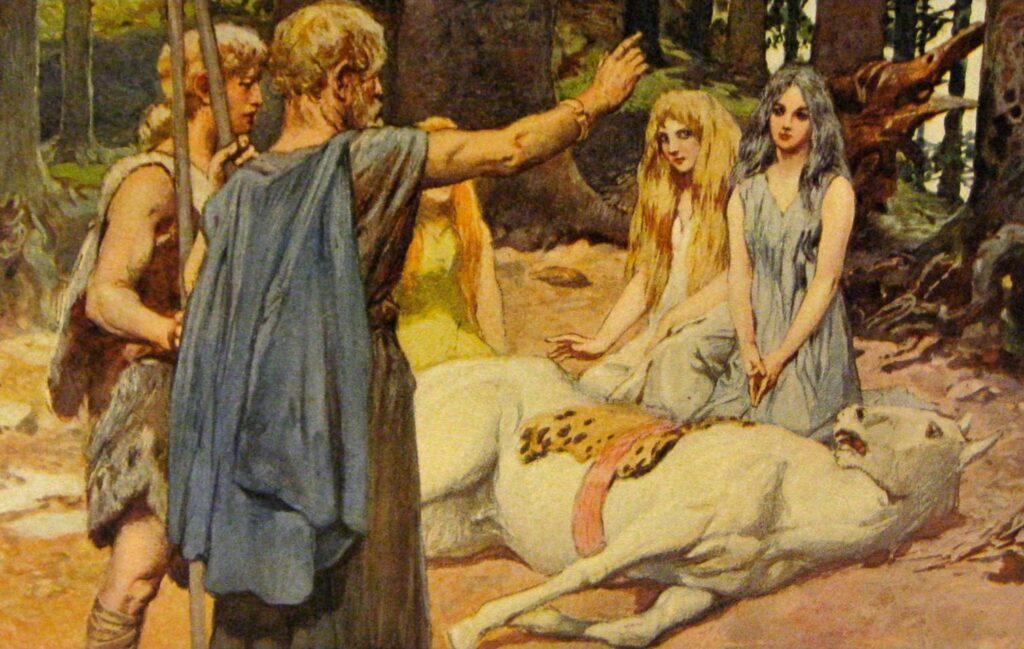

A further aspect of early Teutonic life was explored in the ‘German Mythology.’ Görres and Mone had studied the survival of heathen practice and belief without employing critical methods. ‘In my books,’ declared Grimm in the preface, ‘I have tried to show that the language of our ancestors was not rough and wild but fine and harmonious; that they did not live in hordes but were free, moral and observant of law. I now desire to exhibit their hearts full of belief, to recall their magnificent if imperfect conception of higher beings.’ Literature, sagas, fairy-tales, customs, language were made to yield their contribution, and a mass of oral matter was collected. The old world revived with its brilliant colouring and fantastic shapes. The stage was crowded with gods, swan-maidens, nixies, cobolds, elfs, dwarfs and giants. Mythology being a creation of the poetical spirit, the talent of Grimm was peculiarly fitted to deal with it. The introduction unfolds a great picture of Christianity spreading over Europe, while heathenism retreats step by step. Beginning with the gods, we pass to the lesser mythological beings, to the elements and the seasons in relation to human life, to the personality of animals and plants. The world of light is paralleled by the world of darkness, by demons, witches and magicians. The ‘German Mythology’ took its place among the classics of European scholarship. But though it is often regarded as his most perfect work, and though its vitality and insight are marvellous, it is not without serious faults. The picture of Teutonic civilisation is too rosy, and he credits early times with many customs and beliefs of subsequent growth. A few years later considerable portions were rendered antiquated by Adalbert Kuhn’s researches in Indo-Germanic mythology and by Mannhardt’s investigations into popular cults. Yet it was nonetheless the foundation on which the science of Teutonic heathenism has been reared, and holds an honored place beside the Grammar and the Legal Antiquities among the works which recreated ancient Germany.

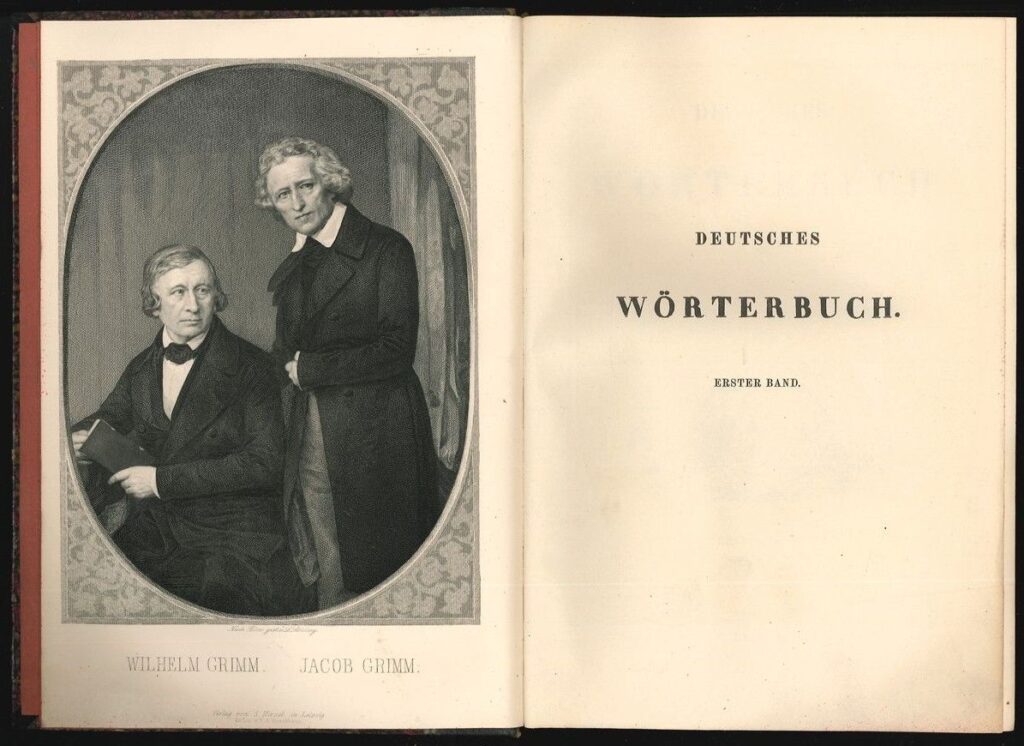

Grimm’s later life was chiefly occupied by linguistic studies. His ‘History of the German Language,’ published in 1848, was rather a series of dissertations than a connected narrative, and may almost be described as an appendix to the Grammar. A good many of the results of the earlier work were modified in consequence of the works of Bopp and Pott. The researches of Zeuss had interested him in ethnography; and though parts of the work are fantastic and some of its identifications of early tribes incorrect, the attempt to throw the light of philology on ethnology and culture was not without importance. The German Dictionary, the last great task of his life, was suggested to the brothers by a publisher, and accepted by them in return for a living wage. It was to include all words from the age of Luther to the age of Goethe. The first part appeared in 1852, and the letter ‘F’ had been almost completed when Jacob Grimm died in 1863, full of years and honours. ‘All my works,’ he wrote in one of his last essays, ‘relate to the Fatherland, from whose soil they derive their strength.’ These simple words may serve as an epitaph for one who was at once a great patriot and a great scholar, and who carried through life the heart of a little child.

Jacob’s earliest and most effective helper was his brother Wilhelm. Their studies began together at Marburg, and their publications were joint till the elder brother turned his attention seriously to grammar. During the middle decades of their lives their paths led in different directions; but their closing years witnessed a renewal of co-operation. The Dictionary is no less a memorial to their joint labours than the ‘Mährchen.’ In addition to the works in which he assisted his greater brother, Wilhelm’s independent production was of the highest value. His greatest achievement was his study of the German heroic saga. His scope was far narrower than that of his brother. It was his instinct rather to select a limited territory and to examine every corner of it with loving care than to roam over immense tracts of country. He lacked the creative genius of Jacob; but he was the more exact and careful worker. The relations of the brothers form one of the idylls in the history of scholarship, and they remain associated in the memory as they appear in the frontispiece of the Dictionary. They loved the German people, and their love has been richly repaid. They rank immediately after Goethe and Schiller among the spiritual influences which have made Germans all over the world conscious of their unity.

The Grimms grew out of the romantic circle; but they owed less to any of its members than to Benecke, librarian and Professor at Göttingen, who was the first to make lectures on early German literature and language part of the ordinary curriculum. He assisted the brothers in their early researches, lending them books from the library, and encouraging them by favourable reviews. His first important publication was an edition of the fables of Bonerius, which marks the beginning of scientific lexicography. His talent was philological rather than literary; but in this sphere his achievement was unrivalled. Each word was examined in its historical development, and the finest shades of meaning extracted. Each monument of early poetry was studied in the light of its time and place. Benecke was not only, in the words of Jacob Grimm, the inaugurator of grammatical knowledge of early German literature at the Universities, but also the founder of the strictly historical method of studying this branch of literature, which had hitherto been judged by æsthetic standards.

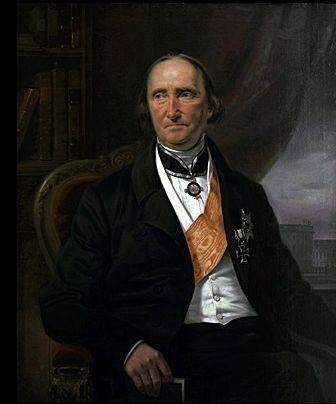

While many philologists rendered valuable assistance, Lachmann shares with Jacob Grimm the honour of ranking as the joint founder of the scientific study of early German literature and language. Born eight years after Grimm, he learned exact philology under Hermann at Leipzig, and owed his initiation into Teutonic studies to Benecke. ‘As Benecke lectured year in, year out, on the poetry of the thirteenth century,’ he said later, ‘I felt stimulated to learn old German.’ At the same time he continued his classical studies, and aged Heyne foresaw his pupil’s greatness. His edition of Propertius contained the germ of all his future achievements in different departments of philology. His aim was the reconstruction of the text as the author wrote it, on the authority of the best manuscripts. The emendations in which philologists rejoiced were not to be thought of till the manuscripts had been examined. In 1816 he turned to the Nibelungen, the present form of which he attributed to the thirteenth century. He gradually obtained an unequalled insight into the metric and philological characteristics of mediæval poetry, reconstructing texts from an exhaustive study of all available manuscripts. The ‘Grammatik’ was warmly welcomed, Lachmann declaring it put them all to shame for their ignorance. The two men now entered into close relations, and in his preface to the second edition Grimm declared that it was impossible to describe the help of Benecke and Lachmann. ‘Such full and open communications as Lachmann has vouchsafed me must have been experienced for their value to be understood.’

When Lachmann was appointed to a Chair in Berlin in 1824, he had acquired an incomparable knowledge of the printed and manuscript sources of early German literature, which enabled him to pour forth critical masterpieces in rapid succession. His first work was Hartmann’s ‘Iwein,’ for which Benecke gave him his collections, and which he boldly declared to be the first critical edition of an old German poem. The ‘Iwein’ was followed by an edition of Walther von der Vogelweide, which first made the poet intelligible, and by the works of Wolfram. ‘My aim,’ he declared, ‘was to make visible one of the greatest poets in his full splendour.’ Returning to the Nibelungen he published the text in 1826 and his critical investigations ten years later. It was possible, he contended, to trace twenty separate songs; but his reconstruction of the poem was widely attacked. Into the field of German literature, as into Homeric studies and New Testament criticism, Lachmann brought fruitful ideas which, even when not accepted in their entirety, opened up new horizons and worked like a leaven long after his premature death. In his obituary notice Grimm declared the philologists were of two classes—those who studied words for the sake of things and those who studied things for the sake of words. He himself belonged to the former, Lachmann to the latter. ‘Born to be an editor,’ he added, ‘Germany has never seen his equal.’ He made a history of mediæval German literature possible. His true master was Bentley, whom he pronounced, ‘the greatest critic of modern times.’ But while Bentley sometimes reached his most brilliant results by a flash of genius, Lachmann won his triumphs by incredible industry and insight into the variations of language and metre. While Grimm failed as a Professor and founded no school, Lachmann’s lectures were the starting-point of many a career. Otto Jahn dedicated his first important work to his ‘incomparable teacher.’ Simrock’s versions of the mediæval classics were built on his foundations. Moritz Haupt, his successor and literary executor, worshipped him as the supreme master. Though he was in no sense an historian, he supplied historians with a key to large tracts of the life and thought of mediæval Germany.