Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 17 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 16: Another Half Million Coconuts)

____________________________________________________________________

The Island deemed secured, Colonel Verbeck relaxed. A native padre approached him.

“Please,” said the servant of the church, “could you do something about cleaning out the Japanese in Lubang town?”

The colonel sat erect.

“What? Still Japs in Lubang?”

“But there are many,” the padre said mildly. “They are all over the town.”

The colonel called a company commander. He arranged for a force to go in and destroy the remaining enemy.

“Colonel — I don’t know…,” faltered the priest “You see, those Japanese are all dead.”

(from a Field Report)

__________________________________________________________________________

It has ever been the infantryman’s lot to experience the worst traits of the countryside he captures. The supposed glamor of life on tropical isles seems somehow hinged to the presence of ice boxes, pith helmets, broad verandahs and saronged shapes; instead the infantryman drank swamp water tasting of chlorine and dead insects, wore hot steel on his head instead of cork, sat in steaming earth holes instead of on cool verandahs. (“Nice” people and the comfort that goes with them seem to vanish everywhere into thin air when infantrymen move in.) Of all the ruined and inhospitable places in the Philippines, the dogface found big Mindoro Island the hottest, dustiest, most boresome and malaria-infested.

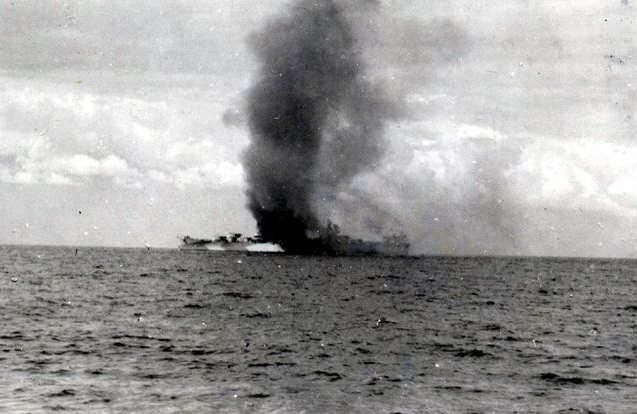

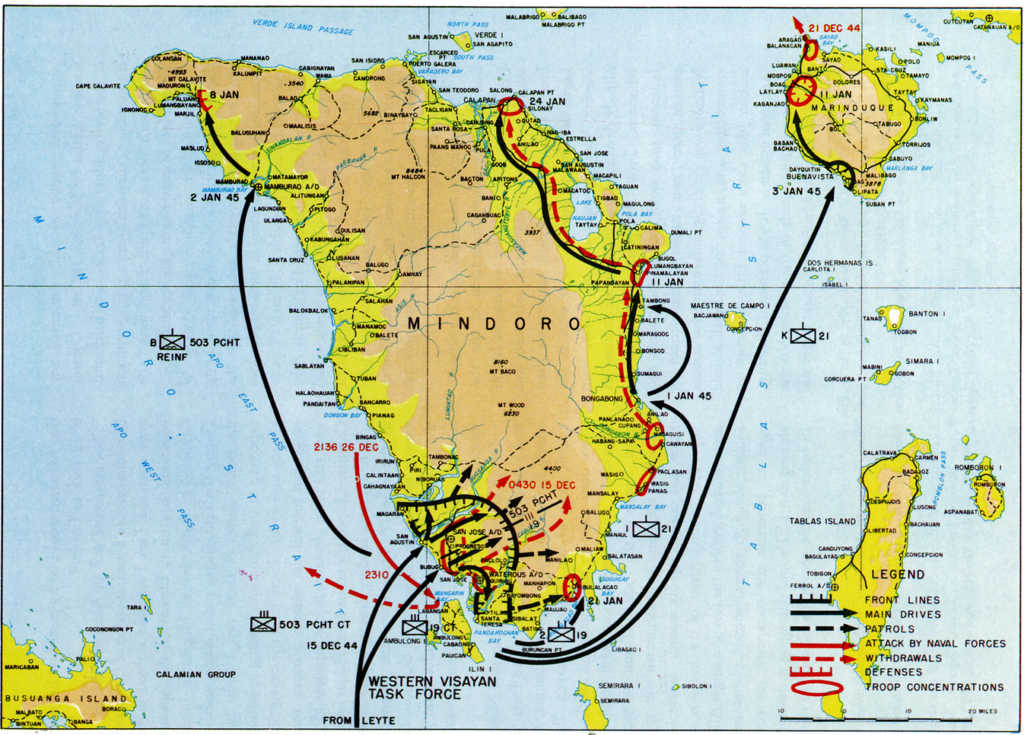

On December 15, 1944, the Division’s Nineteenth Infantry Regiment invaded Mindoro at its south-western tip. On the way from Leyte a Japanese suicide bomber crashed into a convoy escort ship, the Nashville. The bomber exploded and the ammunition aboard the cruiser exploded. More than a hundred Americans died, and other hundreds were wounded even before the landing. Infantry aboard the convoy vessels were glum. Everyone expected a hard fight on the beaches of San Jose Bay.

But the landing was unopposed. The assault teams rushed up the beaches and not a shot was fired. Riflemen combed the town of San Jose. They found one Japanese soldier and he was drunk. South of the town a patrol surprised three Jap naval men operating a radio station. The patrol killed one and captured the others. A smiling Austrian missionary emerged from hiding. Father Johann Steiger reported that the Japanese garrison had fled into the mountains when the convoy hove into sight.

The men of the “Rock of Chickamauga” looked at the summits to the north and east of San Jose. The mountains were high, naked, barren volcanic rock. The valleys between the mountains were beds of purple volcanic sand. Upon this promise of exertion the sun beat hotter than the sun of New Guinea.

A few days later the Division’s Twenty-First Infantry Regiment landed on the north coast of Mindoro near the town of Calapan. Here, also, the beach was undefended. Natives reported that the Japanese, after a hurried saturnalia of rape, robbery, and murder, had fled into the hills.

The soldiers of the Twenty-First looked at the hills. They were steep and heavily wooded, and in the distance the peaks rose higher and higher under a gloomy sea of jungle. The sky was gray and heavy with rain. More distant mountains hid their summits in the clouds.

From the first hour of the Mindoro landing, enemy warplanes from Luzon bombed and strafed the beaches in a daily routine. Japanese warships appeared and bombarded San Jose on December 27. During the nocturnal shelling infantrymen stood up on the sands and watched in awesome silence when they saw an American pursuit pilot crash his Lightning into a Jap cruiser. American bombers from Leyte came to the landing teams’ rescue. They sank several Japanese destroyers and drove Nippon’s larger warcraft back into hiding. After that the Mindoro campaign wore on through four months of forced marches, mountain raids, heat exhaustion, jungle rot and malaria. Five hundred and ninety-three Japanese were killed by the Division’s riflemen on this island. Seventy-three enemies surrendered alive. The first American killed on Mindoro was killed by an angry carabao.

Simultaneously with the Mindoro raid, a small Division task force struck Marinduque, off the south coast of Luzon. Marinduque Island proved to be a well-stocked refuge for rich Filipino and Chinese merchants from Manila. Eighteen forlorn Japs were rooted from their hiding places and killed. Mindoro and Marinduque were the first stepping stones from Leyte to Manila and Luzon. Their control meant domination of the main sea route through the islands. Mindoro’s airfields, built hard in the wake of the infantry advance, became the nemesis of enemy shipping in the China Sea.

There was a bitter fight in the town of Paluan, on Mindoro. There was another fight near the village of Bulalacao. But in the town of Pinomalayan, after a band of thieving Japanese had been destroyed, the populace invited the Americans to a banquet. Children and young women fashioned a robe of flowers and they made Private Lawrence Nathan from Highland Park, Michigan, wear this robe. Rifleman Nathan was dazed, for this day happened to be his birthday.

He was led down the village street to a throne-like chair built from bamboo poles. Following him was a parade of dancing, chanting men and women, the beating of drums, and strumming of guitars. Nathan was seated on the throne. The mayor of the barrio approached the throne and placed a crown of hibiscus flowers on the soldier’s head. Then he pronounced him “King of Pinomalayan.” Nathan grinned. Coached by the sinewy school mistress, the natives sang “God Bless America.” The mayor then asked the “king” to sing. After a brief pause Nathan broke the silence with a raucous version of “I Want a Paper Doll That I Can Call My Own.”

The seven hundred Japanese who were on Mindoro were utterly surprised when the invasion struck them. Their garrisons in the coastal towns were unable to unite into a striking force. They abandoned the towns and took to banditry in the mountainous interior. They had no food, medicines, or contact with Japan. Their groups broke up into lesser groups which plundered, raped and burned almost at will. Mindoro is vast and wild. Much of its interior has never been explored. Guerillas were unable to cope with the machine guns of Jap marauders. For the Division’s patrols it was slow, painfully difficult work to corner these bands where they could be destroyed.

The task was complicated by numerous guerilla bands operating with a sort of Robin Hood independence. Guerillas established concentration camps for all those who did not agree with them. The formula was to accuse their victims and rivals of collaboration with the Japanese. Roads were few and far between; supply lines were dependent on native carriers or animal pack trains. There was much confusion in the towns as temperamental faction leaders quarreled over offices of power and charged one another with being Jap spies.

Through this atmosphere of local squabbles and confusion moved American combat patrols and Signal Corps crews intent on securing Mindoro as a base and nerve center for decisive undertakings in the future. Typical of countless exploits by small groups during the West Visayan campaign is the story of Sergeant Joe Nicksich of Pueblo, Colorado.

Six feet of upright bone and muscle, dauntless cheer and panther strength, this one-time mill worker led a crew of one time farmers, painters and welders on a five weeks’ trek through unexplored desolation. They vanished into Mindoro at San Jose in the south, and nothing was heard of them until they materialized again at Calapan in the north. Their mission was the extermination of Japanese banditry in the interior.

Joe Nicksich was the leader of a mortar section — two mortars and twelve men, reinforced by a pitch-and-toss assembly of guerillas — detached for “special duty.” Nicksich liked adventure. He also liked mortars. On Red Beach in Leyte he had been the first soldier of the invasion who captured a Japanese mortar and turned it against the foe. To his mortarmen he said, “We’re going on a junket. We’re going to travel light.”

He supervised the cleaning of their mortars, and he drew their store of shells and rations, and then he broke down the whole load into “one man carries.” His picturesque task force traversed the belt of palms and meadow lands on the coast, and pushed in single file into the mountains beyond: native warriors in the van, then Nicksich at the head of his mortarmen, followed by a carrier train. Another detachment of guerillas protected the rear.

They trudged on, day after day. They followed the dry stream beds and the saddles, lugging their mortar tubes, their bipods and butt plates, their ammunition load and jungle packs through dust and sunlight. They crossed vast expanses of volcanic sands; they panted over razorback ridges. On the rainy northern half of Mindoro they pushed through thickets, and virgin forest and across many swollen streams. Nicksich was well aware of the vulnerability of his slow-moving column. An unseen enemy machine gun could have erased his caravan in a matter of minutes. But the sergeant was ever alert. In open country his scouts were a mile out in front. Flank patrols moved silently along the hill sides to his right and left. Here and there they sighted Jap food-stealing parties or a secret Jap bivouac — things they had set out to find. But not once were they surprised.

At times they traveled astride lumbering carabao oxen. The massive black beasts, progressing at about one mile an hour, were wont to halt at every stream to wallow in mud. Nicksich and his aides eliminated many of these stoppages by carrying helmets full of water and mud. Whenever the water buffaloes showed intentions of meandering off their course, the mortarmen doused the animals’ big heads with water and administered mudpacks — and the carabao, appeased, proceeded.

At other times Nicksich and his crew pushed on, riding shaggy native ponies, or in ancient two-wheeled carts supplied them by barrio patriots. But most often they walked. To the villagers along their plodding course they were the vanguard of liberation from banditry by demoralized Japanese and gangs of “good neighbors.”

“Japs over there.”

A tawny arm pointed to a sector of the purple ranges. Some times such intelligence would come from women visiting friends in a neighboring barrio. At other times it would come from children playing on the porch of a bamboo hut; or from a farmer whose pigs had been stolen at dawn.

Barefooted scouts prowled forward. Dusk falling, and their bellies full, the Japs became careless. Again and again the Coloradoan and his haphazard force surrounded groups of loafing Japs, shredded Jap delusions of safety with sudden mortar barrages. Then came hails of lead followed by a fleet guerilla charge. The Japs were buried and Nicksich handed their rifles to farmers’ sons who had never held a rifle before.

The new guerillas would nod fiercely and brandish their weapons. Nicksich would show them how to load their rifles, how to operate the safety mechanism, how to aim and to fire. After an hour of such basic training the expedition would move on to other tasks.

On one occasion Nicksich’s force raided a barrio and killed forty Japs who were too drunk from sake to run, but not too drunk to fight. But then another force of sixty Japanese came down a ravine. Nicksich sealed off the mouth of the ravine with a pattern of mortar bursts. The Japs, too, had mortars; they set the village afire.

Nicksich rallied the fleeing villagers. Men, women and children helped the guerillas to carry mortars and ammunition to the hillsides flanking the ravine. Caught in a cross fire of mortar shells and rifle fire, the Japanese dispersed. The villagers celebrated among the smoldering ruins of their homes.

Bamboo houses are easily rebuilt.

Village communities received the wandering mortarmen with jubilation. Crusted with sweat and dust as they were, they were promptly dragged to feasts. Suckling pigs roasted over backyard fires. Chickens long hidden in caves were brought to light and killed. There was fruit, and fish in the streams. Householders presented palm wine in bamboo log containers and with smiling dignity. Then the night was one of well-being. Old and young strummed guitars. Girls danced with guerillas until dawn. There was love-making in the huts. Two hundred yards out the sentries watched, motionless and wide-awake.

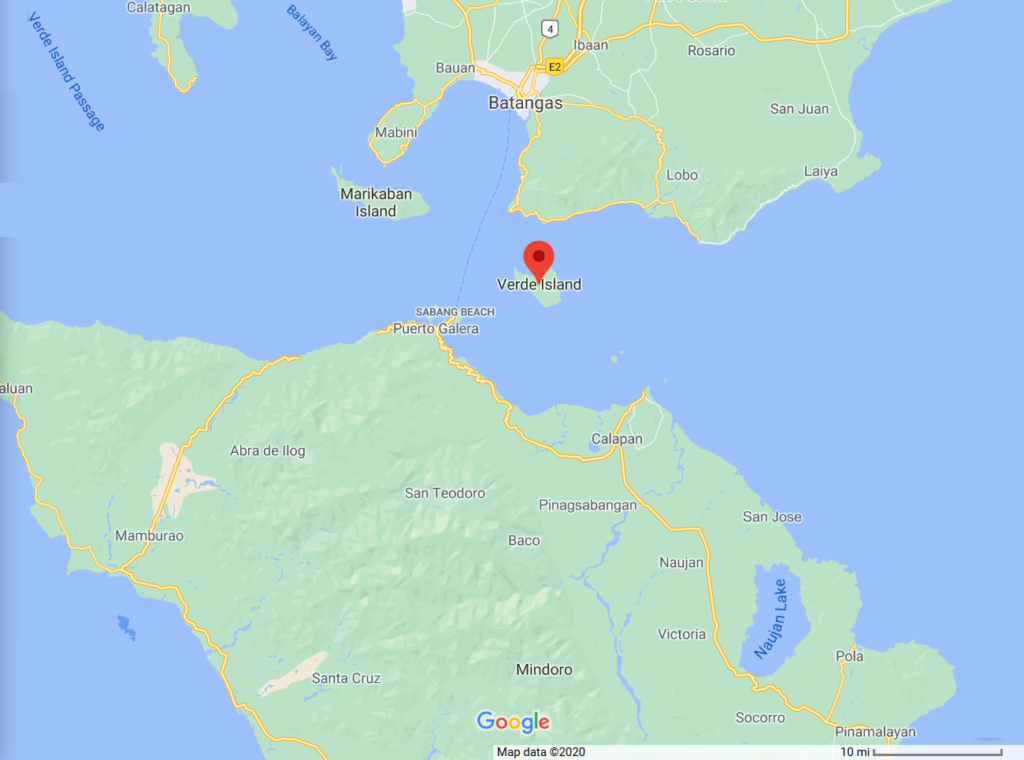

When Joe Nicksich’s expedition arrived at Calapan, they heard of Jap trouble on the small island of Verde, ten miles to the north.

The Japanese had shipped artillery to Verde Island. The heavy guns were mounted on a height named Mickey Mouse Hill, and they were a threat to shipping through Verde Straits which separated the smaller island from Mindoro. The Japs there also had a radio station which spied on planes and ships moving in the direction of Luzon.

On February 23, 1945, a task force of Nineteenth Infantry Regiment teams and guerillas had invaded Verde. They had scoured the island, fought a number of skirmishes, and departed two days later, leaving local guerillas in charge.

The guerillas soon messaged for help. Their message spoke of Japanese artillery and machine guns in action, against which the lightly armed natives were helpless. Joe Nicksich and his mortarmen were ordered to go to Verde to knock out the enemy artillery on Mickey Mouse Hill.

The sergeant asked for a ship to carry him across. No ship was available. “Get some canoes,” Nicksich was told, “and paddle across.”

The Coloradoan and his crew requisitioned two hollow-log canoes. They loaded their mortars and ammunition, filled the canoes with guerillas, and paddled off.

The night was dark and windy. Approaching Verde the mortarmen heard the booming of a heavy surf. In the darkness the canoes were thrown athwart the seas. The craft’s outriggers were knocked away by the surf and the craft capsized. Mortarmen and guerillas swam to the beach. Their weapons had spilled into ten feet of water.

Joe Nicksich scratched his ears. His mortars were gone.

But as though his curses had been prayers, help appeared. A local guerilla chief, saturnine and squat, emerged from the jungled hillside. “Let me help you,” he said.

He disappeared, and soon he returned with a swarm of young men.

“Divers,” he announced.

Divers they were. Within an hour they retrieved every weapon and every shell that had been lost in the sea. Then they all crowded around Joe Nicksich.

“Fix the Japs,” they demanded. “We show you where the guns are.”

Nicksich laughed. “Take it easy,” he told them, “and don’t make so much noise.”

‘Will you fix the Japanese guns?”

“I shall fix them,” Nicksich promised.

They camped in a gully. On February 28, also by native banca, there arrived Major George W. Dickerson of Warrenton, Virginia. He assumed command of “all American and Guerilla forces on Verde Island.”

An air bombardment of Mickey Mouse Hill was planned for 11 A.M. Nicksich’s mortars were to mark the target area with smoke shells. But on their canoe voyage from Mindoro wind and currents had carried the mortarmen off their course.

The landing had been made at the wrong spot. The mortars could not be carried into position in time to fire the smoke shells.

Promptly at 11 A.M. the planes winged in over Verde Island. They bombed the wrong hill.

Major Dickerson posted guards on strategic shore points and trail crossings. Then he led his mortarmen and guerillas through rugged jungle to a point eight hundred yards from Mickey Mouse Hill. It was a night march by compass, through inky darkness. The task force arrived at midnight and camped in a ravine. Plans for the next day’s action were discussed. A mortar barrage was to be placed on the Jap artillery positions and the guerillas were to charge the hill.

In his Field Report, Major Dickerson relates:

“At daybreak on 1 March the mortars were set up and an observation post established on the forward slope of a hill overlooking the Jap position. The enemy guns and installations were cleverly concealed, and we could not locate them through our field glasses. The guerilla leaders were then called forward to point out the Jap positions, but even they were in doubt as to their exact location.

“Our observation post became like a beehive. The crowd of Filipinos anxious to help us made a large volume of noise. Evidently we were spotted by the Japs, for we were soon under fire from one of the belching bolt machines, canister ammunition. We were now able to pin-point the 75 millimeter gun and immediately began bracketing in on it with our 81 millimeter mortars. Smoke was used until we got the proper range. As we fired for effect, we could see that the mortar shells were right in there. One direct hit was scored on the breech of a 75 millimeter gun just as she spit another shell of lead balls. The crew could be seen blown into the air.

“Our explosive shells hit one of the Jap ammunition dumps, and the entire hill seemed to explode as fire raged through the camouflage and grass quarters, exploding more ammunition. Sergeant Nicksich yelled with pride and joy.

“Orders were issued to the guerillas to attack Mickey Mouse Hill while the mortar barrage continued. As the fighting men approached the position, the mortars ceased fire, and the guerillas came under small arms fire. The troops did not take cover, nor did they advance; they just stood at the base of the hill excitedly discussing the situation, with their straw hats and colorful clothing giving their position away. The advance had stopped. The Japs were frantic and fired wildly with little effect It was the opportune time to attack….

“As we left our observation post, a second 75 millimeter gun began firing; this was the first time that this gun had fired that day. We made a mad rush for the base of the hill. The gunner seemed to be tracking our small party because the shells were bursting to our rear. We dived into a ditch as a volley of canister came up through the brush toward us. A civilian, who was carrying my pack, was not as lucky as we; he was hit in the chest and died on the spot. From the ditch we could see that our observation post on the hill was receiving a terrific pounding point-blank; both from high explosive and canister shells.

“Our guerilla troops could not be located; they had disappeared in the brush. The exact location of the second 75 millimeter gun could not be determined; so we decided to get the hell out of there….”

They found their observation post plowed-up by shell explosions. Sergeant Nicksich and his aides crawled out of a stream bed where they had lain in water, only their faces showing.

“Anybody hurt?” the major asked.

Nicksich counted noses. “No,” he grinned.

They prowled up a hillside and established a new observation post. They mounted the mortars and brought the second hostile field piece under fire. Scouts searched the countryside to corral the panicky guerillas.

At nightfall the guerillas reassembled. They seemed a downcast, disillusioned lot. “Why not give these babies a pep talk?” Nicksich suggested. “Cheer up the gallant chargers.”

Major Dickerson made a speech. Sergeant Nicksich made a speech. Then the guerilla officers made speeches. The guerillas replied with fierce mumbling. They made the sign of cutting throats. They waved their ancient rifles. However, one native officer and his two squads had not joined the meeting. He and some of his men had malaria, and they insisted that they were too sick to fight.

Sentinels were posted. All others stretched out to sleep on the gravel of a stream bed. The night was clear and brilliant with stars. But an hour before midnight everybody was awakened by the bursts of 75 millimeter shells. The Japanese on Mickey Mouse Hill were shelling the adjoining slopes and beaches at random. The scattered cannonade stopped promptly at midnight, and the remainder of the night passed undisturbed.

At 7 A.M., on March 2, Major Dickerson deployed his motley force for the attack. The mortarmen surrendered their carbines to the guerillas. “That,” reported Major Dickerson, “gave them great confidence and put them in a happy frame of mind.”

Nicksich crawled toward the Japanese positions to find a spot from which he could direct the fire of his mortars. He halted when he heard the chatter of Jap voices, then withdrew to a nearby knoll and relayed his fire orders.

The first shells destroyed the camouflage and brought the gun into full view. Soon high explosive projectiles struck home. Ammunition fires blazed. The guerillas spread out in skirmish lines surrounding the base of Mickey Mouse Hill.

At 11 A.M. Nicksich dispatched two colored smoke shells. They were the signal that the barrage had ended. This time the guerillas charged in true infantry style. By 11:30 they tangled with survivors on the crest and cut them down.

“While mopping up,” reported Major Dickerson, “there was a snappy little fire fight when two guerilla patrols clashed; however, it made them wiser soldiers.”

Among the Japanese equipment captured on Verde Island were three field guns, more than one thousand rounds of artillery ammunition, five hundred hand grenades, one hundred thousand rounds of rifle and machine gun ammunition, mines, rifles, bayonets, pigs, chickens, flour, sugar, rice and sake. The captured armament was distributed among the guerillas. The captured field guns proved to be of French design, American made. Eighty-two Japanese were killed on Verde.

During the early months of 1945, other raiding parties of the Division invaded and seized other islands in the seas adjoining Mindoro.

Sergeant Ernest E. Payne of Takamah, Nebraska, led a patrol to Culian Island.

On March 3 a five-man patrol led by Lieutenant James Jarret of Cutbert, Georgia, and by Sergeant Dave Boland of Portland, Oregon, secretly landed on Simara Island in the Sibuyan Sea. Their mission was to ferret out the secrets of the Jap force on Simara in preparation of an American assault. They prowled about the island for two days, counting Japanese and noting the disposition of their strength.

A Nineteenth Infantry Regiment task force invaded Simara at dawn, March 13. By March 17 the island was secured. The Japanese garrison sought refuge on a hilltop. The liberation task force surrounded the hill at dusk, and dug in for the night at its base. But in the darkness the Japs harassed the besiegers with fire from four machine guns and with scores of grenades.

The riflemen did not like it. “If we do have to sleep in grenade range,” they agreed, ‘let’s sleep it out on the hilltop, not on the bottom.”

Through the moonlit night they stormed the hill. One hundred and one Japs were killed on Simara. Twenty-one others committed hara-kiri by grenade.

The invading task force lost ten soldiers killed in action, and seventeen were wounded.

Simultaneous with the seizure of Simara, a rifle company commanded by Captain Dallas Dick, reinforced by one company of guerillas, invaded the island of Romblon.

Deep green and wildly picturesque Romblon had become a refuge for scattered Japanese remnants from other islands. To keep their presence on the isle a secret, the Japs had burned all native craft and decreed death by bayonet to all islanders caught in the attempt to flee. Already they had bayoneted some seventy civilians.

The Division’s task force landed stealthily during a torrential night rain. It traversed the black hills and valleys in a forced march, occupied the heights surrounding Romblon Town at dawn. Sudden machine gun and mortar fire caught the Japs at breakfast. Thirty were killed fleeing from their stolen houses. The survivors fled to the jungle-clad hills. Six weeks of arduous patrol pursuit followed.

One hundred and forty-nine Japanese soldiers died on Romblon.

Eighteen soldiers of the liberation force were killed in action.

Tablas, Carabao and Sibuyan Islands were freed in swift succession.

Two companies of the Division’s riflemen were flown to Mindanao to seize an airfield in advance of American landings near Zamboanga. Commanded by Major Roy Marcy of Walla Walla, Washington, they landed at Dipolog, deep in Jap country, and occupied the field. It was used by Navy Corsair planes supporting the scheduled amphibious assault.[1] These airborne infantrymen were the first American soldiers to invade Mindanao. Their skirmishes took them through country inhabited by head hunting savages. Poisoned arrows, crocodiles, monkeys and boa constrictors are among the souvenirs they collected on their way.

And then there was Lubang….

Look at Lubang. It is twenty-five miles long and nine miles wide. It lies plumb at the head of Verde Island Passage between Mindoro and Luzon. Control of Lubang meant control of the shortest shipping route between the Sulu and the South China Seas, the shortest route from San Francisco to Manila. It is what generals call a “strategic” isle. Also, it had two airfields and a radio station.

To Lieutenant Thomas R. Campbell, an ex-salesman from the White Bear Lake country of Minnesota, fell the task of reconnoitering Lubang. Colonel W. J. Verbeck of the Twenty-First Infantry Regiment considered him the right man for the job. Short, chunky, and afraid of nothing, Campbell agreed.

What did they know of Lubang Island? They knew what their map told them: Tropical rain forest surrounding central mountains some 2,000 feet high; a series of deep inlets on the island’s northern shore with the town of Lubang near its tip, and Port Tilic roughly seven miles to the east; rice fields spreading inland to the jungle-matted slopes. There would be no rain, but a bright moon in a clear sky.

The planners also knew that an enemy force held Lubang. But the strength and location of the foe — Campbell’s mission was to find that out.

He set out in a power boat a week before the scheduled assault. Three infantrymen and two native scouts were his companions. They carried light weapons, food, a radio. Mindoro’s Cape Calavite fell astern. The sea was calm. A night wind helped to subdue the purr of the patrol craft’s engines.

The blacked-out boat slipped into Tagbac Cove, not far from Lubang town. Under the stars the shore loomed black. Crouched low on a rubber raft and dipping their paddles with care, the six men made their way toward the beach.

No trouble disturbed the stillness of the night. The invaders knew the hazard of moving about in the darkness of a hostile shore. A cough, a slipping foot might mean disaster.

The silhouettes of palms stood sharp against the early morning light when the patrol approached some native huts.

The Filipinos showed terror and amazement at the sight of Americans on their flimsy thresholds. More than one of their people had lost his life under a saber for words or deeds which had displeased the Japanese.

Would the people of Lubang help the Americans to discover the secrets of the Japanese? The Filipinos were not sure. They were farmers, fishermen — not conspirators. They did not make this war and they wanted none of it. To them, the chief difference between Japanese and Americans was that the Japs stole food while the Americans brought along their own.

“No fear,” Campbell assured them. “Americans have taken Manila. Americans have punched into Bataan.”— Aye, men from his own division, the battling Twenty-Fourth.

Manila? Bataan?

It was wise to side with the winner. Slow smiles crept into the tawny faces. “But do you speak truth?” “Absolute truth,” said the man from Minnesota.

Some of the people of Lubang would help. They would be guides. They would tell the inquisitive lieutenant what they knew about the Japs.

The day was laden with busyness and stealth. Native scouts guided the patrol past enemy detachments. The Americans reconnoitered the island’s airfields, studied strongholds, landing beaches, routes of approach. No day of fishing on White Bear Lake could have yielded a richer harvest than Campbell’s secret exploration of Lubang. At times they heard the enemy’s footfalls and chatter. Then patrol and guides would melt into the undergrowth and breathe silently until the enemy passed by.

Again night covered Lubang. The Americans returned to the beach. They must rest. But where?

A dusky patriarch grinned, “Come with me.”

Follow him? Safe enough, Campbell decided. The fellow did not act like a “Quisling.” The old Filipino led them to an over grown gully at the edge of a garden patch. It was a perfect hideout.

In this secret draw, the guide explained, his people had hidden their young women whenever sake-happy Japs came searching for girls and loot.

Next morning a guerilla volunteered the information that a lone Jap soldier lived with civilians in a hut not far away.

“Are those people friendly with the Nips?”

No — but what could they do if a Jap chose to camp under their roof?

Campbell knew of plenty they could do. For instance, they could entice the Jap to a covered spot near the gully where they were wont to hide their women. How? Let the girl he was after give the scoundrel a smile and say, “Come.”

It was a thunderstruck Jap who saw Americans break out of the bushes. The girl laughed, and vanished. Campbell’s men secured the enemy and tied his arms. A job of questioning followed.

Later that day they left their prisoner to a bolo-knife guard. Circling the populated valleys, they penetrated into the hill country beyond, exploring mountain trails the enemy might use in his attempt to escape when the assault force would hit Lubang.

Their second night on the island again found Campbell’s patrol crouched at the silent beach. It was time to leave. Some whisper of their foray had come to enemy ears. They uncovered their rubber raft and pulled out through phosphorescent darkness to the patrol boat hovering offshore. And none too soon. Japanese combat groups scoured the countryside for the spy party soon after its departure.

Two days later Raider Campbell returned. This time he landed near Port Tilic, the spot he had chosen for the attack which was to put the Stars and Stripes over Lubang.

From vantage points in the undergrowth he observed the en emy garrison, counted its strength and weapons.

“Look at the stinkers swipe chickens out of a kampong,” Campbell growled. The Japs had a chicken picnic. The Minnesotan was tempted to kill the cooks and take the chicken. But he lay still.

Through forty-eight hours the Americans clung to their posts. They ate cold beans, smuggled water from a spring frequented by Japanese, fought off mosquitoes and the most persistent flies in the world.

Campbell knew all he needed to know. There was a brief con ference in a clump of kunai grass not far from the beach.

“Next time we come,” said Campbell to the native headman, “it’s the goods. Have patriots ready to lead us over the mountains.”

The headman nodded.

“You shall have horses,” he announced.

“Horses?”

“Horses to carry you over the mountains.”

Campbell grunted.

Once more he departed by rubber raft, boarded the power boat lurking in the moonlit offing.

Upon the information he brought back to Colonel Verbeck the plan for the assault was built.

Thirty-six hours before the time of the attack, Raider Camp bell made his third incursion into Lubang. With him went a combat patrol of fourteen hand-picked infantrymen, armed with submachine guns, carbines and Garands.

Two lights glowed from the beach: the guerilla signal that it was safe to land. A ripe moon had risen over the dark ridges, and there was the saturnine mutter of the surf. Wading ashore Camp bell was confronted by a lean youth with curved knives at his belt and hair covering his ears in black confusion.

“Christ,” said Campbell, “Who are you?”

“We are ready,” whispered the boy, his belly-muscles rippling.

“Fine,” said Campbell, and then spontaneously, “Why don’t you get a haircut?”

“The horses, too, are ready,” said the guerilla. “I and my friends have sworn not to cut hair until the last Japanese in the islands is dead.”

“Good enough,” growled the American. ‘We have brought rifles for your friends.”

“How many?”

“Forty.”

The patriot was pleased. Soon they moved inland. Through the rest of the night and all the following day they remained in a cluster of bamboo huts at the edge of a swamp. Japs passed nearby, singly, more often in groups. The croaking of bullfrogs and the chirping of cicadas filled the air and bats flew silently about the huts. And during the day not more was to be seen than a few women beating rice in wooden mortars, children playing, and an old man carving a paddle for his canoe.

All the same, Campbell was busy. Runners were dispatched to Port Tilic to warn the inhabitants to filter into the hills after sundown. Scouts went into Lubang Town to spy and mark all houses occupied by Japanese. The plan was simple: The invasion would hit Tilic Harbor. Campbell’s patrol would create a diver sion in Lubang Town to draw the enemy from the spot chosen for the landing. Fine— but why not go into Lubang this very night? Kill the Japs, take over, and then tell the colonel, “Here is your blasted island.” What was wrong with that?

His men nodded their appreciation. Campbell called for the horses. He stared at the mounts. “Horses!” In the dark they looked to him like a crossbreed between llamas and razorbacks.

Fourteen foot-slogging infantrymen mounted their “razorback” steeds. Afoot, they grumbled, they could make better time than any island “horse” could carry them. But if the lieutenant wanted to ride… Hell, what Campbell could do, they could do as well.

Across the mountains of Lubang, in single file, rode the first horse-infantry of the Pacific war. Out in front was the long haired guide, his bolo knives augmented by a potent Garand. Close at his heels rode chunky Campbell. The guerillas moved noiselessly through the flanking jungle. Through the stifling for est gloom the rear horseman fathomed the trail less by sight than by the smell of the ponies trudging in the vanguard.

At 9:30 P.M. the patrol emerged in the rice fields. At 10 p.m. they reached the outskirts of Lubang town. Campbell signaled, “Halt.”

The dogfaces sighed. Their bodies ached from their unwonted ride. They slipped from their mounts and felt better.

Hugging their Garands, the guerillas fanned out into the dusty streets. They surrounded each house which harbored Japs. The infantry followed.

At 10:45 pandemonium engulfed Lubang Town.

A sentry shouted, heaved a grenade, was killed by a shot fired at arm’s length. Guerillas pounced into the huts. The night rang with a macabre crescendo of howls. Japs darted from doorways, jumped from windows, crawled beneath the houses, dashed wildly down the moonlit streets. Grenades tossed through windows erupted through palm-thatched roofs. There was the tearing sound of submachine guns spouting and there was the dry bark of the Garands. The guerilla leader and his hirsute friends worked with butts and jungle knives. A Jap screamed under a blade that cut his throat. A few fought back. Campbell kept moving, directing his men. Three times grenades burst plumb on spots where he had been standing seconds before.

At 11 all resistance ceased in Lubang Town. The enemy dead sprawled in the streets, in the huts, under the huts. The patrol moved out.

“Back to the ponies,” was all that Campbell said.

In silence they rode through the night toward Port Tilic. A red glow hung in the sky. They arrived above Port Tilic at 2:30 A.M., ready to attack. But the guerillas, as usual, had disappeared. “Damn,” said Campbell. “Might as well take it easy.” They curled up in the brush and slept. When they awoke it was dawn. Warships dotted the horizon. A naval cannonade set Tilic Harbor afire. When the shelling stopped, Campbell said, “Let’s move in.”

They combed the town of Tilic before the task force hit the shore.

Weeks of bitter mopping-up fatigue followed. A battle patrol led by Lieutenant Bob Carmody of Pittsburgh skirted the island in canoes, then struck inland and blocked a number of mountain trails. A score of fleeing Japs died in the ambush.

Another patrol discovered sixteen Japanese “Q-boats” tied to a ramshackle wharf. Each of the suicide launches had been booby-trapped with torpedoes. But the traps were disarmed, and infantrymen used the launches to exterminate enemy groups holding out in coastal villages which could not be reached by overland trails.

One patrol of four was lost in the mountains of Lubang. A rescue patrol of three set out to find them. Colonel Verbeck gave way to his flair for adventure and made himself the leader of this patrol. Roaming the hills they encountered a tough bunch of Japanese. One man of the rescue party was shot to death. A Jap bullet pierced the colonel’s shoulder. With a fine smile, Verbeck asked the combat reporter covering the operation not to write a story about his wound. (“What will folks think of me when they hear that a colonel leads a three-man patrol, hey?”) The lost patrol of four was found days later; all four soldiers had been killed and mutilated beyond recognition.

Meanwhile, a cowboy from Wyoming named Raymond Lund, rounded up six native horses to carry telephone wiring equipment across Lubang Island. Lund had trouble. At times he carried the horses’ loads. At other times he was chased by his angered steeds. Crossing mountain rivers, he was forced to unhitch all equipment and to lug it across the river himself in hundred pound loads. He then returned to lead each horse through the current. When Lund emerged on the other side of Lubang, he came alone and afoot. He had laid forty-three miles of wire in three days. And all of his horses had died on the way.

Eight Americans lost their lives on Lubang; eighteen were wounded. Two hundred and twenty-seven enemy corpses were counted on the island. Six Japs were seized alive.

(Continue to Chapter 18: Return to Bataan)

___________________________________________________

[1] The American landings at Zamboanga were effected by the Forty-First Infantry Division two days after the Dipolog airfield had been seized by two companies of the Twenty-First Infantry Regiment.

Great write-up! Soldiers not specifically trained for unconventional/guerilla warfare, doing UW warfare. Thanks for the pick me up!