Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 21 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 20: Thunder to Davao)

Sergeant Robert L. Roberts of Newark, New Jersey: Somewhere north of Davao we came to a shack. At least it looked like one. We pumped it full of bullets just to make sure. It turned out to be a fire-spitting pillbox and we hit the ground fast. Two men in my squad were hit. We burned out the Japs. Five or six were running away, flames curling from their backs. They carried American rifles they’d captured in Bataan — years ago.

Private First Class Clyde Burton of Eubank, Kentucky: I was sleeping at night in my foxhole outside of Davao. My buddy stood guard. Suddenly he nudged me. “Slant-eyes a’comin’,” he said. I rubbed my eyes and my feet hurt from hundreds of miles of walking and then I realized what was up. Hand grenades were popping all over the place, both Jap and ours. Everybody on the perimeter was blazing away and bullets were flying in on us from all directions. We heard the Japs howl like mad monkeys as they charged us with bayonets. Two of them were coming for me. I let ’em have it. One fell dead, the other plopped into my foxhole still a little bit alive.

Private Joe Stewart of Courtney, Missouri: I was sitting at the edge of the road, cooling my feet in a ditch. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw eight Japs march single file right down the middle of the road. They were camouflaged and they looked just like a row of bushes moving down the road. It was a beautiful sight. I lined up the sights of my automatic rifle and squeezed the trigger. The first two fell. Then my B.A.R. jammed. I jerked the bolt and fired at the others who were running into the bushes. The B.A.R. jammed again. It was clogged with mud. I was so angry that I wanted to throw my gun at them. Well, I sat there cleaning the thing, when two of the Japs came back to drag the two dead Japs off the road. I got them too.

Private Ralph Cole of Mount Pleasant, Michigan: Night attack. The Japs came in like a laughing pack of hyenas, bayonets in front and tossing grenades. Everything was in an uproar, shrapnel flying, bullets whizzing, tracers zipping like lightning through the jungle. And suddenly a Jap jumped into my fox hole. My machete was sticking in the ground nearby. I grabbed it and hacked away at the Jap. I hacked his arm off with one good swipe. He backed away and I shot him a couple of times. Still he kept coming. He was the hardest dying character I’ve ever met. Later when I tried to get some sleep he woke me up with his moaning. So I put him out of his misery with two more shots. I noticed then that I was bleeding, too. Shrapnel.

Sergeant Freeman Smith of Norway, Maine: I was moving up a narrow trail about ten yards behind my scouts when I noticed two Japs lying in the bushes about five feet off the trail. At first I thought they were dead. But Japs have a trick of playing dead, letting you pass, then throw dynamite at you from the rear. I hunted around for a pebble to throw at them to make sure. No sense in wasting bullets on dead Japs. But before I could find a pebble I saw one of the Nips reach up and brush a centipede off his forehead. That’s all I needed to make up my mind.

Lieutenant Colonel Harold E. Liebe of Tacoma, Washington; Field Artillery: In the fight for an entrance into Davao infantrymen had established a bridgehead at the Davao River. From high in the hills Japs shelled our troops with a six-inch naval gun. Casualties were heavy. My men decided to do something about it. They manhandled a 105 millimeter howitzer across the river and up a hill on nothing but their muscles and guts. From then on it was a point blank duel. It was firing by “bore-sighting”— that is, you look down the barrel of your howitzer until it is on the target. After an hour of dueling we knocked out the competition.

Private Joseph Turner of Warren, Ohio: My job is mine clearing. I was walking along with my mine-clearing crew when suddenly a 250-pound aerial bomb dropped in front of us out of a tree. The Japs had rigged up a block and tackle in a tree along the road, hoisted the bomb to the top, and then waited a safe distance away with the end of the rope that held up the bomb. Lucky for us, that bomb did not explode. Six Japs pulled the rope, bouncing the bomb around the ground until one of our men shot through the rope with his Tommy gun. At another time we had found a bomb in the road and we had lit a fuse to blow it up. Some Japs in ambush started firing, hoping to keep us pinned down until the bomb exploded on us. They were not successful. We were not always so lucky. On the edge of Davao a bomb disposal squad worked to disarm a mine when the mine exploded. Nothing was left of the squad except a blackish smear on the tree trunks.

On May 2 a Division spearhead commanded by Colonel Clifford punched into Davao. The first problem of the attack was the crossing of the broad Davao River. Clifford solved it by a bold ruse. Division artillery showered a barrage on the logical site for the river crossing. As soon as this barrage lifted, a Japanese counter barrage upon the same area commenced. The enemy commanders were convinced that the major attempt to force the water barrier would be made at this point. But Clifford’s riflemen crossed the river over a hastily constructed foot bridge several hundred yards upstream. The attack groups crossed the precarious structure at a fast run. They swarmed into Davao City before the Japanese realized their mistake.

Though the city of Davao was stormed, the rataplan of machine guns, the roar of bombs, the screaming of rockets, the thunder of artillery lashed the countryside around Davao for months. The Japs of Davao fought with arrogance, and with a complete contempt for death. For months to come the men of the Twenty-Fourth Infantry Division were locked in the hardest, bitterest, most exhausting battle of their ten island campaigns. “As bad as Breakneck Ridge,” they said. “And bigger.”

Possession of Davao City and of Mindanao Island was less a matter of strategic importance than a matter of American prestige. Already with the fall of Leyte, Mindoro and Luzon the Japanese in Mindanao were hopelessly cut off from their homeland. Their planes had been destroyed and their ships had been sunk; and their naval and aviation personnel fought as infantry. But American “face,” much damaged by Nippon since 1941, had to be built up anew and stronger by the violent extermination of Jap forces who already had been castrated in a larger military sense. The dogfaces who fought and won this “battle of prestige” fought it without enthusiasm, but with a sullen and melancholy hatred. More than ten thousand Japanese died around Davao at the hands of Twenty-Fourth Division men. Among its own the Division counted two thousand, seven hundred soldiers wounded or missing or killed in the Davao fighting. Since the now distant date of the Division’s thrusts into New Guinea and Leyte, more than 25,000 Japanese fighting men had died in its path. But the blood price our fighting team has paid for its share in guarding America’s life and happiness, measured in terms of maimed and killed comrades, stands very near the six thousand mark — six thousand out of an organization roughly 15,000 strong. In the ever two-sided agony of combat they died, in this last campaign of the island war, in the sweltering abaca fields, on the blasted slopes of Hill 550, on brush-covered ridges, in the savage gorges of the Talomo River, in the hostile Mandog mountains and on the fringes of never explored wilderness which surrounds Mount Apo with saturnine and inscrutable green.

To the foot soldiers fighting in Davao Province, the word abaca was synonymous with hell. Abaca is the plant from which Manila hemp is made. Countless acres around Davao are covered with these thick-stemmed plants, fifteen to twenty feet high; the plants grow as closely together as sugar cane, and their long, lush, green leaves are interwoven in a welter of green so dense that a strong man must fight with the whole weight of his body for each foot of progress through this ocean of verdure. In the abaca fields visibility was rarely more than ten feet. No breeze ever reached through the gloomy expanse of green, and more men — American and Japanese — fell prostrate from the overpowering heat than from bullets. The common way for scouts to locate an enemy position in abaca fighting was to advance until they received machine gun fire at a range of three to five yards. One rifle platoon lost fourteen scouts in the course of the “abaca campaign.” The intricate Japanese abaca entrenchments were supported and protected by the largest concentration of naval and field artillery ever encountered by the Twenty-Fourth Division. One hundred and ninety pieces of Japanese artillery were captured and destroyed in the Battle of Davao.

The assault bridge across the Davao River was the handiwork of a sergeant of combat engineers. There was an old bridge, but a forty-foot gap had been blown out of its middle, and the bridge ends had been mined. Clifford thought that he would have to force the crossing into Davao in assault boats. But forward strode Sergeant Alfred A. Sousa of Honolulu, Hawaii.

“Give me four hours and I’ll fix that bridge,” he said.

The officers gave the sergeant carte blanche. Sousa studied the far end of the bridge. His trained eyes spotted five mines and a bangalore torpedo under a case of blasting powder. Strings for detonating these charges converged on a masked foxhole a hundred feet from the river’s edge.

Under the covering muzzles of a rifle squad the engineer plunged into the river. It took him forty-five minutes to buffet his way to the hostile bank. Stealthily he cut the converging strings, aware that at any moment a sniper’s bullet or a mine explosion might put his enterprise to an irrevocable end.

The mines were disarmed.

In broad daylight, with only his knife as a weapon, Sousa scouted the enemy side of the river. He was the first American soldier to set foot into Davao since 1942.

His reconnaissance completed, Sousa again bucked the current and summoned his men to the job at hand. Infantry waited. After a few hours and a truckload of sweat a crazy quilt bridge of ladders, tree trunks, blasted timbers and ropes spanned the Davao River.

A rifle platoon led by Lieutenant Clifton L. Ferguson of Indianapolis, Indiana, was first to storm into the city of Davao. Crossing the river with the spearhead were Colonel Clifford and General Kenneth F. Cramer, the assistant Division commander.

“It looked like a cinch,” said burly Cramer. “But after a few minutes it was worse than anything Leyte ever had. Artillery seemed to be firing at us from point blank range and mortar shells were falling all around. Guesses are never good enough. You never know really what’s going to happen until you go in there to get shot at. That’s the only reliable source of information.”

Fanning out from Davao, every battalion of every regiment lay in continuous battle.

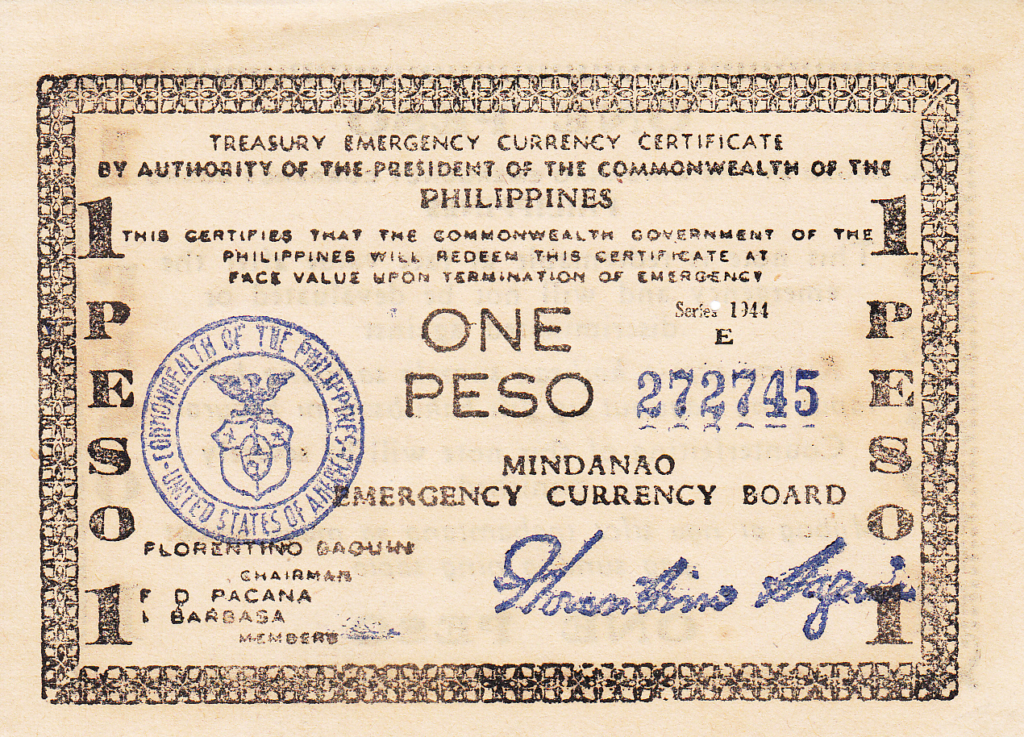

Davao was a leveled city. Only a few shells of buildings were standing. Much of the town had been razed by American bombs. But the Japanese had dismantled and carried off into the hills more than one thousand of the best houses. With the vanished buildings went Davao’s 19,000 Japanese civilians. The Filipino population, too, had fled. When the Division’s Civil Affairs Officer[1] walked into Davao (with a mimeographed list of ceiling prices in one pocket, 35,000 victory pesos in another) to take over the city’s administration, he found that of the town’s original 90,000 residents barely one hundred were present to welcome the “liberators.” These remnants lived in an agglomeration of rag-tag huts built out of wreckage in an atmosphere of graves, corpses, ruins and a weird congress of skeletons in what once had been Davao Penal Colony. Looking over his domain, the administrator muttered, “Well, there seems to be almost nobody around to be liberated.” A frail native woman, Madam Baldomera Sexon, who was the director of Davao’s Mission Hospital, told the officer that more than 25,000 Filipino civilians in Davao had died of malaria, typhus and execution at the hands of the Japanese.

Advance patrols were ordered to look for a secret city which the Japs had built out of the stolen homes of Davao somewhere in unexplored territory. Guerilla scouts filtering through enemy lines reported that the Japanese were training thousands of their women for combat. All Japanese women between twenty and forty were ordered to wear trousers, cut short their hair, and after that they were trained to fight with grenades and bamboo spears. General Eichelberger, the Eighth Army commander, broadcast a warning that “If these Japanese civilians do not surrender, we intend to kill them as we find them.”[2]

American planes dropped thousands of leaflets over Japanese lines. The leaflets asked Japanese civilians to return to Davao: “We do not wish to kill old men, women and children.” Safe conduct, food and medical relief were promised.

Not one Jap civilian surrendered.

But Filipinos came in big, terrified hordes. They came in groups of many thousands, guided by steel-helmeted infantry patrols. Their march back to Davao resembled a migration of bedraggled ants. Men were ragged and starved and broken down by forced labor. For months the Japanese had compelled them to dig trenches and tunnel fortifications. Women with babies sucking wilted breasts staggered under the weight of heavy head loads. Children limped on swollen feet. Some had been wounded while crossing artillery impact zones. There were few smiles. And intermingled with the returning civilians came the spies and the people of the underworld.

In the prostrate city two industries flourished: spying and prostitution. Venereal disease was rampant after three years of Japanese occupation. A Jap soldier with syphilis or gonorrhea knew that he would be beaten by his officers; therefore he hid his sickness, and escaped cure. Nearly half of Davao’s young women were diseased. Two cigarettes or a piece of soap would buy a girl for a night.

General Woodruff promptly declared Davao “off-limits” for troops not engaged in Jap-killing or municipal administration.

Heavy Japanese artillery pounded Davao for days. A crowded field hospital and a command post suffered direct hits.

During the second night following the capture of Davao the Japanese launched five successive Banzai charges. Japs carrying grenades, rifles, machine guns, and land mines strapped to their bellies raided the center of the town. Many of the mines were exploded by American bullets. The explosions threw Japanese bodies over the mounds of rubble. A head sailed into the command post of Lieutenant William Paul of Long Beach, California. An arm and two feet dropped into the command post of Captain Victor Bazzinotti of Cadogan, Pennsylvania.

Japanese gunfire destroyed six American tanks.

Japanese fighting men held grimly to their defenses surrounding Davao. Months of ceaseless air bombing and strafing, ceaseless artillery bombardment, ceaseless infantry attacks were required to dislodge them.

Day after day a devouring heat poured from sky and earth. Heat prostrations took a grim daily toll. Some companies counted only seventy men fit for battle. The nights often brought heavy rains and four, five, six wild-beast counterattacks in the dark. Verbeck’s Twenty-First Regimental Combat Team seized Mintal and fought desperately for Libby Drome, the largest of Davao’s airfields, then pounded into the wilderness north of 10,000-foot Mount Apo. Clifford’s Nineteenth Regiment slugged northward along the shores of Davao Gulf, captured Sasa Airdrome, Samal Island, and the towns of Panacan, Tibunko and Bunawan. The Thirty-Fourth Regiment, meanwhile, struck along the Talomo River Valley toward the bastions of Ula and Tamogan. Thus the Division’s battle teams fought simultaneously on three fronts, striking the enemy’s main line of resistance in the center and from both flanks.

The Division’s field artillery thundered day and night. Fire bombs sown from planes set wide areas of abaca afire. The Japanese again resorted to the tragically futile expedient of concentrating masses of Filipinos around their positions as hostages against American bombardments. Ambushes infested all roads between dark and dawn; along the Division’s 150-mile supply line no road was safe at any time. Davao City as well as the Division command post came under hostile artillery fire. A Japanese canoe patrol blew up and sank one of the first American supply ships to enter Davao Gulf.

Each night, on each perimeter, Japanese were caught in the attempt to sneak through the foxhole lines with dynamite strapped to their bodies.

In close-quarter night battle Jap soldiers were beaten to death with fists, with rifle butts, with shovels. One officer stood in conference in his battalion command post in a banana grove. His back was resting against one of the bushes. A Japanese materialized from nowhere. He thrust his bayonet through a banana stalk and impaled the officer.

A Japanese raiding party landed in a log canoe near the command post of the Division. They penetrated the command post under cover of darkness, scattering mines.

One weary sergeant commented:

“People visualize pillboxes as little round things that stick up and are visible like the concrete pillboxes in Normandy. But these pillboxes here follow the contour of the ground so that there is absolutely no sign of their presence except the two-inch- wide firing slits. You could walk by one each day for a year and never know it was there unless someone shot at you. The fields and woods are full of Japs. You cut through them with machine guns and flame-throwers and they close in right behind you.”

The Division cemetery, well behind the lines, was growing in leaps and bounds. Burial parties were frequently forced to fight their way through to put the dead to rest.

First Lieutenant John A. Schwengels of Bellit, Wisconsin: I am a platoon commander in the Division’s Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop. We operate with half-tracks, jeeps and armored cars. Our troop is a spy-slug-and-run outfit, the feelers of the foot-slogging infantry.

My platoon was the first American force to drive into the Dig Lioanan airstrip north of Davao. There were four runways. The roads around them were mined and the Japs had planted innumerable booby traps. My half-track spun around a mine, almost scraping the detonator. For a second my hair stood on end. Then we bounced onto the air field and stopped. Scattered along the strip were some two hundred big aerial bombs. So we dismounted and did some crawling. We crawled on our bellies from bomb to bomb and cut the detonation wires. In between we put a flock of snipers to flight.

After that we reconnoitered the fringes. The tall grass on both sides of the road was quivering with Japs. Every once in a while we stopped and raked the whole business with machine guns. We had two half-tracks and six jeeps, a machine gun on each.

There was one Jap who wouldn’t quit tugging on a red cord. We shot the Jap and we cut the cord and then we found that it led to two 500-pound bombs. A little way further, twenty Japs attacked with grenades and mines. Our machine guns sang their song of death.

Next day we were cut off from our infantry by a strong Jap force. We threw some 150 mortar shells in their direction. The shells set off some buried bombs, and when we finally broke through we had to buck through big craters in the road.

The same day we captured a Jap mountain gun. But the Japs forced their way back to the gun and blew it up with dynamite. Then we pulled into an area studded with Jap barracks. The infantry behind us was halted by a hostile barrage and we fell back and hugged the ground and called for our own artillery fire. Our cannoneers dropped a hundred howitzer shells into the Japs while we lay flat and watched. Earth and junk flew all over us. When the barrage stopped, we pushed on again.

Next came fire from a pillbox. We knocked it out. Then came fire from a stream bed. We killed thirty Japs and overran the rest.

After that we ran into a dead-end of heavy fire. The lead half track tried to back away, but stalled. I jumped out and one of my boys yelled “Look out!” I whirled and faced a Jap who was charging me with a bayonet. I ripped him with my Tommy gun until his guts spilled on the road.

We fought six days for this one airfield, one of seven around Davao, keeping alive by firing first.

Sleepless, sweating, begrimed Captain Sidney B. Luria, a battalion surgeon, patched up 262 battle casualties in five days and five nights of unremitting labor. To his little surgeon’s tent were carried men with bullet punctures, with smashed arms or legs, with broken skulls, with bodies ripped by shell fragments, with nerves jangled from the constant pounding of high explosive. “Doc” Luria used an average of two bottles of plasma for each man. He worked under artillery barrages, mortar bursts, and during night attacks — by flashlight, crouched under a poncho in foxhole muck. Not one of his patients died.

An exploding bangalore torpedo supplied a thunderous overtone to the singing of Corporal Robert Lussier of Woonsocket, Rhode Island. It also bounced his truck like a rubber ball.

Lussier drove his supply truck along a dark, abaca-flanked road. The stars were out and the Frenchman from New England was singing “I’ll Walk Alone.” He saw a round object, three inches in diameter and about three feet long slide out into the road from the hemp thicket; but busy with his singing he thought nothing about it until the torpedo exploded and bounced his truck.

Lussier roared. He grabbed his carbine and leaped out of the truck. But the Jap had disappeared in the abaca.

Lussier peered under his truck. His sensing hands found that fragments from the torpedo had punctured the heavy housing of the differential before tearing through the floor of the vehicle.

He sat beneath his truck and again he sang “I’ll Walk Alone,” his carbine ready, hoping that the Jap would try again.

He plugged the holes with sticks to keep the oil from running .out and then he pulled away from there.

The platoon of Sergeant William Braswell of Jacksonville, Florida, assaulted a barricade of pillboxes north of Davao. A Japanese “woodpecker” (light machine gun) rippled from a hidden foxhole on the right. The burst caught one of the scouts, through the shoulder. Braswell heard the scout’s outcry, then saw him fall. The wounded soldier was struggling to roll himself to the cover of a log, but could not make it alone. Braswell sprang to the wounded man’s side. Machine gun slugs cut the foliage above their heads and the sergeant saw that his scout’s face had suddenly turned into a yellowish gray and that he was frozen with fear. Then Braswell saw what was the matter.

A Japanese grenade had plopped on the scout’s back and had lodged between the fallen man’s shoulder blades.

The sergeant from Florida had led his platoon through many battles. He had seen death in every conceivable form and at close range. Each time one of his men had died it was as if he, Bill Braswell, had suffered death himself. He lunged forward to toss away the grenade and then it exploded. It killed the wounded scout and blew off Braswell’s hand at the wrist.

Field artillery had thoroughly pounded a palm grove where Japanese soldiers had been spotted digging holes. When the shells stopped falling, Private Don Foster, a radioman from Long Beach, California, went forward to scout the impact area. He found the bodies of enemy soldiers in contortions such as only artillery bursts can produce. On the edge of a clearing crossed by a tinkling brook he saw an untouched palm-and- bamboo hut. In a patch of hibiscus in front of the hut lay the still warm body of a woman.

Don Foster cautiously circled the hut and peered inside. In the half-darkness he saw the body of another woman stretched out on the floor slats. In the hollow of her arm she held a tiny infant. A child of about three crouched in a corner of the shack and gazed at the strange soldier out of large black eyes.

Don Foster entered the hut. The second woman, he found, was dead. The infant in her arm was alive, slimy, skeleton-like and acrawl with ants. Foster radioed for help.

A medic said that the mother had died from lack of care after childbirth, and that the infant was about five days old. The older child — a girl — was starved but in good health. Six infantrymen dug a double grave while six others stood guard. They buried the young mother and the older woman. Through an eye dropper they fed the infant canned milk mixed with chlorinated water. They washed the baby and made a diaper out of first aid band ages and saved its life. Their company adopted the infant’s three- year-old sister. The 150 foster fathers called her Geraldine Irene — G.I.

During the assault on Maag Hill, Corporal Robert Melin of Visalia, California, saw two of his squad crumple in the path of Japanese machine gun fire. One yelled for help, and the other thrashed about on the steaming earth. Melin crawled forward hard beneath the bullets that were like so many shuttles weaving a pattern of death. He reached the fallen men and dragged them, first one and then the other, into the shelter of a lauan tree. He gave them morphine and bandaged their wounds and covered them with their ponchos to alleviate shock. He had finished his job, dimly aware that the fire fight was gradually moving up the sun-baked slope. He gulped a mouthful of water from his canteen when he heard a hoarse pleading from not far away.

“Oh, my leg… Oh, God… my leg.”

Corporal Melin closed his mouth and thrust his canteen back into the canteen carrier on his belt. He shook himself like a dog that has just escaped from a burning house, and out he crawled again where bullets decapitated blades of green grass. He saw a machine gun spit fire from a grassy mound and he found a soldier whose leg had been broken in three places by a mortar blast.

He gave the crying man morphine, and he gave him sulfa tablets and water. He sprinkled sulfa on the leg wounds and bandaged them. Then he crawled toward a bamboo clump to cut some splints. The wounded soldier had become quiet and his eye followed Melin to the bamboo and they followed him on his return with the freshly-cut splints. Just then the machine gun under the grassy mound again snapped bullets. Melin threw himself flat. He felt something rip through his sleeve and he heard bullets whine past beneath him during the fraction of a second which it took him to hit the ground. He landed with his head between the wounded soldier’s feet. The burst of fire had riddled the man he had come to save. With the dogged battle loyalty that does not allow of analytical thinking he dragged his dead comrade to cover of the lauan. He still clutched the bamboo splints as he raised his head and yelled toward the rear for litters.

First Sergeant Woodrow Woods of Whitesboro, Texas, spotted a Jap crouched in a hole at the base of a volcano. The Texan roared, “Get the hell out of that hole!” The Oriental obeyed. “Hands up!” the Topkick roared. The Jap stood still.

His finger on the trigger of his rifle, Woods approached to relieve his captive of some grenades which bulged in the Jap’s blouse pockets. The Texan reached, but the bulges were not grenades. The Jap was a sullen, cropped-haired young woman.

Sergeant William Duncan of Roxbury, Massachusetts, asleep in a foxhole, thought he heard some firing.

“What’s the matter?” he growled.

His foxhole companion, a boy of nineteen, whispered excitedly, “There was three Japs in the road. I shot one. Gee, Sarge, I got my first Jap.”

“Well,” he grunted, “Why in hell don’t you shoot the other two?”

A mild mannered geologist from Salt Lake City cleaned out a Jap pillbox which had killed two men of his squad. The scientist, Sergeant Rondo Birch, climbed on top of the pillbox. He tossed a grenade through the firing port. A Jap ran out. Birch brought him down with his rifle. Then he tossed a second grenade. Two more Japs popped out and ran some distance, then changed their minds and counter-attacked. Birch fought them from their own pillbox. They exchanged fire, springing forward, shooting, ducking, shouting. After fifteen minutes both were dead — one shot through the head, the other through the heart.

Sergeant Tudor Price of Lake Crystal, Minnesota, heard a noise in the night. He unleashed his machine gun. There were sounds of bodies falling in the brush, then moans, then silence. At dawn he found that he had shot a horse and two dogs.

Soon the dead horse began to smell. Tudor Price was ordered to bury it. All day he dug. Toward evening, his company commander heard him curse and growl maledictions into his foxhole. “What’s the matter, Price?” he asked.

“Sir,” answered the sergeant, “did you ever bury a horse?”

Between Talomo and the city of Davao there is a wide clearing among the thickets of abaca, scrub palm and banana. There are rows upon rows of little wooden crosses, and each cross bears an American name. And there are other rows; rows of open graves as yet unnamed. Still forms swathed in olive-drab blankets lie in the open graves. Others still lie above the ground, sprawled and twisted as they were carried from the battlefield. Bullet victims, artillery victims, grenade victims. Across the humble acre of God artillery shells pass with sibilant howls. The rumble of distant explosions drifts over the crosses and the open graves, and over nearby hills planes are bombing and strafing. A solitary figure stands poised before an open, not empty, grave. It is the figure of a stocky, fearless, unarmed man: the Division Chaplain. Major Paul J. Slavik of St. Paul’s Church of New York City is burying the four hundredth American in the Division cemetery near Davao. Except for the crew of Filipino diggers he is alone. His voice is firm and sad,…

“We praise and bless Thy glorious Name, O Lord, for the devoted sacrifice of Thy servant who has laid down his life that we might live. Into Thy holy keeping we commend his soul, and humbly pray that we, as did he, may give and never count the cost, fight and never heed the wounds, toil and never seek for rest, labor and ask for no reward save the knowledge that we will do Thy will; through Jesus Christ, our Lord. Amen.”

There is a flare-up of rifle fire in the swampy underbrush a few hundred yards off. A patrol of helmeted men with submachine guns and rifles crosses the cemetery in swift-moving single file. As they approach the rim of the thickets they fan out into a skirmish line and the crackling of rifles becomes vicious and sustained. A machine gun hammers in the bushes. The Filipino diggers scatter and seek cover. For one short second Paul Slavik is hesitant as to what he should do. But then he is again his old self, calm and strong and duty-bound.

“We commit the body of our comrade to the ground in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, looking for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.”

The machine gun in the bushes has fallen silent. The cracking of rifles is moving away into the distance. The diggers emerge from cover and assemble large-eyed under a molave tree and watch. Paul Slavik raises both arms toward the sky. Overhead the eerie wailing of artillery shells continues without interruption. Over the strange, wild countryside his voice becomes a ringing and somber appeal.

“May God the Father, who has created this body;

“May God the Son, who by His blood has redeemed this body together with the soul;

“May God the Holy Ghost, who by baptism has sanctified this body to be His temple —

“Keep these remains unto the day of the resurrection of all flesh.”

The chaplain lowers his head in a mute farewell. He addresses the silent man down there under the olive-drab blanket as if the soldier had been his son:

“The Grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the Communion of the Holy Ghost he with you forevermore. Amen.”

He makes the sign of the cross and for a moment he remains in a final, silent prayer. The diggers advance slowly.

At sunset two tough, dirty, sweat-encrusted soldiers moved out among the rows of crosses. Their helmets they carried in their hands. In his helmet each carried a flower he had dug from the edge of the jungle together with its roots and a clump of soil. They halted in front of the fresh mounds and bent low and studied the names on the crosses. Then they found the name.

“That’s Robert,” one of them muttered. “Christ, last night we had the same foxhole. He was telling me all about what he’d do when he got home again…”

The voice trailed off.

In silence the two living set aside their rifles and planted their flowers in the fresh mound. Then they stood in upright immobility and stared down at the grave as though they could see their comrade looking up at them through the tropical earth. “‘Bye, Bob,” said one. The other said nothing. They turned and grasped their rifles firmly and moved away in the twilight.

Staff Sergeant Noah W. Skinner of Richmond, Virginia: I am in charge of an anti-tank squad. Before the war I was a Professor of German at the University of Richmond. Don’t ask me why I am in the Philippines — I haven’t been able to figure it out either. Anyway, I’ve learned a few things.

I’ve often wondered why the Japs are such hardy fighters. They are made that way by their training. Brutality was beaten into them. Jap training was the most brutal in any army. Once a prisoner told me that many Japs committed hara-kiri during training just to get out of it. Jap soldiers must stand at attention while they are being slapped and kicked by their superiors. Any Jap who outranks another had the right to administer punishment at any time. After six months in the field the one-star private became a two-star private, and with promotion he earned the right to beat up the one-star privates, which he did with gusto. Mix the results of this with emperor worship and a deep love of home soil — and you have the Jap soldier.

But remove a Jap soldier from the influence of his superiors and you will often find a very scared and confused man who hates the guts of war and who goes out to get himself killed to get it over with. He is so dangerous as an individual fighter because he expects to be killed. On the other hand, his hara-kiri is less a gesture of “fanaticism” than a last protest of a man at the end of his rope. His hobbies are normal: sleeping, getting drunk, and fornication….

Since the Japanese had only few tanks, we of the anti-tank teams had to find new uses for our guns. We used them to fire “canister.” A canister is nothing more than a tin can filled with 120 steel balls. The gun blast spreads the steel balls into a scatter-gun pattern against which no Banzai charge can stand up.

My gun’s name was Betsy. Once we were on a perimeter near Mintal, west of Davao. Betsy was in position, loaded and waiting, covering the intersection of two roads. The vicinity was covered with demolished buildings, lumber, concrete and twisted sheets of corrugated iron roofing. It was one of those completely black nights. Along about 0130 I heard a faint rattling among the rubbish. My gunner and I threw grenades toward the spot. Two Jap woodpeckers opened up on us. Grenades flew back and forth. We pointed Betsy first at one woodpecker, then at the other, blasting away with canister. Then we swept the road with more canister. When canister sweeps up a road nothing that’s unarmored between the road shoulders has a chance to live.

A few minutes later we heard whispers. It was some Jap giving instructions farther up the road. After that there were three Banzai yells from scores of Japanese throats and on they came. My gun vomited steel. The Banzai collapsed. Through the rest of the night we could hear shuffling and scraping sounds of Japs dragging away their wounded. Then came dawn. With three blasts of canister I had killed eleven enemy soldiers and one officer.

Another night I had my foxhole between the trails of the gun. I was suddenly jolted by a Jap voice muttering almost into my ear. There was a glow of lightning, and there, directly over me, was the silhouette of a Jap bayonet. My carbine spoke. The Nip dropped, his steel clattering against the cannon trail.

From now on I kept alert. I soon spotted another Jap who had crawled up under the barrel of my gun with demolition charges. He was peeping around the tire when I shot him. Before he died he muttered the English words, “Crazy man.” More Japs were running in front, so I let go with canister. When I checked over the corpses next morning I found one Jap who must have been standing directly in front of the gun muzzle. He looked as if a 12-inch shell had gone through his middle.

Sergeant Fred Livingston of Boyce, Texas, took a last drag from his cigarette before he spoke to his men.

“This is the place,” he said. “You can’t see the entrance from here, but I know where it is. Don’t fire until you see that I’m there.”

With that he crawled away and up the brush-covered slope. It was a routine mission: to blow up a Jap cave. The small, camouflaged entrance of the cave opened just below the crest of a ridge facing the Talomo River.

The men crouched, waiting, their fingers resting on the triggers of their rifles. When they saw their sergeant signal from the top they opened fire.

Livingston was on his feet running. Thirty feet from the cave mouth. Then twenty. He hurled the dynamite bomb, swerved sharply and plunged back down the slope.

There was a big explosion. Then, incredible to the dirt-hugging men, another, more violent, and yet another. The hill bubbled. Flames shot from other concealed tunnels. The whole hilltop disintegrated. The men were stunned and deafened by the blasts which continued to come in split-second intervals. The concussions slammed them into the ground, lifted them into the air, slammed them down again. Smoke and dust covered the summit. Rocks, sprays of earth, smashed corpses and fragments of broken trees rained down the hillside.

The cave had not been a simple cave. It had been one exit of a labyrinth of tunnels packed full of ammunition and gasoline.

Sergeant Gerald Bouffard of Watersville, Maine, led his squad in the attack on a pillbox. The Japanese gunners fired with cool insistence. A stalemate threatened.

Bouffard told his men to cover the strongpoint’s firing ports with bullets. Under cover of this fusillade the sergeant wriggled around and to the rear of the pillbox. He emptied his Garand into a rear opening. His fifth bullet struck a mine inside the pill box.

The explosion blew the coconut-log-covered emplacement to shreds. It also blew Bouffard ten yards across the hillside and stripped him naked. Otherwise he was unhurt. Against the scorched slope his nudeness made an excellent target. Machine-guns from two other strongpoints fired at the naked sergeant.

Bouffard, flat on his belly, shouted with rage. He shouted for flame-throwers. He led the charge like an angry Adam storming the serpent’s roost. Both pillboxes were reduced and twenty-three Japs lost their lives in the affray. Bouffard summoned his assistant squad leader.

“Here, Jack,” he said. “Take over. I’m going back to pull the pants off somebody.”

Sergeant Guiseppe Giancarli of Trenton, New Jersey, was the leader of a demolition team. Their job, one day near Davao, was to blow up a number of captured pillboxes to deny their use to enemy night infiltration. As he approached one of the abandoned strongholds he detected a muffled sound of digging. Except for two dead Japanese the pillbox was empty— but the sounds of digging continued.

Giancarli put his ear to the ground. He judged correctly that some Japs were tunneling from another pillbox. He called forward a scout with a submachine gun and they all watched the earthen walls of the pillbox with silent fascination. Eventually a gap opened in the wall and there appeared two yellow fists wielding a shovel. The shoveler and two companions behind him died under the Tommy gun’s bursts. Then Giancarli blew up the pill box with TNT. It was a better grave than most Japs got.

Corporal Charles van Wye of Kansas City, Missouri: I sat behind a machine gun on Hill 550 in the night. It was raining cats and dogs. The Nips were sending over shrapnel rockets, mortar shells and grenades, and we knew that a night attack was brewing.

About fifty yards in front I had stretched a trip wire attached to two booby traps. I heard somebody gallivanting in the bushes but I decided to wait until the trap exploded before I’d open up. They were dragging something through the bushes. Something heavy.

“Bam!”

The booby trap went off and I fired and another gun down the line opened fire too. I poured it into them for a while and then I heard them running downhill. I heard much groaning out in front, so I sprayed the bushes again to put them out of their misery.

Fifteen minutes later they came for more. Our guns pumped about 500 rounds into the bushes before the howling and grenade-play stopped. I was hit in the face, but it wasn’t bad enough to stop me. There was some lightning in the sky and in the flashes of lightning I could see Japs dragging away their dead. So we killed a few more.

They charged twice again before dawn. There’s nothing in the world to compare with a Banzai attack in the dark. They’ve been doing this every night now for a solid week. In the daytime we attack, in the night the Nips counter-attack. That morning we found a lot of dead men, rifles, sabers, and a big box full of dynamite in front of our foxholes.

Private Billie McNew of Harriman, Tennessee: We were just digging in for the night when a Jap machine gun opened up out of a hole we hadn’t noticed. Some guys cried out with pain. Some were killed and there were two who’d been badly wounded. The medic said they should be evacuated right away.

We needed eight men to carry the litters back about a mile to a jeep which could drive them to a hospital. It was a risky thing to do because being out of a hole after dark in Jap territory is plain asking to be killed.

We started out with the wounded and we had a hell of a time getting them over the mucky slopes and through jungle. We had to fight some snipers on the way. Twice we were fired on from our own perimeters. But we made it to a jeep. The men were put on the jeep and we marched a couple miles more to the hospital to clear out the snipers along the road before the jeep could pass in the dark.

Sergeant Fred Dalessio of Philadelphia: We seldom travel alone through Jap country, and whether we do or not we spray every bush whether we see Nips sitting in the bush or not. But that day on Hill 550 my platoon leader couldn’t spare another man and he sent me out alone with a message for the company commander.

So, crawling uphill through the brush I hit a little path and then I looked into the eyes of a Jap two feet away. The Jap was in a pillbox commanding the trail and he was sitting behind a machine gun. I took one big jump and got on top of the position. I thought I’d be pretty safe there until I thought out what I could do.

I couldn’t lean over and shoot into the opening and I didn’t have any grenades. So I hollered to my buddies to throw me a couple of phosphorus grenades. One of ’em crawled up and tossed me the grenades. The Jap in the pillbox was firing like mad, but he couldn’t get out of it. I tossed the grenades and fried him to a crisp.

Private Bennie Butler of Richmond, Virginia: A Jap pillbox suddenly fired. Two men in my squad were hit and we all hugged the ground. My squad leader called me to come up with a couple of grenades. He pointed at the pillbox about ten yards away and said, “See it? — Okay, knock it out.” I gulped. I took off my pack and put down my rifle and started inching around the flank, a grenade in each hand. When I got about two yards off I tossed them into the pillbox. The explosion shook the ground under me. Then I looked inside and saw two dead Japs. After that we blew up the pillbox with TNT to make sure no other Japs would sneak back into it after dark.

First Lieutenant Robert H. Bourne of Grand Rapids, Michigan: I was directing fire from Cannon Company by telephone.

“Range two thousand, right twenty degrees,” was my order.

A chirping voice interrupted me in perfect English.

“What is the exact location of your guns?” it chirped.

“What the hell’s it to you?” I snapped back.

Abruptly the line went dead. Some Jap had made a “party line” out of my field communication.

Davao nights! One night the men along a company perimeter heard the noises of a weird saturnalia. Japs were brawling and singing. There was a wholesale destruction of their own supplies. They blew up seventy-five of their own caves. Debris flew over a radius of five hundred yards. Japs were killed staggering toward the perimeter swinging bottles of sake and chanting. One Japanese sang “The Last Roundup” in English. Next morning riflemen found that Japs had killed some of their own. They had raped and killed Filipino women and children in the village of Tugbok. There, and in five other villages all Filipino civilians had been murdered. There was one Jap officer, dead and mutilated, his hands tied with wire behind his back.

Private Thomas Mechling of Cleveland, Ohio: I had just joined the company and it was my first combat mission.

When the fight with the Japs developed, I was out to the flank of the patrol. I dropped down in jungle grass. Bullets were whizzing around me, but I couldn’t see the Japs.

About the time the firing stopped, an artillery shell exploded close to me and I was dazed. When I recovered I looked for the patrol, but it was gone. I didn’t know how much time had passed.

I remained where I was the rest of the day and that night, thinking that perhaps our troops would appear. They didn’t show up by the next afternoon, so I started through the jungle to the west, where I thought the company was located.

In a few minutes I came to a road. The first thing I saw was a Jap soldier. He was working at a bridge a few hundred feet away, with a group of other Japs. I went back into the brush.

I walked until dark and then I stopped in a deserted native hut near a coconut grove. I stayed there a while and started out again. I never felt so alone in my life.

After walking in circles I returned to the hut for the third time. I decided to spend the night there. After that I didn’t try to move at night. I just slept in the jungle or found a deserted native hut.

I lost track of time after that, just kept wandering through the jungle. There were bananas left behind by the Japs when they retreated from bivouac areas. That is all I ate.

Once I met a Jap face to face and shot him. Another time I threw a grenade at one. I had found the grenade about fifteen minutes before that in the fork of a tree. I didn’t wait to see what happened.

Four days before I was found I met two Japs who saw me before I saw them. I had been sleeping. One of them took my Tommy gun and ran off down the road, leaving the other to take care of me.

The Jap pricked me with his bayonet. Then he motioned me forward. As I started to pass him I hit him in the face with both fists and knocked him down. Then I ran. I was unarmed and half scared to death.

At the time I had been carrying my jacket under my arm, because of the heat rash on my body. I lost it in the scuffle with the Jap, and I surely did miss it when the mosquitoes started biting that night.

Two days later I again met a Jap who saw me first. He raised his rifle and I put up my hands. I said, “Me Filipino,” pretending that I could not speak English. I don’t know whether he understood or not. I do know that I could not understand what he said or the motions he made.

Finally he made a motion with his rifle. I walked close to him, swung my arms down and knocked the rifle to one side. Then I knocked him down. The rifle fell. I picked it up and shot the Jap through the chest. Then I ran for cover.

A little later as I walked on a trail a Jap stepped from the brush and fired at me. I ran into the jungle and ran into another one. He fired at me, but missed. I grabbed my stomach, pretending I was hit, ran a few yards and dropped down.

The Jap started shouting and in a minute he was joined by a companion. They started toward me and I jumped up and ran.

I staggered away from that vicinity and entered a small village which the Japs had evacuated. There were a lot of machine tools and much equipment around. The village was covered with trenches and machine gun nests. In one of the nests I saw dead Japs who had been mashed by our artillery.

I thought sure I would run into American soldiers around there. But I didn’t.

Late in the day I climbed a hill and saw the ocean to the south. That night I could hear the Japs firing mortars about 150 yards above me, to the south, and I felt sure that was where I would find our troops. I tried to sleep but mosquitoes and big ants kept me awake.

Next morning I started southward along a road but ran into a number of Japs who were being shuttled away from a bivouac in trucks. I watched the trucks make several trips, then started out through the brush.

I ran into a burned-over area and through beds of glowing embers. I was half-way across when a Jap, sitting along the road, spotted me. He fired as I turned around and ran back. I felt a sting in my chest, but kept on going.

A bullet had hit me in the back and come out through the chest. Things were sort of faraway and peaceful and I thought I was going to die and nobody would ever find me.

Next thing I knew some Filipinos were carrying me on a board.

The brawny Oregonian balanced the Samurai saber on bandaged hands.

“This isn’t a pretty souvenir,” said Private William W. Mullen, “but it did its work for me.”

He had twisted it from the hands of a Japanese officer and killed him with it.

It was in the sun-beaten hills west of Davao. Mullen’s squad was on flank patrol for a spearhead of tanks.

The attack moved forward until a tank trap halted the rolling steel. That meant a pause for the infantrymen. They squatted in the jungle grass to rest. Men were close to each other, but in the dense growth they could not see one another.

“I was sitting with my B.A.R. across my knees,” said Mullen. ‘It seemed peaceful in there, but all of a sudden I heard a rustling in the grass. I looked up and there was a Nip aiming a pistol at me.

“I swung the automatic rifle in his direction and the burst smashed his legs at the hips. Like puppets pulled by a string, five more Jap soldiers popped up, rifles popping toward their shoulders.

“I emptied the magazine.

“The Japs fell in huddles. It had happened so fast that my buddies who were watching had not fired a shot.

“In the silence I began to feel nervous. Where I was the grass was scorched. I felt like a man sitting in a show window. So I moved over where it was thicker and started fumbling in my ammunition pouch to get out a fresh clip.

“Before I could reload my weapon two more Nips leaped up.

“One was an officer with this saber. He was a six-foot Japanese. The other was a little guy with a rifle that had a bayonet on it. The big one with the saber jumped me. I dropped my empty B.A.R. and ducked. The next time he swung with both hands. The saber grazed my hand, but it was tougher luck for him. He had put so much into it that he lost his balance.

“I jumped at him then. I grabbed the blade and twisted it from the guy’s grip. The officer was thrown to the ground. That’s when I cut my hands.

“I got one stab at him before he started to scramble to his feet. Then I jumped on him, feet first, to break his spine. But I slipped and landed spraddled on his back. Before I could finish him off I heard the second Jap charge me.

“The other soldier had probably been afraid to mix in earlier for fear of killing his own officer, but he was making no bones about it now. I looked over my shoulder and froze. I knew my number was up. He had his rifle stuck out in front of him and the bayonet was coming straight for my back.

“I heard a shot and closed my eyes. Something hit me in the back like a sack of beans and rolled off on the ground. It was the second Jap. One of my buddies had come up and shot him.

“The little Jap wasn’t dead, but he was wounded. He still had hold of his rifle. I don’t know how I did it, but I took the rifle and bayonet from the one lying beside me and threw it out of his reach while I sat on the officer. They were both pretty weak by that time.

“Then I hacked at both of their necks until I was sure that they were dead.”

Corporal James W. Thompson of Coleman, Texas, stared hard at the coconut palm.

Then he dropped flat to the ground. His companion, Sergeant Timothy Mahoney of Gardner, Massachusetts, said:

“There’s a sniper in that tree.”

Slowly, they raised their rifles.

“Don’t shoot— I’m Hernandez.”

It was more like a weak croak than a man’s voice. But it stopped them.

“I’m an American. I’m Hernandez of ‘Charlie’ Company,” it came again.

“Shall we fire?” whispered Thompson.

“Better hold it,” said Mahoney. He called out: “Who’s your regimental commander?”

There was a pause.

“I’m from ‘Charlie’ Company,” said the voice. “Captain Childs is my commander.”

The scouts were from “Mike” Company. They didn’t know the “C” Company commander.

“Let’s take a chance,” said Mahoney. He shouted, “Climb out of that tree.”

A dirty, bewhiskered form more fell than climbed from the tree and staggered toward them. They halted him once for a brief examination, then let him fall forward into their arms.

“Thank God,” the rescued man sobbed.

He was Private Manuel C. Hernandez of Oxnard, California. He had spent eleven days inside the Japanese defense lines, hungry, thirsty, shocked by American artillery fire and air strikes.

His company had established a road block near Mintal, on the outskirts of Davao. The Japanese had attacked this block with overwhelming force. “Charlie” Company was cut off from its battalion through twenty-six hellish hours.

Another company had finally broken through and they had drawn back together into Mintal where they held.

“I didn’t know a relief was fighting through to us,” said Hernandez. “I crawled down to a little creek for water. It was kept under fire by the Japs, but I was so thirsty I didn’t care.

“I never reached that stream. I must have fainted. I came to with an empty feeling in my stomach. The firing had stopped and I didn’t know what to make of it. But it didn’t take me long to find out. I raised up a little and there were Japs all around. My company had gone.

“I crawled on to the water and drank from the muddy brook.

I filled my canteen and pulled myself back into the kunai. It was quiet for a long time. Dive bombers woke me up next morning. Plane after plane dove into the Nip positions. They dropped Napalm and high explosive bombs all around me. I was covered with dirt and leaves by the explosions, and I guess that helped hide me. The Japs were excited and afraid and they ran all around my position. Maybe they thought I was dead. Maybe they were too busy getting out of there to care. Most of them were killed by the bombs or by the bullets when the planes came back and strafed.

“I was knocked deaf for a while, but I knew I had to change my position. I crawled to a big tree. The Japs didn’t scare me any more, but those planes did. I thought the air strike was in advance of an American push, so I went up into the tree so I could see.

“I saw an advance all right, but it wasn’t Americans. They were Nips.

“That movement brought our artillery down on the area again. They weren’t shooting at a point. They were just shooting over the whole place. It seemed like it lasted for hours. Trees fell all around me and shrapnel whanged into my tree. I hung tight I was afraid to move. Down below the Japs fell like flies.

“I had decided to go after water again that night, but it started to rain and I caught enough in my helmet to fill my canteen and myself. I spent that night and the next in the tree. I couldn’t see any Japs, but I knew that they were around, and I was so weak I was afraid to climb down. Then I stayed there an other day and night and another. Every time I thought of coming down I would see some Japs and would hang on a little longer.

“The fifth day I was so hungry something had to happen. I was seeing things, steaks, and such, and I thought I heard girls laugh at me. I managed to fall out of the tree without hurting myself and found a papaya tree the artillery had knocked down. It had one ripe papaya. I ate half of it and put the rest in my pack. Then I took a nap and got some water. That gave me strength and courage.

“I hunted around in the packs of the dead Japs for food. There wasn’t any. But across the little river I saw a shack with smoke coming from the roof. I crawled toward it.

“When I got pretty close a Jap soldier looked out of the window and saw me. Before I could aim my rifle he ran into the jungle. I lay by a tree until evening and watched and he didn’t come back, so I went on up. I made two circles around the house before going in. But it was all in vain. The rice he had been cooking was burned black. I went back to my pack and ate the rest of the papaya.

“I heard American rifle fire that night, but I was too weak to go toward it.

“The next morning I climbed my tree again.

“Things got pretty blurred after that. I saw and heard the strangest things but they weren’t real. One minute I thought I was at a school dance, and the next I was chased by a crocodile. Days and nights came and went. There were more bombings and shellings and strafing. I strapped myself with my belt so I wouldn’t fall out of the tree and I guess I was unconscious most of the time.

“Then I saw that two-man patrol. I just happened to wake up and see it, and I thought that wasn’t real either. But when I looked into those muzzles I woke up. I cried, I was so glad. I started calling to them, but I couldn’t make them hear me and I was afraid they were not real. Then they saw me and almost shot me. That moment I was more afraid than I ever had been before.”

Private First Class Raymond Skrobuton of Chicago, Illinois: Twelve of us — six to a foxhole — were guarding a bridge. Each foxhole had a .30-caliber machine gun. But the rain came down in sheets all night and our guns became useless. We couldn’t hear a thing but the drumming of the rain and occasionally one of our booby traps going off.

Around one o’clock when Harry Pope (of Blackfoot, Idaho) and I were looking out toward the stream, three Japs jumped into our foxhole from the rear. I looked around and it seemed all of our men were gone. So I took off into the darkness. About twenty feet away in the stream I lay down in water with my head on a log.

Two Japs came wading up the stream. They stopped and felt my head and then my body. Then they went toward the foxhole, apparently thinking I was dead.

Pretty soon another Jap came along and I held my head under water. But he stood there so long I was forced to come up for air. I jumped up, knocked the rifle out of his hands, and grabbed it to bayonet him with. I lunged, but the Jap grabbed the rifle and pushed it aside. I pulled back sharply, but in the meantime he released the bayonet and charged me with it. I jumped in close and grabbed him. We fought for that bayonet. Finally I took it away from him, but he bit my finger.

I was slashing away at him when I heard a grenade thrown at us from a foxhole. We both fell in the water, but were blown out by the concussion of the grenade. I slashed him a couple more times and he bit my hand again and hung on. I kicked him in the stomach until he let go.

Another grenade went off and we went into the water again. We fought our way out. I felt weak and he was bleeding all over me. He had my shoulders pinned down and he was hitting me. Then I remembered the penknife I had in my pocket. With my free hand I took my knife out of my pocket and opened it with my teeth. I slashed his face. He weakened and I slit at his throat. Then I pushed his head under water with my foot and drowned him.

After that I crawled under a banana tree and lay there. Flashes of lightning showed a Jap lying beside me. I was too weak to move or try to get him. When daylight came I saw that he was dead.[3]

Sergeant Joseph Helwig of Ashland, Pennsylvania: I went forward with a twenty-five-man patrol to reconnoiter a nest full of Japs. As we reached a cliff-like river bank we were attacked from both flanks and from the rear. The Japanese were yelling and shooting and tossing grenades. We hit the ground in a circle and fought back.

I killed two Japs with my carbine. Sometimes a carbine isn’t enough to stop a Jap. There were Japs who kept coming like all wrath even after you’ve put three or four carbine slugs into them. But those two made gurgling noises and fell. Others jumped over them and came on hooting. They were almost on top of us and our backs were to a precipice of the Talomo River.

Well, we had a machine gun. A machine gun is the most important tool in battle. I grabbed it and fired until the metal burned my hands. Meanwhile my comrades were able to scram ble down the cliff.

I was the last man and I didn’t want to leave my gun to the Japs. The gun was sizzling hot — as hot as a red-hot stove in February back home. My hands were seared and I could smell it. I wrapped my jacket around the gun and pressed the whole thing against my chest and tumbled down the steep bank and started to cross the river.

I got out to the middle of the river all right, but then came trouble. The current knocked me off balance. I started to drift downstream. I hung on to my gun with one hand and paddled with the other. I paddled like never anybody in all time has paddled before. Frantic, that’s the word. One of my buddies on the other bank saw my predicament and he waded out some distance downstream and held out a bamboo pole for me to grasp. All this time the Japs followed us down the river.

I clutched the end of the bamboo pole with one hand and held on. The current swung me in an arc and then into a mud bank.

The fellows in my platoon — those that weren’t hit too bad — had climbed up the bank of the river and there they were pinned down by the same hooting bunch of Japs. The Japs were firing across the river. I scrambled up the bank. On the way I lost my machine gun and it fell back down into the river. I dived after it and retrieved it and scrambled up the bank again. There I set up the gun and swung it into action. A guy came running with a box of ammunition. He was feeding the gun. I fired. A third man behind a tree higher up acted as our observer.

I sprayed the area from right to left and then back again from left to right. The gun was smoking and red. The heat burned my eyebrows and melted the front sight and I smelled oil burning inside the mechanism. I fired up four boxes — an even thousand rounds. There was a mess of dead and dying Nips along the river, but there were others still brimming with fight. Some of my buddies were stung by Jap slugs and one guy was crying for his mother. The rest had pulled back to better positions.

I told my observer to get the hell out of here while he could. My assistant and I dismounted the gun and started to crawl back too.

Then my buddy got hit in the leg. A bone was snapped and he couldn’t walk. It was getting dark and the rest of the patrol had gone. I heard a radio operator in the bushes trying to get in touch with friendly troops. I had to act fast. I thought I’d rather be cursed and damned than let the Japs get my gun. So I crawled into a thicket and dug a hole with my hands where the earth was soft. I buried the gun and covered it up with leaves and then I went back to get my wounded buddy.

My buddy groaned. He was trying to tell me something. Finally I could hear him. “Japs are coming up the trail,” he said.

I saw the Japs and I grabbed my carbine and pumped fifteen shots in their direction. It was too dark to see much, but one of them fell on his face and the rest faded into the bushes.

It wasn’t safe to sit up. I told my buddy to grab hold of my leg and hang on. That’s what he did. I kept creeping along on my with my buddy trailing behind. Pretty soon I was too tired to move. I just felt too tired to pull myself forward another inch. So I stopped. There was a track of blood where I’d dragged my buddy through the undergrowth. Mosquitoes were buzzing around us. My buddy was faint. I leaned over him and cut away his pants to bandage his wound, but his bone was sticking out. I cut a couple of sticks to use as splints and started to work. All of a sudden he sighed and went limp. A burst of machine gun bullets had gone through him.

I almost cracked. There’s just so much a man can stand before he cracks. I’d gone through four campaigns and I’ve been hit twice in this Jap-war, and I never felt so near cracking as I did that night. Then I noticed that my dead buddy still had his Tommy gun strapped over his shoulder. I rolled him into the bushes and spoke the beginning of the Lord’s Prayer. Then I buried his Tommy gun and started to look for my patrol.

They must have left me for dead. I crawled around for a while and all I could find were Japs slithering through the bushes. It was very dark by now. Better lie still, I thought. If you move around your buddies will shoot you for sure if the Japs miss you.

I saw the tracers whizzing and here and there one of them plunked into a tree trunk and burned for a second like a blue-and-yellow butterfly. Japs were shouting to each other in the dark. Some grenades exploded somewhere. A storm came up and the rain came down like a solid waterfall. Then mortar shells started dropping. They hit the treetops and burst right there and the fragments whined down into the jungle.

They were our own mortar shells. No duds. Not one. Our mortars were shelling the Japs. But mortar shells don’t know the difference between an American and a Jap. I dived between two rocks and gashed my knee. An explosion threw a barrel of mud into my face. I kept creeping and crawling in and out of fox holes that the Japs had dug. Jap holes are deep, much deeper than we dig ’em. Most of them were half full of water but I was soaked through anyway. Finally I got out of range.

I crawled into the bushes and rested. I got rid of everything metal that might clink or reflect the lightning. Lightning was coming down into the woods. The rain and the lightning went on all night. My carbine was full of mud but I washed it in the rain and kept it under my jacket. The Japs were scouting. They passed in groups four to five men strong, as silent as wraiths. I saw my whole past glide by me as I waited. I shook hands with myself and said goodbye to everyone I knew.

The night was as long as hell. Dawn was slow in coming. I shivered with fever. I crawled out on the trail and looked for footprints. The rain had wiped them away. I lurched through the woods until I came to a wire. That was U.S. wire. I followed the wire to an outpost. They gave me coffee and I fainted.

When I woke up I was in an ambulance. There were some soldiers in the ambulance and a corpsman worked over them and the door was open. Out there stood some guys talking. Just then a blond kid came running up from the command post. He had mud on his face and he was very excited.

‘The Old Man got it on the radio,” he said. “Germany has surrendered.”

Everybody stopped talking. Nobody asked a question. Nobody said a word. Nobody smiled. Only one of the wounded fellows tossed around and moaned a little bit. Jap artillery and our artillery were busy over Davao, and the sound of machine gun fire was over the hills like an evil cloud.

Private First Class Abel Souza of Oakland, California: I don’t want to tell you about myself. I want to tell you about my buddy, James Diamond, whose home is in Gulfport, Mississippi. He can’t talk for himself because he is dead. A sniper killed him by the Talomo River.

James Diamond became my buddy when the Division was rooting Japs from the woods in New Guinea. We fought on Breakneck Ridge together, out there in the rain of Leyte, and after that we killed Japs in Lubang and then we hit Mindanao and hiked a hundred miles over the mountains, and when we came to Davao we were still buddies.

Both of us were fighting in bloody Mintal, in the hemp hell around Libby Drome, and along the Talomo River where the Japs had machine guns and artillery dug in above the steep banks.

One day we crossed that river under fire and struggled up the opposite side and suddenly three pillboxes and a lot of snipers gave us hell. Some guys were hit and lay on the ground, screaming, and there were some who were dead, and some who lost their footing in the river and rolled downstream with the current. Everybody lay low. Nobody dared to move except the wounded who had to kill their agony. The snipers and machine guns were playing lead our way and more guys were hit. Then James Diamond got up without a word.

Let me tell you about Jim Diamond. He was a friendly sort of guy. He liked to talk, and he liked girls, and he was doing things all the time. He was a ball player, too. He was tall and blond and husky, and maybe twenty-six years old. He had a good brain, and he figured he’d be going home to Mississippi before the year was over. Well, Jim got up when the sniper nearest to us started tossing grenades. The grenades exploded and we could hear the slivers whizzing past us. Jim went out to get that sniper. The sniper threw another grenade and Jim called to us to keep low. Then he pounced on the sniper and killed him.

By that time some howitzers were sweating across the river and Jim stood up again and directed the fire from their guns and cannon on the pillboxes and the other snipers. He just stood there in the open and pointed his arm at the spots he wanted the armor to hit. This gave us others a chance to put one of our machine guns into action and Jim came back to us and grinned.

But a little later a burst from one of the Jap pillboxes knocked away one of the legs of our machine gun tripod and the gun toppled over and stopped firing. The Nips saw their chance and rushed forward. Jim Diamond was on his feet again faster than I can say it. He sprayed the Japs with his submachine gun and forced them down until we were set up again for action. After that he called for the tank destroyers to come forward but they wouldn’t come. So Jim went back and climbed on the turret of one and showed them where the Japs were dug in, and pretty soon some more pillboxes were knocked out.

That night we spent on the perimeter, in foxholes, one man watching, the other trying to sleep under his poncho. There was a little bit of trouble when Japs tried to sneak in, but nothing much came of it except that it kept us all awake and we were mad. The mosquitoes were vicious up there and we were bothered by ants and centipedes. Jim let me use the last of his insect repellent to rub on my ears, hands, knees and elbows.

Next morning we ate cold rations and attacked again. A number of guys were wounded and things were so hot that the aid men had trouble coming through. Jap bullets and mortar shells boiled the water of the river and it looked as if nobody could go across. Jim Diamond stood up and jammed his helmet on hard and said he’d carry the wounded guys back across the river. That river ran fast and it was five feet deep. Jap artillery had smashed a bridge our engineers had put up the day before. We all thought that it couldn’t be done, that nobody could get across and live. But Jim did it. And seeing him, we pitched in and helped.

In the afternoon Jim was hit by fragments from a bursting Jap shell. He was bleeding and you could see by his face that he was in pain. But he was so intent on helping the other wounded across the river that he would not lay low and have himself fixed up. Nobody would have blamed him if he’d grasped that chance to get himself sent to the rear. Four campaigns, that’s a hell of a lot of shooting and hardship most people will never know of. A fellow’s luck can’t hold out all the time. The longer you’re in this the more you have the feeling that soon there’s a bullet coming your way. Jim must have had that feeling.

He worked across the river and went to a jeep somebody had left there for dead. He tried the jeep and it ran. He loaded two of the wounded guys in the jeep and drove off through the mortar and artillery barrage the Japs were putting down on the road to cut us off. Jim Diamond got through and came back and loaded two more wounded in his jeep. He made that trip four times and carried out eight hurt soldiers, and that means that he drove eight times through the shell bursts. All four tires of his jeep were mangled by shrapnel before he was finished. I felt so proud of my buddy that I could have wept.

Next day we got orders to fall back and give up the bridgehead across the Talomo River. They needed our battalion for a flank attack, they said. One squad was sent to the river bank to try to repair the shot-out bridge. But fire was so heavy that the squad could not work there. It looked as if we were trapped for good.

Jim Diamond stood up and said that he’d go and repair that bridge so that the battalion could carry out its orders.

“Jim,” I said, “I’m goin’ with you.”

Together we ducked to the river bank. There were a lot of broken timbers around and some rope the engineers had left behind, and there was also a roll of telephone wire. Just then the mortar barrage opened up again and we both thought we couldn’t make it.

“We’ll do it anyway,” said Jim.

We repaired that bridge with frayed timbers and rope. It wasn’t much of a bridge, but enough for a man in trouble to run over if he’s learned how to keep his balance.

The battalion got across all right in small groups, and on the rush. It was pitch dark nighttime. The Japs sensed our retreat and followed it up, thinking they could wipe us out. Fifty-nine Japs were killed in that counter attack. Then Jim worked most of the night bringing the wounded out of the danger line. Every body in the company kidded him by calling him the “incredible Diamond.”

A few days later our battalion was cut off in another sector, and we had no food and water, and we were running low on ammunition. Jim stood up and volunteered to lead a patrol through five hundred yards of thickets full of Japs to bring out our wounded and to bring in water and supplies. After they’d gone about half way, a Jap machine gunner spotted them and raked them with lead. One man in the patrol was wounded. All others hugged the ground and wondered what to do next. There wasn’t the tiniest hope to get away unless we could bring strong offensive fire to bear on the Japs.

Suddenly Jim shouted. He had spotted an abandoned machine gun some fifty yards away. An ammunition belt ran through that gun and there was an ammunition box standing next to it. Jim dropped his Tommy gun and made a fast rush toward that machine gun. He would turn that gun on the Japs and force them to duck and that’d make it possible for us to back out of the trap. He almost reached that gun. Somewhere some sniper fired a single shot and Jim pitched to the ground.

He was still alive when we dragged him with us as we fought our way back to our battalion. He tried to be helpful and he was quiet and said nothing. We put him on his way to a hospital. The next we heard was that he’d died before he got there.

He was buried and we wept. We all felt that Jim Diamond should never have died. He’d been due to go home. But our rifles kept roaring, and what they said was — cursed be anybody among us or back home who thinks that Jim Diamond did not sacrifice his life for him.

(Continue to Chapter 22: Surrender)

_____________________________________________________

[1] Major William T. Cameron, of Philippine Civil Affairs Unit 29, formerly Master of the High School of Commerce, Boston.

[2] As quoted by Associated Press.

[3] As told to Walter Simmons, Chicago Tribune front line correspondent.