Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Vanishing Roads and Other Essays, by Richard Le Gallienne (published 1915). All spelling in the original.

The longevity of trees is said to be in proportion to the slowness of their growth. It has to do no little as well with the depth and area of their roots and the richness of the soil in which they find themselves. When the sower went forth to sow, it will be remembered, that which soon sprang up as soon withered away. It was the seed that was content to “bring forth fruit with patience” that finally won out and survived the others.

These humble, old-fashioned illustrations occur to me as I apply myself to the consideration of the question provoked by the lightning over-production of modern fiction and modern literature generally: the question of the flourishing longevity of the fiction of the past as compared with the swift oblivion which seems almost invariably to over-take the much-advertised “masterpieces” of the present.

I read somewhere a ballad asking—where are the “best sellers” of yesteryear? The ballad-maker might well ask, and one might re-echo with Villon: “Mother of God, ah! where are they?” During the last twenty years they have been as the sands on the seashore for multitude, yet I think one would be hard set to name a dozen of them whose titles even are still on the lips of men—whereas several quieter books published during that same period, unheralded by trumpet or fire-balloon, are seen serenely to be ascending to a sure place in the literary firmament.

What can be the reason? Can the decay of these forgotten phenomena of modern fiction, so lavishly crowned with laurels manufactured in the offices of their own publishers, have anything to do with the hectic rapidity of their growth, and may there be some truth in the supposition that the novels, and books generally, that live longest are those that took the longest to write, or, at all events underwent the longest periods of gestation?

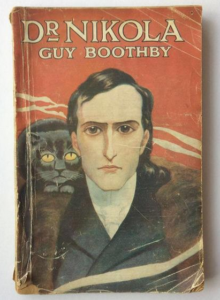

Some fifteen years or so ago one of the most successful manufacturers of best sellers was Guy Boothby, whose Dr. Nikola is perhaps still remembered. Unhappily he did not live long to enjoy the fruits of his industrious dexterity. I bring his case to mind as typical of the modern machine-made methods.

I had read in a newspaper that he did his “writing” by phonograph, and chancing to meet him somewhere, asked him about it. His response was to invite me to come down to his charming country house on the Thames and see how he did it. Boothby was a fine, manly fellow, utterly without “side” or any illusions as to the quality of his work. He loved good literature too well—Walter Pater, incongruously enough, was one of his idols—to dream that he could make it. Nor was the making of literature by any means his first preoccupation, as he made clear, with winning frankness, within a few moments of my arriving at his home.

Taking me out into his grounds, he brought me to some extensive kennels, where he showed me with pride some fifty or so prize dogs; then he took me to his stables, his face shining with pleasure in his thoroughbreds; and again he led the way to a vast hennery, populated with innumerable prize fowls.

“These are the things I care about,” he said, “and I write the stuff for which it appears I have a certain knack only because it enables me to buy them!”

Would that all writers of best sellers were as engagingly honest. No few of them, however, write no better and affect the airs of genius into the bargain.

Then Boothby took me into his “study,” the entire literary apparatus of which consisted of three phonographs; and he explained that, when he had dictated a certain amount of a novel into one of them, he handed it over to his secretary in another room, who set it going and transcribed what he had spoken into the machine; he, meanwhile, proceeding to fill up another record. And he concluded airily by saying with a laugh that he had a novel of 60,000 words to deliver in ten days, and was just on the point of beginning it!

Boothby’s method was, I believe, somewhat unusual in those days. Since then it has become something like the rule. Not so much as regards the phonograph, perhaps, but with respect to the breathless speed of production.

I am informed by an editor, associated with magazines that use no less than a million and a half words of fiction a month, that he has among his contributors more than one writer on whom he can rely to turn off a novel of 60,000 words in six days, and that he can put his finger on twenty novelists who think nothing of writing a novel of a hundred thousand words in anywhere from sixty to ninety days. He recalled to me, too, the case of a well-known novelist who has recently contracted to supply a publisher with four novels in one year, each novel to run to not less than a hundred thousand words. One thinks of the Scotsman with his “Where’s your Willie Shakespeare now?”

Even Balzac’s titanic industry must hide its diminished head before such appalling fecundity; and what would Horace have to say to such frog-like verbal spawning, with his famous “labour of the file” and his counsel to writers “to take a subject equal to your powers, and consider long what your shoulders refuse, what they are able to bear.” It is to be feared that “the monument more enduring than brass” is not erected with such rapidity. The only brass associated with the modern best seller is to be found in the advertisements; and, indeed, all that both purveyor and consumer seem to care about may well be summed up in the publisher’s recommendation quoted by Professor Phelps: “This book goes with a rush and ends with a smash.” Such, one might add, is the beginning and ending of all literary rockets.

Now let us recall some fiction that has been in the world anywhere from, say, three hundred years to fifty years and is yet vigorously alive, and, in many instances, to be classed still with the best sellers.

Don Quixote, for example, was published in 1605, but is still actively selling. Why? May it perhaps be that it was some six years in the writing, and that a great man, who was soldier as well as writer, charged it with the vitality of all his blood and tears and laughter, all the hard-won humanity of years of manful living, those five years as a slave in Algiers (actually beginning it in prison once more at La Mancha), and all the stern struggle of a storm-tossed life faced with heroic steadfastness and gaiety of heart?

Take another book which, if it is not read as much as it used to be, and still deserves to be, is certainly far from being forgotten—Gil Blas. Published in 1715—that is, its first two parts—it has now two centuries of popularity to its credit, and is still as racy with humanity as ever; but, though Le Sage was a rapid and voluminous writer, over this one book which alone the world remembers it is significant to note that he expended unusual time and pains. He was forty-seven years old when the first two parts were published. The third part was not published till 1724, and eleven years more were to elapse before the issue of the fourth and final part in 1735.

A still older book that is still one of the world’s best sellers, The Pilgrim’s Progress, can hardly be conceived as being dashed off in sixty or ninety days, and would hardly have endured so long had not Bunyan put into it those twelve years of soul torment in Bedford gaol. Robinson Crusoe still sells its annual thousands, whereas others of its author’s books no less skilfully written are practically forgotten, doubtless because Defoe, fifty-eight years old at its publication, had concentrated in it the ripe experience of a lifetime. Though a boy’s book to us, he clearly intended it for an allegory of his own arduous, solitary life.

“I, Robinson Crusoe,” we read, “do affirm that the story, though allegorical, is also historical, and that it is the beautiful representation of a life of unexampled misfortune, and of a variety not to be met with in this world.”

The Vicar of Wakefield, as we know, was no hurried piece of work. Indeed, Goldsmith went about it in so leisurely a fashion as to leave it neglected in a drawer of his desk, till Johnson rescued it, according to the proverbial anecdote; and even then its publisher, Newbery, was in no hurry, for he kept it by him another two years before giving it to the printer and to immortality. It was certainly one of those fruits “brought forth with patience” all round.

Tom Jones is another such slow-growing masterpiece. Written in the sad years immediately following the death of his dearly loved wife, Fielding, dedicating it to Lord Lyttelton, says: “I here present you with the labours of some years of my life”; and it need scarcely be added that the book, as in the case of all real masterpieces, represented not merely the time expended on it, but all the accumulated experience of Fielding’s very human history.

Yes! Whistler’s famous answer to Ruskin’s counsel holds good of all imperishable literature. Had he the assurance to ask two hundred guineas for a picture that only took a day to paint? No, replied Whistler, he asked it for “the training of a lifetime”; and it is this training of a lifetime, in addition to the actual time expended on composition, that constitutes the reserve force of all great works of fiction, and is entirely lacking in most modern novels, however superficially brilliant be their workmanship.

For this reason books like George Borrow’s Lavengro and Romany Rye, failures on their publication, grow greater rather than less with the passage of time. Their writers, out of the sheer sincerity of their natures, furnished them, as by magic, with an inexhaustible provision of life-giving “ichor.” To quote from Milton, “a good book is the precious life-blood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.”

Of this immortality principle in literature Milton himself, it need hardly be said, is one of the great exemplars. He was but thirty-two when he first projected Paradise Lost, and through all the intervening years of hazardous political industry he had kept the seed warm in his heart, its fruit only to be brought forth with tragic patience in those seven years of blindness and imminent peril of the scaffold which followed his fiftieth birthday.

The case of poets is not irrelevant to our theme, for the conditions of all great literature, whatever its nature, are the same. Therefore, we may recall Dante, whose Divine Comedy was with him from his thirty-fifth year till the year of his death, the bitter-sweet companion of twenty years of exile. Goethe, again, finished at eighty the Faust he had conceived at twenty.

Spenser was at work on his Faerie Queene, alongside his preoccupation with state business, for nearly twenty years. Pope was twelve years translating Homer, and I think there is little doubt that Gray’s Elegy owes much of its staying power to the Horatian deliberation with which Gray polished and repolished it through eight years.

If we are to believe Poe’s Philosophy of Composition, and there is, I think, more truth in it than is generally allowed, the vitality of The Raven, as that, too, of his genuinely imperishable fictions, is less due to inspiration than to the mathematical painstaking of their composition.

But, perhaps, of all poets, the story of Virgil is most instructive for an age of “get-rich-quick” littérateurs. On his Georgics alone he worked seven years, and, after working eleven years on the Aeneid, he was still so dissatisfied with it that on his death-bed he besought his friends to burn it, and on their refusal, commanded his servants to bring the manuscript that he might burn it himself. But, fortunately, Augustus had heard portions of it, and the imperial veto overpowered the poet’s infanticidal desire.

But, to return to the novelists, it may at first sight seem that the great writer who, with the Waverley Novels, inaugurated the modern era of cyclonic booms and mammoth sales, was an exception to the classic formula of creation which we are endeavouring to make good. Stevenson, we have been told, used to despair as he thought of Scott’s “immense fecundity of invention” and “careless, masterly ease.”

“I cannot compete with that,” he says—”what makes me sick is to think of Scott turning out Guy Mannering in three weeks.”

Scott’s speed is, indeed, one of the marvels of literary history, yet in his case, perhaps more than in that of any other novelist, it must be remembered that this speed had, in an unusual degree, that “training of a lifetime” to rely upon; as from his earliest boyhood all Scott’s faculties had been consciously as well as unconsciously engaged in absorbing and, by the aid of his astonishing memory, preserving the vast materials on which he was able thus carelessly to draw.

Moreover, those who have read his manly autobiography know that this speed was by no means all “ease,” as witness the almost tragic composition of The Bride of Lammermoor. If ever a writer scorned delights and lived laborious days, it was Walter Scott. At the same time the condition of his fame in the present day bears out the general truth of my contention, for there is little doubt that he would be more widely read than he is were it not for those too frequent longueurs and inert paddings which resulted from his too hurried workmanship.

Jane Austen is another example of comparatively rapid creation, writing three of her best-known novels, Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, and Northanger Abbey between the ages of twenty-one and twenty-three. Yet Pride and Prejudice, which practically survives the others, took her ten months to complete, and all her writings, it has again to be said, had first been deeply and intimately “lived.”

Charlotte Brontë was a year in writing Jane Eyre, spurred on to new effort by the recent rejection of The Professor; but to write such a book in a year cannot be called over-hasty production when one considers how much of Jane Eyre was drawn from Charlotte Brontë’s own life, and also how she and her sisters had been experimenting with literature from their earliest childhood.

Thackeray considered an allowance of two years sufficient for the writing of a good novel, but that seems little enough when one takes into account the length of his best-known books, not to mention the perfection of their craftsmanship. Dickens, for all the prodigious bulk of his output, was rather a steady than a rapid writer. “He considered,” says Forster, “three of his not very large manuscript pages a good, and four an excellent, day’s work.”

David Copperfield was about a year and nine months in the writing, having been begun in the opening of 1849 and completed in October, 1850. Bleak House took a little longer, having been begun in November, 1851, and completed in August, 1853. Hard Times was a hasty piece of work, written between the winter of 1853, and the summer of 1854, and it cannot be considered one of Dickens’s notable successes.

George Meredith wrote four of his greatest novels in seven years, Richard Feverel, Evan Harrington, Sandra Belloni, and Rhoda Fleming being produced between 1859 and 1866. His poem, Modern Love, was also written during that period.

George Eliot was a much-meditating, painstaking writer, though Adam Bede cost her little more than a year’s work. Her novels, however, as a rule, did not come forth without prayer and fasting, and, in the course of their creation, she used often to suffer from “hopelessness and melancholy.” Romola, to which she devoted long and studious preparation, she was often on the point of giving up, and in regard to it she gives expression to a literary ideal to which the gentleman with the contract for four novels a year, referred to in the outset of this paper, is probably a stranger.

It may turn out [she says], that I can’t work freely and fully enough in the medium I have chosen, and in that case I must give it up; for I will never write anything to which my whole heart, mind, and conscience don’t consent; so that I may feel it was something—however small—which wanted to be done in this world, and that I am just the organ for that small bit of work.

Charles Kingsley who, if not a great novelist, has to his credit in Westward Ho! one romance at least which, in the old phrase, “the world will not willingly let die,” was as conscientious in his work as he was brilliant.

Says a friend who was with him while he was writing Hypatia:

“He took extraordinary pains to be accurate. We spent one whole day in searching the four folio volumes of Synesius for a fact he thought was there, and which was found there at last.”

The writer of perhaps the greatest historical novel in the English language, The Cloister and the Hearth, was what one might call a glutton for thoroughness. Of himself Charles Reade has said: “I studied the great art of fiction closely for fifteen years before I presumed to write a line. I was a ripe critic before I became an artist.” His commonplace books, on the entries in which and the indexing he was accustomed to spend one whole day out of each week, cataloguing the notes of his multifarious reading and pasting in cuttings from newspapers likely to be useful in novel-building, completely filled one of the rooms in his house. In his will he left these open to the inspection of literary students who cared to study the methods which he had found so serviceable.

To name one or two more English novelists: Thomas Hardy’s novels would seem to have the slow growth of deep-rooted things. His greatest work, The Return of the Native, was on the stocks for four years, though a year seems to have sufficed for Far from the Madding Crowd.

The meticulous practice of Stevenson is proverbial, but this glimpse of his method is worth catching again.

The first draft of a story [records Mr. Charles D. Lanier], Stevenson wrote out roughly, or dictated to Lloyd Osbourne. When all the colours were in hand for the complete picture, he invariably penned it himself, with exceeding care…. If the first copy did not please him, he patiently made a second or a third draft. In his stern, self-imposed apprenticeship of phrase-making he had prepared himself for these workmanlike methods by the practice of rewriting his trial stories into dramas and then reworking them into stories again.

Nathaniel Hawthorne brought the devoted, one might say, the devotional, spirit of the true artist to all his work, but The Scarlet Letter was written at a good pace when once started, though, as usual, the germ had been in Hawthorne’s mind for many years. The story of its beginning is one of the many touching anecdotes in that history of authorship which Carlyle compared to the Newgate Calendar. Incidentally, too, it witnesses that an author occasionally meets with a good wife.

One wintry autumn day in Salem, Hawthorne returned home earlier than usual from the custom-house. With pale lips, he said to his wife: “I am turned out of office.” To which she—God bless her!—cheerily replied: “Very well! now you can write your book!” and immediately set about lighting his study fire and generally making things comfortable for his work.

The book was The Scarlet Letter, and was completed by the following February, Hawthorne, as his wife said, writing “immensely” on it day after day, nine hours a day. When finished, Hawthorne seems to have been dispirited about the story, and put it away in a drawer; but the good James T. Fields chanced soon to call on him, and asked him if he had anything for him to publish.

“Who,” asked Hawthorne gloomily, “would risk publishing a book from me, the most unpopular writer in America?”

“I would,” was Field’s rejoinder, and after some further sparring, Hawthorne owned up.

“As you have found me out,” said he, “take what I have written and tell me if it is good for anything”; and Fields went away with the manuscript of what is, without any question, America’s greatest novel.

Turning to the great novelists of France, with one or two exceptions, they all bear out the theory of longevity in literature which I have been endeavouring to support. It must reluctantly be confessed that one of the most fascinatingly vital of them all, Alexandre Dumas, is one of the exceptions, born improvisator as he was; yet immense research, it needs hardly be said, went to the making of his enormous library of romance—even though, it be allowed, that much of that work was done for him by his “disciples.”

George Sand was another facile, all too facile, writer. Here is a description of her method:

To write novels was to her only a process of nature. She seated herself before her table at ten o’clock, with scarcely a plot and only the slightest acquaintance with her characters, and until five in the evening, while her hand guided a pen, the novel wrote itself. Next day, and the next, it was the same. By and by the novel had written itself in full and another was unfolding.

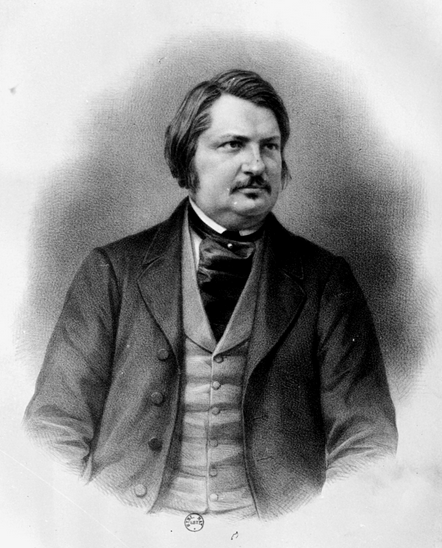

Whether George Sand is still alive as a novelist, apart from her place as an historic personality, I leave others to decide; but I am very sure that she would be read a great deal more than she is if she had not so confidently left her novels—to write themselves. Different, indeed, was the method of Balzac, toiling year after year at his colossal task of The Human Comedy, sometimes working eighteen hours a day, and never less than twelve, and that “in the midst of protested bills, business annoyances, the most cruel financial straits, in utter solitude and lack of all consolation.” But then Balzac was sustained by one of those great dreams, without whose aid no lasting literature is produced, the dream, “by infinite patience and courage, to compose for the France of the nineteenth century, that history of morals which the old civilizations of Rome, Athens, Memphis, and India have left untold.”

To fulfil this he was able to live, for a long period, on a daily expenditure of “three sous for bread, two for milk, and three for firing.” But doubtless it had been different if his dream had been prize puppies, a garage full of motor-cars, or a translation into the Four Hundred.

Victor Hugo, again, was one of the herculean artists, working, in Emerson’s phrase, “in a sad sincerity,” with the patience of an ant and the energy of a volcano. Of his Les Misérables—perhaps the greatest novel ever written, as it is, I suppose, easily the longest—he said, “it takes me nearly as long to publish a book as to write one”; and he was at work on Les Misérables, off and on, for nearly fifteen years. Of his writing Notre Dame (that other colossus of fiction) this quaint picture has been preserved. He had made vast historical preparations for it, but ever there seemed still more to make, till at length his publisher grew impatient, and under his pressure Hugo at last made a start—after this fashion:

He purchased a great grey woollen wrapper that covered him from head to foot, he locked up all his clothes lest he should be tempted to go out, and, carrying off his ink-bottle to his study, applied himself to his labour just as if he had been in prison. He never left the table except for food and sleep, and the sole recreation that he allowed himself was an hour’s chat after dinner with M. Pierre Leroux, or any other friend who might drop in, and to whom he would occasionally read over his day’s work.

Daudet, whose Tartarin bids fair to remain one of the world’s types, like Don Quixote or Mr. Micawber, for all his natural Provençal gift of improvisation and, indeed, from his self-recognized necessity of keeping it in check, was another strenuous artist. He wrote each manuscript three times over, he told his biographer, and would write it as many more if he could; and his son, in writing of him, has this truth to say of his, as of all living work:

The fact is that labour does not begin at the moment when the artist takes his pen. It begins in sustained reflection and in the thought which accumulates images and sifts them, garners and winnows them out, and compels life to keep control over imagination, and imagination to expand and enlarge life.

Zola is perhaps unduly depreciated nowadays, but certainly, if Carlyle’s “infinite capacity for taking pains” as a recipe for genius ever was put to the test, it was by the author of the Rougon-Macquart series. Talking of rewriting, Prosper Mérimée, best known for Carmen, is said to have rewritten his Colomba no less than sixteen times; as our Anglo-Saxon Kipling, it used to be told, wrote his short stories seven times over.

But, of course, the classical example of the artist-fanatic in modern times was Gustave Flaubert. His agonies in quest of the mot propre, the one and only word, are proverbial, and are said literally to have broken down his nerves. Mr. Huneker has told of him that “he would annotate three hundred volumes for a page of facts…. In twenty pages he sometimes saved three or four from destruction,” and, in the course of twenty-six years’ polishing and pruning of The Temptation of Saint Anthony, he reduced his original manuscript of 540 pages down to 136, even reducing it still further after its first publication.

On Madame Bovary he worked six years, and in writing Salâmmbo, which, took him no less time, he studied the scenery on the spot and exhausted the resources of the Imperial Library in his search for documentary evidences.

Flaubert may be said to have carried his passion for perfection to the point of mania, and it will be a question with some whether, with all his pains, he can be called a great novelist, after all. But that he was a great stylist and a master in the art of making terrible and beautiful bas-reliefs admits of no doubt.

To be a great world-novelist you need an all-embracing humanity as well, such as we find in Tolstoy’s War and Peace—but that great book, need one say, came of no slipshod speed of improvisation. On the contrary, Tolstoy corrected and recorrected it so often that his wife, who acted as his amanuensis, is said to have copied the whole enormous manuscript no less than seven times!

Yes! though it be doubtless true, in Mr. Kipling’s famous phrase, that

I think that the whole nine and sixty of them include somewhere in their method those sole preservative virtues of truth to life and passionate artistic integrity. The longest-lived books, whatever their nature, have usually been the longest growing; and even those lasting things of literature that have seemed, as it were, to spring up in a night, have been long in secret preparation in a soil mysteriously enriched and refined by the hid processes of time.