Editor’s note: The following is extracted from One Damned Island After Another, by Clive Howard and Joe Whitley (published 1946).

There were no famous pilots and no famous airplanes in the Seventh Air Force; famous, that is, outside the coral and jungle confines of the 5,000-mile chain of islands which comprised the Seventh’s air command.

The Seventh Air Force had produced no Gabreskis or Bongs. Too often, the Jap fighters were out of range of the Army land-based fighter pilots.

Although the Seventh’s bombers consistently flew the longest missions in the world against the smallest targets, there was no Memphis Belle touring Stateside defense factories to tell the story of the men of the Seventh. For a long time, they didn’t have an airplane or crew which could be spared from the pressing business of war against the Japanese to fly a publicity mission to the States.

They had come rather close to it once with a Liberator named the Bolivar, which flew 186,000 combat miles against twelve Japanese islands from Funafuti to Iwo to complete eighty-one missions and drop 405,000 pounds of bombs. The Bolivar, at the outset of a bond-selling tour which might have given the forgotten Seventh the kind of publicity that was going to other air forces, crashed to an ignominious and untimely end in full view of several thousand Consolidated aircraft workers at Downey, California. The Consolidated plant was the first and only stop on the aborted bond tour.

But there were men and airplanes famous all through the islands of the Central Pacific for accomplishments worthy of remembrance in a theater where the fantastic was commonplace.

Planes like the Texas Belle [1] which, months after it made its parachute landing on Tarawa, was still being talked about in chow lines as far west as Angaur.

And men like Technical Sergeant Guillermo Abrego, a B-24 flight engineer who, after the rest of his crew had parachuted from a disabled bomber 200 miles off Marcus, and without an hour’s flight training, piloted and navigated the shot-up plane 600 miles home to Tinian, only to miss winning one of the greatest gambles of the war when he picked an airstrip only partially completed and crashed to his death.

There was one airplane which achieved everlasting fame among the men of the Seventh for a mission and a crash landing so fantastic that the thousands of men who saw the plane come in on Saipan could never fully believe what they saw.

The airplane was the Chambermaid. So remarkable was its flight home from Iwo, and so devastating its crash landing, that it was the subject of a lengthy and detailed report in the New Yorker Magazine written by a Seventh Air Force man, Sergeant Roger Angell. It was, for the tiny and forgotten Seventh, quite a burst of acclaim….

______________________________

The Chambermaid took off from Saipan early on a morning in September as part of a formation of B-24’s going north to Iwo Jima in tight formation through bad weather.

For the plane, which the crew privately called the House of Bourbon after their cocker mascot, Burma Bourbon, it was the thirty-fifth mission. The Liberator had seen one crew safely through its quota of combat missions. The present crew, with only six missions behind them, were comparative newcomers to combat.

The flight north was uneventful except for bad weather which forced the formation to detour constantly.

Fifteen minutes before Iwo was sighted, the crew of the Chambermaid discovered a flight of eight Jap pursuit planes far below them.

“That was unusual,” said Lieutenant William V. Core, the pilot. “But Iwo had a reputation for being the most unpredictable target in the Pacific anyhow.”

Even more unusual was the fact that the Japs began making long passes at the formation from below. Usually, the Jap fighters held their attack until our planes came out of their bombing runs and broke formation to evade flak.

One of the Zeroes was hit by fire from the B-24’s and blew up. Then, as the Liberators came over the target, the Jap fighters dropped back to let the anti-aircraft do its work.

Lieutenant Core, who had made three previous trips over Iwo but “never saw the damned place,” gave the Chambermaid’s controls to his co-pilot, Lieutenant Glen W. Beatty.

Leaning forward in his seat, Core saw red and white flashes appear all over the island. It made him feel that every Jap down there was firing at his personally.

Lieutenant Melvin K. Harms, the bombardier, released his load over the Chambermaid’s specific target, the installations and storage areas around the airstrip.

Standing over the open bomb bay, Lieutenant Doscher, an Intelligence officer flying that day as observer, and Lieutenant Clarence Wasser, the navigator, watched the bombs curl down toward the island and score 100 per cent hits in the target area.

Then, as the Chambermaid picked up speed and began evasive action, Doscher and the navigator went forward to the flight deck.

Wasser was standing on the flight deck with one hand on the pilot’s seat and the other on the co-pilot’s, when the saga of the Chambermaid began.

About twenty-five seconds after bombs away, while Core was calling out the positions of Jap fighters which jumped the formation while flak was still breaking around it, Sergeant Milton E. Howard, the nose gunner, called and asked why his turret had stopped.

A few seconds later, Staff Sergeant George S. Shahein said that something was leaking into his turret. Whatever it was was so thick he couldn’t see a thing.

It was the first that Core knew the Chambermaid had been hit by flak. Harms, who left his place in the bombardier’s cage to investigate, found that the Chambermaid had taken a direct flak hit on the nose. Some hydraulic lines had been severed; the fluid spread quickly through the plane and leaked down into the ball turret.

“It was a hell of a mess,” Core said. “I knew then that we were in a bad way. One turret wasn’t working; the other was useless because the gunner couldn’t see anything.”

Two Japs came in on the disabled Chambermaid, one high at ten-thirty, the other at two o’clock. Core watched them both but called out the one at ten-thirty because it was closest.

The plane at two o’clock did a half roll, dropped a phosphorous bomb and came in on the Chambermaid, smoke trailing from his wing guns.

There was a dull explosion behind the co-pilot’s head.

Core saw a hole in the roof of the pilot’s compartment. Bits of aluminum and glass showered the flight deck. Core, who didn’t know that Richards had been standing behind him only inches from where the shell exploded, saw no visible damage and figured that, so far, the Chambermaid had been lucky.

The fighter at ten-thirty was still coming in, so Core kept calling him out to the gunners.

About half a minute after the shell exploded, Beatty, the co-pilot, reached around and felt his back, which had begun to hurt. His hand came away covered with blood.

Beatty turned in his seat to let Core have a look at him. The pilot saw there was a hole in his uniform with a lot of blood around it. Beatty, although nobody knew it then, had been wounded by a piece of aluminum from the plane which had been driven into his back when the shell exploded over his head. Beatty wanted to keep on flying but Core took the controls from him.

Core then discovered just how badly the Chambermaid had been hit. The throttle controlling the No. 1 engine was loose and waggled back and forth; number two throttle was jammed. Both engines were running at a speed which would use up a lot of gas. The No. 4 engine was throwing oil, and Core was sure it would be only a matter of minutes before that engine would be of no further use.

At that point, Core gave up all chances of getting home and wondered if he could set the Chambermaid down at sea on one engine; it looked as though that was all he would soon have.

Core checked the airspeed and called the flight leader, Captain Robert Valentine, to ask for protection against the Zeroes beginning to crowd the crippled plane. Four planes boxed the Chambermaid in, one above, one below and one on each wing. They adjusted their airspeed to Core’s and pooled their firepower to fight off the Japs trying to get at the cripple.

The damage to the Chambermaid, bad as it seemed to Core, was far greater than he knew.

Harms, coming back from his position in the nose of the Chambermaid to check the damage to the rest of the plane, found Staff Sergeant Ted Richards, the radio operator and top turret gunner, and Wasser, the navigator, lying on the flight deck in their own blood.

Apparently, the exploding shell had blown Wasser through the narrow opening in the pilot’s compartment and back onto the flight deck.

A freezing wind whipped through the plane and, where the top turret had been, there was now a great round hole. A second shell had exploded in the turret, blowing the dome out into the slipstream, where it careened back and tore a hole in the leading edge of the right vertical stabilizer.

Both men were in a bad way. Forty-three pieces of shrapnel from the shell which had exploded near the co-pilot had gone into Wasser’s right arm and shoulder, and a burst of machine-gun bullets from the same Jap had also hit him. Three bullets had gone through the right hand, two through his shoulders.

That Richards was even still alive was something of a miracle, since the shell which blew out his turret exploded only about three feet from his head. He was bleeding badly from his face. His windpipe was severed. His left knee, right leg, neck, and shoulders were punctured with bits of glass and shrapnel.

Harms pulled Wasser to his feet and half-carried him along the catwalk, a steel beam about a foot wide which runs over the bomb bay. Harms was afraid that Wasser would slip from his grasp and fall into the bomb bay. Although the doors were closed, Harms knew they might not support Wasser’s weight if he fell.

It was a slow, agonizing journey made all the more dangerous by the hydraulic fluid which oozed along the catwalk and made it as slippery and untenable as a cake of ice. Harms got Wasser safely over the catwalk and laid him down in the waist. He pulled the leather sleeve out of Wasser’s flying jacket, tied a tourniquet around his arm and sprinkled his other wounds with sulpha.

The waist gunner and engineer, Staff Sergeant Michael Verescak, made his way forward to Richards, lying on the flight deck. Verescak gave Richards an injection of morphine and began bandaging his wounds.

Most of the crew of the Chambermaid was now assembled in the waist. The ball turret gunners, their weapons useless anyhow, were helping with the wounded. Lieutenant Doscher made his way over the catwalk, borrowed a bottle of iodine, took down his pants and, with Shahein’s help, dressed a deep wound in his right thigh caused by the shell that had exploded in the flight deck.

Harms, bandaging Wasser in the waist of the plane, saw Verescak run and slide over the slippery catwalk to the waist gun. He began firing.

Surely, Harms thought, this was the end. Verescak’s lone gun couldn’t beat off the Zeroes.

Actually, there were no Zeroes. The Chambermaid had finally passed out of fighter range and the Japs had turned for home. Verescak, bandaging Richards on the flight deck, got furious at what the Japs had done and was firing the waist gun in sheer rage.

Beatty, the co-pilot, presently came back into the waist to have his wounds dressed, and Core called back over the intercom for Staff Sergeant Robert E. Martin, the left waist gunner.

Martin, a slight, freckled youngster who looked more like a Boy Scout troop leader than the gunner of a combat bomber, was —like many enlisted aircrew members— a frustrated pilot. Two thirds of the way through Cadet Training, when he had piled up 150 hours of flying, Martin was rejected for “lack of flying ability.”

Back in the States, during transitional training, Core had allowed Martin to sit in occasionally as co-pilot with the idea that someday his ability might come in handy. This, surely, was the day.

Martin moved into Beatty’s seat, took the control column and began flying the Chambermaid with Core.

The pilot, greatly relieved to know that the Chambermaid was finally out of Jap fighter range, turned his full attention to the disabled engines.

He now had full control only over the No. 3 engine; and although its cowling was peppered with shrapnel, it was functioning smoothly. He had no throttle control over the No. 1 and 2 engines. Every few minutes, No. 2 would “hunt” or go wild, speed up, and cause the plane to vibrate wildly until it threatened to fall apart in the air. Engine No. 4 was throwing oil and smoking badly.

Every hour, just about on the hour, the No. 4 engine would burst into flames, burn for about thirty seconds until it consumed the surface oil and then go out.

Every rule Core knew about mechanics said that the engine should have burned out right after the oil went. But it kept on smoking and burning and running without oil hour after hour.

Unless Core could find a way to cut down the propeller speeds on the No. 1 and 2 engines, the Chambermaid would consume her last ounce of gas far short of Saipan.

Core tried the No. 1 engine first. After a lot of experimenting, he found that he could slow down the prop by feeding it air from the turbo-charger, an instrument normally used to feed oxygen to engines in the thin air of the stratosphere.

Core slowed down the No. 2 engine by a totally unorthodox use of the feathering button, a device usually employed to hold the propeller of a useless engine motionless against the wing by changing its pitch. Without the feathering device, the propeller windmills and can tear itself out of the nacelle.

Core would hit the feathering button of the No. 2 engine, wait until the propeller slowed down almost to a stall and then pull out the button. He kept changing the setting of the supercharger to keep the port and starboard engines running somewhere near the same speed.

Every little while, Core turned in his seat and winked at Richards, lying on the flight deck behind the pilot’s seat. Richards, unable to speak because of his severed wind pipe, grinned and winked back.

While Core kept manipulating the engines, Martin steered the bomber along the heading for Saipan. The Chambermaid lumbered along at 140 miles an hour, fifteen miles above the speed at which a Liberator stalls out.

Despite Core’s efforts, the engines were eating gas at an alarming rate. Worse, the Chambermaid was settling toward the water at the rate of 40 feet per minute.

The unwounded members of the crew in the waist began throwing things out the windows. The machine guns were taken from their mounts and thrown into the sea. Ammunition belts, flak suits, and extra radio coils were tossed out. They tried to unbolt the lower gun turret but the wrench they were using, the only one aboard, got slippery from hydraulic fluid and fell overboard.

Except for Harms and Shahein, who remained in the waist to take care of Wasser, the rest of the crew made its way forward to the flight deck to help balance the plane, which was moving through the rough weather and bucking violently.

Core, up to this time, had been concerned only with keeping the Chambermaid in the air and had given no thought to the possibility of reaching Saipan; the chances had seemed too remote.

Now, as the hours passed, Core began to hope that the Chambermaid might hold together and the fuel might last until they reached the island.

The new hope gave Core something else to worry about. With the hydraulic system out of commission, the brakeless plane would overrun the landing strip and crash. Bailing out over Saipan, the safer course however risky it was, was out of the question because of the wounded men aboard.

Verescak worked his way to the Chambermaid’s bashed-in nose and tried to repair the damaged hydraulic lines. He patched up one line, taped a hole in another and poured hydraulic from the emergency tanks into the system. The taped hole opened and most of the fluid was lost.

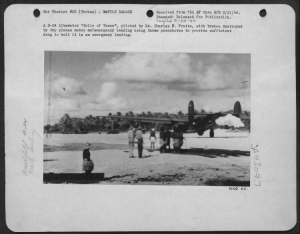

Core called the flight leader, Captain Valentine, and told him his predicament. Valentine remembered the parachute brakes used first by the Texas Belle [2] at Tarawa and told Core to rig three chutes in the same way.

Five hours from the moment the Chambermaid was hit over Iwo Jima, Saipan appeared on the horizon.

It was growing dusk as the Chambermaid and her four escorts made landfall. Three of the planes left the formation to land at other fields; Valentine stayed with the Chambermaid and led it toward the airstrip.

Core couldn’t get through to the control tower, so communications between the Chambermaid and the ground had to be carried on through Valentine.

While Sergeant Martin flew the crippled bomber, Core went back into the plane to prepare it for the landing.

Three parachutes were rigged, one at each waist mount and one from the tail gunner’s position. Corporal Robert C. Harriff, the tail gunner, volunteered for the suicidal task of remaining in the tail— the most dangerous spot in the bomber during a bad landing— to pop the pilot chute on signal from Core.

With the hydraulic system useless, the Chambermaid’s heavy landing gear could only be lowered by an emergency hand crank. Verescak tested the cables by tugging at them with his full weight. They seemed to hold, so Core ordered the wheels cranked down.

The right wheel went down and locked. The cable controlling the left wheel snapped; the wheel remained locked in its well.

To the wounded and unwounded men aboard the Chambermaid, who had come six hundred impossible miles and five endless hours to within a few thousand feet and less than five minutes of safety, that was the end. They wanted to cry.

It would have been difficult enough to land the Chambermaid without brakes and with most of her instruments shot out. It would have been dangerous, but still possible, to slide the thirty-ton bomber in on its belly.

But now the Chambermaid faced the most impossible landing of all: one wheel up and one wheel down. The very best Core could hope for was a bad crash.

Verescak made one last attempt to repair the severed hydraulic lines. With a pair of pliers, he tried to pinch the tubing together at the main break. The hole was too big. Then he held his hand over the break while Core tried to get the wheel down. The fluid squirted through Verescak’s fingers.

Core went back to the controls and tried to dislodge the wheel by slamming and skidding the Chambermaid around in the air. It was no use.

Verescak and Shahein, working in the cramped space of the nose, managed to kick the nose wheel down into place. It couldn’t help much, but it might help Core to keep the plane from falling off its supporting wheel onto the wing; a ground loop would probably finish the Chambermaid and everybody aboard.

Core called Valentine and told him the new development aboard the Chambermaid. Valentine could do nothing but call the tower and order the right side of the runway cleared for a crash landing.

Core ordered everybody back into the waist except Sergeant Martin, who remained as co-pilot.

Verescak and Shahein carried Richards from the flight deck back to the catwalk. Verescak led the way across, holding Richards’ left leg straight as he could. Richards hopped and slid along the beam on his right leg while Shahein held him from behind. They got Richards into the waist and laid him down beside Wasser.

It seemed to take a long time to clear the runway. The double row of field lights marking the strip grew sharper and brighter as darkness settled. Core could make out the dim outlines of planes being towed across to the left side of the runway.

Ambulances and a crash truck came out from under the control tower, moved down the runway and waited with motors running.

The unwounded men aboard the Chambermaid got down on the floor and arranged themselves around Richards, Wasser, Beatty, and Dorcher, facing the wounded so their own bodies would help cushion them against the shock of the crash.

Two men braced themselves near the parachutes attached to the gun mounts.

Core and Martin strapped themselves in.

Then Core called Valentine and said simply, “Coming in!”

The Chambermaid came in high and straight. Martin pumped the flaps down by hand. Core switched on the landing lights; one of them had been shot out, too. Martin cut the No. 1 engine. Core braced his full weight against the left rudder.

The Chambermaid touched the ground.

It hit the runway at 105 miles an hour and swerved sharply to the right. Martin cut the power with the master switch. The chutes popped open and slowed the plane a little but failed to halt its wild plunge over the field lights and off the runway.

The Chambermaid teetered level for a moment and then lost its balance. The right wing dug into the ground and the massive propeller of the No. 1 engine snapped off and skidded down the runway trailing a shower of sparks.

The wild plane plowed onward toward a jeep trailer fitted with a rack of floodlights. There was a slight jar and the floodlights showered into the air.

Core saw the whole left side of the instrument panel caving in toward him. He got two thirds of the way out of his seat and was held there by his safety belt.

With a great, grinding roar, the Chambermaid plowed a hundred yards through dirt and gravel, crashed sideways into a revetment and stopped.

And then everything was quiet.

There was no sound in the crumpled and broken mass of steel and aluminum. Nothing but the faint, far away hiss of flames eating at an engine.

Core and Martin sat motionless in the wreckage of the cockpit. They were trying to make themselves believe that it was all over, that they were on the ground and still alive.

Core thought vaguely of the fire in the No. 1 engine. He decided it would die out.

Core and Martin unstrapped themselves, broke a window and squirmed out of the wreckage. They ran around to the waist of the plane.

Some of the men were already out of the wreckage. The others were crawling through great gaps in the fuselage.

Harms began to count the crew and suddenly remembered he hadn’t seen Harriff, the tail gunner. He ran toward the back of the plane. There was something hanging from the gun mount; it looked like a man’s body. It turned out to be the parachute Harriff had opened.

It was a couple of minutes before Harms found the tail gunner. He had jumped from the plane and was wandering around dazedly in the crowd which had gathered to see the Chambermaid come in.

Every man was cut or bruised in the crash, but nobody was seriously hurt. The wounded men were not much worse off than they had been before the landing.

The ambulances came up and the medics started putting the wounded men on stretchers.

Beatty, the co-pilot, lying on a stretcher and waiting to be lifted into an ambulance, saw the Chambermaid’s crew chief in the crowd.

Beatty felt sorry for the crew chief. He had taken care of the Chambermaid before and after every one of her missions.

There was nothing the crew chief could do now to fix the Chambermaid. Her fuselage was broken in half behind the bomb bay. Her nose was buckled in, and her wings were all but torn off. Parts of her were strewn along the path she had plowed up coming in.

As Beatty was being lifted into the ambulance, he saw the crew chief walk slowly toward the wreckage and called out after him:

“I’m sorry we wrecked your plane, Sergeant.”

____________________________________________

Footnotes

[1] Misnomer for Belle of Texas, a B-24J serving with the 42nd Bomb Squadron, 11th Bomb Group. (ed.)

[2] Photo of Belle of Texas showing the parachutes used for improvised air brakes. (ed.)

5