Editor’s note: The following is extracted from History, by Bernadotte Perrin (published 1912).

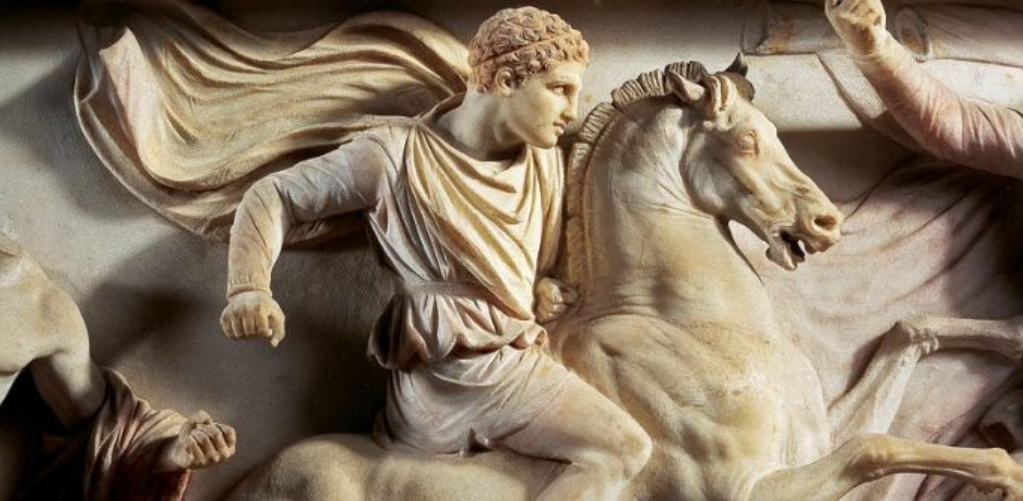

But while Ephorus and Theopompus were yet writing, a new personage had entered the ancient world, who, in an amazingly short time, completely transformed it. Alexander, the son of Philip of Macedon, in a meteoric career of less than twenty years, surpassed in actual and palpable achievements all that the glowing imaginations of poets and prose romancers had devised for men to admire and wonder at. Once more, as in the sixth and fifth centuries, history became stranger and more fascinating than romance had been, and led the way to still bolder flights of fancy in a new romance. The wonders of India and the extreme East now eclipsed what had once been wonderful in Persia and the nearer East, as that had eclipsed the wonders of the heroic age, and Greek fancy grew by what it fed upon. On Alexander himself the marvelous in his career seems to have produced some spell, nor was it wholly from political reasons that he came to think himself, and to wish others to think him, a god. On the smaller spirits in his retinue the marvelous in their experience produced the effect of an apparent incapacity to state a common fact as such. There were sober heads among them, it is true – a Callisthenes, an Aristobulus, a Ptolemy, a Nearchus, and from them we know the truth about Alexander’s campaigns, but only because the Graeco-Roman Arrian, four centuries later, recurred to their testimonies. Their contemporaries would none of them, but preferred the extravagant exaggerations of Onesicritus, or the wilder flights of fancy which marked the current and popular oral tradition. For Alexander was accompanied from the first by a traveling literary court of poets, philosophers, and historians, and each of the momentous steps in his progress was celebrated by athletic and literary festivals to which the greatest artists of Greece were summoned. His frequent exchange of worn-out soldiers for fresher and younger ones also kept up a constant line of oral communication between his deeds and the riotous fancy of the stay-at-homes. But so rapid and dazzling were his achievements that contemporary imagination could not keep pace with them. Especially after the conqueror had vanished wholly from the view of the Hellenic world during the three years of his Indian expedition did the Hellenic imagination revel in the historical and mythological possibilities of the case. Heracles and Dionysus were not only imitated, but outdone, by this new god of conquest. Moreover, the mental energies of the Ionian Hellenes, deflected from political life by the Macedonian supremacy, found vent more than ever in literary expression. Old forms of expression were cultivated into decadence, and new forms were devised. The literature of pure romance began. There was, however, no such recognized channel, as yet, for the flow of pure fancy and invention in prose as was afforded later by professedly fictitious narrative – the romance and the novel. These were yet to be set apart as distinct forms of literary art. Fancy and invention therefore found play in the realm of what should have been historical narrative. And so it came to pass that before Alexander had been dead thirty years, a mass of legend and romance had grown up around the main authenticated facts of his career. This mass has been varied in its rhetorical treatment rather than sensibly increased by the romantic invention which has ever since been busy with that career, down through the middle ages, and into the times of our Old English literature.

This romantic version of Alexander’s career, with its firm basis of authenticated facts and its luxuriant envelope of legend and fictitious anecdote, vague with all the vagueness of popular tradition, found its Herodotus in Cleitarchus of Colophon, a contemporary, but not a companion of Alexander. He was the son of Deinon of Colophon, who was an imaginative historian of eastern realms, and a pupil of Stilpo of Megara, a rhetorician and philosopher celebrated above all for grace and cleverness of literary style. His history of Alexander, highly rhetorical, and full of the wildest flights of fancy, became the standard, as the history of Greece down to Alexander by Ephorus was standard. It forestalled the sober testimonies of the four sober companions of Alexander to whom Arrian, four centuries later, led the world back, for, at the time, it met the world’s demands. We know Cleitarchus chiefly through late Roman compilers like Diodorus Siculus, Justin, and Quintus Curtius, but we understand perfectly why the author of the treatise “On the Sublime” calls him empty and bombastic, and why even Plutarch discredits him. “At this time,” says Plutarch (Alexander, xlvi), “most writers say that the Queen of the Amazons paid a visit to Alexander, of whom are Cleitarchus and Onesicritus. But Ptolemy and Aristobulus say that this is fiction.” Cleitarchus therefore followed Onesicritus in preference to Ptolemy and Aristobulus, and of Onesicritus, thanks to Lucian, we can form a sure estimate.

Just after the great Indian campaign against Porus and his elephants, and while Alexander and his army were descending this Hydaspes in their extemporized flotilla, a certain historian, so Lucian tells us (Quom. hist. scrib., xii), bent on flattery, read aloud to Alexander what he had written about a fierce duel between Alexander in person and the gigantic Porus mounted on an elephant. Now we have in Arrian what is substantially Ptolemy’s account of the battle with Porus, and there neither was nor could have been at any time during the battle a duel between Porus and Alexander. But just as at Issus and Arbela romantic historians insist, against all the facts, on bringing Darius and Alexander into personal combat, so in the struggle with Porus the flattering historian thought that the two leaders must have their Homeric duel. Here we can put our finger on Alexander-romance in the very making. As the historian read aloud to Alexander, thinking to gratify the king by inventing the most fabulous exploits for him, Alexander caught away the writing from him and hurled it into the river, saying, “I ought to do the same to you, my man, for fighting such a duel and killing such elephants for me with a single javelin.” This historian, as we learn from another passage in the same work of Lucian (chap. xl), was Onesicritus, the Munchausen of Alexander’s companions. And it is in all probability his version of the visit of the Amazonian queen to Alexander which Arrian mentions as “reported” (vii. 13, 3), only to remark: “but this is recorded neither by Ptolemy nor Aristobulus, nor by anyone else capable of testimony in such matters. And personally, I do not believe that the race of Amazons was surviving at that time either, or Xenophon would have mentioned them.” This reputed visit of the queen of the Amazons to Alexander may serve as a fair specimen of the countless bold inventions which the history of Cleitarchus adopted.

With Cleitarchus and his history of Alexander, which was for a long time canonical, we may well close this brief survey of Greek historiography. In the century after Alexander, Duris of Samos was led to write a history of Greece in which, judging from the fragments of it which have come down to us, startling effects were sought and gained by resort to coarse and realistic sensationalism, a new manifestation of the Homeric and Herodotean desire to please rather than to instruct, but not one which became dominant. With Timaeus of Tauromenium and with Polybius the Roman spirit manifests itself, and historiography ceases to be distinctively Hellenic. “Distinctively Greek historiography,” to repeat from the opening paragraph of the lecture, “may be said to end with the historians of Alexander’s career. And it ends, as it begins, with a triumph of fancy and invention over fact and re-presentation. In the middle ground, in Thucydides and Xenophon, the desire to inform is duly enthroned beside the desire to please; but the Greek hearer or reader usually preferred a flight of the imagination to a statement of the truth; and the sovereign names among the Greeks themselves were Homer, Herodotus, Ephorus, and Cleitarchus, names representing a body of highly imaginative and mainly fictitious poetry, and a body of highly imaginative and largely fictitious prose.” And our survey has itself made plain, without further definition, the permanent value of this body of historical literature. It has such value if it does no more than illustrate, by two splendid specimens in the works of Herodotus and Thucydides, artistic success in writing history that charms, and artistic success in writing history that edifies. Imagination a good historian must always have, creative imagination even, especially in the problems of psychological reconstruction, wherein the best modern historians make most advance upon Thucydides; and rhetorical skill a good historian must have, in order to win readers for the truths which he has laboriously elicited from complex testimonies. But the imagination must not become inventive purely, nor must the inventions of imagination or the attractions of rhetoric ever become the main object of the historian. How easy to illustrate from the works of modern historians with which we are all familiar! How easy, also, to follow Professor Bury when he says, “Within the limits of the task he attempted Thucydides was a master in the craft of investigating contemporary events, and it may be doubted whether, within those limits, the nineteenth century would have much to teach him.”