Editor’s note: The following is extracted from History, by Bernadotte Perrin (published 1912).

When Alexander the Great crossed into Asia on his long career of conquest, he took a trained historian with him. He was conscious of making history of which men after him would be glad to read. But many centuries of Greek history found no recording historians. They would have been interesting to us, who are so absorbed in origins and developments, in causality and evolution, in “historical relativity,” that we begrudge oblivion any data whatsoever. But they were not interesting enough to contemporary Greeks to find chroniclers. Speaking broadly, it always required some great spectacular struggle – the Trojan War, the Persian Wars, the Peloponnesian War, the duel between Sparta and Thebes, the Hellenic conquest of Asia – to elicit, as it were, a great historian; and Homer, Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, and Cleitarchus are the canonical names corresponding to these spectacular struggles. There are others, of course, but these tower above all, and the others are usually little more than names to us. Polybius also was moved to compose his great work by the transcendent struggle between Rome and Carthage; but Polybius, though writing in Greek, had become, by long residence in Rome, and intimate association with leading Romans, more than half Roman in spirit. Not forgetting the sensational Duris of Samos, nor the learned antiquarian Timaeus of Tauromenium, we may say that distinctively Greek historiography ends with the historians of Alexander’s career. And it ends, as it begins, with a triumph of fancy and invention over fact and re-presentation. In the middle ground, in Thucydides and Xenophon, the desire to inform is duly enthroned beside the desire to please; but the Greek hearer or reader usually preferred a flight of the imagination to a statement of the truth, and the sovereign names among the Greeks themselves were Homer, Herodotus, Ephorus, and Cleitarchus, names representing a body of highly imaginative and mainly fictitious poetry, and a body of highly imaginative and largely fictitious prose.

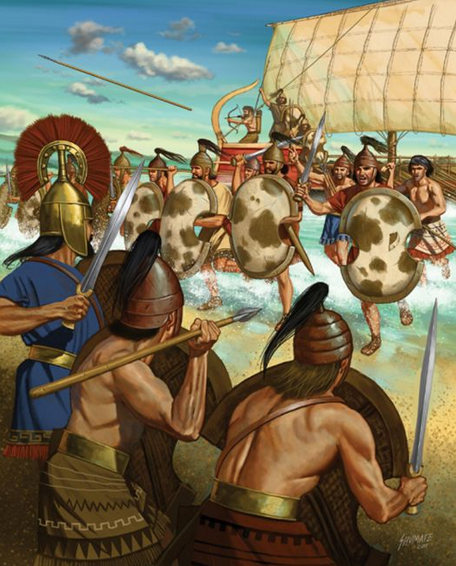

Well on into that greatest century of Greek life and thought which began five hundred years before Christ, the Homeric poems, and especially the Iliad and Odyssey, were regarded by most Greeks as authentic history. Achilles, Agamemnon, Andromache, Odysseus, Laertes, and Penelope had actually and in very person fought, ruled, suffered, wandered, grieved, and been steadfast to the end, even as they are there described. Thersites had railed at the Atreidae, Diomedes had wounded Aphrodite, Hector had slain Patroclus, Achilles had slain Hector, and aged Priam had ransomed the dead body of his son, even as we now read in the Iliad. Ilios, the proud city of the Troad, commanding the Hellespont and the Euxine Sea, had been captured and sacked by the leagued hosts of the Lord of Mycenae, a city which dominated Peloponnesus, and the hosts had met with various dooms on their various ways home. All this had long been history to the Greeks, just as the book of Genesis has long been history to Christian peoples. Skepticism, doubt, and denial met with the same scornful reproaches in the first case which they have evoked in the second. We now know – at least Professor Murray, and those who think approximately as he does, know – that the Iliad and Odyssey are traditional race-poems, slowly evolved through the centuries which saw tribes of hardy Northerners sweep gradually down into the Aegean basin and appropriate by conquest and assimilation the rich culture existing there. The ruins which amaze the discoverer at Troy, Cnossus, Mycenae, and Orchomenus speak impressively of the power and splendor of that submerged culture.

The invaders were a song-folk. They sang because they had to sing. They sang of the achievements and adventures of their gods and heroes. One generation of them would become heroes and demigods to the next generation, and that generation to the next, and each sang of the prowess of the past. A traditional poesy arose, shot through with “a fiery intensity of imagination,” and served by a language “more gorgeous that Milton’s, yet as simple and direct as that of Burns.” Into the crucible of this traditional poesy were poured for centuries the migrations and conquests of tribes; the oversea expeditions of thalassocratic cities; racial myths and legends. Into the crucible went also the absolute fictions of a powerfully creative imagination laboring at high pressure to supply a keen demand. The centre of poetic activity shifted from the European to the Asiatic side of the Aegean, and Aeolians to Ionians. Guilds of poets flourished in the chief Ionian cities, who slowly fashioned the molten material from the great crucible of epic poesy into the definite structures of the Iliad and Odyssey, and then went on to complete in later compositions the epic cycle which the elder epics logically and chronologically demanded. If material was lacking, the gap was filled by fresh creation until the cycle was complete, and then the epic impulse slowly died. These later epics, ascribed to individual and historical poets, have perished. But the central poems around which they had been made to cluster assumed canonical form for use in national religious festivals, and finally passed, with all the other rich fruits of Ionian culture, across the sea again, flying before the conquering power of Persia, to Ionian Athens. There they found the patronage of a rich tyrant’s brilliant court, and there they were learnedly and skilfully edited into substantially the shape in which they have come down to us. At national religious festivals they were recognized as national religious poems, and as national history. The mythical, legendary, and purely fictitious accretions in them were seldom distinguished from the genuinely historical nuclei. They were thought to be the work of one man, a divine Homer. And yet they actually “represented not the independent invention of any one man, but the ever moving tradition of many generations of men. They are wholes built up out of a great mass of legendary poetry, re-treated and re-created by successive poets in successive ages, the histories knitted together and made more interesting to an audience by the instinctive processes of fiction.”

When ‘Omer smote ‘is bloomin’ lyre,

He’d ‘eard men sing by land and sea;

An’ what he thought ‘e might require,

‘E went and took – the same as me!

Multiply Kipling’s blithe “ ‘Omer” many times, and distribute him through five or six centuries, and you have the Homer of Professor Murray, my Homer, your Homer – perhaps.

But besides the Homeric poems, Ionia also produced a scientific spirit, which looked out on life observantly, and drew inferences from it which were fatal to a belief in the truth of those poems. It is characteristic of this period of scientific inquiry, as Professor Bury has remarked, that sages take the place of heroes in popular fancy, or, at least, take a place beside them, and we have the myths of the Seven Wise Men. Great historical personages also loom up from the near past, like Polycrates, Periander, and Croesus, about whom fiction weaves its fascinating web. The advance of the Persian power from the Orient to the Aegean, and of its spectacular conquests of the Lydian dynasty first and then of the Asiatic Greeks, made near and current events even more attractive to the Greek fancy than what were supposed to be the real events of the Homeric poems, or what the new scientific spirit denounced as the falsehoods of those poems. Truth, for a season at least, became stranger and more fascinating than fiction. The geography and peoples of the Orient were brought home to the Greek fancy by Hecataeus; the story of that all-conquering folk, the Persians, by Xanthus the Lydian and Dionysius of Miletus. That story soon included the invasions of Europe by Darius and Xerxes, and the splendor of the story, even without the exaggerations which the lively Greek fancy was sure to give it, made the undertakings and achievements of the heroic age far less impressive than they had been. In time, Thucydides could allude to them with something of scorn. To put it briefly, the new critical spirit brought the truth of the Greeks’ Ancient History, as it was presented in the Homeric poems, into doubt and disbelief, and the Modern History of the Greeks became so fascinating that it absorbed the active imagination of the race.

(Continue to next chapter)