Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Noble Lives and Noble Deeds, by Edward A. Horton (published 1910).

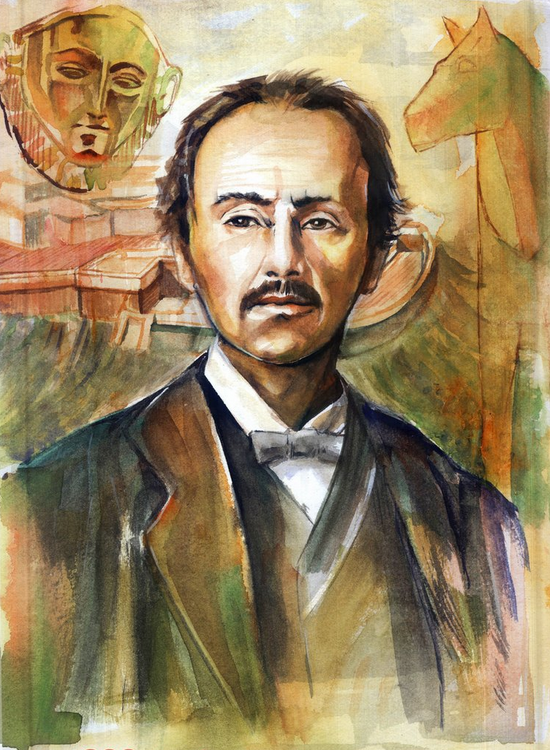

Heinrich Schliemann was born at Kalkorst, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, in 1822. He was the son of a poor Lutheran clergyman, and was intended for a university career. But this plan could not be carried out. His mother died when he was nine years old. As the family numbered seven children, their education became a difficult matter, and Heinrich was sent to his uncle, with whom he studied a year. When he was fourteen, he was apprenticed to a small grocer, where his duties consisted of selling across the counter herrings, butter, milk, salt, coffee, sugar, oil, tallow-candles, etc., sweeping the shop, and doing many other distasteful duties. He had very little time for the cultivation of his mind. Dr. Schliemann remembers a characteristic little event that occurred at this time.

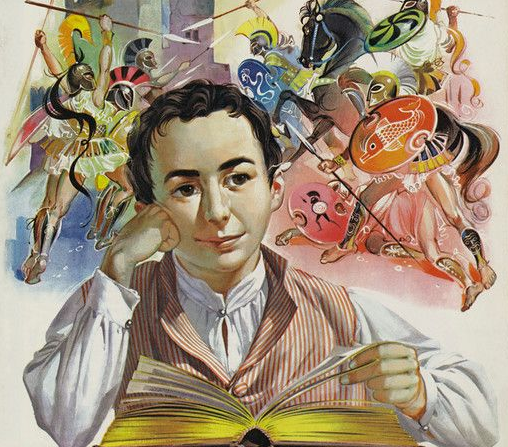

One evening there came to the shop a miller’s man who had been born in better circumstances and educated at a gymnasium, but who had been unfortunate and come down in the world; yet he had not forgotten his Homer. “That evening,” says Dr. Schliemann, “he recited to us about a hundred lines of the poet, observing the rhythmic cadence of the verses. Although I did not understand a syllable, the melodious sound of the words made a deep impression upon me, and I wept bitter tears over my unhappy fate. Three times over did I get him to repeat to me those divine verses, rewarding his trouble with the few pence that made up my whole wealth From that moment I never ceased to pray to God that by his grace I might yet have the happiness of learning Greek.”

After five years in this grocery-store, he overstrained himself and had to give up his work. In his delicate condition it was difficult to find another place. In despair, he bound himself as a cabin boy, sold his only coat to buy a blanket for the voyage, and set sail for Venezuela. The ship was wrecked on the Dutch coast. After drifting for nine hours in a little boat he was picked up and taken to Holland. Here he decided to remain, and his first year was spent as an office-boy in a warehouse. In this capacity he had to run errands and carry letters to and from the post. But he took advantage of the perfect mental leisure to carry on his education. In his own words: “I never went on my errands, even in the rain, without having my book in my hand and learning something by heart. I never waited at the post-office without reading or repeating a passage in my mind.”

He was desirous of learning Russian, and as no teacher of this language was to be found in the town, he learned by heart the Russian translation of Telemachus. He hired, for four francs a week, a poor Jew to whom he repeated this poem evening after evening. The Jew could endure it; but Dr. Schliemann’s fellow lodgers, who had to hear everything through the thin board partitions, did not feel themselves equally bound to endurance; so the enthusiastic youth had to change his lodgings twice during this educational period.

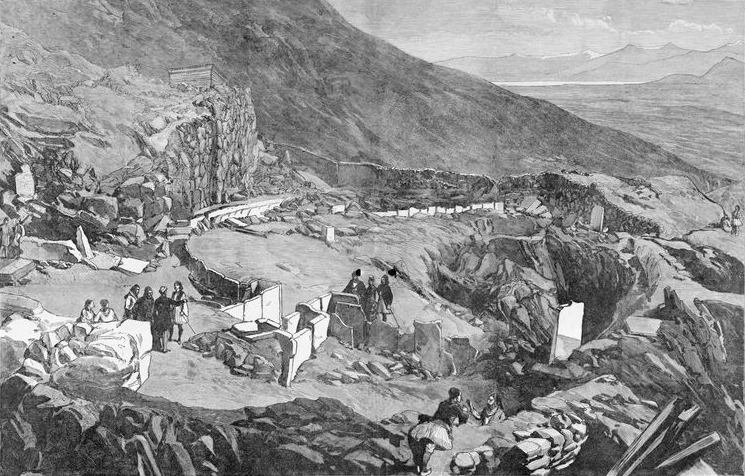

His employers now sent him to St. Petersburg as their agent. He became an American citizen in California in 1850. Matters prospered with him in a business way, so that in 1858 Dr. Schliemann believed he had made a sufficient fortune, and could now devote himself to his favorite study of archaeology. This meant the learning of some more languages, permission to be obtained from the Turkish Government, and very many preliminary difficulties which had to be overcome before the excavations could be made which were in his plans. The beginnings of this work resulted in great disappointment. What was disclosed in digging was not satisfactory. Then the work was carried on at bad times, when the weather was bitter cold; but his enthusiasm kept him warm.

The story of Dr. Schliemann’s career from this time on is full of the same trait which has marked his previous efforts. The excavations at Mycenae and Troy, and at the various spots in Greece, were conducted under the pressure of severe obstacles, and nothing but an undaunted persistence carried him through. What he accomplished is not for us to state here in detail, but the spade that he used brought to light some of the richest revelations from a buried past. Many theories which he put out and found ridiculed were proven true; and through the thick and thin of all the perplexities and opposition which he met, this great quality of his character served to make him victor.

Dr. Schliemann had said that he would only marry a Greek woman who knew her Homer by heart, and he carried out his intention, his wife being a finely educated Greek lady. He built a fine palace at Athens, where he made his permanent residence. The lower floor is a museum for his findings in the buried cities.

One of his curious ideas was to give to each of his household, and to even the transient guests, Homeric names. His children were called Andromache and Agamemnon. In the latter part of his life he was afflicted with deafness; and it was because of a cold contracted after a surgical operation upon his ears that his death occurred, at Naples, Dec. 26, 1890, and his valuable life so suddenly closed.