Editor’s note: The following account of the Second Battle of Corinth is extracted from Recollections of Thomas D. Duncan, A Confederate Soldier (published 1922). All spelling in the original.

The command of General Forrest was not in the battle of Corinth, as it occurred while we were in Kentucky; but because of the sentiment that attaches to the place as my home I desire to record here the substance of a description given me by a kinsman of the Second Texas who was in the battle.

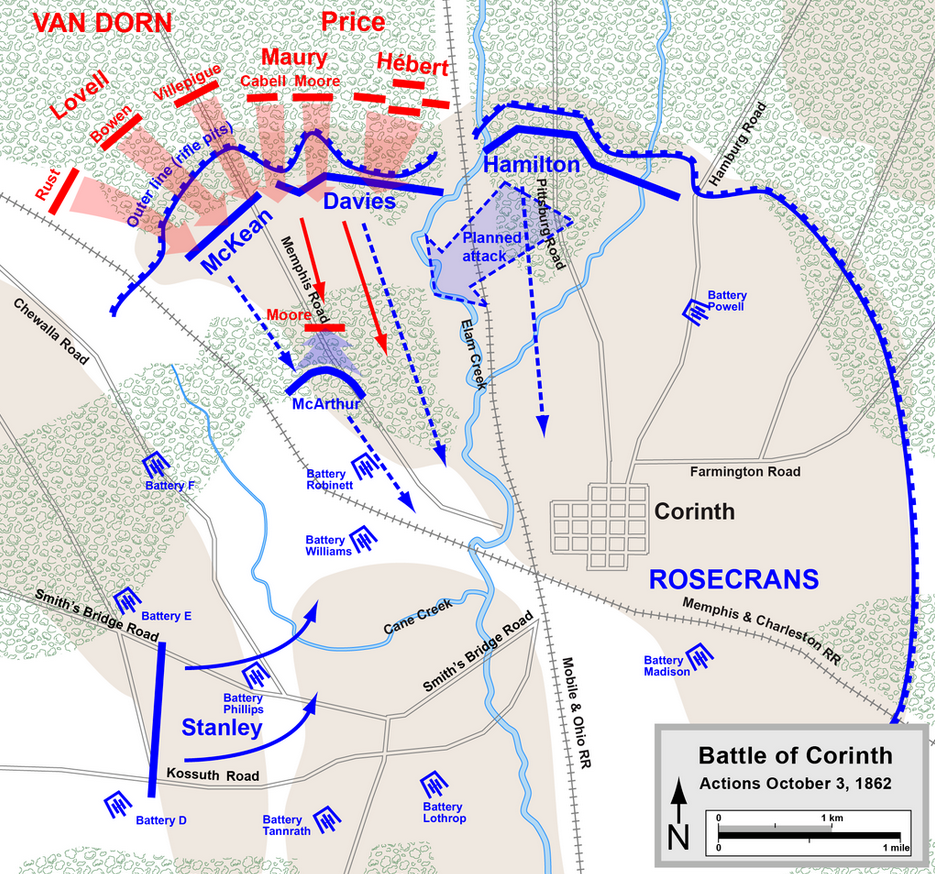

After the battle of Iuka, on September 19 and 20, 1862, the commands of General Price and General Van Dorn were united; and these two commanders resolved to attack Corinth, then occupied by the Union Army under General Rosecrans.

Under the supreme command of General Van Dorn, the Confederate Army left Chewalla, a railroad station eight miles west of Corinth, on the morning of October 3, 1862.

About ten o’clock in the morning the order to attack was given, and the command moved forward cautiously, with its skirmish line deployed in front. In a short time the skirmishers of the Second Texas became engaged with skirmishers of the enemy, and the Forty-Second Alabama Regiment, coming up during the engagement, mistook the Texans for a command of the enemy, and fired upon them, killing Lieutenant Haynes, of Company E., and six private soldiers.

The engagement soon became general. The enemy, however, retreated and fell back beyond the old Confederate breastworks, the same that I had helped to locate before the evacuation of Corinth. As our line advanced, we discovered that the Union Army was making a stand at an entrenched camp, which was strongly fortified. Their resistance was stubborn, but we drove them from their strong position. They did not retire a great distance before making another stand, seemingly with greatly increased numbers. After a brief stand, they charged us. The Second Texas received the shock, and, furiously counter attacking, they cut the Union line and captured some three hundred prisoners. At this juncture several Union batteries opened a tremendous fire on the right of the Texans from an elevated position on the south side of the Memphis and Charleston (now Southern) Railroad. The Second Texas was ordered to charge the batteries. Colonel Rodgers saw that they had been discovered by a brigade of infantry, and asked for reënforcements. Johnson’s and Dockery’s Arkansas Regiments of Cabell’s Brigade were sent, and the three regiments charged, driving back the infantry and capturing three batteries of light artillery.

We next found the stubborn enemy entrenched in a camp on an elevation between two prongs of a creek, where fresh troops had already been massed. Here was presented the most determined stand we had met with during the day. After hard fighting, with heavy losses on both sides, the Union troops were finally driven from this position at the point of the bayonet. The Union officers tried gallantly to stem the tide, General Ogelsby and General Hackelman being desperately wounded in a vain effort to rally their beaten soldiers. In this camp we found bread, butter, cheese, crackers, and other food in abundance, and, while enjoying a short rest, partook of the enemy’s unwilling hospitality during his enforced absence—the first food we had tasted that day.

When driven from this position, the enemy fled precipitately to the protection of the inner fortifications at Corinth.

About sunset the exhausted Confederates, with empty cartridge boxes, halted within about a half mile of Corinth and very near the inner fortifications. The loss in our regiment was very heavy. Among the wounded were Lieut. A. K. Leigh and Halbert Rodgers, the youthful son of the colonel who, during the day, had handled his regiment with consummate skill, being with it in every position of danger.

Before daylight on October 4 the Confederate artillery opened a vigorous fire on the enemy’s works, and a lively contest between the gray and blue cannon was kept up until after daylight. During the early morning there was sharp fighting on the skirmish line in front of the Second Texas, in which the Union skirmishers were driven in and their commander, Col. Joseph A. Mower, was severely wounded and captured, but again fell into the hands of his friends that evening after our retreat from Corinth.

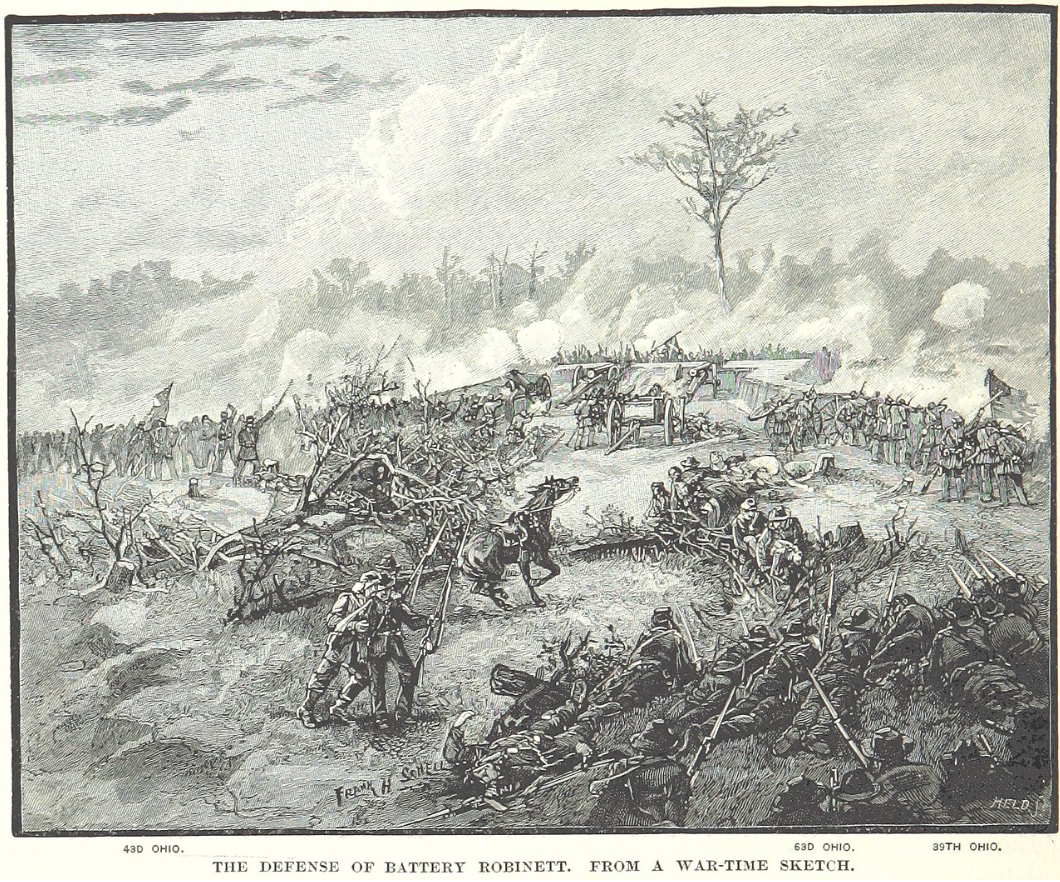

Directly in front of the Second Texas, a short distance north of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, was “Fort Robinette,” with three twenty-pound siege guns; and in “Fort Williams,” on the south side of the railroad, there were four twenty-four pounders and two eight-inch Howitzers. On the eminence between “Fort Williams” and the railroad were six guns of Battery F., U. S. Light Artillery; and on the south side of the same fort were two guns of the Second Illinois Light Artillery—all commanding the field to the westward and in positions to sweep the hillside in front of “Robinette.” In addition to these, two guns of the Wisconsin Light Artillery occupied a point just north of and very close to “Robinette,” between it and the Chewalla dirt road, and in a position to sweep the top and side of the hill in front.

These were the positions of the Union artillery, seventeen guns in all, in front of the Second Texas Regiment and commanding the ground over which that wonderful organization of fighters was about to deliver one of the most daring and desperate assaults in the history of wars.

The Union infantry was also placed advantageously for dealing destruction to the assaulting column.

The Forty-Seventh Illinois Regiment lay behind the railroad, immediately in front of “Fort Williams,” covering the hillside with their deadly Springfield rifles. The Forty-Third Ohio occupied the ground immediately behind the breastworks on the north side of “Robinette,” with its left near the fort. The Eleventh Missouri was lying down under the hill, about fifty yards in the rear of “Robinette,” with its right and left wings expanding opposite the Forty-Third and Sixty-Third Ohio, respectively. The Twenty-Seventh Ohio occupied the trenches on the right of the Sixty-Third; and the Thirty-Ninth Ohio was still further to the north, on the right of the Twenty-Seventh, with its right wing facing north, at right angles to the line of its left wing and to the Twenty-Seventh and the Sixty-Third.

The order to charge had been expected every moment since daylight; but owing to the sudden illness of General Herbert, commanding the Left Division of Price’s Corps, the initial attack had been delayed until about ten o’clock. During the interval of waiting the men were subjected to the most intense mental strain. As every trained and experienced soldier will testify, the suspense of waiting in the prelude of an onset is more trying than the actual conflict, wherein the heat of battle fevers the mind into a kind of fearless frenzy that causes it to lose the weights and measures of danger.

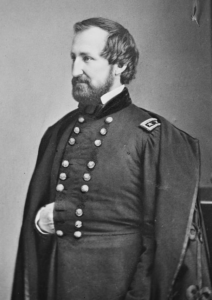

When the order to advance was given, that fine body of soldiers obeyed as unhesitatingly as if the impulse to move had been that of a single man, the different regiments being massed in five lines of two companies each. When they encountered the abatis—an obstruction of felled trees, with sharpened and interwoven branches—the formation was necessarily somewhat broken, just as the enemy’s artillery began to blast and wither the moving mass of men; but each man, though but an atom of the fiery storm, moved with a separate though strangely co-operative intelligence, advancing with remarkable rapidity toward the common objective, “Fort Robinette.” As soon as the abatis was passed, a partial restoration of the organizations took place in the very furnace of battle as the lines sprang forward with a many-voiced yell. When they reached the brow of the hill, the earth trembled under the deafening crash of the opposing artillery, while the Union infantry regiments poured a deadly enfilading fire into the right flank of the Texans. It was beyond the power of human endurance, however sublime the courage that willed it, to withstand such a shock of lead and iron, and the attackers of “Robinette” recoiled through a quivering sheet of flame. With encouraging words from the intrepid colonel, a partial reformation was effected, and the order to charge again was given. As steel on flint, a blow to the brave strikes fire in the soul; and so these smitten Texans flamed with fury as they returned to the charge. The slaughter was one-sided and terrible; and as the men in gray recoiled a second time, the fourth color bearer fell with the flag in his hand. Then it was that Colonel Rodgers seized the tattered banner and rode into the midst of his heroic band. Once more forming them into a ragged line, he asked if they were willing to follow him, and they responded with an affirmative yell. Again the order to advance was given, and the Colonel rode up the hill directly toward the fort, bearing the colors.

With a steady gaze fixed on the fort, he moderated his horse’s pace to the pace of his men. The column moved forward in double-quick time. Their ranks were ruthlessly raked with lead and iron; but the living filled the gaps left by the dead, as the bleeding remnant pressed on to the fort.

Colonel Rodgers rode into the ditch that fronted the works, followed by the head of his column; and as the others came up, they scattered around either side. The right wing of the Second Texas was met by the determined front of the Forty-Third Ohio, and a hand-to-hand conflict followed. The onset of the Texans was made with such reckless desperation that the Ohioans were put to flight, leaving one-half of their number killed or wounded on the ground, their brave colonel, J. Kirby-Smith, being among the slain.

On the north side of “Robinette” the left wing of the Second Texas came in contact with the Sixty-Third Ohio; and, after a bloody contest at close quarters, the blue column was driven back at the point of the bayonet, leaving fifty-three per cent of its number on the ground. The section of light artillery at that point made its escape to the Union rear.

While these bloody conflicts were taking place on both flanks of the fort, Colonel Rodgers climbed upon the parapet and planted the flag of his regiment in triumph at its top. The men who had followed him leaped fearlessly down inside the fort, and, with others who had crawled through the embrasures, unexpectedly engaged the cannoneers in a hand-to-hand conflict. The fight was short and fierce, and thirteen out of twenty-six men of the First U. S. Infantry who manned the guns of the fort were slain, and a number of others, including the commander, Lieutenant Robinette, were wounded.

Thus was the fort captured and silenced; but “Fort Williams” continued to pour its deadly fire into the gray, thinned ranks and into the struggling mass of gray and blue, while the Forty-Seventh Illinois, from its elevated position along the railroad, swept the parapets of “Robinette” with long-range rifles as the Confederates scaled them.

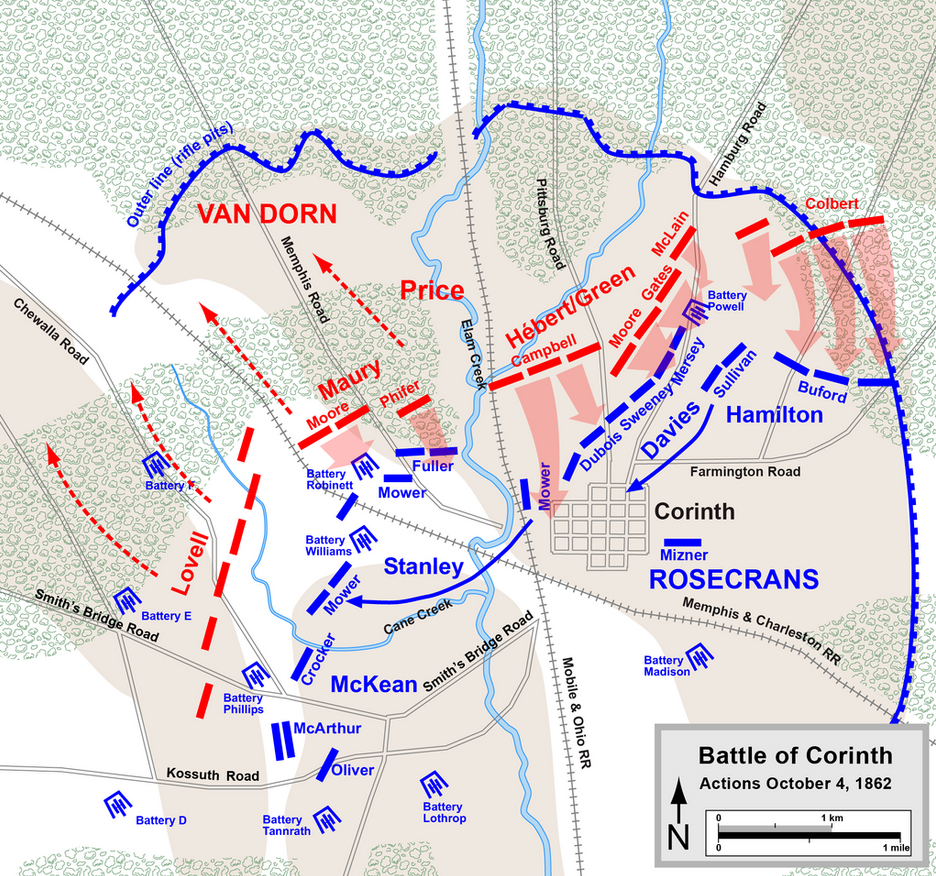

Meantime a fearful hand-to-hand fight was raging in the heart of the town—around the railroad depot, the Tishomingo Hotel, the Corinth House, and even in the yard around the headquarters of General Rosecrans, the old Duncan homestead. The fighting was furious, but the heavy reserves of fresh troops which the Union commander had massed in the central and the southwest portions of the town met the torn and half-exhausted columns of the Confederates and literally plucked victory from defeat.

The victorious reserves of the enemy marched upon “Robinette” from the town, Gen. David S. Stanley advancing from the southeast with the reformed Forty-Third Ohio and two fresh regiments.

When it was apparent to the little band of Texans in and upon the captured fort that their dearly bought victory was of no avail and that the day was lost with the repulse of the Confederates in the center of the town, Colonel Rodgers’ first thought was to save the lives of as many of his men as possible, and he waved his handkerchief from the top of the parapet, making known his desire to surrender; but the enemy either did not see him or misunderstood or mistrusted the signal, for the firing continued from both advancing columns. He then said to the men around him: “The enemy refuses to accept our surrender, and we will sell our lives as dearly as possible.”

With a calm precision, he then ordered his men to fall back into the ditch outside the fort, and there gave the order for the retreat. He climbed out of the ditch with the flag in one hand and his pistol in the other, the remnant of his shattered band clustering around him, and they slowly retreated backward as they returned the fire of the advancing and overwhelming lines of blue.

Up to this time the Eleventh Missouri Regiment had not fired a shot; but about the time this heroic retreat began, it suddenly rose from its waiting position, rushed upon and around the fort, and poured a withering fire into the retreating band of Texans, and their intrepid leader fell, pierced with eleven wounds. The flag fell across his body; and the few yet remaining of his loyal band, remembering the vows made when this flag was presented to the regiment at Houston by the ladies of Texas, seized and bore the fallen emblem away, Ben Wade, of Company I, being the man who rescued it.

By this time the whole Confederate Army was in retreat. General Villepigue’s Brigade of Lovell’s Division marched by the left flank across the Memphis and Charleston Railroad and threw its columns between the shattered ranks of Maury’s Division and the expected pursuit. The conquerors stood aghast at the combination of circumstances which had given them the victory. Enchanted by the comparative calm that followed the storm, they seemed satisfied to rest upon their laurels and forego the opportunity to follow the weary and beaten foe.

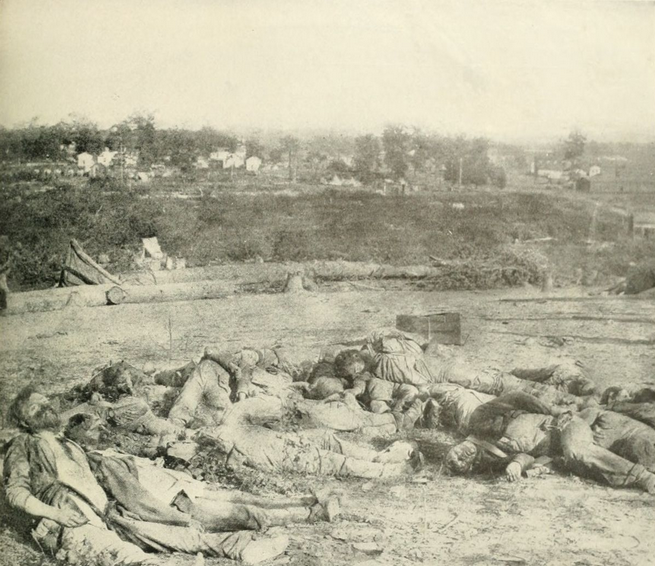

When the smoke lifted its somber veil from the sorrowful field of carnage, the face of the landscape was distorted with horror, expressed in suffering and death. But the spirit of immortal glory hovered there, for the soil of Mississippi had been sanctified by the blood of heroes, and amid the falling tears and broken hearts of the South and of the North the Muse of History was gathering from the broken circles of death-smitten homes names for the roll of eternal fame.

The whole country was electrified by the news of the fearless assault of Rodgers and his Texans. Illustrated papers of the North carried pictures of the dramatic scenes.

In closing his report of the battle, General Van Dorn said: “I cannot refrain from mentioning here the conspicuous gallantry of a noble Texan whose deeds at Corinth are the constant theme of both friends and foes. As long as courage, manliness, fortitude, patriotism, and honor exist, the name of Rodgers will be revered and honored among men. He fell in the front of battle and died beneath the colors of his regiment in the very center of the enemy’s stronghold. He sleeps, and Glory is his sentinel.”

The deeds of this brave officer called forth not only the encomium of his commanding general, but also the approval and admiration of the big-hearted commander of the Union Army. By order of General Rosecrans, the body of the fallen hero was buried with military honors upon the field where he fell and the grave inclosed with wooden palings.

What sadder illustration of War’s ruthless waste of manhood could there be than is presented in the sacrificial death of that heroic son of Texas? What a wealth of courage, integrity, and high purpose that might have been utilized in the bloodless battles of a nation’s peaceful progress was forced to perish under the juggernaut of fraternal strife! What a scathing indictment of our civilization—our politics, our religion—is that lonely grave!

Among the officers killed were Colonel Rodgers, Second Texas; Colonel Johnston, Twentieth Arkansas; Major James, Twentieth Arkansas; Col. J. D. Martin, commanding the Fourth Brigade of Price’s Division.

5