Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 11 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 10: Silence in Carigara)

__________________________________________________________________________

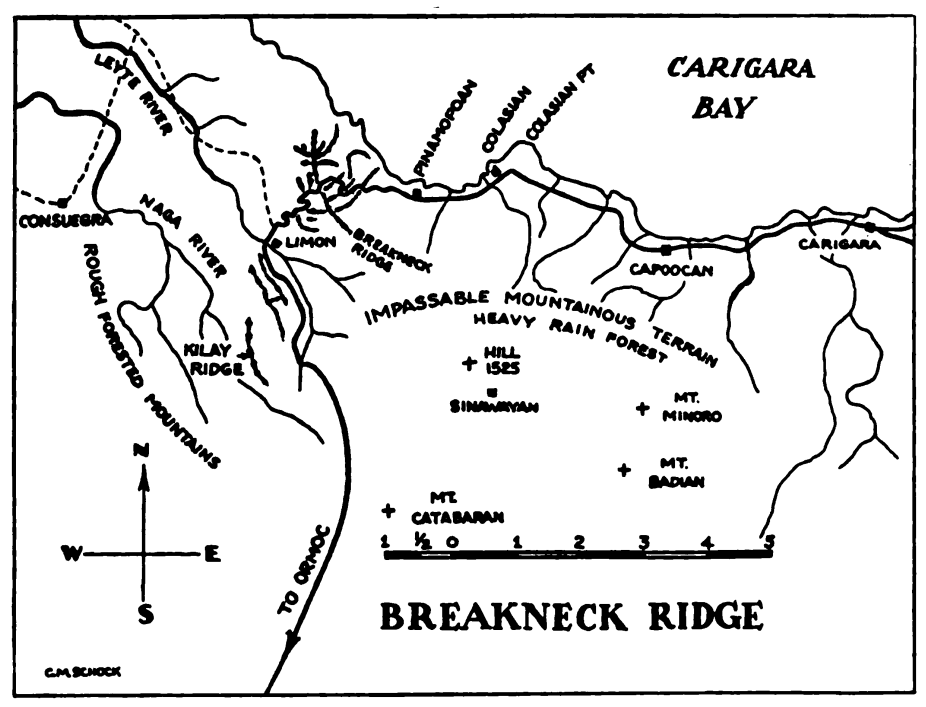

“The bitter battle of Breakneck Ridge had begun. It was to be fought over terrain ideally suited to defense, rough, rocky hills covered with kunai grass. The Ridge itself was not a single ridge, but a series of ridges, all of which were broken into knobs. There were innumerable ground pockets which were thickly wooded natural forts and whose defensive potentialities the Japanese had thoroughly exploited. There were elaborate systems of trenches. The entire area was packed with spider-holes. The road from Pinamopoan ran steadily upward, twisting through the hills. It crossed many streams and ravines. Complicating the entire operation was a condition of almost constant rain. There were no accurate maps of the area, and difficulty was experienced in keeping our attacks from breaking into a series of uncoordinated combats. A feeling grew among staff officers that the Ormoc Corridor would become another Guadalcanal.”

(from the Division Record)

___________________________________________________________________________

Over the muddy rim of his foxhole Sergeant Lewis peered at the dark line of bushes which skirted the base of the slope. The rain had stopped. A sullen dawn invaded the black heavens over Suicide Hill. It was a hill on a ridge, one of many, and toward the south were other ridges, and beyond them lay the towns of Limon and Ormoc. There was the distant boom of artillery coming in from the shore of Carigara Bay, and the rolling thunder of explosions as the shells hit the reaches of Breakneck Ridge. Nearby nothing moved. Yet — a trained ear could sense the jabber in the undergrowth two hundred yards away.

“Hey, Matt, wake up! Gil—!”

The sergeant’s foot prodded the sleepers in the soggy bottom of the emplacement.

“Who’s coming?”

“Dope!”

Stubby hands wiped mud from hair and eyes.

“Give ’em a bellyful.”

Abruptly they were awake. Crouched over their gun, skilled fingers checking the lay, the mechanism, the belt; eyes sunken from lack of sleep searching the downward slope in front; the gunner, and the gunner’s assistant. In one of the smaller holes an ammunition bearer yawned and swore softly.

“That you, Leo?” the sergeant said. “You guys had better keep awake.

“What’s up, Web?”

“Nothing.”

Nothing? Jap corpses littering the mushy slope were more eloquent than Web Lewis from Tennessee. In the twilight the bloated shapes of the dead sprawled like revelers frozen in weird immobility.

“So you woke us up,” said the gunner.

“Take it easy.”

“Wait and wait. Attack and attack and getting nowhere. Too goddam much waiting in this war. Too much shit.”

“You said it.”

“I’m sick of waiting.”

They waited. Beyond the welter of clouds the sun was rising. It was their fifth morning on Suicide Hill.

Five days and nights in slime-ridden holes. Breakneck Ridge! “Hold that hill,” the captain had said. “Don’t let the bums push you off.” Can’t move around at night if you don’t want your friends to shoot you. Piss in your hole, then sleep in it. Japs in front, Japs to both sides, Japs in the rear.

“Wonder if the Nips like war.”

“They like it no more than you do.”

“Then what’re the bastards fighting for?”

“Damned if I know.”

‘What are we fightin’ for?”

“So that some sons o’ bitches back home can get rich.”

“So that some Four F’s can screw our women.”

“You’re crazy… Hell, my goddam lighter ran out of gas!”

“Mine works… here… If the Japs want the f— Philippines, they can have them.”

Five days of agonized exertion on hillsides that tore your heart out. Five nights in mire with muscles aching to stretch in the open. Malaria now and rheumatism later. Jungle rot. Centipedes looking for a dry place in your pants. Lice nibbling crusted sweat. Cold hash and chocolate bars in your belly and naught else. Rain water gulped from rusty helmets to slake the strangling thirst. The evil whirr of mortar fragments, and sniper bullets slapping the muck a foot away. Dysentery.

The nearness of death and the awful distance of home.

A thought, never voiced: Jesus Christ, wonder if I’ll ever be walking down a lit-up street again.

“Raining again,” mumbled someone in tired disgust.

“So?”

“That rain’ll go on forever and the war as well.”

“And we, too,” growled the sergeant.

Rain splashed sloppily on the blood-stained grass. It hissed in the bushes and rattled on the helmets. It leaked into weapons and drenched the mud-caked fatigues. The whole sky seemed an assembly of gigantic sponges. Rain swamped the holes and squalched down the boots and ran in filthy rivulets across hollow cheeks and over the unshaven chins.

Rain and the Japs.

The Emperor’s men hated that machine gun on Suicide Hill. Each dawn they had attacked, and each afternoon. And each night they had moved stealthily up the wet slope, repeating their folly like robots in a continuous burlesque— tripping over wires which signaled their approach, hurling grenades and howling in the white-hot glare of counter-grenades, crumpling in the fire directed at the sounds of their advance.

It was light enough now to see the jagged backs of far mountains gray in the morning.

“Breakfast time!”

‘To hell with breakfast.”

Punctuating the mature dawn was a crackling of rifle fire. Single shots at first, followed by a fusillade, and then a tattoo of popping sounds came from the direction of the enemy line.

Mortars.

The men in the holes saw the projectiles come in from high-up. Mortar fire fell on Suicide Hill.

“Sit tight.”

Flash and sound and quick stabbing of fragments. The shells were falling short. It was as if the morning rocked with obscene laughter. The men crouched low, their helmets turned in the direction of the bursts. No one spoke, until there was a lull in the firing. The sodden tiredness had slipped from their minds. Sweat mingled with the rain on their faces.

The gunner smiled at his assistant. “Hey, Bill,” he said, “how about a nice cool glass of beer?”

“Make it a neat blonde, Matt,” replied Bill dreamily.

Matt edged his face toward the rim of the emplacement. He squinted down the slope.

“There they are,” he said loudly.

The border of bushes below them had come to life. There were the shapes of men running forward, dropping, springing up again and running. And there were bayonets on their rifles.

The sergeant was calm. “Fire,” he said.

They breathed hard. Sweat in their eyes half blinded them. The ammunition belt writhed in somber rhythm with the rapid succession of bursts. Right and left barked the Garands of the rifle men, and other guns chattered in support from an adjoining ridge.

Here and there a Jap stopped running, floundered and died. But others came on as if driven by some fantastic obsession, bounding through rain, hugging the ground, firing wild and yelling, leaping forward again into the blaze from the machine gun’s snout.

“Another belt — quick.”

“Here she goes.”

The attack failed, like the others. First there was hesitation, then milling confusion, then sprays of lead following the sprinting survivors to the shelter of the bushes.

“Cease fire.”

“Whew!”

The gunner stared at his hands. He looked sick and exhausted. Rain hitting the barrel of the gun went up in playful wisps of steam.

Again they waited.

The hours dragged. Four of them dozed in the slime. One watched, guessing at the hour’s end to wake his relief. Then noon time and half a can of hash and a chocolate bar for each man. Too weary to eat. No coffee. No cigarettes. Sniper fire in the rear kept the carriers from coming through. Coffee powder dissolved in a handful of rain, and more half-sleep populated by harassing shadows…

Transport planes hummed past above the clouds. Dropping supplies where neither truck nor carrying party could push through.

At mid-afternoon the enemy brought artillery to bear. The men on Suicide Hill watched the first shells burst a good hundred yards to their rear. The following rounds fell closer. Sixty yards. Creeping nearer. Thirty.

Against such eruption their gun became a futile toy. In their holes the men crouched low and the sergeant cursed. Cursing was no good. What was needed? Planes? Planes could see nothing but jungle. Counter battery fire? There was no telephone nor radio. Run for it? Stay and get it?

And who was then to defend this damned hill?

“Let’s get out of here.”

The sergeant timed the explosions. One more flash, vomiting mud.

“Now.”

He grasped his rifle and led in a swift dash to a clump of undergrowth a little way off. The others followed, one by one, pitching headlong on their faces as they cleared the impact area of the shells.

Silence.

“Anybody hurt?”

“No.”

“Clem — God damn you, answer. Are you all right?”

“I’m all right.”

“Disperse.”

They moved apart, searching for low spots among the vines and roots.

“And keep our gun covered,” the sergeant warned.

“All right.”

They hovered in the bushes and the downpour, their rifles and carbines inches above the engulfing slush, their eyes fixed on their silent gun and on the slope ahead.

The shelling ceased. The silence was so intense that to the watchers the beat of their hearts sounded like the pounding of buried machinery. Then there was a shot down the slope, and silence again.

A lone Japanese emerged from the bushes at the base of the hill. A will to self-destruction lay in his cocky gait. Would that gun up there fire?

The gun was still.

The lone enemy shouted a few strident words. He motioned his comrades to follow. The gun up yonder had been knocked out, no doubt.

Four enemies proceeded up the slope. They came at a running crouch and in single file. Their leader kicked the mud and laughed. On him the sergeant drew a careful bead.

“Matt,” he whispered, “you take the second in line. Leo — the third is your baby. Gil makes sure of the last. Bill, you watch. If one scrams, get him. Ready?”

“Let’s go.”

“Fire.”

There was a slight disturbance in the melancholy tangle of corpses on the hillside. One of the four flopped about for a while, like a fish cast ashore. A howl arose from the thicket below.

“Now they’ll wait till dark,” the sergeant said.

In the rain the machine gunners lay, not moving, while the dripping hours went by. Again one watched; the others dozed. Dusk lingered an hour, and then the night towered over the hills.

At that hour two groups of men crawled toward the abandoned machine gun on Suicide Hill. They crawled with infinite caution through the blackness and the wet grass. One was that of Sergeant Web; the other was a band of Japs. And each knew that the other was not far, sliding nearer in the silence of the night.

Clem, the ammunition bearer, was first to reach the gun. There it was, untouched, like a chained dog awaiting its master.

Matt detached the barrel and vanished in the night. Gil gathered up the tripod and followed. The others lugged away what grenades and ammunition there was left. They did not go far. The sergeant selected a low spot in the ground.

“Set it up,” he said.

No time to dig in. Their faces close to the ground they waited for the silhouettes of the enemy to appear over their abandoned emplacement. Minutes passed. A bullfrog croaked. A rocket flare ghosted into the rain. Now they could see the outlines of the Nip patrol, a cluster of shadowy blurs weaving low against the inky sky.

“Grenades,” the sergeant said softly. “Then fire at what’s left”

Breakneck Ridge— the Japs called it the “Yamashita Line.”

On peacetime maps the jumble of razorback ridges and cone-shaped heights had no name of their own. They just happened to be, a desperately overgrown barrier between Carigara Gulf and Ormoc Valley, shoved there by volcanic upheavals of long ago. Map makers had shied from thorough exploration: where there were five ridges, the maps showed one; mountains of dominating height were miles removed from spots assigned to them by the maps. As the campaign progressed, the whole tormented complex was named Breakneck Ridge. Individual ridges and heights were named by the men who fought for them, a privilege paid for at an exorbitant price.

The Japanese were trapped between Breakneck Ridge and Ormoc. They were determined to hold their “corridor” not only as a fortress, but as a base for counter assault. Americans were determined to break it. The outcome of this battle was to decide the outcome of the Philippines campaign.

The Division’s Twenty-First Infantry Regiment led the frontal assault on Breakneck Ridge. Opposing it in battle were elements of five Japanese divisions, veterans of Bataan, Manchuria and Singapore.[1]

But the battalions of the Twenty-First, on their way north to take over, were delayed by heavy rains. So, on the morning of November 3, the men of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment entered their fifteenth day of continuous battle. They left the area of Carigara at 7 A.M. in a column of battalions. Their goal was the coastal town of Pinamopoan, some seven miles to the west. Pinamopoan, at the foot of Breakneck Ridge, was the northern gateway into the Ormoc Valley.

The First Battalion, commanded by stalwart Colonel Thomas E. Clifford of Cereda, West Virginia, passed through the village of Capoocan without meeting resistance. Morale among the men, fatigued as they were, was high. They knew that relief was near, and the going that morning was good. To their right lay the beach, a crescent of black sand sketching to the headlands of Calusian Point; dark green slopes jutted skyward on their left. Between the ridges and the beach lay a belt of swampland through which the coastal road wound like a fragile ribbon.

A thousand yards west of Capoocan machine gun fire hit the vanguard. Although the road ahead seemed clear, the fire increased in intensity. The vanguard dispersed in the swamp and lay low. Scouts muscled forward to reconnoiter. They found a stream with almost perpendicular banks. There were the charred timbers of a bridge. The enemy was entrenched in the stream bed and under the bridge. He could not be reached by bullets, but he could rake the road and the adjoining swamp.

Guns of the Field Artillery pounded the area. But in the narrow defile of the stream bed the Japanese were vulnerable only to direct hits. A radio message told the artillery to cease firing. Clifford ordered the battalion mortars into action. The mortars thumped, but their shells failed to blast the Japs from their holes. A platoon of riflemen then climbed the ridge on the left to gain commanding ground. They found a Japanese ambush on a bluff overlooking the stream. “Able” Company was sent up the incline to reinforce the vanguard platoon.

The scouts groped through a fantastic tangle of thickets. The company lost its way on the hillside. It is not possible for a mass of men to move through jungle without making many noises. The underbrush crackled and there were the sounds of feet slipping on the treacherous slope. Without warning, the company came face to face with the Japs in ambush.

An immediate frontal attack was the only way out. Eleven Americans lost their lives in a wild and instant exchange of shots, and thirteen sagged wounded. The enemy counter-charged with bayonets, but was repulsed. Simultaneously, the remainder of the battalion assaulted the stream bed below.

Private Thomas Kennedy of Harrison, New Jersey, was the first man to cross the stream. Though every second soldier of his squad fell dead or wounded before he reached the bank, Kennedy jumped straight into a Jap hole, scrambled across the stream and up the far side. There he maintained a one-man bridgehead and pulled through.

From the slippery hillside “Able” Company’s men hurled grenades to clear the stream bed below them. The last grenade was expended. The Japanese replied with a hoarse “Banzai!” Staff Sergeant Louis Hansel of Mount Vernon, Kentucky, half plunged, half slid down the slope. He was going to get more grenades. He got them. He lugged grenades to his comrades on the ridge, and he lugged wounded with him when he returned for more. After a squad leader was wounded, Hansel remained and led the squad in the attack.

Soon every man in “Able” Company was committed to the close range fire fight, including messengers and cooks. The company commander, Captain Jack B. Matthews of Macon, Georgia, was unaware of twelve Japanese who suddenly charged his unit from the rear. Matthews wheeled when he heard them yell as they closed in. Two runners, a radio operator, and his orderly sprang to help their captain. They warded off the thrust. The Japs vanished. But a minute later they again broke out of the jungle like a pack of wolves. They lashed out with their bayonets and screeched their high-pitched screams. In the defense group some men staggered with bayonet wounds. An automatic rifleman who rushed to their aid was wounded. A sergeant named Max Keith, of Mars Hill, North Carolina, saw the fracas. He grabbed the wounded gunner’s grenades and B.A.R. All twelve of the attackers were slain.

Jack Matthews then led his men in a bayonet assault. It was 6 p.m. before the last Jap defending the stream position was killed.

As resistance developed at the stream crossing west of Capoocan, another force was ordered to make an amphibious flanking attack on Pinamopoan. Their mission was to cut off the Japanese forces on the coastal road. “King” Company of the Thirty-Fourth embarked on seven amphibious tractors. They skirted the coast. Artillery bursts on the beach of Pinamopoan showed them where they should land. The “Alligators” sprayed the shore with machine guns as they came in. The riflemen then pushed ashore and up steep, grassy slopes defended by double their number of Japs.

The enemy fired from anti-tank guns, field cannon and heavy machine guns. The range was 250 yards. “King” Company replied with machine guns, rifles and mortars. The position quickly became untenable. An artillery observation plane cruising over head reported a truck convoy of Japanese moving toward the beach. Later that afternoon the Cub plane was shot down by strafing Zeroes. A retreat was ordered. “King” Company fell back to the beach. Men carried their wounded. The “Alligators” nosed inshore to carry the task force to sea. The Japanese promptly counter attacked.

Two artillery observers who had accompanied the expedition saved the retreat from becoming a rout. Robert Campbell of Pipestone, Minnesota, and John W. Strasser of Maquoketa, Iowa, directed the fire of batteries emplaced five miles to the east. The howitzer shells screamed in to cover the retreat. Their bursts scattered the enemy onset. The grassy slopes caught fire. The beach shuddered under the might of the explosions. Fragments fell among “King” Company’s platoons. Unflinchingly the two observers drew the barrage of their 155 millimeter batteries to within 150 yards of their own positions. Dazed and numbed, they were the last to leave the beach.

All night the Division’s field artillery battalions massed their fire on Pinamopoan. On the morning of November 4, infantry slogged down the coastal road and seized the town. Two hundred Japanese dead were found in Pinamopoan. Six artillery pieces were captured. That night the spearhead of the Thirty-Fourth dug in on the foothills of Breakneck Ridge. Fresh battalions of the Twenty-First Regiment relieved them at dawn of November 5. The change of forces took place under a torrential rain. In the dim gray light the newcomers eyed the country ahead of them. Winding upward into inscrutable mountains lay the Ormoc Valley trail.

Colonel William J. Verbeck of Brooklyn and West Point, commander of the Twenty-First, led a patrol which reconnoitered the sinuous approaches to Breakneck Ridge. Upon his return he ordered the attack to proceed. Artillery observers accompanied by riflemen sliced to a height named Observation Hill. Another force advanced toward a ridge with twin peaks which later were dubbed Hot Spot Knob and Suicide Hill. Before the day ended the assault groups were split, isolated and surrounded. Snipers waylaid details carrying food and ammunition from the coast.

A scout pushing through kunai grass and blinding rain halted and turned. To the soldier behind him he said, “This f— rain! I can’t see a f— thing.”

“Let me go ahead for a while,” the other said.

“Keep your eyes open,” warned the scout.

“Okay.”

Private Charles Feeback of Carlisle, Kentucky, took over the lead of the advance. Jammed under his right arm was a submachine gun. He used its muzzle to shove aside the head-high grass. All of a sudden he stood stock still. In a foxhole four feet away, his rifle cocked, lurked a Jap. Feeback’s finger froze on the trigger of his gun. The forty slugs cut the Jap almost in two. Feeback raised his arm overhead, then pointed forward.

“All clear.”

Not for long. A little further up the hillside the Kentuckyman heard a metallic tap in the grass to his right. A Jap was cocking a grenade. The grenade, tossed high, plopped down at his feet.

The volunteer scout dived sideways into the grass. The grenade roared. Feeback did not move. He waited. He waited until he saw a slant-eyed head rise cautiously in the grass. In that instant the Kentuckyman drilled it between the eyes.

That was the beginning of the bitterest fighting of the campaign. From their maze of holes and tunnels on and between the hills the Japanese had cut narrow, interlocking fire lanes through jungle and kunai. Machine guns spat along these lanes. Snipers fired from secret perches. Enemy mortar crews dug into the world’s best hiding place covered ravines and hollows with a deadly pattern of bursts. Jap artillery grumbled from more distant ridges. The Division’s assault teams seized the initial ridges and knolls. The Japanese launched counter attacks. Four Banzai charges hit the perimeters between the afternoon of November 5 and dawn of November 6. Platoons were isolated and companies were broken up. Infiltration was constant and impossible to check. Some of the Division’s units fell back. Others, cut off, held out through days of rain and foxhole death. Often it became impossible to bring out the wounded; many died in muck and rain. Companies which entered the struggle one hundred and sixty strong emerged with sixty men still on their feet before they had broken the back of the “Yamashita Line.”

Japanese “Special Attacking Units” raged around the summit of Observation Hill. “King” Company was sent to reinforce the men on top. During one of their Banzai rushes the Nipponese came within grenade range of a machine gun platoon. Captain Neil Reid of Chicago, Illinois, recognized the danger. Under direct fire he moved the machine gun squads to new positions. The onslaught was repelled. The Japs streamed downhill, leaving sixty-five corpses to rot in the rain.

When ammunition ran low, volunteers from “Mike” Company set out to truck it up the road from Pinamopoan. They loaded their truck with mortar shells and machine gun ammunition and drove uphill through unspeakable mud. They met sniper bullets on the outskirts of Pinamopoan. They met machine gun bursts as their truck climbed the pass into Breakneck Ridge. Then mortar shells began to fall around them. The truck did not stop. Its engine rattled and fumed, and its double wheels churned the mire. Atop the ammunition, “Mike” Company’s men lay flat. Then a mortar shell exploded hard in front. The truck stopped.

Sergeant Paul Corfield of Cato, New York, jumped from be hind the shattered windshield. He wanted to check on the damage. He knelt between the front wheels and suddenly an expression of astonishment invaded his face. He sank into the mud. He moved an instant and lay still.

“Jesus Christ, they killed Paul,” said Sergeant Jacob Meyer, whose home was in New Orleans.

Meyer, too, had jumped from the truck. He spotted the Jap who had killed Corfield. From the roadside he fired. Somewhere in the jungle a machine gun chattered. Sergeant Meyer fell, mortally wounded. By now Japs swarmed from the underbrush on both sides of the Ormoc Trail.

Sergeant Antonio Pepe of Brooklyn, New York, yelled to his two remaining comrades: “The bastards want the ammunition. Defend that truck!”

He and Private Melvin Taylor of Alton, Illinois, lay under the truck and defended it. Behind the truck crouched Private Lester Francis of Birdsboro, Pennsylvania. The Japs swarmed closer. Pepe and Taylor fired. Francis fired. Some Japs fell, but the others came on, screaming. Bullets twanged among the tires. Grenades burst in fans of fire and mud. Taylor heard an outcry and a moan. Lester Francis was dead. Antonio Pepe was dead.

Now the boy from Illinois defended the ammunition truck alone. He defended it until a patrol, investigating the firing, drove the marauders back into the jungle.

On the neighboring hilltop an enemy thrust had cut a rifle platoon in two. The dripping sword grass blades vibrated with the din of fighting, but not much could be seen. The space between the two separated groups was occupied by Japanese. In the same space, too, American wounded lay shouting for help. Corpsman George A. Gregoric of McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, prowled through the wedge. Thrice he came face to face with snipers and dodged into the kunai. He found the wounded and gave them first aid. He stayed with them until relief arrived.

The Japanese attempting to storm Observation Hill during the night were terror-stricken when their third wild charge at 5 A.M. was answered with an equally savage counter charge. Grenades and bayonets clashed at close quarters. The Japs “Banzais” became cries of dismay; the Americans emitted howls and Yankee abuse. The man who coolly organized and led this counter thrust was Captain Tom Suber of Whitmire, South Carolina, “King” Company’s commander.

Private Charles Clemmer, of Philadelphia, saw a Jap jump out of the night and shoot a squad leader through the head. Clemmer fired a burst from his automatic rifle — and missed. The Jap tossed a grenade. The grenade struck the ground between Clemmer and his assistant gunner. Clemmer grasped the grenade and tossed it back. It blasted the Jap’s head off his shoulders.

A mortar observer named Leon Taylor, from Fort Worth, Texas, lay under hostile artillery fire, directing the firing of his own mortars on Japanese concentrations on the hillside. When the riflemen were ordered to fall back, mortarman Taylor remained and became a sniper. He circled the hilltop, darting from niche to niche. He beat the enemy at his own game. By his marksmanship four Japanese died.

Private Edward Griggs of Cornersville, Tennessee, drove a jeep three times along the fire-swept Ormoc Trail to bring five wounded soldiers to safety. Private Orville Schubert of Alice, North Dakota, covered the withdrawal despite a barrage of grenades. During a Japanese bayonet attack at 2 A.M., Technician Carmin Santangelo of the Bronx, New York, lugged four wounded men through skirmish, mud and rain. Helping him was Private Robert Miller of Saint Peter, Minnesota. Rejoining the fight, Miller carried ammunition. At dawn he spotted a trail running through a gully. He saw an enemy patrol move up the trail and stopped it with eight shots from his Garand. At his side, bent over a bleeding man, was Corpsman Willard Jenner of Sherwood, North Dakota. Jenner had tended the wounded all through that ugly night. Miller pointed at the fresh blood on the aid man’s uniform : “Hey Will, you’re wounded yourself,” he said.

Replied Will Jenner: “I know, I know.”

Commanding a platoon of heavy machine guns was Sergeant Andrew Pristas of Conneautville, Pennsylvania. In the face of enemy attacks from three sides and sniper fire from the rear, Pristas passed from machine gun to machine gun, checking on ammunition and targets. His steady words of confidence did much to keep the specter of battle-exhaustion at bay. When Japs came too close, Pristas tossed grenades. When a gunner ran out of ammunition, Pristas was at his side with another belt to help him reload quickly. When his force finally abandoned the ridge, Pristas and his gunners remained behind to prevent the Japs from breaking into the retreat. Only when friendly artillery shells began to explode in the abandoned perimeter did Pristas and his crew take to their heels.

Entrenched near a bend of the Ormoc Trail, Private Truman Simmons of Caves City, Arkansas, saw a jeep ambushed by snipers. He saw the driver slump over the wheel. Another man who was bleeding from the neck struggled to get out of the car. The Japanese now fired tracer bullets to set the gasoline in the jeep’s tank afire. Simmons leaped out of his hole and raced to ward the jeep. He saw that both occupants were badly wounded. He freed them from the vehicle and helped them into a clump of grass. He bandaged their wounds to stop the flow of blood and he gave them sulfa tablets and water. After that the Arkansan returned to his foxhole to fight it out with the snipers. The jeep was later commandeered by Private Glenn Brodine of Sandpoint, Idaho, who used it to taxi wounded comrades to Pinamopoan.

Leal Marlett of Newberry, Michigan, worked in no-man’s-land to treat the wounded and to mark their location for the litter squads. Then came the news that the corpsmen of an adjoining platoon had been wounded, and that the platoon needed medical help. Marlett took over the wounded aid man’s job on top of his own. Like many another medic on Breakneck Ridge, Leal Marlett was killed in action.

In the pitch-blackness of the night rains a machine gun squad of four fought until all were wounded except its leader, Private Laverne E. Baker of Freeport, Illinois. Two of the men had been hit by fragments from grenades. The third had gone down under a bayonet stab in the dark. Baker manned the gun alone. He repulsed a Japanese onset. The surviving Japs hugged the ground some thirty yards away and waited. Somehow Baker managed to drag his three wounded team-mates to the rear. He himself went forward again. He salvaged his gun and mounted it in an alternate position unknown to the Japs.

Every minute of the night of November 5 to November 6 was loud with the sounds of gunfire and of men taking each other’s lives. Staff Sergeant Jose Gomez of Carlsbad, New Mexico, was wounded in the leg when a Jap assault group broke into his squad’s position. Gomez was carried to the aid station near the center of the hilltop. While the medics patched his leg, other wounded were brought in. “What’s up?” asked Gomez.

“They’re attacking again,” one of the other wounded men said.

Jose Gomez escaped the medics. He hobbled back to his decimated squad and fought until the second attack was shattered. For the second time he was then carried to the aid station. This time he did not come back.

The scout of a platoon climbing a ridge to reinforce a surrounded party of artillery observers received machine gun fire from the flank. A cunningly masked pillbox was firing down a narrow trail. The scout signaled his platoon to halt. Then, single-handedly, he engaged the strongpoint while the platoon maneuvered. The nest was destroyed with flame-thrower and grenades. The scout was Private Anthony Jasiukiewicz, American, from West Warren, Massachusetts.

Nearby another squad lay in battle. At this point the enemy tried infiltration. It was the second attack and already half of the squad was out of action. The Japanese crept on their bellies through sword grass seven feet high. Around their necks they bore canvas sacks filled with grenades. Ahead of them they pushed rifles, with bayonets fixed. The purpose of night infiltration is to cross the perimeter unobserved, then attack it from within.

Through the rushing sound of rain Sergeant Dominic Castro, of Los Angeles, heard a faint rustling. The soldier nearest him lay glassy-eyed, a victim of battle fatigue. Castro let out a piercing yell. That roused the remainder of his squad. At the same time he fired. A few feet away in the darkness Japs sprang up and threw grenades. Then they flopped to the ground to evade the fragments. An instant after the bursts they sprang forward and charged. They howled as they had been taught to howl in training camps in China and Japan. The purpose of their howling was supposed to paralyze their antagonists with fright; actually it signaled their location. On they came, their bayonets at groin-level.

The men of Castro’s squad fired for their lives. Then they, too, sprang up to meet the collision. Castro was hit by a grenade. A moment later he felt a Jap bayonet go through him. He shot the bayonet wielder in the face. The force of the muzzle blast bared the Jap’s skull bones. After the last round had left his magazine, Castro reversed his rifle and fought with the butt. His staying power made his squad stand fast.

A B.A.R. man named Francisco Mosteiro of Fall River, Massachusetts, had an ugly head wound caused by a grenade. But his automatic rifle clattered until the charge was repulsed; then Francisco collapsed. Another automatic rifleman spotted the muzzle flashes of a Jap machine gun which caused havoc along the perimeter; in the dripping darkness he rose to a standing position and engaged the Japanese gunners in a duel across ten yards of grass aglow from the passage of bullets.

The long night drew to an end. At 5 A.M. the enemy made his last frantic charge. It followed a barrage of machine gun, knee-mortar and artillery fire. The Japanese were within three yards of the line of foxholes and threw scores of grenades. Into one rifleman’s hole plopped four grenades. He recovered three and hurled them back in a second. The fourth slipped from his hand and rolled back into the hole. The soldier crushed it into the mud with his right foot. That saved his life, but it blew off his foot. The Japs broke into the perimeter where “Mike” Company’s machine gunners had their emplacements. In the gunners’ ears the brutal rataplan of their guns was sweet music in the face of the Banzai men’s screams. “Those little men with the long bayonets,” one of the gunners said at dawn, “that’s not so bad. But their howling is something that grabs your guts and twists them.” There were many cries for aid men. Wounded men were wounded again, and some of the wounded were killed. The machine gunners fell back. “King” Company counter attacked with bayonets and retook the emplacements. Dead Japs were rolled out of each recaptured hole.

Where the bayonet fails and the rifle butt misses, there is still the trench knife, the kick to the testicles, the strangling, and the gouging of the eyes. In one attack every man in a platoon commanded by Lieutenant Walter Easton of Yreka, California, was killed or wounded. Easton hurriedly moved through blackness and pouring rain and brought replacements to the line — cooks, bakers, messengers and truck drivers.

Dawn came, heavy and gray. The night rains faded into a steady drizzle. Men lay in the mud by the side of their foxholes. The foxholes were full of muddy water. The muddy water was stained with blood. Here and there a lifeless head, a hand, a knee protruded from the water-filled holes. Corpses along the edge of the perimeter resembled a congress of reptiles gazing motionless through mud-caked grass. There was no pause in the horror. All through the somber morning the Japanese pursued their counter offensive. The Division’s assault teams were thrown back to the beach. At one point Lieutenant Easton, with fifteen volunteers, covered the retreat. And even after this covering force had retreated, a few remained.

Private First Class Ernest Shannon of Lamar, Kansas, went back to rescue a friend whose arm and shoulder had been mangled by machine gun fire. Sergeant John Mashek of Wyndmere, North Dakota, remained to destroy abandoned weapons to prevent their falling into enemy hands.

Of the situation on November 6, 1944, the Division Record reports:

“Casualties were high. Enemy pressure had been brought heavily against our companies, and these units were pushed off their high ground positions during the morning. By 1300 they had withdrawn to the beach. “C” Company, reinforced by Filipino guides, had been sent to occupy Hill 1525, a dominating terrain feature far to the left flank, but this unit returned just before dark to report that the guides had lost their way.

“At the close of the day the Japanese had occupied Breakneck Ridge and the approaches leading to it from the north.”

(Continue to Chapter 12: Children of Yesterday)

___________________________________

[1] The Japanese divisions engaged in the battle for the Ormoc Corridor were the First Division, the Sixteenth, the Twenty-Sixth, the Thirtieth, and the One Hundred and Second. They were joined by other Japanese units in the later stage of fighting.