Editor’s note: The following is extracted from History of English Literature from Beowulf to Swinburne, by Andrew Lang (published 1921). All spelling in the original.

Of all these Latin chroniclers by far the most important was Geoffrey of Monmouth, Bishop of St. Asaph, who finished his “History of the Britons” about 1147. Geoffrey, as has been said, is not a real historian, but something much more interesting. He introduced to the world the story of King Arthur, which at once became the source and centre of hundreds of French romances, in verse or prose, and of poetry down to Tennyson and William Morris. To Geoffrey, or to later English chroniclers who had read Geoffrey, Shakespeare owed the stories of his plays, “Cymbeline” and “King Lear”. Though Geoffrey did not write in English but in Latin, he is one of the chief influences in the literature, not only of England, but of Europe, mediaeval and modern.

All readers of the “Morte d’Arthur” of Sir Thomas Malory (about 1470), and the “Idylls of the King,” and William Morris’s short poems about Arthur and Guinevere, are naturally curious to know if ever there were a real fighting Arthur, and to trace the sources of the countless French and English romances about him and his Court. Where did Geoffrey of Monmouth get his information about this island, from the days of the fabulous Roman who settled it (Brut, or Brutus), to King Arthur’s time? We must look at what is known or reported about Arthur.

Bede, the historian, writing about 700-730, says nothing about Arthur, but he does speak briefly about the period (500-516) in which Arthur, if there were such a prince, must have existed. Bede takes from the Welsh writer in Latin, Gildas (about 550) the fact that, up to the date of the siege of Badon Hill (516), forty-four years after the Anglo-Saxons came into Britain, “the British (Welsh) had considerable successes under Ambrosius Aurelianus,” perhaps the last of the Romans. “But more of this later,” says Bede, who never returns to the subject. He may have expected to get more information, and that information might have included some account of Arthur, of whom Gildas makes no mention. Bede says nothing of the fable of Brut, which may not have been invented in his time, or, if known to him, was regarded by him as fabulous. Next we have a book attributed to the Welsh Nennius, a “History of the Britons,” which is really a patchwork of several older records, and there is the “Annales Cambriæ,” annals of Wales. Nennius (about 800?) makes Arthur (“the war-leader” not the king) win twelve great battles, ending with Badon Hill.

The names of the battles are given, the first is on the river Glein. Now one Glein is in Northumberland, the other in Ayrshire. Four battles are “on the Douglas water in the country called Linnuis”; if “Linnuis” is the Lennox, there are two Douglas waters there, which fall into Loch Lomond, between them is Ben Arthur. The sixth battle was “by the river Bassas,” a “Bass” being a hill shaped like an artificial mound, for example the isle called “the Bass” in the Firth of Forth. There are two Basses on the river Carron, in Stirlingshire, and here may have been the sixth battle. The seventh was “Cat Coit Celidon,” “the battle (cat) of the wood of Celyddon,” that is Ettrick Forest, perhaps the fight was on the upper Tweed. The eighth battle is thought to have been waged at Wedale, in the strath of Gala water, a tributary of Tweed, which it reaches at Galashiels; the ninth at Dumbarton, which means “the castle of the Britons”; the tenth near Stirling, where a very late writer says that Arthur kept the Round Table; the eleventh at “Agned Hill”; that is Mynyd Agned—Edinburgh Castle rock; and the twelfth was “the siege of Badon Hill,” perhaps a hill on the Avon, near Linlithgow, which has remains of strong fortifications, and is called “the Buden Hill,” or “Bouden Hill”. (It is not easy, however, to see how the a in Badon became the u in Buden.) Finally the great battle of Camlon, where Arthur fell, is taken to be at a place long called Camelon on the Carron, in Stirlingshire, where Arthur met Saxons, Picts, and Scots, under Medraut, (Modred), son of Llew, or Lothus, to whom Arthur had granted Lothian. On the other side of the river was an ancient building called, as far back as 1293, “Arthur’s Oven”; it was destroyed by a laird at the end of the eighteenth century.

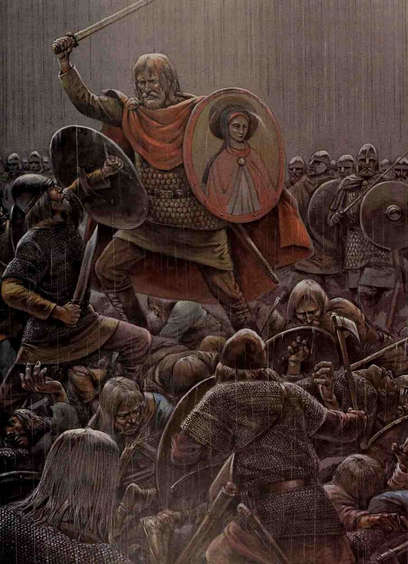

If all these conclusions, drawn by Mr. Skene from legends, Nennius, and place-names, be correct, Arthur was a real war-leader, fighting for the Britons, that is the Welsh of Strathclyde, whose country stretched from Dumbarton down through Cumberland. Even Geoffrey of Monmouth makes Arthur fight between Loch Lomond and Edinburgh, and give Lothian to King Lot, that is Llew, whose son, Medraut (Modred), turns traitor to Arthur. Bede places the battles at a time when the Picts had made an alliance with the Saxons, and these two peoples were in contact with each other not down in Cornwall, where later writers place “the last battle in the west,” but exactly where Arthur seems to have fought, in the fighting place of Edward I and the Scots—from Carlisle to Dumbarton and Falkirk, and in Ettrick Forest and round Edinburgh, a region where several hills bear Arthur’s name.

We need not, then, give up Arthur as a fabulous being, though legends far older than himself came to be told about him. In the oldest Welsh poems that survive he is mentioned among scores of other old heroes, now forgotten, and is always named as a great war-leader, “Emperor and conductor of the toil”.

One mention is important. In a long Welsh poem on the graves of many heroes now forgotten, we read:—

The grave of March, the grave of Gwythar,

The grave of Gwgwan Gleddyvrudd,

A mystery to the world, the grave of Arthur.

(Or “not wise to ask where is the grave of Arthur.”)

Thus it appears that, even in very early Welsh poetry, the Grave of Arthur (like that of James IV, slain at Flodden), was unknown; hence he was believed, like King James, not to be dead; he was in “the island valley of Avilion,” and would come again to help his people, when he was healed of his grievous wound.

Several of his companions in the later French and English romances, such as Geraint, Kay, and Bedivere, were also known to these very early Welsh poets. Moreover, there exist in the Welsh “Mabinogion” (“Tales for the Young”), very ancient stories of Arthur which do not resemble the ordinary later romances about him, but are infinitely older and more poetical: such are “Kulhwch and Olwen” and “The Dream of Rhonabwy”.

Probably about 1066 there were many tales of Arthur surviving in Brittany, a Brython (Welsh) country from which the exiled prince of South Wales returned home in 1077. If he brought these tales back and if the Welsh poets took them up, there would be plenty of Welsh Arthurian literature between 1077 and 1140, or thereabouts, when Geoffrey of Monmouth produced his “History of the Britons”. He says that he has had the advantage of using a book in the Breton tongue, which Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford, brought out of Brittany; this book he translates into Latin.

No such book can be found. It is probable that Geoffrey used Welsh and Breton traditions, and the patchwork book, parts of it very early, called the “History of the Britons,” attributed to Nennius (about 796). In this we have a mixture of the real fighting Arthur of about 520, and the fabulous Arthur, a wonderful, powerful being, like all the old heroes of fable, who goes down to the mysterious land of darkness, like Odysseus and the Finnish Waïnamoïnen.

The patchwork book of Nennius derives the name of Britain from that person of pure fantasy, “Brut,” “Brutus,” great-grandson of Æneas; who sailed to the Isle of Albion. Now “Brut” was invented merely to explain the name “Britain,” and to connect the Britons, or Welsh, with the Trojans. In the same way the Scots had framed false histories of their ancestress Scota, who came from Scythia to Ireland, by way of Egypt, Athens, and Spain.

All these legendary and fictitious materials, and others, were used by Geoffrey in what he called a “History”; and his “History,” in spite of criticism, became the most popular book of the age. He begins with the flight of Æneas from Troy, and the flight of the great-grandson of Æneas, Brutus, to the Isle of Albion, “inhabited by none but a few giants”. Brut builds New Troy (London) on the Thames, and so the romance runs on, a mere novel of adventures, those of Shakespeare’s “King Lear” and “Cymbeline,” for example, mixed up with history from Bede, till we come to Merlin the Enchanter, and Uther Pendragon, and the mysterious birth of Arthur, who is crowned king, and slays 900 Saxons with his own sword in one battle, conquers all Northern Europe and France, and defeats the Romans, all of which is sheer mediaeval fable. At home, in a great fight (“the battle of Camlan” it is called in older books than Geoffrey’s) he kills Modred, and is carried to the Isle of Avallon or Avilion, to be healed of his wounds.

Geoffrey ends by requesting historians, his contemporaries, such as William of Malmesbury, “to be silent concerning the “History of the Britons,” since they have not that book written in the British tongue, which Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford, brought out of Brittany”. This is mere open banter. Geoffrey was not likely to show them that book!

Even in the old Welsh tale of the great boar-hunt, a story far earlier than Geoffrey’s time, Arthur is surrounded by many fabulous heroes, really characters of fairy-tale, like them who followed Jason in the search for the Fleece of Gold. All of them can do miraculous feats, like the heroes of “the dream-time,” “the dark backward” of unknown ages. These companions of Arthur become, at least some of them do, the Knights of the Round Table in the later romances, but we do not yet hear of Launcelot, or of the Holy Grail.

From Geoffrey’s book come the French poetical and adorned version of Wace (1155), many French romances, and finally a vast throng of chivalrous and romantic fancies cluster round the great name of Arthur. Geoffrey’s was a book that gave delight to every one, ladies as well as men, for in the marriage of the traitor Modred with Guinevere the wife of Arthur, and in Arthur’s revenge, was the germ of a world of romances. The conquest, too, by Arthur, of Gaul and Aquitaine, inspired, and, to their minds, gave an historical excuse for the ambition of English kings to recover these old dominions of Britain. Caxton, our first printer, long afterwards wrote that not to believe in Arthur was almost atheism.

Geoffrey also translated into Latin out of Welsh the prophecies attributed to the enchanter Merlin. If they had any meaning in Welsh, in Latin they have none. Hotspur, in Shakespeare’s “Henry IV,” is weary of Owen Glendower’s talk

Of the dreamer Merlin and his prophecies,

And of a dragon and a finless fish,

A clip-wing’d griffin and a moulten raven,

A couching lion, and a ramping cat,

And such a deal of skimble-skamble stuff.

Nevertheless, three centuries after Geoffrey wrote, men who thought themselves wise and learned believed that not only Merlin but Bede were true prophets, who foretold the victories of Joan of Arc (1429).

It must be kept in mind that Geoffrey says nothing about these great characters in later Arthurian romances, Launcelot, Galahad, Tristram and Iseult, and nothing about the mysterious Holy Grail, and the Quest of the Grail. How and whence these parts of the Arthurian legend arose, how much of them comes from ancient Celtic legend, how much from the invention of French romancers, is still a mystery. Geoffrey, however, made Arthur, Merlin, Guinevere, and Modred familiar to all his readers. All Englishmen were proud of Arthur of Britain, though, of course, in his life he was the deadly foe of the English.

Nennius is a fascinating study and by far my favorite Medieval historian, if only because his sources are so wildly disjointed and challenging. I had briefly considered doing my thesis on his Historia Brittanum, trying to locate and explain as many of his sources as I could. But it became apparent very quickly that such a work would be the labor of a lifetime, not a 6-hour HIST-899 grad course…

5

[…] (Men of the West): Of all these Latin chroniclers by far the most important was Geoffrey of Monmouth, Bishop of St. […]