Editor’s Note: The following is extracted from The Naval History of the United States, Volume 1, by Willis J. Abbot (published 1890). In the words of the author, “This combat is the earliest action upon American waters of which we have any trustworthy records. The only naval event antedating this was the expedition from Virginia, under Capt. Samuel Argal, against the little French settlement of San Sauveur.”

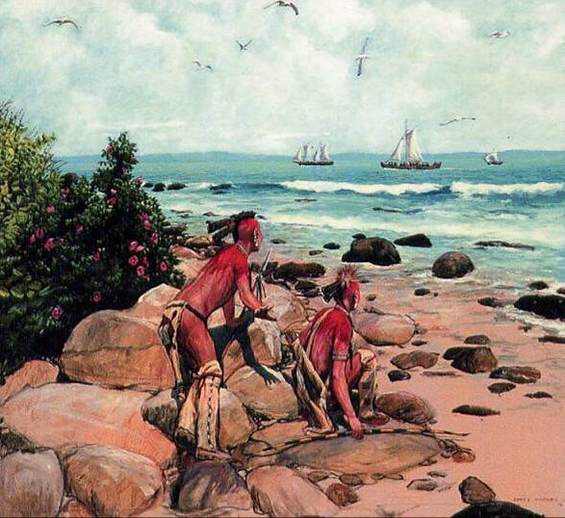

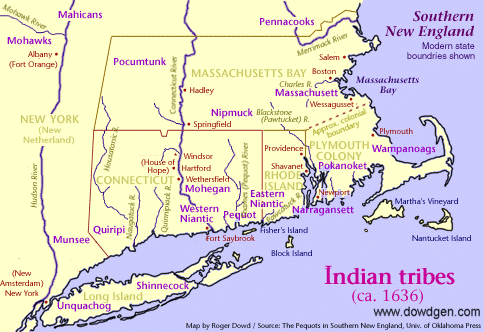

In May, 1636, a staunch little sloop of some twenty tons was standing along Long Island Sound on a trading expedition. At her helm stood John Gallop, a sturdy colonist, and a skillful seaman, who earned his bread by trading with the Indians that at that time thronged the shores of the Sound, and eagerly seized any opportunity to traffic with the white men from the colonies of Plymouth or New Amsterdam. The colonists sent out beads, knives, bright clothes, and sometimes, unfortunately, rum and other strong drinks. The Indians in exchange offered skins and peltries of all kinds; and, as their simple natures had not been schooled to nice calculations of values, the traffic was one of great profit to the more shrewd whites. But the trade was not without its perils. Though the Indians were simple, and little likely to drive hard bargains, yet they were savages, and little accustomed to nice distinctions between their own property and that of others. Their desires once aroused for some gaudy bit of cloth or shining glass, they were ready enough to steal it, often making their booty secure by the murder of the luckless trader.

It so happened, that, just before John Gallop set out with his sloop on the spring trading cruise, the people of the colony were excitedly discussing the probable fate of one Oldham, who some weeks before had set out on a like errand, in a pinnace, with a crew of two white boys and two Indians, and had never returned. So when, on this May morning, Gallop, being forced to hug the shore by stormy weather, saw a small vessel lying at anchor in a cove, he immediately ran down nearer, to investigate. The crew of the sloop numbered two men and two boys, beside the skipper, Gallop. Some heavy duck-guns on board were no mean ordnance; and the New Englander determined to probe the mystery of Oldham’s disappearance, though it might require some fighting. As the sloop bore down upon the anchored pinnace, Gallop found no lack of signs to arouse his suspicion. The rigging of the strange craft was loose, and seemed to have been cut. No lookout was visible, and she seemed to have been deserted; but a nearer view showed, lying on the deck of the pinnace, fourteen stalwart Indians, one of whom, catching sight of the approaching sloop, cut the anchor cable, and called to his companions to awake.

This action on the part of the Indians left Gallop no doubt as to their character. Evidently they had captured the pinnace, and had either murdered Oldham, or even then had him a prisoner in their midst. The daring sailor wasted no time in debate as to the proper course to pursue, but clapping all sail on his craft, soon brought her alongside the pinnace. As the sloop came up, the Indians opened the fight with fire-arms and spears; but Gallop’s crew responded with their duck-guns with such vigor that the Indians deserted the decks, and fled below for shelter. Gallop was then in a quandary. The odds against him were too great for him to dare to board, and the pinnace was rapidly drifting ashore. After some deliberation he put up his helm, and beat to windward of the pinnace; then, coming about, came scudding down upon her before the wind. The two vessels met with a tremendous shock. The bow of the sloop struck the pinnace fairly amidships, forcing her over on her beam-ends, until the water poured into the open hatchway. The affrighted Indians, unused to warfare on the water, rushed upon deck. Six leaped into the sea, and were drowned; the rest retreated again into the cabin. Gallop then prepared to repeat his ramming manœuvre. This time, to make the blow more effective, he lashed his anchor to the bow, so that the sharp flukes protruded; thus extemporizing an iron-clad ram more than two hundred years before naval men thought of using one. Thus provided, the second blow of the sloop was more terrible than the first. The sharp fluke of the anchor crashed through the side of the pinnace, and the two vessels hung tightly together. Gallop then began to double-load his duck-guns, and fire through the sides of the pinnace; but, finding that the enemy was not to be dislodged in this way, he broke his vessel loose, and again made for the windward, preparatory to a third blow. As the sloop drew off, four or five more Indians rushed from the cabin of the pinnace, and leaped overboard but shared the fate of their predecessors, being far from land. Gallop then came about, and for the third time bore down upon his adversary. As he drew near, an Indian appeared on the deck of the pinnace, and with humble gestures offered to submit. Gallop ran alongside, and taking the man on board, bound him hand and foot, and placed him in the hold. A second redskin then begged for quarter; but Gallop, fearing to allow the two wily savages to be together, cast the second into the sea, where he was drowned. Gallop then boarded the pinnace. Two Indians were left, who retreated into a small compartment of the hold, and were left unmolested. In the cabin was found the mangled body of Mr. Oldham. A tomahawk had been sunk deep into his skull, and his body was covered with wounds. The floor of the cabin was littered with portions of the cargo, which the murderous savages had plundered. Taking all that remained of value upon his own craft, Gallop cut loose the pinnace; and she drifted away, to go to pieces on a reef in Narragansett Bay.

[…] Source link […]

3.5