Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail, by Theodore Roosevelt (published 1888).

The old race of Rocky Mountain hunters and trappers, of reckless, dauntless Indian fighters, is now fast dying out. Yet here and there these restless wanderers of the untrodden wilderness still linger, in wooded fastnesses so inaccessible that the miners have not yet explored them, in mountain valleys so far off that no ranchman has yet driven his herds thither. To this day many of them wear the fringed tunic or hunting-shirt, made of buck skin or homespun, and belted in at the waist,—the most picturesque and distinctively national dress ever worn in America. It was the dress in which Daniel Boone was clad when he first passed through the trackless forests of the Alleghenies and penetrated into the heart of Kentucky, to enjoy such hunting as no man of his race had ever had before; it was the dress worn by grim old Davy Crockett when he fell at the Alamo. The wild soldiery of the backwoods wore it when they marched to victory over Ferguson and Pakenham, at King’s Mountain and New Orleans; when they conquered the French towns of the Illinois; and when they won at the cost of Red Eagle’s warriors the bloody triumph of the Horseshoe Bend.

These old-time hunters have been the forerunners of the white advance throughout all our Western land. Soon after the beginning of the present century they boldly struck out beyond the Mississippi, steered their way across the flat and endless seas of grass, or pushed up the valleys of the great lonely rivers, crossed the passes that wound among the towering peaks of the Rockies, toiled over the melancholy wastes of sage brush and alkali, and at last, breaking through the gloomy woodland that belts the coast, they looked out on the heaving waves of the greatest of all the oceans. They lived for months, often for years, among the Indians, now as friends, now as foes, warring, hunting, and marrying with them; they acted as guides for exploring parties, as scouts for the soldiers who from time to time were sent against the different hostile tribes. At long intervals they came into some frontier settlement or some fur company’s fort, posted in the heart of the wilderness, to dispose of their bales of furs, or to replenish their stock of ammunition and purchase a scanty supply of coarse food and clothing.

From that day to this they have not changed their way of life. But there are not many of them left now. The basin of the Upper Missouri was their last stronghold, being the last great hunting-ground of the Indians, with whom the white trappers were always fighting and bickering, but who nevertheless by their presence protected the game that gave the trappers their livelihood. My cattle were among the very first to come into the land, at a time when the buffalo and beaver still abounded, and then the old hunters were common. Many a time I have hunted with them, spent the night in their smoky cabins, or had them as guests at my ranch. But in a couple of years after the inrush of the cattle-men the last herds of the buffalo were destroyed, and the beaver were trapped out of all the plains’ streams. Then the hunters vanished likewise, save that here and there one or two still remain in some nook or out-of-the-way corner. The others wandered off restlessly over the land,—some to join their brethren in the Coeur d’Aléne or the northern Rockies, others to the coast ranges or to far-away Alaska. Moreover, their ranks were soon thinned by death, and the places of the dead were no longer taken by new recruits. They led hard lives, and the unending strain of their toilsome and dangerous existence shattered even such iron frames as theirs. They were killed in drunken brawls, or in nameless fights with roving Indians; they died by one of the thousand accidents incident to the business of their lives,—by flood or quicksand, by cold or starvation, by the stumble of a horse or a foot slip on the edge of a cliff; they perished by diseases brought on by terrible privation, and aggravated by the savage orgies with which it was varied.

Yet there was not only much that was attractive in their wild, free, reckless lives, but there was also very much good about the men themselves. They were—and such of them as are left still are—frank, bold, and self-reliant to a degree. They fear neither man, brute, nor element. They are generous and hospitable; they stand loyally by their friends, and pursue their enemies with bitter and vindictive hatred. For the rest, they differ among themselves in their good and bad points even more markedly than do men in civilized life, for out on the border virtue and wickedness alike take on very pronounced colors. A man who in civilization would be merely a backbiter becomes a murderer on the frontier; and, on the other hand, he who in the city would do nothing more than bid you a cheery good-morning, shares his last bit of sun-jerked venison with you when threatened by starvation in the wilderness. One hunter may be a dark-browed, evil-eyed ruffian, ready to kill cattle or run off horses without hesitation, who if game fails will at once, in Western phrase, “take to the road,”—that is, become a highwayman. The next is perhaps a quiet, kindly, simple-hearted man, law-abiding, modestly unconscious of the worth of his own fearless courage and iron endurance, always faithful to his friends, and full of chivalric and tender loyalty to women.

The hunter is the arch-type of freedom. His well-being rests in no man’s hands save his own. He chops down and hews out the logs for his hut, or perhaps makes merely a rude dug-out in the side of a hill, with a skin roof, and skin flaps for the door. He buys a little flour and salt, and in times of plenty also sugar and tea; but not much, for it must all be carried hundreds of miles on the backs of his shaggy pack-ponies. In one corner of the hut, a bunk covered with deer-skins forms his bed; a kettle and a frying-pan may be all his cooking-utensils. When he can get no fresh meat he falls back on his stock of jerked venison, dried in long strips over the fire or in the sun.

Most of the trappers are Americans, but they also include some Frenchmen and half-breeds. Both of the last, if on the plains, occasion ally make use of queer wooden carts, very rude in shape, with stout wheels that make a most doleful squeaking. In old times they all had Indian wives; but nowadays those who live among and intermarry with the Indians are looked down upon by the other frontiersmen, who contemptuously term them “squaw men.” All of them depend upon their rifles only for food and for self-defense, and make their living by trapping, peltries being very valuable and yet not bulky. They are good game shots, especially the pure Americans; although, of course, they are very boastful, and generally stretch the truth tremendously in telling about their own marksmanship. Still they often do very remarkable shooting, both for speed and accuracy. One of their feats, that I never could learn to copy, is to make excellent shooting after nightfall. Of course all this applies only to the regular hunters; not to the numerous pretenders who hang around the outskirts of the towns to try to persuade unwary strangers to take them for guides.

On one of my trips to the mountains I happened to come across several old-style hunters at the same time. Two were on their way out of the woods, after having been all winter and spring without seeing a white face. They had been lucky, and their battered pack-saddles carried bales of valuable furs—fisher, sable, otter, mink, beaver. The two men, though fast friends and allies for many years, contrasted oddly. One was a short, square-built, good-humored Kanuck, always laughing and talking, who interlarded his conversation with a singularly original mixture of the most villainous French and English profanity. His partner was an American, gray-eyed, tall and straight as a young pine, with a saturnine, rather haughty face, and proud bearing. He spoke very little, and then in low tones, never using an oath; but he showed now and then a most unexpected sense of dry humor. Both were images of bronzed and rugged strength. Neither had the slightest touch of the bully in his nature; they treated others with the respect that they also exacted for themselves. They bore an excellent reputation as being not only highly skilled in woodcraft and the use of the rifle, but also men of tried courage and strict integrity, whose word could be always implicitly trusted.

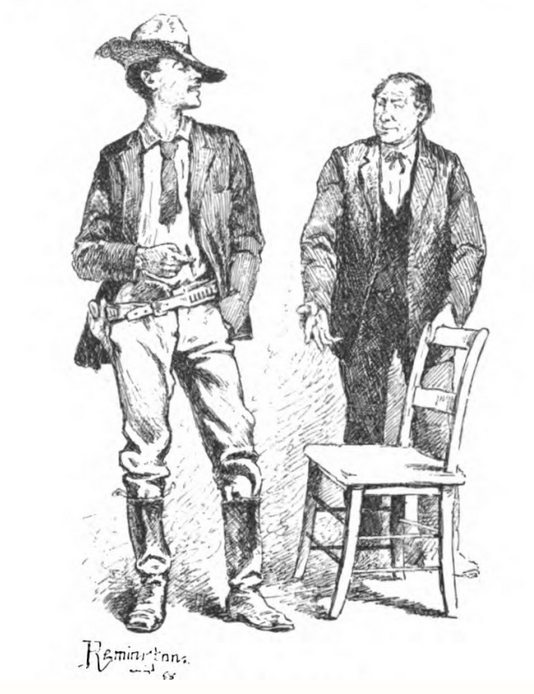

I had with me at the time a hunter who, though their equal as marks man or woodsman, was their exact opposite morally. He was a pleasant companion and useful assistant, being very hard-working, and possessing a temper that never was ruffled by anything. He was also a good-looking fellow, with honest brown eyes; but he no more knew the difference between right and wrong than Adam did before the fall. Had he been at all conscious of his wickedness, or had he possessed the least sense of shame, he would have been unbearable as a companion; but he was so perfectly pleas ant and easy, so good-humoredly tolerant of virtue in others, and he so wholly lacked even a glimmering suspicion that murder, theft, and adultery were matters of anything more than individual taste, that I actually grew to be rather fond of him. He never related any of his past deeds of wickedness as matters either for boastfulness or for regret; they were simply repeated incidentally in the course of conversation. Thus once, in speaking of the profits of his different enterprises, he casually mentioned making a good deal of money as a Government scout in the South-west by buying cartridges from some negro troops at a cent apiece and selling them to the hostile Apaches for a dollar each. His conduct was not due to sympathy with the Indians, for it appeared that later on he had taken part in massacring some of these same Apaches when they were prisoners. He brushed aside as irrelevant one or two questions which I put to him : matters of sentiment were not to be mixed up with a purely mercantile speculation. Another time we were talking of the curious angles bullets sometimes fly off at when they ricochet. To illustrate the matter be related an experience which I shall try to give in his own words. “One time, when I was keeping a saloon down in New Mexico, there was a man owed me a grudge. Well, he took sick of the small-pox, and the doctor told him he’d sure die, and he said if that was so he reckoned he’d kill me first. So he come a-riding in with his gun [in the West a revolver is generally called a gun] and begun shooting; but I hit him first, and away he rode. I started to get on my horse to follow him; but there was a little Irishman there who said he’d never killed a man, and he begged hard for me to give him my gun and let him go after the other man and finish him. So I let him go; and when he caught up, blamed if the little cuss didn’t get so nervous that he fired off into the ground, and the darned bullet struck a crowbar, and glanced up, and hit the other man square in the head and killed him! Now, that was a funny shot, wasn’t it?”

The fourth member of our party round the camp-fire that night was a powerfully built trapper, partly French by blood, who wore a gaily colored capote, or blanket-coat, a greasy fur cap, and moccasins. He had grizzled hair, and a certain uneasy, half-furtive look about the eyes. Once or twice he showed a curious reluctance about allowing a man to approach him suddenly from behind. Altogether his actions were so odd that I felt some curiosity to learn his history. It turned out that he had been through a rather uncanny experience the winter before. He and another man had gone into a remote basin, or inclosed valley, in the heart of the mountains, where game was very plentiful; indeed, it was so abundant that they decided to pass the winter there. Accordingly they put up a log-cabin, working hard, and merely killing enough meat for their immediate use. Just as it was finished winter set in with tremendous snow-storms. Going out to hunt, in the first lull, they found, to their consternation, that every head of game had left the valley. Not an animal was to be found therein; they had abandoned it for their winter haunts. The outlook for the two adventurers was appalling. They were afraid of trying to break out through the deep snow-drifts, and starvation stared them in the face if they staid. The man I met had his dog with him. They put themselves on very short commons, so as to use up their flour as slowly as possible, and hunted unweariedly, but saw nothing. Soon a violent quarrel broke out between them. The other man, a fierce, sullen fellow, insisted that the dog should be killed, but the owner was exceedingly attached to it, and refused. For a couple of weeks they spoke no word to each other, though cooped in the little narrow pen of logs. Then one night the owner of the dog was wakened by the animal crying out; the other man had tried to kill it with his knife, but failed. The pro visions were now almost exhausted, and the two men were glaring at each other with the rage of maddened, ravening hunger. Neither dared to sleep, for fear that the other would kill him. Then the one who owned the dog at last spoke, and proposed that, to give each a chance for his life, they should separate. He would take half of the handful of flour that was left and start off to try to get home; the other should stay where he was; and if he tried to follow the first, he was warned that he would be shot without mercy. A like fate was to be the portion of the wanderer If driven to return to the hut. The arrangement was agreed to and the two men separated, neither daring to turn his back while they were within rifle shot of each other. For two days the one who went off toiled on with weary weakness through the snow-drifts. Late on the second afternoon, as he looked back from a high ridge, he saw in the far distance a black speck against the snow, coming along on his trail. His companion was dogging his footsteps. Immediately he followed his own trail back a little and lay in ambush. At dusk his companion came stealthily up, rifle in hand, peering cautiously ahead, his drawn face showing the starved, eager ferocity of a wild beast, and the man he was hunting shot him down exactly as if he had been one. Leaving the body where it fell, the wanderer continued his journey, the dog staggering painfully behind him. The next evening he baked his last cake and divided it with the dog. In the morning, with his belt drawn still tighter round his skeleton body, he once more set out, with apparently only a few hours of dull misery between him and death. At noon he crossed the track of a huge timber wolf; instantly the dog gave ‘tongue, and, rallying its strength, ran along the trail. The man struggled after. At last his strength gave out and he sat down to die; but while sitting still, slowly stiffening with the cold, he heard the dog baying in the woods. Shaking off his mortal numbness, he crawled towards the sound, and found the wolf over the body of a deer that he had just killed, and keeping the dog from it. At the approach of the new assailant the wolf sullenly drew off, and man and dog tore the raw deer-flesh with hideous eagerness. It made them very sick for the next twenty-four hours; but, lying by the carcass for two or three days, they recovered strength. A week afterwards the trapper reached a miner’s cabin in safety. There he told his tale, and the unknown man who alone might possibly have contradicted it lay dead in the depths of the wolf-haunted forest.

The cowboys, who have supplanted these old hunters and trappers as the typical men of the plains, themselves lead lives that are almost as full of hardship and adventure. The unbearable cold of winter sometimes makes the small outlying camps fairly uninhabitable if fuel runs short; and if the line riders are caught in a blizzard while making their way to the home ranch, they are lucky if they get off with nothing worse than frozen feet and faces.

They are, in the main, hard-working, faithful fellows, but of course are frequently obliged to get into scrapes through no fault of their own. Once, while out on a wagon trip, I got caught while camped by a spring on the prairie, through my horses all straying. A few miles off was the camp of two cowboys, who were riding the line for a great Southern cow-outfit. I did not even know their names, but happening to pass by them I told of my loss, and the day after they turned up with the missing horses, which they had been hunting for twenty-four hours. All I could do in return was to give them some reading matter—something for which the men in these lonely camps are always grateful. Afterwards I spent a day or two with my new friends, and we became quite intimate. They were Texans. Both were quiet, clean-cut, pleasant-spoken young fellows, who did not even swear, except under great provocation,— and there can be no greater provocation than is given by a “mean” horse or a refractory steer. Yet, to my surprise, I found that they were, in a certain sense, fugitives from justice. They were complaining of the extreme severity of the winter weather, and mentioned their longing to go back to the South. The reason they could not was that the summer before they had taken part in a small civil war in one of the wilder counties of New Mexico. It had originated in a quarrel between two great ranches over their respective water rights and range rights,—- a quarrel of a kind rife among pastoral peoples since the days when the herdsmen of Lot and Abraham strove together for the grazing lands round the mouth of the Jordan. There were collisions between bands of armed cowboys, the cattle were harried from the springs, outlying camps were burned down, and the sons of the rival owners fought each other to the death with bowie-knife and revolver when they met at the drinking-booths of the squalid towns. Soon the smoldering jealousy which is ever existent between the Americans and Mexicans of the frontier was aroused, and when the original cause of quarrel was adjusted, a fierce race struggle took its place. It was soon quelled by the arrival of a strong sheriff’s posse and the threat of interference by the regular troops, but not until after a couple of affrays, each attended with bloodshed. In one of these the American cowboys of a certain range, after a brisk fight, drove out the Mexican vaqueros from among them. In the other, to avenge the murder of one of their number, the cowboys gathered from the country round about and fairly stormed the “ Greaser ” (that is, Mexican) village where the murder had been committed, killing four of the inhabitants. My two friends had borne a part in this last affair. They were careful to give a rather cloudy account of the details, but I gathered that one of them was “wanted” as a participant, and the other as a witness.

However, they were both good fellows, and probably their conduct was justifiable, at least according to the rather fitful lights of the border. Sitting up late with them, around the sputtering fire, they became quite confidential. At first our conversation touched only the usual monotonous round of subjects worn threadbare in every cow-camp. A bunch of steers had been seen traveling over the scoria buttes to the head of Elk Creek; they were mostly Texan doughgies (a name I have never seen written; it applies to young immigrant cattle), but there were some of the Hash-Knife four-year olds among them. A stray horse with a blurred brand on the left hip had just joined the bunch of saddle-ponies. The red F. V. cow, one of whose legs had been badly bitten by a wolf, had got mired down in an alkali spring, and when hauled out had charged upon her rescuer so viciously that he barely escaped. The old mule, Sawback, was getting over the effects of the rattlesnake bite. The river was going down, but the fords were still bad, and the quicksand at the Custer Trail crossing had worked along so that wagons had to be taken over opposite the blasted cottonwood. One of the men had seen a Three-Seven-B rider who had just left the Green River round-up, and who brought news that they had found some cattle on the reservation, and were now holding about twelve hundred head on the big brushy bottom below Rainy Butte. Bronco Jim, our local flash rider, had tried to ride the big, bald-faced sorrel belonging to the Oregon horse outfit, and had been bucked off and his face smashed in. This piece of information of course drew forth much condemnation of the unfortunate Jim’s equestrian skill. It was at once agreed that he “wasn’t the sure enough bronco-buster he thought himself,” and he was compared very unfavorably to various heroes of the quirt and spurs who lived in Texas and Colorado; for the best rider, like the best hunter, is invariably either dead or else a resident of some other district.

These topics having been exhausted, we discussed the rumor that the vigilantes had given notice to quit to two men who had just built a shack at the head of the Little Dry, and whose horses included a suspiciously large number of different brands, most of them blurred. Then our conversation became more personal, and they asked if I would take some letters to post for them. Of course I said yes, and two letters—evidently the product of severe manual labor—were produced. Each was directed to a girl; and my companions, now very friendly, told me that they both had sweethearts, and for the next hour I listened to a full account of their charms and virtues.

But it is not often that plainsmen talk so freely. They are rather reserved, especially to strangers; and are certain to look with dislike on any man who, when they first meet him, talks a great deal. It is always a good plan, if visiting a strange camp or ranch, to be as silent as possible.

Another time, at a ranch not far from my own, I found among the cow boys gathered for the round-up two Bible-reading Methodists. They were as straitlaced as any of their kind, but did not obtrude their opinions on anyone else, and were first-class workers, so that they had no trouble with the other men. Associated with them were two or three blear-eyed, slit-mouthed ruffians, who were as loose of tongue as of life.

Generally some form of stable government is provided for the counties as soon as their population has become at all fixed, the frontiersmen showing their national aptitude for organization. Then lawlessness is put down pretty effectively. For example, as soon as we organized the government of Medora—an excessively unattractive little hamlet, the county seat of our huge, scantily settled county—we elected some good officers, built a log jail, prohibited all shooting in the streets, and enforced the prohibition, etc., etc.

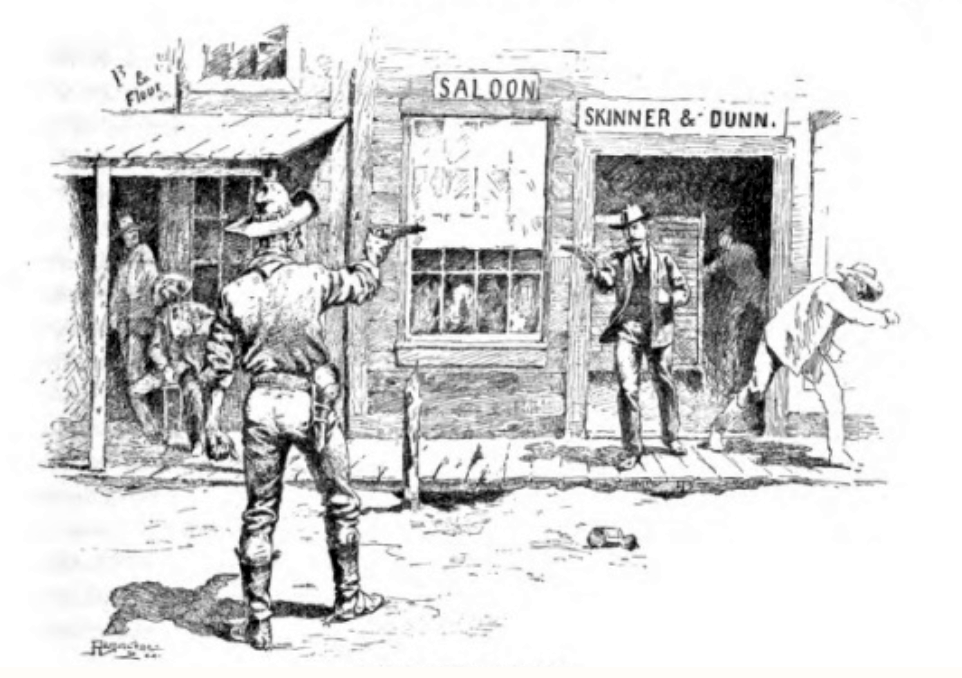

Up to that time there had been a good deal of lawlessness of one kind or another, only checked by an occasional piece of individual retribution or by a sporadic outburst of vigilance committee work. In such a society the desperadoes of every grade flourish. Many are merely ordinary rogues and swindlers, who rob and cheat on occasion, but are dangerous only when led by some villain of real intellectual power. The gambler, with hawk eyes and lissome fingers, is scarcely classed as a criminal; indeed, he may be a very public-spirited citizen. But as his trade is so often plied in saloons, and as even if, as sometimes happens, he does not cheat, many of his opponents are certain to attempt to do so, he is of necessity obliged to be skillful and ready with his weapon, and gambling rows are very common. Cowboys lose much of their money to gamblers; it is with them hard come and light go, for they exchange the wages of six months’ grinding toil and lonely peril for three days’ whooping carousal, spending their money on poisonous whisky or losing it over greasy cards in the vile dance-houses. As already explained, they are in the main good men; and the disturbance they cause in a town is done from sheer rough light-heartedness. They shoot off boot-heels or tall hats occasionally, or make some

obnoxious butt “dance” by shooting round his feet; but they rarely meddle in this way with men who have not themselves played the fool. A fight in the streets is almost always a duel between two men who bear each other malice; it is only in a general mélée in a saloon that outsiders often get hurt, and then it is their own fault, for they have no business to be there. One evening at Medora a cowboy spurred his horse up the steps of a rickety “hotel” piazza into the bar-room, where he began firing at the clock, the decanters, etc., the bartender meanwhile taking one shot at him, which missed. When he had emptied his revolver he threw down a roll of bank-notes on the counter, to pay for the damage he had done, and galloped his horse out through the door, disappearing in the darkness with loud yells to a rattling accompaniment of pistol shots interchanged between himself and some passer-by who apparently began firing out of pure desire to enter into the spirit of the occasion,— for it was the night of the Fourth of July, and all the country round about had come into town for a spree.

All this is mere horse-play; it is the cowboy’s method of “painting the town red,” as an interlude in his harsh, monotonous life. Of course there are plenty of hard characters among cowboys, but no more than among lumbermen and the like; only the cowboys are so ready with their weapons that a bully in one of their camps is apt to be a murderer instead of merely a bruiser. Often, moreover, on a long trail, or in a far-off camp, where the men are for many months alone, feuds spring up that are in the end sure to be slaked in blood. As a rule, however, cowboys who become desperadoes soon perforce drop their original business, and are no longer employed on ranches, unless in counties or territories where there is very little heed paid to the law, and where, in consequence, a cattle-owner needs a certain number of hired bravos. Until within two or three years this was the case in parts of Arizona and New Mexico, where land claims were “jumped” and cattle stolen all the while, one effect being to insure high wages to every individual who combined murderous proclivities with skill in the use of the six-shooter.

Even in much more quiet regions different outfits vary greatly as regards the character of their employees: I know one or two where the men are good ropers and riders, but a gambling, brawling, hard-drinking set, always shooting each other or strangers. Generally, in such a case, the boss is himself as objectionable as his men; he is one of those who have risen by unblushing rascality, and is always sharply watched by his neighbors, because he is sure to try to shift calves on to his own cows, to brand any blurred animal with his own mark, and perhaps to attempt the alteration of perfectly plain brands. The last operation, however, has become very risky since the organization of the cattle country, and the appointment of trained brand-readers as inspectors. These inspectors examine the hide of every animal slain, sold, or driven off, and it is wonderful to see how quickly one of them will detect any signs of a brand having been tampered with. Now there is, in consequence, very little of this kind of dishonesty, whereas formerly herds were occasionally stolen almost bodily.

Claim-jumpers are, as a rule, merely blackmailers. Sometimes they will by threats drive an ignorant foreigner from his claim, but never an old frontiersman. They delight to squat down beside ranchmen who are themselves trying to keep land to which they are not entitled, and who therefore know that their only hope is to bribe or to bully the intruder.

Cattle-thieves, for the reason given above, are not common, although there are plenty of vicious, shiftless men who will kill a cow or a steer for the meat in winter, if they get a chance.

Horse-thieves, however, are always numerous and formidable on the frontier; though in our own country they have been summarily thinned out of late years. It is the fashion to laugh at the severity with which horse-stealing is punished on the border, but the reasons are evident Horses are the most valuable property of the frontiersman, whether cow boy, hunter, or settler, and are often absolutely essential to his well-being, and even to his life. They are always marketable, and they are very easily stolen, for they carry themselves off, instead of having to be carried. Horse-stealing is thus a most tempting business, especially to the more reckless ruffians, and it is always followed by armed men; and they can only be kept in check by ruthless severity. Frequently they band together with the road agents (highwaymen) and other desperadoes into secret organizations, which control and terrorize a district until overthrown by force. After the civil war a great many guerrillas, notably from Arkansas and Missouri, went out to the plains, often drifting northward. They took naturally to horse-stealing and kindred pursuits. Since I have been in the northern cattle country I have known of half a dozen former members of Quantrell’s gang being hung or shot.

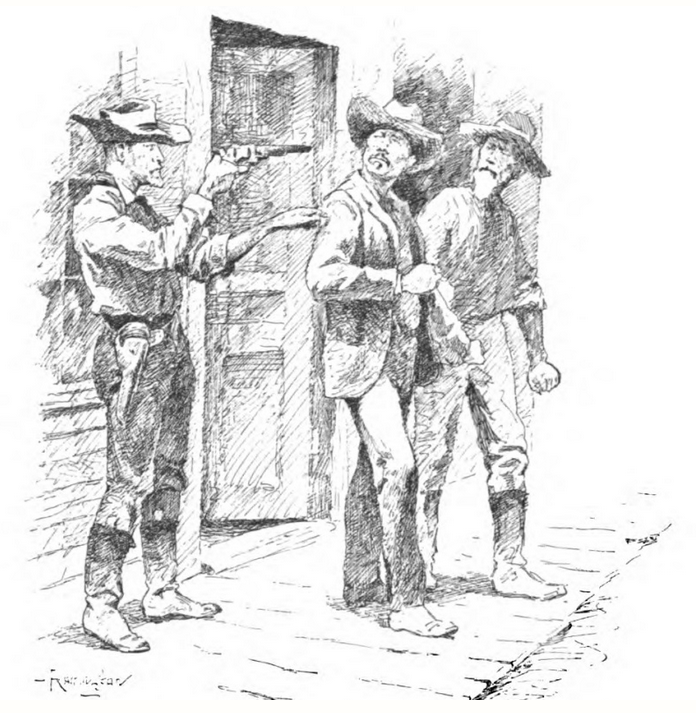

The professional man-killers, or “bad men,” may be horse-thieves or highwaymen, but more often are neither one nor the other. Some of them, like some of the Texan cowboys, become very expert in the use of the revolver, their invariable standby; but in the open a cool man with a rifle is always an overmatch for one of them, unless at very close quarters, on account of the superiority of his weapon. Some of the “bad men” are quiet, good fellows, who have been driven into their career by accident. One of them has perhaps at some time killed a man in self-defense; he acquires some reputation, and the neighboring bullies get to look on him as a rival whom it would be an honor to slay; so that from that time on he must be ever on the watch, must learn to draw quick and shoot straight, —the former being even more important than the latter,—and probably has to take life after life in order to save his own.

Some of these men are brave only because of their confidence in their own skill and strength; once convince them that they are overmatched and they turn into abject cowards. Others have nerves of steel and will face any odds, or certain death itself, without flinching a hands breadth. I was once staying in a town where a desperately plucky fight took place. A noted desperado, an Arkansas man, had become involved in a quarrel with two others of the same ilk, both Irishmen and partners. For several days all three lurked about the saloon-infested streets of the roaring little board-and-canvas “city,” each trying to get “the drop,”—— that is, the first shot,— the other inhabitants looking forward to the fight with pleased curiosity, no one dreaming of interfering. At last one of the partners got a chance at his opponent as the latter was walking into a gambling hell, and broke his back near the hips; yet the crippled, mortally wounded man twisted around as he fell and shot his slayer dead. Then, knowing that he had but a few moments to live, and expecting that his other foe would run up on hearing the shooting, he dragged himself by his arms out into the street; immediately afterwards, as he anticipated, the second partner appeared, and was killed on the spot. The victor did not live twenty minutes. As in most of these encounters, all of the men who were killed deserved their fate. In my own not very extensive experience I can recall but one man killed in these fights whose death was regretted, and he was slain by a European. Generally everyone is heartily glad to hear of the death of either of the contestants, and the only regret is that the other survives.

One curious shooting scrape that took place in Medora was worthy of being chronicled by Bret Harte. It occurred in the summer of 1884, I believe, but it may have been the year following. I did not see the actual occurrence, but I saw both men immediately afterwards; and I heard the shooting, which took place in a saloon on the bank, while I was swimming my horse across the river, holding my rifle up so as not to wet it. I will not give their full names, as I am not certain what has become of them; though I was told that one had since been either put in jail or hung, I forget which. One of them was a saloon-keeper, familiarly called Welshy. The other man, Hay, had been bickering with him for some time. One day Hay, who had been defeated in a wrestling match by one of my own boys, and was out of temper, entered the other’s saloon, and became very abusive. The quarrel grew more and more violent, and suddenly Welshy whipped out his revolver and blazed away at Hay. The latter staggered slightly, shook himself, stretched out his hand, and gave back to his would be slayer the ball, saying, “ Here, man, here’s the bullet.” It had glanced along his breast-bone, gone into the body, and come out at the point of the shoulder, when, being spent, it dropped down the sleeve into his hand. Next day the local paper, which rejoiced in the title of “The Bad Lands Cowboy,” chronicled the event in the usual vague way as an “unfortunate occurrence” between “two of our most esteemed fellow citizens.” The editor was a good fellow, a college graduate, and a first class base-ball player, who always stood stoutly up against any corrupt dealing; but, like all other editors in small Western towns, he was intimate with both combatants in almost every fight.

The winter after this occurrence I was away, and on my return began asking my foreman—a particular crony of mine—about the fates of my various friends. Among others I inquired after a traveling preacher who had come to our neighborhood; a good man, but irascible. After a moment’s pause a gleam of remembrance came into my informant’s eye: “Oh, the parson! Well—he beat a man over the head with an ax, and they put him in jail!” It certainly seemed a rather summary method of re— pressing a refractory parishioner. Another acquaintance had shared a like doom. “He started to go out of the country, but they ketched him at Bismarck and put him in jail “—apparently on general principles, for I did not hear of his having committed any specific crime. My foreman sometimes developed his own theories of propriety. I remember his objecting strenuously to a proposal to lynch a certain French-Canadian who had lived in his own cabin, back from the river, ever since the whites came into the land, but who was suspected of being a horse-thief. His chief point against the proposal was, not that the man was innocent, but that “it didn’t seem anyways right to hang a man who had been so long in the country.”

Sometimes we had a comic row. There was one huge man from Missouri called “The Pike,” who had been the keeper of a wood-yard for steamboats on the Upper Missouri. Like most of his class he was a hard case, and, though pleasant enough when sober, always insisted on fighting when drunk. One day, when on a spree, he announced his intention of thrashing the entire population of Medora seriatim[1], and began to make his promise good with great vigor and praiseworthy impartiality. He was victorious over the first two or three eminent citizens whom he encountered, and then tackled a gentleman known as “Cold Turkey Bill.” Under ordinary circumstances Cold Turkey, though an able-bodied man, was no match for The Pike; but the latter was still rather drunk, and moreover was wearied by his previous combats. So Cold Turkey got him down, lay on him, choked him by the throat with one hand, and began pounding his face with a triangular rock held in the other. To the onlookers the fate of the battle seemed decided; but Cold Turkey better appreciated the endurance of his adversary, and it soon appeared that he sympathized with the traditional hunter who, having caught a wildcat, earnestly besought a comrade to help him let it go. While still pounding vigorously he raised an agonized wail: “Help me off, fellows, for the Lord’s sake; he’s tiring me out!” There was no resisting so plaintive an appeal, and the bystanders at once abandoned their attitude of neutrality for one of armed intervention.

I have always been treated with the utmost courtesy by all cowboys, whether on the round-up or in camp; and the few real desperadoes I have seen were also perfectly polite. Indeed, I never was shot at maliciously but once. This was on an occasion when I had to pass the night in a little frontier hotel where the bar-room occupied the whole lower floor, and was in consequence the place where everyone, drunk or sober, had to sit. My assailant was neither a cowboy nor a bona fide “bad man,” but a broad-hatted ruffian of cheap and commonplace type, who had for the moment terrorized the other men in the bar-room, these being mostly sheep-herders and small grangers. The fact that I wore glasses, together with my evident desire to avoid a fight, apparently gave him the impression—a mistaken one—that I would not resent an injury.

The first deadly affray that took place in our town, after the cattle-men came in and regular settlement began, was between a Scotchman and a Minnesota man, the latter being one of the small stockmen. Both had “shooting ” records, and each was a man with a varied past. The Scotch man, a noted bully, was the more daring of the two, but he was much too hot-headed and overbearing to be a match for his gray-eyed, hard-featured foe. After a furious quarrel and threats of violence, the Scotchman mounted his horse, and, rifle in hand, rode to the door of the mud ranch, perched on the brink of the river-bluff, where the American lived, and was instantly shot down by the latter from behind a corner of the building.

Later on I once opened a cowboy ball with the wife of the victor in this contest, the husband himself dancing opposite. It was the lanciers, and he knew all the steps far better than I did. He could have danced a minuet very well with a little practice. The scene reminded one of the ball where Bret Harte’s heroine “danced down the middle with the man who shot Sandy Magee.”

But though there were plenty of men present each of whom had shot his luckless Sandy Magee, yet there was no Lily of Poverty Flat. There is an old and true border saying that “the frontier is hard on women and cattle.” There are some striking exceptions; but, as a rule, the grinding toil and hardship of a life passed in the wilderness, or on its outskirts, drive the beauty and bloom from a woman’s face long before her youth has left her. By the time she is a mother she is sinewy and angular, with thin, compressed lips and furrowed, sallow brow. But she has a hundred qualities that atone for the grace she lacks. She is a good mother and a hard-working housewife, always putting things to rights, washing and cooking for her stalwart spouse and offspring. She is faithful to her husband, and, like the true American that she is, exacts faithfulness in return. Peril cannot daunt her, nor hardship and poverty appall her. Whether on the mountains in a log hut chinked with moss, in a sod or adobe hovel on the, desolate prairie, or in a mere temporary camp, where the white-topped wagons have been drawn up in a protection-giving circle near some spring, she is equally at home. Clad in a dingy gown and a hideous sun-bonnet she goes bravely about her work, resolute, silent, uncomplaining. The children grow up pretty much as fate dictates. Even when very small they seem well able to protect themselves. The wife of one of my teamsters, who lived in a small outlying camp, used to keep the youngest and most troublesome members of her family out of mischief by the simple expedient of picketing them out, each child being tied by the leg, with a long leather string, to a stake driven into the ground, so that it could neither get at another child nor at anything breakable.

The best buckskin maker I ever met was, if not a typical frontierswoman, at least a woman who could not have reached her full development save on the border. She made first-class hunting-shirts, leggins, and gauntlets. When I knew her she was living alone in her cabin on mid prairie, having dismissed her husband six months previously in an exceedingly summary manner. She not only possessed redoubtable qualities of head and hand, but also a nice sense of justice, even towards Indians, that is not always found on the frontier. Once, going there for a buckskin shirt, I met at her cabin three Sioux, and from their leader, named One Bull, purchased a tobacco-pouch, beautifully worked with porcupine quills. She had given them some dinner, for which they had paid with a deer hide. Falling into conversation, she mentioned that just before I came up a white man, apparently from Deadwood, had passed by, and had tried to steal the Indians’ horses. The latter had been too quick for him, had run him down, and brought him back to the cabin. “I told ’em to go right on and hang him, and I wouldn’t never cheep about it,” said my informant; “but they let him go, after taking his gun. There ain’t no sense in stealing from Indians any more than from white folks, and I’m not going to have it round my ranch, neither. There! I‘ll give ’em back the deer-hide they give me for the dinner and things, anyway.” I told her I sincerely wished we could make her sheriff and Indian agent. She made the Indians -—and whites, too, for that matter—behave themselves and walk the straightest kind of line, not tolerating the least symptom of rebellion; but she had a strong natural sense of justice.

The cowboy balls, spoken of above, are always great events in the small towns where they take place, being usually given when the round up passes near; everybody round about comes in for them. They are almost always conducted with great decorum; no unseemly conduct would be tolerated. There is usually some master of the ceremonies, chosen with due regard to brawn as well as brain. He calls off the figures of the square dances, so that even the inexperienced may get through them, and incidentally preserves order. Sometimes we are allowed to wear our revolvers, and sometimes not. The nature of the band, of course, depends upon the size of the place. I remember one ball that came near being a failure because our half-breed fiddler “went and got himself shot,” as the indignant master of the ceremonies phrased it.

But all these things are merely incidents in the cowboy’s life. It is utterly unfair to judge the whole class by what a few individuals do in the course of two or three days spent in town, instead of by the long months of weary, honest toil common to all alike. To appreciate properly his fine, manly qualities, the wild rough-rider of the plains should be seen in his own home. There he passes his days, there he does his life-work, there, when he meets death, he faces it as he has faced many other evils, with quiet, uncomplaining fortitude. Brave, hospitable, hardy, and adventurous, he is the grim pioneer of our race; he prepares the way for the civilization from before whose face he must himself disappear. Hard and dangerous though his existence is, it has yet a wild attraction that strongly draws to it his bold, free spirit. He lives in the lonely lands where mighty rivers twist in long reaches between the barren bluffs; where the prairies stretch out into billowy plains of waving grass, girt only by the blue horizon,—plains across whose endless breadth he can steer his course for days and weeks and see neither man to speak to nor hill to break the level; where the glory and the burning splendor of the sunsets kindle the blue vault of heaven and the level brown earth till they merge together in an ocean of flaming fire.

_______________________

[1] Latin for “in series,” i.e., one man at a time.

Grew up near Tombstone Arizona. You could still find lonely graves in the middle of nowhere, who died from Apache attack, accidents, robbery, etc. Frontier life was hard.