Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Alfred to Victoria: Hands Across a Thousand Years, by George Eayrs (published 1902). All spelling in the original.

Three great features mark the history of the period succeeding that of the Norman Conquest of England: the Crusades, the Orders of Knighthood or Chivalry, and the Monastic Orders. The Crusades, religious wars for the deliverance of the holy places of Christianity from the control of the infidel, set all Europe wandering. They accorded with and developed the spirit of the time. “Over the whole continent of Europe,” says Dr. Jessopp, “the people seem to have had no homes; the merchant, the student, the ecclesiastic were always on the move.” Even the healthy nature of childhood was bewitched. In 1212 thousands of French and German boys started pell-mell for the Holy Land. The results of the Crusades on warfare, manners, commerce, learning, and religion were almost incalculable. Deus vult, “God wills it,” cried the people in answer to the call of Peter the Hermit. Hallam assures us that “this cry affords at once the most obvious and the most certain explanation of the leading principles of the Crusades.” Closely connected with the Crusades, and in itself deeply influential, was the institution known by the general name of Chivalry. Its knights were sworn —

The Knightly Orders were marked off from the common people. They “nursed the evil spirits of pride and revenge, and a high disdain of peaceful arts and industry.” Happily, they were pledged to loyalty, courtesy, and munificence. Loyalty helped to make a man’s “honour” his strongest bond; courtesy softened the treatment of prisoners and set the high pattern of “a gentleman”; while munificence encouraged the hearty generosity and hospitality associated with many noble families to this day. The rise and spread of the mediaeval monastic orders was, however, the most remarkable feature of their age. Appealing to an instinct which has manifested itself in every age, monasticism now acquired vigour, dimensions, and importance unknown before or since. Leaving war and work, tillage and handicraft, no insignificant number of the wealthy and learned inhabitants of Europe immured themselves within the walls of monasteries. There they engaged in religious exercises, cultivated their estates, copied the literary treasures of Greece and Rome, instructed the children, and notwithstanding many shortcomings, rendered some, if by no means adequate, service to their generation and its successors. By the Friars the religious fervour which had carried men and women into the monasteries was directed to the businesses and bosoms of men. Monasticism deeply and widely affected national character, its ideals, and its subsequent development. And nowhere was this the case more than in England.

The Knightly Orders were marked off from the common people. They “nursed the evil spirits of pride and revenge, and a high disdain of peaceful arts and industry.” Happily, they were pledged to loyalty, courtesy, and munificence. Loyalty helped to make a man’s “honour” his strongest bond; courtesy softened the treatment of prisoners and set the high pattern of “a gentleman”; while munificence encouraged the hearty generosity and hospitality associated with many noble families to this day. The rise and spread of the mediaeval monastic orders was, however, the most remarkable feature of their age. Appealing to an instinct which has manifested itself in every age, monasticism now acquired vigour, dimensions, and importance unknown before or since. Leaving war and work, tillage and handicraft, no insignificant number of the wealthy and learned inhabitants of Europe immured themselves within the walls of monasteries. There they engaged in religious exercises, cultivated their estates, copied the literary treasures of Greece and Rome, instructed the children, and notwithstanding many shortcomings, rendered some, if by no means adequate, service to their generation and its successors. By the Friars the religious fervour which had carried men and women into the monasteries was directed to the businesses and bosoms of men. Monasticism deeply and widely affected national character, its ideals, and its subsequent development. And nowhere was this the case more than in England.

These three movements powerfully affected Francis of Assisi, and in turn are vividly represented by him. In him was the Crusader’s love of adventure and wandering. He went himself to convert the Sultan. He was also “a veray parfit gentil knight,” who chose the Lady Poverty for his love, and was ever inviolably true to her. His followers were called “The camp and army of the Knights of God.” And in him and his Order the religious fervour of Monasticism expressed itself, not in seclusion from the world, but in efforts to satisfy its deepest needs and daily wants. To know Francis is to know his time at its best.

Francis Bernardone, son of Pietro Bernardone, and his wife, Madonna Pica, was born in 1182, in the little Italian town of Assisi. George Eliot says truly, “The mill-streams that drive the clappers of the world arise in solitary places.” His father was a wealthy merchant, when merchants not only bought and sold commodities, but were travellers, bankers, news agents, and propagandists. He intended Francis to follow the same calling, and until the age of twenty-four he did so. His service was, however, fitful and half-hearted. Whether as cause or effect of his adopted name — his baptismal name was Giovanni — he loved the French tongue, and French finery and parade. His nature was highly emotional and excitable, even ecstatic, and the fantastic Troubadours found in him a ready follower. Becoming the leader of wild and gay companions, he outstripped them in all kinds of foolish pranks and excesses, and even more in his abounding charities to the poor. At twenty-two he was taken prisoner while defending the walls of the city. Through all his vagaries he carried with him, like Joseph of old, dreams of coming greatness. “You will see that one day I will be adored by the whole world.” Oracles have often been fulfilled in ways least expected by those who uttered them. A great sickness gave him a pause; but convalescence saw him trying pleasure again. He sought to realise his dreams by accompanying a knight to the wars. As they journeyed, sickness again laid Francis low. “Francesco, why do you leave the master for the servant, and the prince for the follower ?” asked an unseen speaker. It was the voice of God to him, and by it he was moved to return to his own land. “There,” added the heavenly voice, “it shall be told you what to do.” There he met Pleasure and her charms, and once again yielded. But not for long. One night he and his band of revellers flung out to finish their wild singing and laughter in the quiet streets of Assisi. Like another Saul of Tarsus, he was suddenly arrested by an unseen power. The majesty of night about him, the stately glory of the dark blue heavens above him, the steady white radiance of their lights, which made his tinselled sceptre of misrule and all his rich bedizenings seem poor and tawdry, fell upon him and abashed his spirit. His companions showered taunts upon him; but his choice was made. He began at once to visit the sick and poor, making lepers his special charge, exchanged his finery for a beggar’s rags, and bestowed his fortune on the church.

A little later (1206), Francis heard the call that determined his momentous public course. He was in the little decaying church of St. Damian, in the suburbs of Assisi, and heard the command, “Restore My church.” Taking the words at first literally, he sold his own and some of his father’s possessions, and laid the proceeds at the feet of the priest of St. Damian. His father was the bitterest of many who opposed what they counted madness. Francis felt, however, the meaning of that word, “Turn thou me, and I shall be turned,” and was insensible to every affection or affliction that would draw or drive him from what he deemed God’s will. Bowing to justice, he restored his father’s property, and renounced all claim upon him. “Henceforward I will only say, ‘ My Father, who art in heaven.’ ” Clothed only with the rough frock of a poor labourer, he went singing through the woods and upon the slopes of the Apennines, rapt in ecstatic communion with Nature and with God, too poor to be robbed, too humble to be offended, spending himself in the lowest service, and relying upon charity for the satisfaction of bare necessities. Returning, he begged the stones with which to repair the church of St. Damian. Another church, Santa Maria, was also restored through his efforts, and became the cradle of the Franciscan Order. He called it the Portiuncula, or little inheritance.

There, in 1208, he received the Rule of his Order. As the priest read, Francis heard the words as never before: “Provide neither gold nor silver, nor brass in your purses, nor scrip for your journey, neither two coats, neither shoes, nor yet staves. And as ye go preach, saying, ‘The kingdom of heaven is at hand.’ ” “This is what I wanted!” Francis cried. He immediately rendered literal obedience; put off his shoes, laid aside his staff, girdle, and purse, and began to preach. Self was completely forgotten in service; tasks the meanest, most repulsive, most exacting, were welcomed: things temporal were as though they were not. Poor, broken, suffering, sinning, struggling humanity was about him, and like his Master, he saved not himself that he might save.

It is well-nigh impossible to credit the historic record of the boundless enthusiasm aroused by Francis. Umbria and other districts of Italy, Spain, Slavonia, Egypt, were the scene of his missionary journeys, and everywhere men’s hearts turned strangely to him. His buoyant poetic nature must be remembered. At rest, and glad at heart in God and His service, his boundless enthusiasm found food everywhere, and communicated itself to all. The universe was at peace with him who was at peace with its Maker. As with our gentle poet Cowper, all creatures were his friends. Birds flocked round him as he preached, and he had greetings for “little sister swallows,” for “Messer Sun, my brother above all,” and for all things in earth, and air, and sky. A characteristic story of Francis reveals in part the source of his power. “Why thee? Why thee? Why thee?” Brother Masseo asked one day, wishing to test the modesty of his leader. “What are you saying?” cried Francis at last. “I am saying that everybody follows thee, everyone desires to see thee, have thee and obey thee, and yet for all that thou art neither beautiful, nor learned, nor of noble family. Whence comes it, then, that it should be thou whom the world desires to follow?” After long contemplation and praising and blessing God, Francis turned towards Masseo and said, “It is because the eye of the Most High has willed it thus; He continually watches the good and the wicked, and as His most holy eyes have not found among sinners any smaller man, nor any more insufficient and more sinful, therefore He hath chosen me to accomplish the marvellous work which God hath undertaken; He chose me because He could find no one more worthless, and He wished to confound the nobility and grandeur, the strength, the beauty, the learning of the world.” Francis was thus conscious of a divine vocation. It made him a leader none might disobey. Innovators had sharp treatment at his hands. He indignantly disowned a monastery that had more than absolute necessaries, and publicly rebuked and caricatured Brother Elias, who wore an easy and elaborate dress. This imperious command of others was made tolerable and even admirable by his own self-abnegation and deep humility, which the story just told reveals. If, however, one would know the deepest explanation of the almost super-human influence of St. Francis, it is found in a poem ascribed to him, and too characteristic to be rejected as unauthentic:

Such devotion compelled imitation. Enthusiasm is contagious. Mazzini says: “After all, there is no call quite so fascinating to men as the call, Come and suffer!” Rachel Winslow, in Mr. Sheldon’s remarkable book, “In His Steps: What would Jesus Do?” cries, “I am hungry to suffer something.” These witnesses are true. It is this, may we not say, divine instinct which explains the heroism of early Christianity, of the Reformation, of Puritanism, of the early Methodists, of the Salvation Army.

Bernardo di Quintavelle was the first follower of Francis: Pietro de Cataneo, the second. In the church of St. Nicholas the three made their appeal to the Scriptures, which, being thrice opened, confirmed and enlarged the Rule given to Francis. “Go, sell all that thou hast, and give to the poor.” “Take nothing for your journey.” “He who will come after Me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross and follow Me.” Sabatier claims that the Calabrian seer, Gioacchino di Fiore, was the spiritual father of Francis, anticipating his principles of voluntary poverty and indifference to secular learning. It is also highly probable that in his work we trace the influence of the Waldenses, the Poor Men of Lyons. When his followers numbered eight, Francis, again in literal imitation of the Lord, sent them out by two and two in four different directions. “‘ Go,’ said our sweet father to his children,” writes Bonaventura, ” ‘ proclaim peace to men; preach repentance for the remission of sins. Be patient in tribulation, watchful in prayer, strong in labour, moderate in speech, grave in conversation, thankful for benefits,’ and he added, ‘ Cast thy care upon the Lord, and He will sustain thee.'” The little band constantly received additions. Clad in a simple tunic, bound with a cord, the gospels their only rule and message, they went everywhere preaching the Word. The results may be described in the words spoken by our Lord of His own work. Few of the words need spiritual interpretation. Never since He ascended had the words been more nearly true: seldom so true of any work since theirs: “The blind receive their sight, and the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, and the poor have the Gospel preached to them.”

That they might the better serve, they retired ever and anon to little hermitages. Ruined cottages and grottoes near the Portiuncula became the places where they obeyed the Lord’s command to His workers, “Come ye yourselves apart and rest awhile.” Their life thus combined the contemplative and the active. They surrounded the Portiuncula and its huts with a quick-set hedge, and it became their first convent. Whether at home or abroad they had their tasks. Francis “never dreamed of creating a mendicant order: he created a labouring order.” He dismissed a follower who refused to work. While they remained true to him his followers were never idle. They often earned their bread by joining in the tasks of those they tried to save, though they did not hesitate to receive a bare subsistence — all they wished — when wholly engaged in things spiritual. Francis insisted that they should be called “The Lesser Brethren,” Minorites, for none could or should be less than they.

In 1212 a similar order was formed for women. With this the name of Santa Clara is indissolubly associated. She was born at Assisi, 1194, and in her pure spirit and utter devotion to Christ, Francis found the reflex and complement of his own. A third order, the Tertiaries, was founded in 1221. Francis well knew that “after all monks and nuns could never form the staple of the human race.” Swayed by the preaching, husbands and wives, affianced youths and maidens, cried out, “What shall we do?” “Remain in your homes,” said Francis, “and I will find you a way of serving God.” The vow exacted was a promise to keep God’s commandments, and avoid vain amusements. They were the Puritans and Methodists of the Middle Ages. Thus those who were involved in secular affairs, or unable to give themselves wholly to the separated life, were associated with the Friars, and followed their Rule as far as might be. Thousands of all classes availed themselves of this institution.

The first chapter of his Order was held in 1215. Provincial ministers (not masters) were appointed for Spain, Provence, France, and Germany. In 1219, at the. second chapter, five thousand brethren were present, and five hundred more were begging admission. Some years earlier, Dominic, a Spaniard of high birth and learning, had founded a preaching order. In 1220 it was conformed to the model of the Franciscans. It differed from it, however, in that while it accepted voluntary poverty, its appeal was to the rich, cultured, and ecclesiastical classes. Formal papal sanction was secured for the Franciscans in 1223.

It was in 1224 that they entered England, the Dominicans having landed two years earlier. They were known as Brethren, Fratres (Freres), which on English lips became “Friars,” and the two Orders were distinguished and called by the colour of their respective habit: the Franciscans, Grey Friars, and the Dominicans, Black Friars. Richard Ingworth, an Englishman, was the leader of the nine penniless Franciscans. Within fifty years they furnished an archbishop for Canterbury. What an England they came to! For eight years our land had been ruled by a boy, Henry III, who ascended the throne when only nine years old: and it is, “Woe to thee, O land, when thy king is a child!” He had followed John, “the meanest, falsest, worst, and wickedest king that ever sat on the throne of England.” For five dark years (1208-1213) an interdict had blighted the land. This was inflicted by Pope Innocent III, because Stephen Langton, whom he had consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury, was not accepted by John. In consequence of the interdict and the frequent use of excommunication by hireling priests, the people had come to do without religion. The marriage bond was lightly broken. The monastic orders were engaged in internecine strife. Many of their most prominent members were selfish and gluttonous, not to say rapacious and wicked. By the beginning of the century the monasteries had been found wanting. Their owners had declined into lawless landlords. Moreover, the monk was drawn as a rule from the gentry class, and was widely separated from the people. The livings were greedily absorbed by the monasteries, and the duties of the priest were left to ignorant, ill-paid hirelings. Preaching was so rare that its effects were said to be almost miraculous. Nearly every high office was filled by a foreigner, who also, by nature, position, and disposition was far removed from the people. Meanwhile the towns were rising into importance, helped by guilds and crafts. The mass-priest, whose fees were his only income, and often his only object, was almost the only reminder there of religion.

Into this darkness the Friars brought their gospel light. Their appeal was to the people. Set discourses — learned, argumentative, speculative — were delivered by the Dominicans. The Franciscans, with simple gospel messages, applied the truth more closely. Francis and his order delighted in “open-air sermons, given in the vulgar tongue, at street corners, in public squares, in the fields.” Often their subject was a story with a moral, brightly, even dramatically told. They were light-hearted and gay, sang the sweet, divine love-songs of their founder, and threw a glad spell over the weary multitudes. The common people heard them gladly. Their message was intensified by their self-sacrifice. They suffered with those they saved. Poorer than the poorest, their food meagre and repulsive, they crowded together to keep warm in fireless hovels, or tramped, two of them together, one behind the other, barefoot, through dust or snow, upon their errands of mercy to the poor, the sick, the loathed, the lost. None but the sick among them might go shod. They were afflicted with diseases resulting from their ministrations and privations, and were despised, hated, and persecuted by the regular clergy. Nor had they reward — except that they “retrieved two generations to the Church, renewed decaying learning, and broke up the rotten conventions of the decrepit hierarchy.” Despite the decline from the simplicity of their Rule, the Friars were the evangelizers of the towns for three centuries. The merchant, the thinker, the unprivileged townsman were their special care. In England especially the laic and popular principles of the Friars were generally prominent. Francis himself was never more than a deacon. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries we find the Friars with the people as against the nobles and the crown. The dumb, oppressed multitude found in them an ear for its sighs and a tongue for its woes. In the latter century the Black Death swept over Europe. No fewer than one hundred and twenty-four thousand Franciscans met death while tending the stricken. England lost one-half her population of three or four millions, but not till thousands of these ministers had laid down their lives in succouring the dwellers in the filthy, undrained towns and the neglected villages.

The physical and spiritual needs of the people were their care. Nor were the mental needs forgotten. Francis himself distrusted secular learning. The habit and one little book were to content his followers. Still, he early admitted learned men to his order. Moreover, the study of the Word and theology inevitably quickened interest in other studies, since, as thinkers know, no question emerges in theology which has not first appeared in philosophy. Besides, his career and his Order rested upon subjective conviction, and not upon objective authority. In his Order we find great formative minds, like Adam de Marsh, Duns Scotus, William of Ockham, and above all, Roger Bacon, by much the most comprehensive and influential scholar of his own day and the centuries either side of him. Through its Franciscan school Oxford became the chief seat of learning of its time at home, and equal to the highest abroad. The Friars were the heralds of the New Learning. Adam de Marsh was the close friend of Grosseteste, who was the precursor of Wycliffe, and the friend of Simon de Montfort. Thus the Franciscan influence is found on the side of freedom for religion, for the mind, for the people.

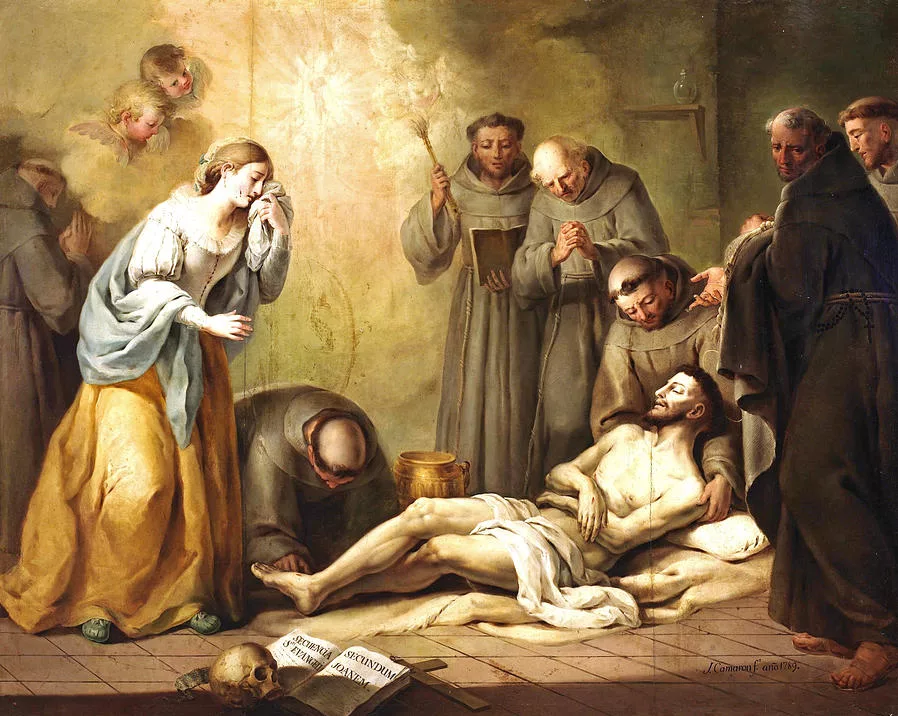

Worn out with labour and hardship, so feeble that he must needs be carried whither he would go to bless and instruct, Francis finished his forty-four years, and welcomed what he called “Sister Death” on October 4, 1226. Two years before he is said to have received miraculously, in his hands and feet and side, the marks (stigmata) of the crucified Lord. If the record be true, the fact makes him no greater; if false, it makes him no less. Only once, if once, did he himself speak of it. Mrs. Oliphant, to whom, as the biographer of Francis, every reader owes a great debt for literary and religious inspiration, voices one’s feelings: “We ask no visionary reverence for the Stigmata, no wondering belief in any miracle. As he stood, he was as great a miracle as any then existing under God’s abundant miraculous heavens; more wonderful than are the day and the night, the sun and the dew; only less wonderful than the great Love which saves the world, and which it was his aim and destiny to reflect and show forth.”