Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Triggernometry: A Gallery of Gunfighters, by Eugene Cunningham (published 1934).

“You won’t come along? Won’t even skip with me, if I hold up the jailer when he opens the door?”

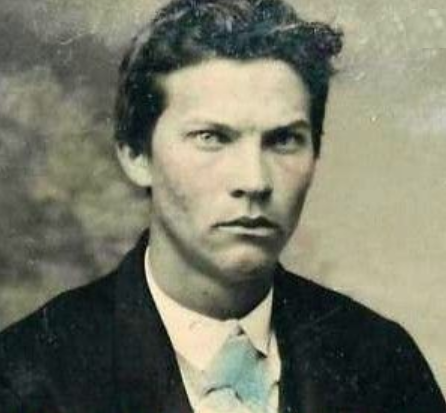

Wes Hardin’s blue eyes shuttled contemptuously from face to face of his cellmates, in the gloom of Longview jail. He twirled an ancient Colt on his forefinger by the trigger-guard. He stared those older jailbirds down.

“Hell! There’s nothing to it! I’ve been in plenty tighter places,” he told them persuasively.

“I—reckon,” a loutish farmer-boy sneered. “Like the time in that Waco barber-shop when you took an’ murdered Huffman. But they landed you here in jail, I notice!”

“You’re a dam’ liar,” Wes said calmly. “Seems that I don’t know half as much about that Waco murder I’m locked up for, as some of you! If I’d killed Huffman, I wouldn’t lie about it! But all your talk’s not covering up your yellow streaks! You haven’t got nerve enough to make a break, even when I take all the risk.”

The other prisoners—all older than Wes Hardin—did not openly resent his manner. He was only seventeen, but he was the best man in that jail. They knew it! Had they known of certain grim incidents of the last two years, in which this preacher’s son had been chief actor, they would have been more respectful still. But they understood him well enough…

“All right, then,” he drawled. “I’ll buy Old Peacemaker, here, from Rufe. I’ll buy John’s new overcoat, too. Forty, gold, for the hogleg. Twenty-five to you, John, for the coat.”

He was counting out the gold when the cell-door rattled. Gold won earlier in that month of January at poker. Won, too, from a man notorious as a flaming daredevil, a gunman of gunmen, famous throughout Texas in 1871—Bill Longley.

Wes’ cellmates popped the money into their pockets. The old Colt Wes had bought—loaded with four .45 cartridges—vanished into his waistband like a sleight of-hand trick. But it was only the old negro woman who served as jail cook. She waddled in through the murk of the winter evening.

“Boss-man say we goin’ lose a boarder, white folks,” she grinned. “Reckon it’s you he means,” she told Wes.

He nodded. Blue eyes narrowed a shade, hardened. That would be better than a jail-break. Nobody took him seriously—at first. His face was too smooth, too boyish. He looked too completely the inexperienced youngster of good family. When the old woman was gone, he made his preparations quickly.

He had two undershirts—he put on both. He pulled on his dress-shirt. Then, by a cord, he suspended the Colt under his left arm. He had a second dress-shirt. He put it on over the weapon. His sack coat and the fur overcoat he had just bought covered the “cutter’s” bulge. So he took off both coats and lay down on his cot. Presently, the door rattled again. It was dark inside the cell.

Stokes was the officer who was to take young Wes Hardin to Waco, to stand trial on the charge of murdering a man named Huffman in a barber-shop. He was a smallish man of forty-five, and the prisoners knew him as a good deal of a bully. He had a lamp. He set it down and crossed to Wes’ cot to shake the boy.

“Up y’ come!” he snapped. “Y’re Waco-bound to git hung. An’ if y’ try any funny business on the road, y’ll wish y’d got hung here! I got a man with me that’s plumb killer!”

Wes trembled artistically as he donned his coats and stuffed the pockets with food. Stokes laughed. So did the other prisoners. But there was a difference—for Stokes was laughing at Wes Hardin and the prisoners were not…

Outside the jail, the earth was heavily blanketed with snow. Stamping there, in the bitter cold, were a big bay gelding, a pretty sorrel mare and a runty black pony wearing only a folded blanket. A wide-shouldered, swarthy man stood at their heads, snarling to himself.

“Say!” Wes Hardin cried, with sight of the black pony. “You can’t come that one on me! Where’s my horse and saddle? The horse I had when you arrested me?”

“Sonny!” Stokes told him sinisterly. “Where y’ goin’, they don’t ride hawses. No, sir! They flap their wings an’ fly! Git onto that pony. Y’ ride it to Waco!”

And the only concession he would make was the getting of one more blanket, for the ride of two hundred twenty-five miles to Waco. Wes’ hands were tied in front of him. His ankles were hobbled under the pony’s belly. The swarthy man, Jim Smolly—quarter-Mex’, quarter nigger, half-white and all bad—cursed Wes venomously for causing him a trip in weather like this. He suggested to Stokes that they go a mile out, shoot the boy and save trouble.

Wes hunched his shoulders and listened. He was almost enjoying himself! They were so sure that they dealt with only a frightened kid. And in this blue-eyed son of Brenham’s old circuit-rider, there ran a streak of bulldog dare-devilry that could not be tamed. He grinned to himself.

He would not be eighteen until May 26. But already he had notches on his guns—eight of them! Billy the Kid came close to amateur status, when compared to John Wesley Hardin, either in number of tallies or in triggernometry!

At fifteen, Hardin had killed a “bad nigger” and, going on the dodge with Yankee troops after him, tallied one white and two black soldiers, ambushing them when they thought to dry-gulch him. For this was “Reconstruction” when nobody but a carpetbagger or a nigger had any rights in the South.

With Simp Dixon, his cold-nerved cousin, Wes had run into another squad of Yankees, down in the tangles of Richland Bottoms. He and Simp each downed one. His sixth man had been a long-haired Arkansas desperado named Bradley, who almost got Wes during a gambling quarrel, but made the fatal mistake of missing.

The seventh man was a roaring big canvasman of the John Robinson show, who “chose” Wes at Horn Hill. Wes was already developing that amazing speed on the draw which was to make his name the all-time symbol of gunplay. He “slapped leather” with the canvasman and left him dead.

Leaving Horn Hill on the jump, Wes had continued his journey homeward, toward Brenham. And wherever young Wes Hardin went, he went “on the prod.” In Texas of 1870, liberally salted with two-fisted, two gunned gentlemen, he was never long out of hot water. He was already a professional gambler. The saloon and the crib were his hangouts.

At Kosse, the gentleman-friend of a Cyprian beauty of the town tried the ancient badger-game on Wes. The boy pretended to be scared to death. He dropped some money on the floor. The “badgerer,” gun in hand, grinned and stooped to pick it up. There was a twinkle of the boy’s hand, a scream from the woman. The man jerked but before his gun could lift there sounded, hollow in that little room, the roar of a .45. The man fell with a bullet-hole in his forehead.

It was Wes’ boast now, as it remained for many a year, that he took “no sass but sassparilla!”

And this was the smooth-faced, frightened, helpless boy, whom those two thickwitted, bullying officers were carrying to Waco!

They huddled close together, leaving Longview, bitten by that still, ferocious cold. The Sabine River they found “on a high lonesome,” as the punchers say. They had to swim it. Wes revised his opinion of that runty black he rode. He had told Stokes furiously that he could own a dozen like the pony and still be afoot. But the little brute swam like an alligator-gar. They came out into the bitter January night, wet from the waist down, numbed and shivering. Two miles beyond the Sabine they made camp and slept until day.

On the second day of the trip they were ferried over the Trinity River and made camp on a dry ridge. Stokes went for corn-horse feed. The surly, bullying Smolly was left to guard the prisoner. Wes slipped behind his pony. It was now or never! He got his old Colt out.

“Stick ’em up, you dam’ mongrel!” he yelled. Smolly whirled with an oath. His hand slapped pistolbutt. That was suicide. The old Colt roared. Wes shot Smolly dead. He looked down grimly at him for a space, then resaddled the breed’s fine sorrel mare. He headed for his father’s house in Mount Calm.

There were to be several turning-points—points of hesitation, anyway—in the life of this preacher’s son who had been named for the great Methodist John Wesley. Wes Hardin—tales of his doings—Texas has talked over for nearly sixty years. Men yet alive (like Captain Jim Gillett, that old Ranger and splendid peace officer, Jeff Milton, Captain John R. Hughes, to name but three) knew him more or less intimately. I have listened to talk of him virtually all my life. He was the Individualist, born. What he wanted to do, he would do—and “God be on the side of the heaviest artillery!”

This was one of those crossroads in his life, this moment when a fine old frontier preacher sent his son running for Mexico. Texas, in the grip of carpet-baggers, of Davis’ scalawag State Police (largely negroes), was only the execution chamber for Wes Hardin.

Wes for once listened to his father. He left Mount Calm for San Antonio, on the first leg of his journey. But he ran head-on into three men of the State Police, between Belton and Waco. One travels that road, today, at 45 miles an hour, in a car. It was “horseback country” in ’71—and travelers made camp where they could. These three State Policemen, having captured Wes, made camp at nightfall. It seems more than passing strange, the way men treated the youngster!

They wanted him for murder—or for nothing. They had him. But no special precautions seem to have been taken against him. That boyish, handsome face must have fooled them, as it had fooled nine others. Too, they had been drinking. One Smith took the first watch while Jones and Davis slept. From his blanket, Wes watched calmly. He saw them take off their guns. He marked exactly where the guns were put. He listened to their snoring while he kept an eye on Smith.

The sentry’s head began to nod. Wes looked once more at the weapons, then settled like a panther on a limb, to wait for his moment. Smith began to breathe deeply. His head fell farther forward. Wes’ hands slid out. He got Davis’ shotgun, then Jones’ six-shooter.

He wasted no time on formalities. The average Texan of that day hated not even the carpetbagger as he hated one of Davis’ State Police (which were to be supplanted by the Texas Rangers as soon as Texas rid herself of Davis). Wes Hardin had seen too much bloodshed to be worried about killing enemies. This was the keynote, the explanation, of his whole career. It was the dominating impulse, that night, as he lifted himself with the shotgun, to aim at Smith.

He might have got out of that camp without firing a shot, but that would not have been like Wes Hardin. He killed Smith, then turned the second barrel upon Jones. Davis jumped up, yelling. Wes dropped the shotgun and snatched up Jones’ six-shooter. He slammed .45s at Davis until certain the policeman was dead.

Back, then, he turned to his father. He made an oath that never would he surrender, again, merely because the drop was on him. He kept that oath, too. It was one which was to add materially to the mortality-rate among those who came in contact with John Wesley Hardin. For he would take a chance at drawing and beating a shot from a gun pointed at him—a cocked gun. And to make his chance better, he practiced incessantly at the draw; he invented a “holster vest”—of which more later.

He got no nearer Mexico than Gonzales, where the Clements, his relatives, were gathering cattle for a drive up the trail. He went with them—with Manning, Gyp, Jim and Joe. He argued with a Mexican monte-dealer– and killed him, here. In February the trail-herd started for Kansas, moving up through Williamson County to cross Red River north of Montague County.

The Indians were levying a tax of ten cents a head on all cattle crossing The Nation. Wes was in charge of the herd and he conferred with other trail-bosses. It was decided to tell the feather-dusters where to go. This naturally caused trouble. One Indian had a bowstring to his ear, the arrow pointed at Wes, when he dropped with a bullet through his head.

The herd crossed into Kansas near Bluff Creek. Here the Osages bothered the herd, riding boldly into it to cut out fifteen or twenty head for the camp-kettles. One bunch of warriors loped into camp while Wes was out. They carried off everything that was not buried—including a fine silver-mounted bridle of the young trail-boss. They came raiding the herd again and this time Wes was very much present. He saw a big buck with his bridle. He told that buck to hand it over—and told all the Indians that no more cattle would be taken from this herd.

The buck from whom Wes had recovered his bridle showed fight. Wes hit him over the head with the barrel of his Colt. The other Osages were riding into the herd, beginning to cut out steers they fancied. Wes rammed in the hooks and shot the nearest one dead. The others hightailed. There was no more trouble on the trail until he got to Newton Prairie.

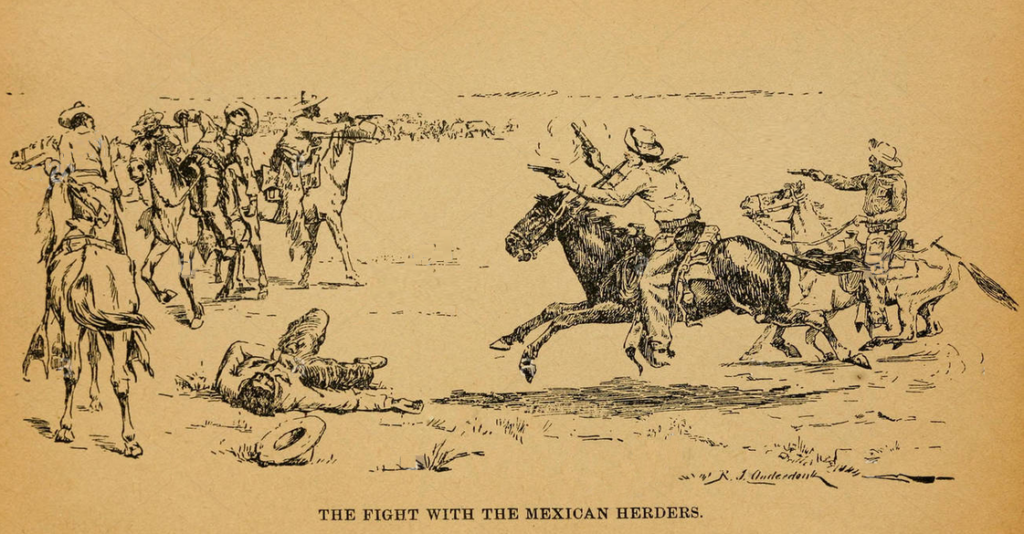

A Mexican trail-boss had a herd behind Wes. The Mex’ herd kept crowding and Wes’ remarks to the Mex’ boss were pointed. The Mex’ galloped back to his wagon, got a “sharp shooter” rifle and knelt on the ground. He took deliberate aim and the bullet grazed Wes’ hat. Something went wrong with the rifle, then. The Mex’ jerked his six-shooter and rode toward Wes, whose old cap-and-ball six-shooter had a rocking cylinder. By holding the cylinder, Wes managed to hit his opponent in the thigh. They came together later and in a horseback duel Wes killed the other. José was his name. The battle was general with the vaqueros. Wes dropped four.

On to Abilene! Abilene, surrounded this Spring of ’71 by seething masses of long-horned cattle; Abilene crowded by swaggering young men from the southern ranges, wide-hatted, bespurred and booted, the fringe of their leggings slapping as they rocked along the noisy length of Texas – “Hell” – Street; Abilene bossed by Wild Bill Hickok; Abilene the hell-roaring, twenty-four hours-a-day shipping-point for wild cattle, stopping point for wilder men.

And who—not excepting the famous Wild Bill—was wilder than this eighteen-year-old Texan who could handle the six-shooter as a stage-magician handles his “props!” Swaggering into the Alamo where Wild Bill hung out, he was quickly a marked man. The Clements brothers indicated him to drinkers with jerk of head or thumb. “Twenty men, that kid’s downed. Chain lightnin’ an’ eleven claps o’ thunder, with the six . Fight at the drop of a hat—an’ drop the hat hisself!'”

In Abilene, he met an older man—Texan, also whose name was to be bracketed with his own. But neither this devil-may-care youngster nor the grimmer, more calculating gambler thought of that. John Wesley Hardin and Ben Thompson—with Bill Longley they form a trio of killers whose names will always be associated with amazing gunplay.

Ben Thompson and a friend from Austin—Phil Coe—ran the Bull’s Head Saloon and gambling house on Texas Street. They had a picture of a bull painted on the false front of the building. The city council objected to the picture. The solemn members declared that the painter had too realistically, too minutely, detailed the bull’s anatomy. Wild Bill was deputed to order Thompson and Coe to either make the place the Steer Saloon or hide the bull behind a bush.

I have written elsewhere the story of Ben Thompson, drawing the man as Texas, in general, understands and recalls him. Nothing about him pointed to tendency to knuckle under to anybody on earth. He was finally persuaded to alter his sign. But he never forgave Wild Bill his part in the argument. When young Wes Hardin came toting twenty notches into Abilene, Thompson had an idea.

He told Wes that Wild Bill, a Northerner, always picked Southern men to kill. He suggested that Wes kill Hickok.

“I keep busy doing my own killings,” Wes told him. “If you want him killed, why don’t you do it yourself?”

“Oh, I’d rather get somebody else to do it,” Thompson said—doubtless with truth.

But Wes on his own account soon ran foul of Wild Bill. Hickok had a tremendous job on his hands, in Abilene. He has been variously described as a racketeering, cowardly, officer, and as a very paragon of chivalrous bravery. The truth, of course, lies between these two opinions. It seems certain that he was not a particularly good shot. But he was always ready to shoot, always looking for a suspicious move, and amazingly fast on the draw.

Such fire-eaters as Wes Hardin did nothing to make life easy for him. A kid will take a chance where a grown man hesitates. And a kid’s bullet is just as deadly as anyone’s. Hickok seems to have been rather friendly to Wes, who promptly swaggered the more. Wes’ accounts of making Wild Bill back water; of catching Wild Bill with the “road agents’ spin'” and disarming him—these, I think, have to be taken like the tails of the little birds in the proverb—with salt.

But Wes did clash with a bad man of not-too-heavy caliber. He killed the fellow rather easily. But Wild Bill, he thought, would now be on his trail. He jumped on his horse and rode furiously to Cottonwood. Here he stopped to think. Wild Bill, he knew, had Texas requisitions for him. Would the marshal decide to rid himself of Wes by ramming those requisitions down his famous Colt muzzles?

A Texas cowman got killed by a Mex’ named Bideno and temporarily solved the problem. Wes and some others chased Bideno down to Bluff. Wes killed him and rode triumphantly back to Abilene, hero of the cowboys who were friends of Bill Coran, the murdered cowman.

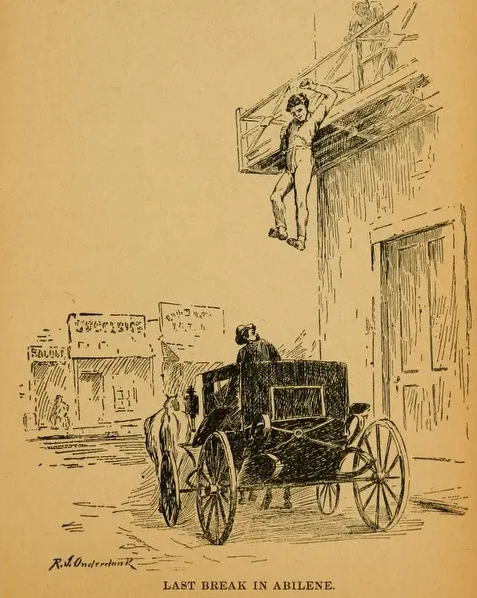

Wild Bill let him alone. But when on the night of July seventh, Wes waked to find a robber with a dirk bending over him, he first killed the fellow, then looked out the window. Wild Bill and four men came galloping up in a hack. They had heard the shooting. Wes looked at them as they jumped out. Three years, now, he had lived the life of the hunted lobo. He suspected everybody. At this moment, he particularly suspected Wild Bill. He believed that Hickok would kill him before yelling “hands up.” And here he stood with empty six-shooter.

The robber had run out into the hall to die—and he had carried Wes’ trousers with him. There was no time to recover them. Wes locked the room-door, then ran back to the window. The hack came under it, moving off from the rooming house door. Wes dropped lightly out upon its roof. He lay flat upon it. Presently, he dropped to the ground and went cautiously out of Abilene. He came to some farmer’s haystack beside the road. Into it he burrowed, watching that road.

A cowboy came along and Wes jumped out, waving his empty Colt menacingly. Down swung the cowboy from his saddle. From the direction of town came the sound of yelling, the thunder of pounding hoofs. Wes went into the saddle of the confiscated horse in a catlike jump.

“Give Wild Bill my love,” he told the cowboy. “My name is Wes Hardin. Wild Bill will recognize the name!”

And off he went. When the posse reached the cowboy their louder yells told Wes that the message had been delivered. He quirted the horse with rein-ends and grinned as he headed for Solomon River, three miles ahead. He kept in front and splashed across with a defiant yell. His herd-camp was just beyond. As he raced toward it, he looked back and saw three riders burning up the prairie. He quirted the “borrowed” horse a little harder. Into his camp he came and flung himself out of the saddle. Snatching up a Winchester that belonged to one of the Clements brothers, he went back to meet the three possemen.

“Get down, gentlemen!” he invited them. “Boot’s on the other hoof, now. No funny motions—no motions but what you have to make, taking off your clothes. You’re going back to Abilene the way you sent me out of it—without pants!”

And presently they marched off, afoot, pants-less and without boots. Wes Hardin watched them out of sight. Then he saddled up a horse, got a pair of pants and a six shooter and went back to Texas.

Gonzales County was the battleground of a war of factions—natural aftermath of reconstruction days. Surely, I have shown enough of the young bulldog, who had to red pepper his diet with excitement, to make it very plain that he could not remain in Gonzales where he had many relatives, without becoming a violent partizan. And to the natural violence of this internecine warfare was added the inflammatory bluster and swagger of negro State Police.

A couple of negro policemen decided to capture Wes. They found him in a grocery store with his back to the door. One covered him while the other waited outside. Wes held out his Colt with handle foremost—and with forefinger hooked in the trigger-guard…

The negro reached for it and the Colt did the “road agents’ spin” to come into Wes’ hand and explode. The negro fell with his own pistol still cocked in his hand. Wes jumped to the door and whanged away at the negro sitting a white mule outside. That one yelled and sent the mule at a 2.40 gait for the river-bottom.

His next encounter was with a posse of negroes. They had thought to surprise this young wolf. Instead, they were surprised. He killed three of them. Twenty-seven tallies….