Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Indian Fights and Fighters, by Cyrus Townsend Brady (published 1904)

I. The Original “Rough Riders”

No one will question the sweeping assertion that the grittiest band of American fighters that history tells us of was that which defended the Alamo. They surpassed by one Leonidas and his Spartans; for the Greeks had a messenger of defeat, the men of the Alamo had none. But close on the heels of the gallant Travis and his dauntless comrades came “Sandy” Forsyth’s original “Rough Riders,” who immortalized themselves by their terrific fight on Beecher’s Island on the Arickaree Fork of the Republican River, in Eastern Colorado, in the fall of 1868.

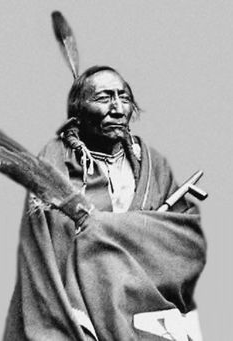

The contagion of the successful Indian attacks on Fort Phil Kearney had spread all over the Central West. The Kansas Pacific was then building to Denver, and its advance was furiously resisted by the Indians. As early as 1866, at a council held at Fort Ellsworth, Roman Nose, head chief of the Cheyennes, made a speech full of insolent defiance.

“This is the first time,” said the gigantic warrior, who was six feet three and magnificently proportioned,“that I have ever shaken the white man’s hand in friendship. If the railway is continued I shall be his enemy forever.”

There was no stopping the railway. Its progress was as irresistible as the movement of civilization itself. The Indians went on the war-path. The Cheyennes were led by their two principal chiefs, Black Kettle being the second. We shall see subsequently how Custer accounted for Black Kettle. This story deals with the adventures of Roman Nose.

As fighters these Indians are entitled to every admiration. As marauders they merit nothing but censure. The Indians of the early days of the nation, when Pennsylvania and New York were border states, and across the Alleghenies lay the frontier, were cruel enough, as the chronicle of the times abundantly testify; but they were angels of light compared with the Sioux and Cheyennes, the Kiowas, Arapahoes and Comanches, and these in turn were almost admirable beside the Apache. The first-named group were as cruel as they knew how to be, and they did not lack knowledge, either. The Apaches were more ingenious and devilish in their practices than the others. The Sioux and the Cheyennes were brutal with the brutality of a wild bull or a grizzly bear. To that same kind of brutality the Apaches added the malignity of a wildcat and the subtlety of a snake. The men of the first group would stand out and fight in the open to gain their ends, although they did not prefer to. They were soldiers and warriors as well as torturers. The Apache was a lurking skulker, but, when cornered, a magnificent fighter also. General Crook calls him “the tiger of the human species.” However, from the point of detestableness there wasn’t much to choose between them.

Perhaps we ought not to blame the Indians for acting just as our ancestors of, say the Stone Age, acted in all probability. And when you put modern weapons and modern whisky in the hands of the Stone Age men you need not be surprised at the consequences. The Indian question is a terrible one any way you take it. It cannot be denied they have been treated abominably by the United States, and that they have good cause for resentment; but the situation has been so peculiar that strife has been inevitable.

As patriots defending their country, they are not without certain definite claims to our respect. Recognizing the right of the aborigines to the soil, the government has yet arbitrarily abrogated that right at pleasure. At times the Indians have been regarded as independent nations, with which all differences were to be settled by treaty as between equals; and again, as a body of subjects whose affairs could be and would be administered willy-nilly by the United States. Such vacillations are certain to result in trouble, especially as, needless to say, the Indians invariably considered themselves as much independent nations as England and France might consider themselves, in dealing with the United States or with one another. And the Indians naturally claimed and insisted that the territory where their fathers had roamed for centuries belonged solely and wholly to them. They admitted no suzerainty of any sort, either. And they held the petty force the government put in the field in supreme contempt until they learned by bitter experience the illimitable power of the United States.

To settle such a growing question in a word, offhand, as it were, is, of course, impossible, nor does the settlement lie within the province of these articles; but it may be said that if the United States had definitely decided upon one policy or the other, and had then concentrated all its strength upon the problem; if it had realized the character of the people with whom it was dealing, and had made such display of its force as would have rendered it apparent, to the keenest as well as to the most stupid and besotted of the Indians, that resistance was entirely futile, things might have been different. But it is the solemn truth that never, in any of the Indian wars west of the Missouri, has there been a force of soldiers in the field adequate to deal with the question. The blood of thousands of soldiers and settlers—men, women, and children—might have been spared had this fact been realized and acted upon.

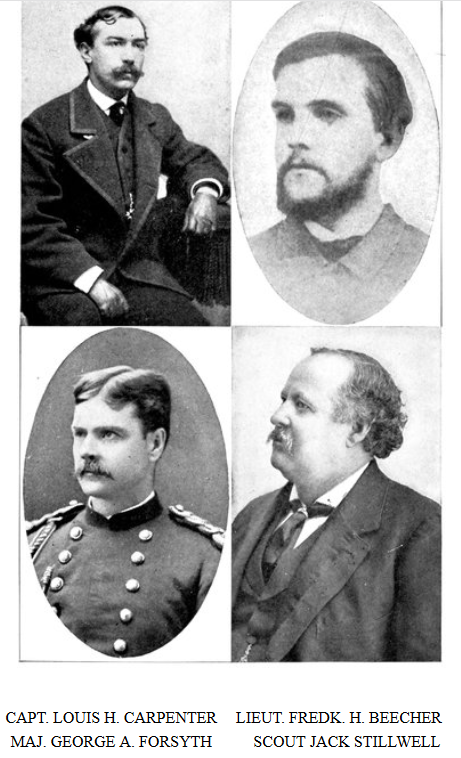

The Cheyennes swept through western Kansas like a devastating storm. In one month they cut off, killed, or captured eighty-four different settlers, including their wives and children. They swept the country bare. Again and again the different gangs of builders were wiped out, but the railroad went on. General Sheridan finally took the field in person, as usual with an inadequate force at his disposal. One of his aides-de-camp was a young cavalry officer named George Alexander Forsyth, commonly known to his friends as “Sandy” Forsyth. He had entered the volunteer army in 1861 as a private of dragoons in a Chicago company. A mere boy, he had come out a brigadier-general. In the permanent establishment he was a major in the Ninth Cavalry. Sheridan knew him. He was one of the two officers who made that magnificent ride with the great commander that saved the day at Winchester, and it was due to his suggestion that Sheridan rode down the readjusted lines before they made the return advance which decided the fate of the battle. During all that mad gallop and hard fighting young Forsyth rode with the General. Today he is the only survivor of that ride.

Forsyth was a fighter all through, and he wanted to get into the field in command of some of the troops operating directly on the Indians in the campaign under consideration. No officer was willing to surrender his command to Forsyth on the eve of active operations, and there was no way, apparently, by which he could do anything until Sheridan acceded to his importunities by authorizing him to raise a company of scouts for the campaign. He was directed, if he could do so, to enlist fifty men, who, as there was no provision for the employment of scouts or civilian auxiliaries, were of necessity carried on the payrolls as quartermasters’ employees for the magnificent sum of one dollar per day. They were to provide their own horses, but were allowed thirty cents a day for the use of them, and the horses were to be paid for by the government if they were “expended” during the campaign. They were equipped with saddle, bridle, haversack, canteen, blanket, knife, tin cup, Spencer repeating rifle, good for seven shots without reloading, six in the magazine, one in the barrel, and a heavy Colt’s army revolver. There were no tents or other similar conveniences, and four mules constituted the baggage train. The force was intended to be strictly mobile, and it was. Each man carried on his person one hundred and forty rounds of ammunition for his rifle and thirty rounds for his revolver. The four mules carried the medical supplies and four thousand rounds of extra ammunition. Each officer and man took seven days’ rations. What he could not carry on his person was loaded on the pack mules; scanty rations they were, too.

As soon as it was known that the troop was to be organized, Forsyth was overwhelmed with applications from men who wished to join it. He had the pick of the frontier to select from. He chose thirty men at Fort Harker and the remaining twenty from Fort Hayes. Undoubtedly they were the best men in the West for the purpose. To assist him, Lieutenant Frederick H. Beecher, of the Third Infantry, was detailed as second in command. Beecher was a young officer with a record. He had displayed peculiar heroism at the great battle of Gettysburg, where he had been so badly wounded that he was lame for the balance of his life. He was a nephew of the great Henry Ward Beecher and a worthy representative of the distinguished family whose name he bore. The surgeon of the party was Dr. John H. Mooers, a highly-trained physician, who had come to the West in a spirit of restless adventure. He had settled at Hayes City and was familiar with the frontier. The guide of the party was Sharp Grover, one of the remarkable plainsmen of the time, regarded as the best scout in the government service. The first-sergeant was W. H. H. McCall, formerly brigadier-general, United States Volunteers. McCall, in command of a Pennsylvania regiment, had been promoted for conspicuous gallantry on the field, when John B. Gordon made his magnificent dash out of Petersburg and attacked Fort Steadman.

The personnel of the troop was about equally divided between hunters and trappers and veterans of the Civil War, nearly all of whom had held commissions in either the Union or Confederate Army, for the command included men from both sides of Mason and Dixon’s line. It was a hard-bitten, unruly group of fighters. Forsyth was just the man for them. While he did not attempt to enforce the discipline of the Regular Army, he kept them regularly in hand. He took just five days to get his men and start on the march. They left Fort Wallace, the temporary terminus of the Kansas Pacific Railroad, in response to a telegram from Sheridan that the Indians were in force in the vicinity, and scouted the country for some six days, finally striking the Indian trail, which grew larger and better defined as they pursued it. Although it was evident that the Indians they were chasing greatly outnumbered them, they had come out for a fight and wanted one, so they pressed on. They got one, too.

II. The Island of Death

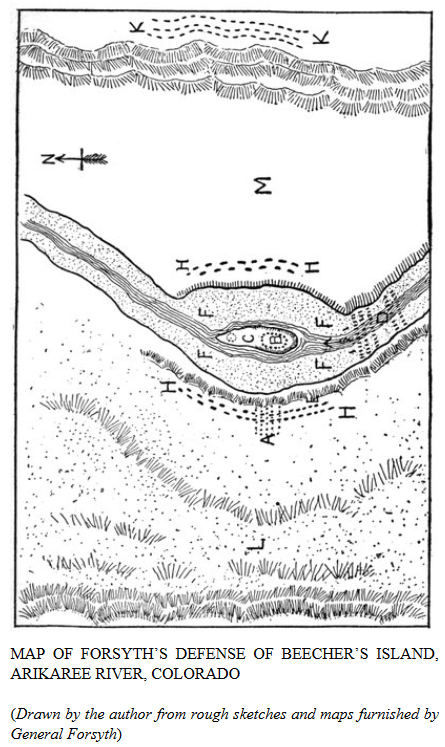

On the evening of the fifteenth of September, hot on the trail, now like a well-beaten road, they rode through a depression or a ravine, which gave entrance into a valley some two miles wide and about the same length. Through this valley ran a little river, the Arickaree. They encamped on the south bank of the river about four o’clock in the afternoon. The horses and men were weary with hard riding. Grazing was good. They were within striking distance of the Indians now. Forsyth believed there were too many of them to run away from such a small body as his troop of scouts. He was right. The Indians had retreated as far as they intended to.

The river bed, which was bordered by wild plums, willows and alders, ran through the middle of the valley. The bed of the river was about one hundred and forty yards wide. In the middle of it was an island about twenty yards wide and sixty yards long. The gravelly upper end of the island, which rose about two feet above the water level, was covered with a thick growth of stunted bushes, principally alders and willows; at the lower end, which sloped to the water’s edge, there rose a solitary cottonwood tree. There had been little rain for some time, and this river bed for the greater part of its width was dry and hard. For a space of four or five yards on either side of the island there was water, not over a foot deep, languidly washing the gravelled shores. When the river bed was full the island probably was overflowed. Such islands form from time to time, and are washed away as quickly as they develop. The banks of the river bed on either side commanded the island.

The simple preparations for the camp of that body of men were soon made. As night fell they rolled themselves in their blankets, with the exception of the sentries, and went to sleep with the careless indifference of veterans under such circumstances.

Forsyth, however, as became a captain, was not so careless or so reckless as his men. They were alone in the heart of the Indian country, in close proximity to an overwhelming force, and liable to attack at any moment. He knew that their movements had been observed by the Indians during the past few days. Therefore the young commander was on the alert throughout the night, visiting the outposts from time to time to see that careful watch was kept.

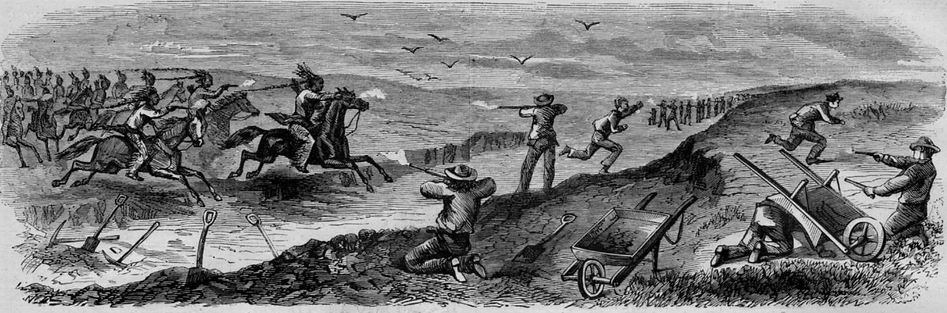

Just as the first streaks of dawn began to “lace the severing clouds,” he happened to be standing by the sentry farthest from the camp. Silhouetted against the sky-line they saw the feathered head of an Indian. For Forsyth to fire at him was the work of an instant. At the same time a party which had crept nearer to the picket line unobserved dashed boldly at the horses, and resorting to the usual devices with bells, horns, hideous yells, and waving buffalo robes, attempted to stampede the herd.

Men like those scouts under such circumstances slept with their boots on. The first shot called them into instant action. They ran instinctively to the picket line. A sharp fire, and the Indians were driven off at once. Only the pack mules got away. No pursuit was attempted, of course. Orders were given for the men to saddle their horses and stand by them. In a few moments the command was drawn up in line, each man standing by his horse’s head, bridle reins through his left arm, his rifle grasped in his right hand—ready! Scarcely had the company been thus assembled when Grover caught Forsyth’s arm and pointed down the valley.

“My God!” he cried, “look at the Injuns!”

In front of them, on the right of them, in the rear of them, the hills and valleys on both sides of the river seemed suddenly to be alive with Indians. It was as quick a transformation from a scene of peaceful quiet to a valley filled with an armed force as the whistle of Roderick Dhu had effected in the Scottish glen.

The way to the left, by which they had entered the valley, was still open. Forsyth could have made a running fight for it and dashed for the gorge through which he had entered the valley. There were, apparently, no Indians barring the way in that direction. But Forsyth realized instantly that for him to retreat would mean the destruction of his command, that the Indians had in all probability purposely left him that way of escape, and if he tried it he would be ambushed in the defile and slain. That was just what they wanted him to do, it was evident. That was why he did not attempt it. He was cornered, but he was not beaten, and he did not think he could be. Besides, he had come for that fight, and that fight he was bound to have.

Whatever he was to do he must do quickly. There was no place to which he could go save the island. That was not much of a place at best, but it was the one strategic point presented by the situation. Pouring a heavy fire into the Indians, Forsyth directed his men to take possession of the island under cover of the smoke. In the movement everything had to be abandoned, including the medical stores and rations, but the precious ammunition—that must be secured at all hazards. Protected by a squad of expert riflemen on the river bank, who presently joined them, the scouts reached the island in safety, tied their horses to the bushes around the edge of it, and in the intervals of fighting set to work digging rifle-pits covering an ellipse twenty by forty yards, one pit for each man, with which to defend the upper and higher part of the island They had nothing to dig with except tin cups, tin plates, and their bowie knives, but they dug like men. There was no lingering or hesitation about it.

The chief of the Indian force, which was made up of Northern Cheyennes, Oglala and Brulé Sioux, with a few Arapahoes and a number of Dog Soldiers, was the famous Roman Nose, an enemy to be feared indeed. He was filled with disgust and indignation at the failure of his men to occupy the island, the strategic importance of which he at once detected. It is believed that orders to seize the island had been given, but for some reason they had not been obeyed; and to this oversight or failure was due the ultimate safety of Forsyth’s men. It was not safe to neglect the smallest point in fighting with a soldier like Forsyth.

With more military skill than they had ever displayed before, the Indians deliberately made preparations for battle. The force at the disposal of Roman Nose was something less than one thousand warriors. They were accompanied by their squaws and children. The latter took position on the bluffs on the east bank of the river, just out of range, where they could see the whole affair. Like the ladies of the ancient tournaments, they were eager to witness the fighting and welcome the victors, who, for they never doubted the outcome, were certain to be their own.

Roman Nose next lined the banks of the river on both sides with dismounted riflemen, skillfully using such concealment as the ground afforded. The banks were slightly higher than the island, and the Indians had a plunging fire upon the little party. The riflemen on the banks opened fire at once. A storm of bullets was poured upon the devoted band on the island. The scouts, husbanding their ammunition, slowly and deliberately replied, endeavoring, with signal success, to make every shot tell. As one man said, they reckoned “every ca’tridge was wuth at least one Injun.” The horses of the troop, having no protection, received the brunt of the first fire. They fell rapidly, and their carcasses rising in front of the rifle-pits afforded added protection to the soldiers. There must have been a renegade white man among the savages, for in a lull of the firing the men on the island heard a voice announce in perfect English, “There goes the last of their horses, anyway.” Besides this, from time to time, the notes of an artillery bugle were heard from the shore. The casualties had not been serious while the horses stood, but as soon as they were all down the men began to suffer.

During this time Forsyth had been walking about in the little circle of defenders encouraging his men. He was met on all sides with insistent demands that he lie down and take cover, and, the firing becoming hotter, he at last complied. The rifle-pit which Surgeon Mooers had made was a little wider than that of the other men, and as it was a good place from which to direct the fighting, at the doctor’s suggestion some of the scouts scooped it out to make it a little larger, and Forsyth lay down by him.

The fire of the Indians had been increasing. Several scouts were killed, more mortally wounded, and some slightly wounded. Doctor Mooers was hit in the forehead and mortally wounded. He lingered for three days, saying but one intelligent word during the whole period. Although he was blind and speechless, his motions sometimes 85indicated that he knew where he was. He would frequently reach out his foot and touch Forsyth. A bullet struck Forsyth in the right thigh, and glancing upwards bedded itself in the flesh, causing excruciating pain. He suffered exquisite anguish, but his present sufferings were just beginning, for a second bullet struck him in the leg, between the knee and ankle, and smashed the bone, and a third glanced across his forehead, slightly fracturing his skull and giving him a splitting headache, although he had no time to attend to it then.

III. The Charge of the Five Hundred

During all this time Roman Nose and his horsemen had withdrawn around the bend up the river, which screened them from the island. At this juncture they appeared in full force, trotting up the bed of the river in open order in eight ranks of about sixty front. Ahead of them, on a magnificent chestnut horse, trotted Roman Nose. The warriors were hideously painted, and all were naked except for moccasins and cartridge belts. Eagle feathers were stuck in their long hair, and many of them wore gorgeous feather war bonnets. They sat their horses without saddles or stirrups, some of them having lariats twisted around the horses’ bellies like a surcingle. Roman Nose wore a magnificent war bonnet of feathers streaming behind him in the wind and surmounted by two buffalo-horns; around his waist he had tied an officer’s brilliant scarlet silk sash, which had been presented to him at the Fort Ellsworth conference. The sunlight illumined the bronze body of the savage Hercules, exhibiting the magnificent proportions of the man. Those who followed him were in every way worthy of their leader.

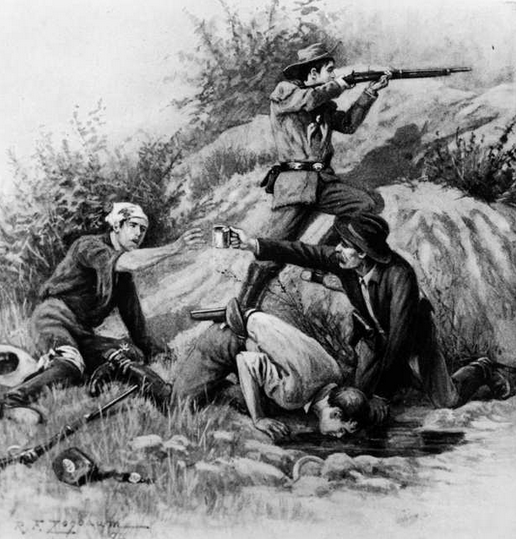

As the Indian cavalry appeared around the bend to the music of that bugle, the fire upon the island from the banks redoubled in intensity. Forsyth instantly divined that Roman Nose was about to attempt to ride him down. He also realized that, so soon as the horses were upon him, the rifle fire from the bank would of necessity be stopped. His order to his men was to cease firing, therefore; to load the magazines of their rifles, charge their revolvers, and wait until he gave the order to fire. The rifles of the dead and those of the party too severely wounded to use them were distributed among those scouts yet unharmed. Some of the wounded insisted upon fighting. Forsyth propped himself up in his rifle-pit, his back and shoulders resting against the pile of earth, his rifle and revolver in hand. He could see his own men, and also the Indians coming up the river.

Presently, shouting their war songs, at a wild pealed whoop from their chief, the Indian horsemen broke into a gallop, Roman Nose leading the advance, shaking his heavy Spencer rifle—captured, possibly, from Fetterman’s men—in the air as if it had been a reed. There was a last burst of rifle fire from the banks, and the rattle of musketry was displaced by the war songs of the Indians and the yells of the squaws and children on the slopes of the hills. As the smoke drifted away on that sunny September morning, they saw the Indians almost upon them. In spite of his terrible wounds the heroic Forsyth was thoroughly in command. Waiting until the tactical moment when the Indians were but fifty yards away and coming at a terrific speed, he raised himself on his hands to a sitting position and cried, “Now!”

The men rose to their knees, brought their guns to their shoulders, and poured a volley right into the face of the furious advance. An instant later, with another cartridge in the barrel they delivered a second volley. Horses and men went down in every direction; but, like the magnificent warriors they were, the Indians closed up and came sweeping down. The third volley was poured into them. Still they came. The war songs had ceased by this time, but in undaunted spirit, still pealing his war cry above the crashing of the bullets, at the head of his band, with his magnificent determination unshaken, Roman Nose led such a ride as no Indian ever attempted before or since. And still those quiet, cool men continued to pump bullets into the horde. At the fourth volley the medicine man on the left of the line and the second in command went down. The Indians hesitated at this reverse, but swinging his rifle high in the air in battle frenzy, the great war chief rallied them, and they once more advanced. The fifth volley staggered them still more. Great gaps were opened in their ranks. Horses and men fell dead, but the impetus was so great, and the courage and example of their leader so splendid, that the survivors came on unchecked. The sixth volley did the work. Just as he was about to leap on the island, Roman Nose and his horse were both shot to pieces. The force of the charge, however, was so great that the line was not yet entirely broken. The horsemen were within a few feet of the scouts, when the seventh volley was poured into their very faces. As a gigantic wave meets a sharply jutting rock and is parted, falling harmlessly on either side of it, so was that charge divided, the Indians swinging themselves to the sides of their horses as they swept down the length of the island.

The scouts sprang to their feet at this juncture, and almost at contact range jammed their revolver shots at the disorganized masses. The Indians fled precipitately to the banks on either side, and the yelling of the war chants of the squaws and children changed into wails of anguish and despair, as they marked the death of Roman Nose and the horrible slaughter of his followers.

It was a most magnificent charge, and one which for splendid daring and reckless heroism would have done credit to the best troops of any nation in the world. And magnificently had it been met. Powell’s defense of the corral on Piney Island was a remarkable achievement, but it was not to be compared to the fighting of these scouts on the little open, unprotected heap of sand and gravel in the Arickaree.

As soon as the Indian horsemen withdrew, baffled and furious, a rifle fire opened once more from the banks. Lieutenant Beecher, who had heroically performed his part in the defense, crawled over to Forsyth and said:

“I have my death wound, General. I am shot in the side and dying.”

He said the words quietly and simply, as if his communication was utterly commonplace, then stretched himself out by his wounded commander, lying, like Steerforth, with his face upon his arm.

“No, Beecher, no,” said Forsyth, out of his own anguish; “it cannot be as bad as that.”

“Yes,” said the young officer, “good-night.”

There was nothing to be done for him. Forsyth heard him whisper a word or two of his mother, and then delirium supervened. By evening he was dead. In memory of the brave young officer, they called the place where he had died Beecher’s Island.

At two o’clock in the afternoon a second charge of horse was assayed in much the same way as the first had been delivered; but there was no longer a great war chief in command, and this time the Indians broke at one hundred yards from the island. At six o’clock at night they made a final attempt. The whole party, horse and foot, in a solid mass rushed from all sides upon the island. They came forward, yelling and firing, but they were met with so severe a fire from the rifle-pits that, although some of them actually reached the foot of the island, they could not maintain their position, and were driven back with frightful loss. The men on the island deliberately picked off Indian after Indian as they came, so that the dry river bed ran with blood. The place was a very hell to the Indians. They withdrew at last, baffled, crushed, beaten.

With nightfall the men on the island could take account of the situation. Two officers and four men were dead or dying, one officer and eight men were so severely wounded that their condition was critical. Eight men were less severely wounded, making twenty-three casualties out of fifty-one officers and men. There were no rations, but thank God there was an abundance of water. They could get it easily by digging in the sandy surface of the island. They could subsist, if necessary, on strips of meat cut from the bodies of the horses. The most serious lack was of medical attention. The doctor lying unconscious, the wounded were forced to get along with the unskilled care of their comrades, and with water, and rags torn from clothing for dressings. Little could be done for them. The day had been frightfully hot, but, fortunately, a heavy rain fell in the night, which somewhat refreshed them. The rifle-pits were deepened and made continuous by piling saddles and equipments, and by further digging in the interspaces.

One of the curious Indian superstitions, which has often served the white man against whom he has fought to good purpose, is that when a man is killed in the dark he must pass all eternity in darkness. Consequently, he rarely ever attacks at night. Forsyth’s party felt reasonably secure from any further attack, therefore, notwithstanding which they kept watch.

IV. The Siege of the Island

As soon as darkness settled down volunteers were called for to carry the news of their predicament to Fort Wallace, one hundred miles away. Every man able to travel offered himself for the perilous journey. Forsyth selected Trudeau and Stillwell. Trudeau was a veteran hunter, Stillwell a youngster only nineteen years of age, although he already gave promise of the fame as a scout which he afterwards acquired. To them he gave the only map he possessed. They were to ask the commander of Fort Wallace to come to his assistance. As soon as the two brave scouts had left, every one realized that a long wait would be entailed upon the little band, if, indeed, it was not overwhelmed meanwhile, before any relieving force could reach the island. And there were grave doubts as to whether, in any event, Trudeau and Stillwell could get through the Indians. It was not a pleasant night they spent, therefore, although they were busy strengthening the defenses, and nobody got any sleep.

Early the next morning the Indians again made their appearance. They had hoped that Forsyth and his men would have endeavored to retreat during the night, in which event they would have followed the trail and speedily annihilated the whole command. But Forsyth was too good a soldier to leave the position he had chosen. During the fighting of the day before he had asked Grover his opinion as to whether the Indians could deliver any more formidable attack than the one which had resulted in the death of Roman Nose, and Grover, who had had large experience, assured him that they had done the best they could, and indeed better than he or any other scout had ever seen or heard of in any Indian warfare. Forsyth was satisfied, therefore, that they could maintain the position, at least until they starved.

The Indians were quickly apprised, by a volley which killed at least one man, that the defenders of the island were still there. The place was closely invested, and although the Indians made several attempts to approach it under a white flag, they were forced back by the accurate fire of the scouts, and compelled to keep their distance. It was very hot. The sufferings of the wounded were something frightful. The Indians were having troubles of their own, too. All night and all day the defenders could hear the beating of the tom-toms or drums and the mournful death songs and wails of the women over the bodies of the slain, all but three of whom had been removed during the night. These three were lying so near the rifle-pits that the Indians did not dare to approach near enough to get them. The three dead men had actually gained the shore of the island before they had been killed.

The command on the island had plenty to eat, such as it was. There was horse and mule meat in abundance. They ate it raw, when they got hungry enough. Water was plentiful. All they had to do was to dig the rifle-pits a little deeper, and it came forth in great quantities. It was weary waiting, but there was nothing else to do. They dared not relax their vigilance a moment. The next night, the second, Forsyth despatched two more scouts, fearing the first two might not have got through, thus seeking to “make assurance double sure.” This pair was not so successful as the first. They came back about three o’clock in the morning, having been unable to pass the Indians, for every outlet was heavily guarded.

The third day the Indian women and children were observed withdrawing from the vicinity. This cheered the men greatly, as it was a sign that the Indians intended to abandon the siege. The warriors still remained, however, and any incautious exposure was a signal for a volley. That night two more men were dispatched with an urgent appeal, and these two succeeded in getting through. They bore this message:

Sept. 19, 1868.

To Colonel Bankhead, or Commanding Officer,

Fort Wallace:

I sent you two messengers on the night of the 17th inst., informing you of my critical condition. I tried to send two more last night, but they did not succeed in passing the Indian pickets, and returned. If the others have not arrived, then hasten at once to my assistance. I have eight badly wounded and ten slightly wounded men to take in…. Lieutenant Beecher is dead, and Acting Assistant Surgeon Mooers probably cannot live the night out. He was hit in the head Thursday, and has spoken but one rational word since. I am wounded in two places—in the right thigh, and my left leg is broken below the knee….

I am on a little island, and have still plenty of ammunition left. We are living on mule and horse meat, and are entirely out of rations. If it was not for so many wounded, I would come in, and take the chances of whipping them if attacked. They are evidently sick of their bargain…. I can hold out for six days longer if absolutely necessary, but please lose no time.

P.S.—My surgeon having been mortally wounded, none of my wounded have had their wounds dressed yet, so please bring out a surgeon with you.

The fourth day passed like the preceding, the squaws all gone, the Indians still watchful. The wound in Forsyth’s leg had become excruciatingly painful, and he begged some of the men to cut out the bullet. But they discovered that it had lodged near the femoral artery, and fearful lest they should cut the artery and the young commander should bleed to death, they positively refused. In desperation, Forsyth cut it out himself. He had his razor in his saddle bags and, while two men pressed the flesh back, he performed the operation successfully, to his immediate relief.

The fifth day the mule and horse meat became putrid and therefore unfit to eat. An unlucky coyote wandered over to the island, however, and one of the men was fortunate enough to shoot him. Small though he was, he was a welcome addition to their larder, for he was fresh. There was but little skirmishing on the fifth day, and the place appeared to be deserted. Forsyth had half a dozen of his men raise him on a blanket above the level of the rifle beds so that he might survey the scene himself. Not all the Indians were gone, for a sudden fusillade burst out from the bank. One of the men let go the corner of the blanket which he held while the others were easing Forsyth down, and he fell upon his wounded leg with so much force that the bone protruded through the flesh. He records that he used some severe language to that scout.

On the sixth day Forsyth assembled his men about him, and told them that those who were well enough to leave the island would better do so and make for Fort Wallace; that it was more than possible that none of the messengers had succeeded in getting through; that the men had stood by him heroically, and that they would all starve to death where they were unless relief should come; and that they were entitled to a chance for their lives. He believed the Indians, who had at last disappeared, had received such a severe lesson that they would not attack again, and that if the men were circumspect they could get through to Fort Wallace in safety. The wounded, including himself, must be left to take care of themselves and take the chances of escape from the island.

The proposition was received in surprised silence for a few moments, and then there was a simultaneous shout of refusal from every man: “Never! We’ll stand by you.” McCall, the first sergeant and Forsyth’s right-hand man since Beecher had been killed, shouted out emphatically: “We’ve fought together, and, by Heaven, if need be, we’ll die together.”

They could not carry the wounded; they would not abandon them. Remember these men were not regular soldiers. They were simply a company of scouts, more or less loosely bound together, but, as McCall had pointed out, they were tied to one another by something stronger than discipline. Not a man left the island, although it would have been easy for the unwounded to do so, and possibly they might have escaped in safety.

For two more days they stood it out. There was no fighting during this time, but the presence of an Indian vedette indicated that they were under observation. They gathered some wild plums and made some jelly for the wounded; but no game came their way, and there was little for them to do but draw in their belts a little tighter and go hungry, or, better, go hungrier. On the morning of the ninth day, one of the men on watch suddenly sprang to his feet, shouting:

“There are moving men on the hills.” Everybody who could stand was up in an instant, and Grover, the keen-eyed scout, shouted triumphantly:

“By the God above us, there’s an ambulance!” They were rescued at last.

5