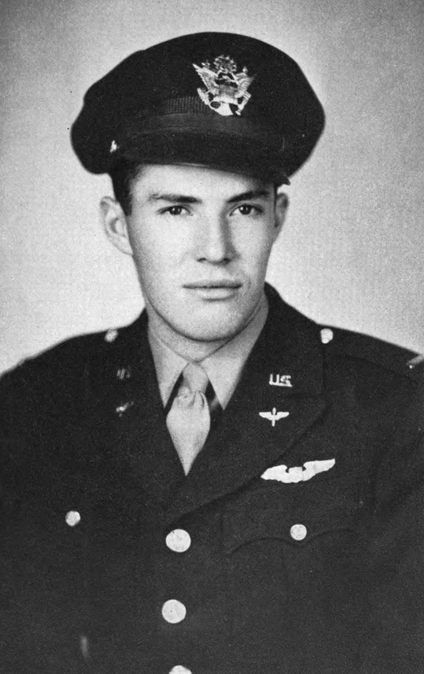

Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Serenade to the Big Bird, by Bert Stiles (published 1952). Assigned as a co-pilot to the 401st Bomb Squadron, 91st Bomb Group at Bassingbourn, England, Stiles flew his first combat mission on April 19, 1944.

We went on our first one on the nineteenth of April. We had a practice mission the afternoon before, the first time we’d flown in a month, and we weren’t bad, so the colonel said we could go.

Some major gave us a little talk about how we might as well start sometime, and were there any questions, and just fly that baby in close and you’ll come home every time.

The squadron was short on crews or we would have had some more practice missions.

After the major let us go, Sam got the crew over in the corner and told us we’d have to be on the ball from here on in.

“And you’ve got to fly in close,” he told me. “I’m not going to do all the work.”

He had slept most of the way across the Atlantic, but now he was feeling serious.

I’d only flown formation in a 17 twice, once in the phases and once on the practice mission. I wasn’t very hot.

“This is the big league now,” Sam said.

Everybody said so. We’d been in the Bomb Group for four days and everyone in the Group knew he was in the big league.

After Sam let the crew go I asked him, “Are you scared?”

“I’m Sam,” he said.

He was all right. He was ready to go.

We went over to the club then. It didn’t seem any different. Nobody seemed to care that there was an alert on, and a raid tomorrow. Nobody went off in the corner to brood.

We had pork chops for dinner, and I sat next to a guy in our squadron named La something. I called him La French, because I could never remember the last part. He was big and acted half-drunk most of the time and he looked like a pirate.

“So you’ve joined our noble band,” he said. “We’ll probably go tomorrow,” I said.

“A joy ride,” he said. “Lucky boy!”

“Where to?”

“What does it matter?” He waved his hands. “The Luftwaffe is beat. Haven’t you heard?”

That was fine with me. I wanted to see a Focke-Wulf some time, but I didn’t care about seeing one tomorrow.

After chow La French and I went out to say good night to his airplane. The dispersal area is way down past the skeet range and a turnip field. We took our bikes and rode through a world of blue and green and soft through the haze.

We saw that the plane was chocked in good for the night, and then hung around waiting for the sun to go down.

“Sort of pretty,” La French said.

I thought he was talking to himself, so I didn’t say anything.

I was well established in the sack when a bunch of guys came into the room and turned the lights on. A bombardier and a navigator were putting their co-pilot to bed, but he’d broken away into my room.

He was pretty drunk, and he really had the bright stare of death in his eyes.

“So you made the team?” this co-pilot said.

I said, “I guess so.” I was about half-asleep.

All he did was laugh, just stand there and laugh, until the whole room was full of it, and shaking from it.

The bombardier and navigator got him under control then and took him away to bed. The bombardier came back after they put him away.

“That baby’s got it bad,” he said. “He won’t last much longer. He’s seen too many guys go down.”

When the lights were out again I lay there for a while, not ready to go to sleep.

I wasn’t scared. I was just wondering what I was doing here at all. I’d been building up to that night for a long time. I used to dream about it at school, sitting there drinking cokes with some girl, reading the airplane magazines. I used to think about it all the time in the cadets. And now we were really here, ready to go to war in the morning. We were going out to knock off the Germans.

I knew right then that I didn’t know much about killing.

I didn’t feel like the Polish Spitfire pilots we met in Iceland, coming over. They had it bad. They wanted to kill every German in the world. But it was different with me, I’d never been shot at, or bombed. My folks live on York Street in Denver, which is a long way from this war.

All I knew about war I got through books and movies and magazine articles, and listening to a few big wheels who came through the cadet schools to give us the low-down. It wasn’t in my blood, it was all in my mind.

The whole idea was to blow up just as much Germany tomorrow as possible. From way up high, it wouldn’t mean a thing to me. I wouldn’t know if any women or little kids got in the way. I’d thought about it before, but that night it was close. The more I thought of it, the uglier it seemed.

What I wanted to do tomorrow was ski down Baldy up at Sun Valley, or wade out into the surf at Santa Monica, and get all knocked out in the waves, and come in and lie in the sun all afternoon.

Instead I was going on a trip, a long trip, to help some other guys beat up a town, or an oil plant, or a steel mill. It seemed like a pretty futile way to live.

Then I thought a while about the eight guys who had slept in my bed in the last four months. They were all dead or down in some German Stalag, or getting drunk in Sweden, or hiding in a French ditch somewhere. They hadn’t hurt the bed much. It was a nice sack, the only good one in England up to then.

Some joker dragged me out of it at two in the morning.

“Come on,” he said, “breakfast at two thirty, briefing at three thirty.” It was Lieutenant Porada.

Somebody upstairs who wasn’t on the list was shouting, “Drag the Luftwaffe up and give ’em a blow for me.”

I walked over to the mess hall through the dark. The stars were out and it was pretty cold.

Before missions we used to eat at the big dogs’ mess hall, Number 1, with the colonels and the majors, and the ground- grippers like weathermen and intelligence. I was the first one in there, and I had to eat eggs and toast for a whole hour before we went to briefing.

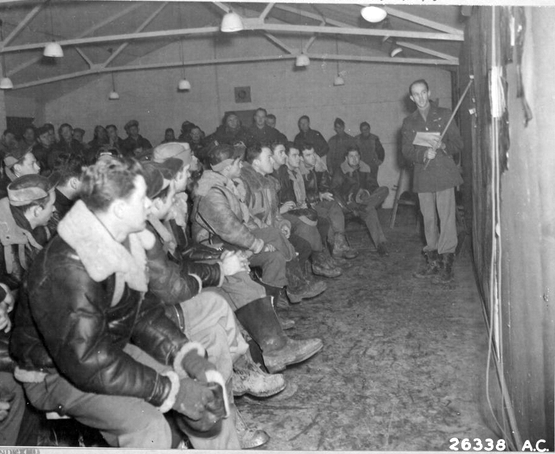

The briefing was in a big overgrown Nissen hut. Some major got up first and told us we were going down south to Kassel to a place called Eschwege, where the Germans had a fighter park, a sort of shipping point and comfort station for ships clearing to the forward bases. They showed us where it was on the big wall map, and how it looked to the recco cameras the last time they were over there. The weatherman showed us where the clouds would be, and the guy in charge of traffic told us how to taxi out.

The formation was all drawn up on the blackboard and I copied down all the ship numbers and where they flew. We were flying right wing off the lead ship of the high squadron.

The navigators went somewhere else for some more briefing. Sam went off to change his pants, and I queued up in the co-pilots’ line for kits. The gunners were somewhere else getting the same thing. There wasn’t room for them in our briefing hut.

Standing there in line, I could tell this was going to be the bad time. We were supposed to have a record escort, 47’s and 51’s all over, all the way. But we were going in deep, and the Germans didn’t want us over there at all.

The equipment hut was a mess with everyone trying to dress in the same place at the same time. I decided to wear an electric suit because I hate long-johns. I put on my O.D.’s over that, and a summer flying suit over that, and a leather jacket on top. A Mae West comes last.

I was sweating before I got into all my clothes, and by the time I had heaved my flak suit and parachute on the track I could feel the sweat rolling down my knees and pooling up in my insteps.

The rest of the crew was still struggling in the equipment room, so Crone and I lay down among the parachutes and looked at the stars. It was time to think again.

I said hello to Lady Luck up there somewhere in the blue. As long as she went along too I knew I’d be all right. I told her where we were going, but I think she knew already.

The others came out in time and the truck took us out to the plane. Everybody was talking fast and laughing, and I felt sort of ready, like I’d been waiting for a long time for this to happen.

Lewis was trying to put his guns in the turret, while I tried to stow my flak suit under the seat where I could reach for it fast.

“Goddamn it,” I said, “there ought to be more room in these goddamned things.”

“Take it easy,” he said.

I couldn’t find my helmet, and one of my gloves was missing. Bird and Benson were all tangled up in the nose getting their guns in. Sam was the only smart one. He stayed outside talking to the crew chief until everyone else got set.

We were flying somebody else’s plane, the Keystone Mama. I turned my flashlight on the brown lady with no brassiere, painted on the side, and decided they were short of artists at this base.

Spaugh and I went up to look at the bombs, and I tore the whole back end out of my flying suit crawling through the bomb bay. We were hauling ten 500’s, big and blunt-nosed and ugly things. I patted one a couple of times and it felt cold and dead.

When all the guns were in we huddled up back by the tail. It was sort of like the locker room in high school before a ball game, only not so tense.

Crone said, “I hope those bastards come in on my side.”

Sharpe said, “I hope they all stay in the sack.”

Beach didn’t have anything to say at all. He was a sleepy guy, and older than the rest of us. For a minute he seemed closer than the others, just because he came from Denver, and we were so far from there.

I passed out the candy bars and the gum and the kits, and Sam cleared his throat.

“Okay,” he said, “this is our first one. We might as well make it good.”

Everyone looked all right, just a little tense, and tired of stalling around.

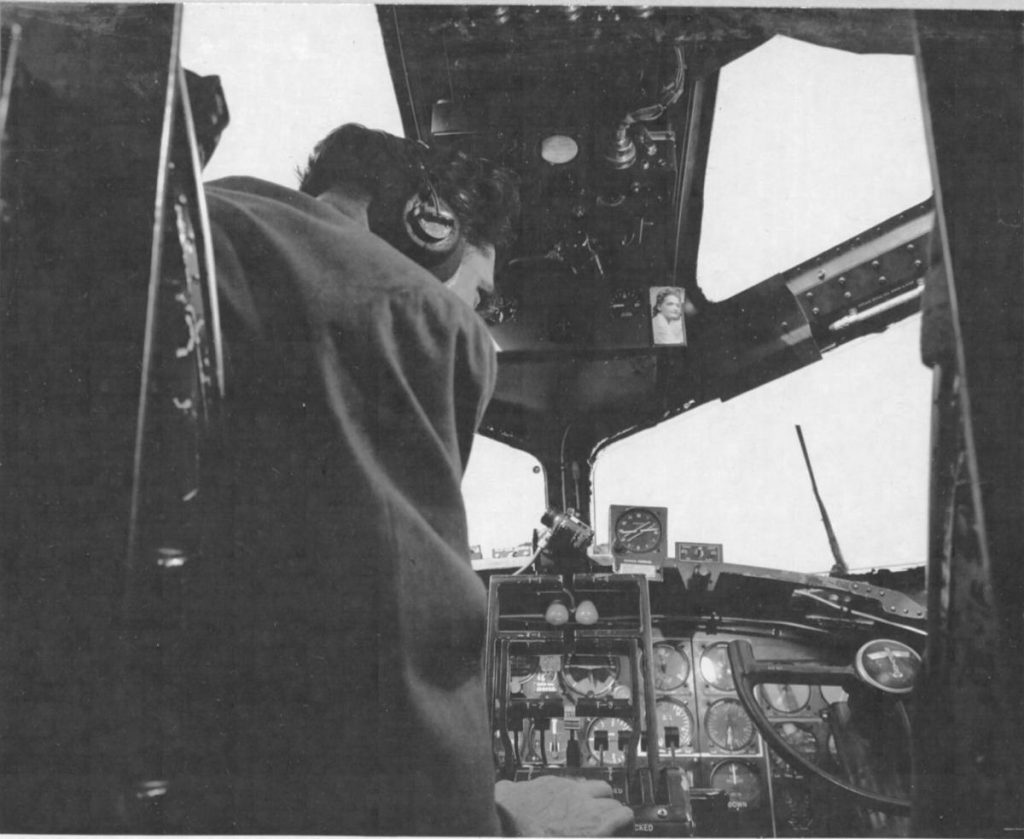

We started our engines at six o’clock. They kicked over right on down the line . . . start one, mesh one . . . start two . . . mesh two . . . good engines.

There was plenty of daylight when we got to take-off position. There were Forts stacked up there for blocks. They didn’t look very eager, just sitting there on their tail wheels. There were a lot of new silver ones, but the majority still had the old dirty brown-green paint on, like the Keystone Mama.

Then we moved out on the runway, everything set, and got the green light. I watched the instruments and called off the airspeed and Sam herded her down the runway. We were bouncing all over before the needle hit 120. Then Sam pulled her off, and we were airborne.

Grant gave me the heading over the interphone and we started climbing on course, away from the blood-colored dawn.

Sam and I had decided to trade off every fifteen minutes until we got used to going to war, but he flew most of the assembly, and I just changed the RPM when he called for it and sweated.

I thought the eighteen planes would never get together. We just flew around and around, getting nowhere, and then miraculously we were all in, flying off the right leaders, trying to look pretty.

We formed at seventeen thousand and my oxygen mask was bothering me, and my hair was soupy with sweat, and I couldn’t move my shoulders in my electric suit. It was too late to do anything though.

Our group got lined up in the wing formation, but some one was off somewhere, or some other wings were way out of line, because just as I was about to sit back and look around, we went driving through into another wing on a collision course. For a few seconds there were airplanes everywhere, and we were flopping around in prop wash. Sam was screaming inside his oxygen mask, and then they were gone.

I hadn’t even stopped breathing hard before it happened again.

Bird yelled over interphone, “Here they come!” I ducked and he said, “I don’t wanna die this way.”

Nobody got it head on, but nobody missed very far.

The air looked clear then, so Sam let me take it a while.

I held it in for a while and then started thinking about something or other, and when I came to we were way back out of formation. Sam grabbed the throttles, and I could hear him swearing into his oxygen mask.

“Get on the ball,” he said a minute later. “You gotta stay in there.”

Somewhere down in the formation the lead navigator was sweating out his check points, and the various squadron leaders were sweating out keeping their boys out of prop wash and in the right position, and all we had to do was hang on to that wing. But that was plenty. I was hot and my oxygen mask was trying to gag me, and I overcontrolled the throttles, too much, then too little, trying to fly that big bird close.

Sam could sit there and move the throttles a quarter of an inch once in a while and keep us in tight, unless he got careless. But I just didn’t have the touch. I made labor out of it. I heaved that big lady all over the sky, jockeying for position, eating up gas.

We flew up across the Channel and cut in at the Dutch coast. The navigator was on the ball, and we didn’t see any flak until we were out in the Zuider Zee. Some other wing navigator was asleep and they caught it right in the middle of the formation. Nobody went down. Pretty black puffs in a blue sky . . . harmless looking stuff.

We were flying into the sun, and our top window was so dirty I couldn’t see out of it at all. The front sheet of bullet proof wasn’t any too clean and it was rough trying to see anything into the sun.

Bird called for the oxygen check every ten minutes. We were numbered off from the tail. “One okay.”

“Two okay,” and so on up through ten in the nose. We sounded like a hot outfit.

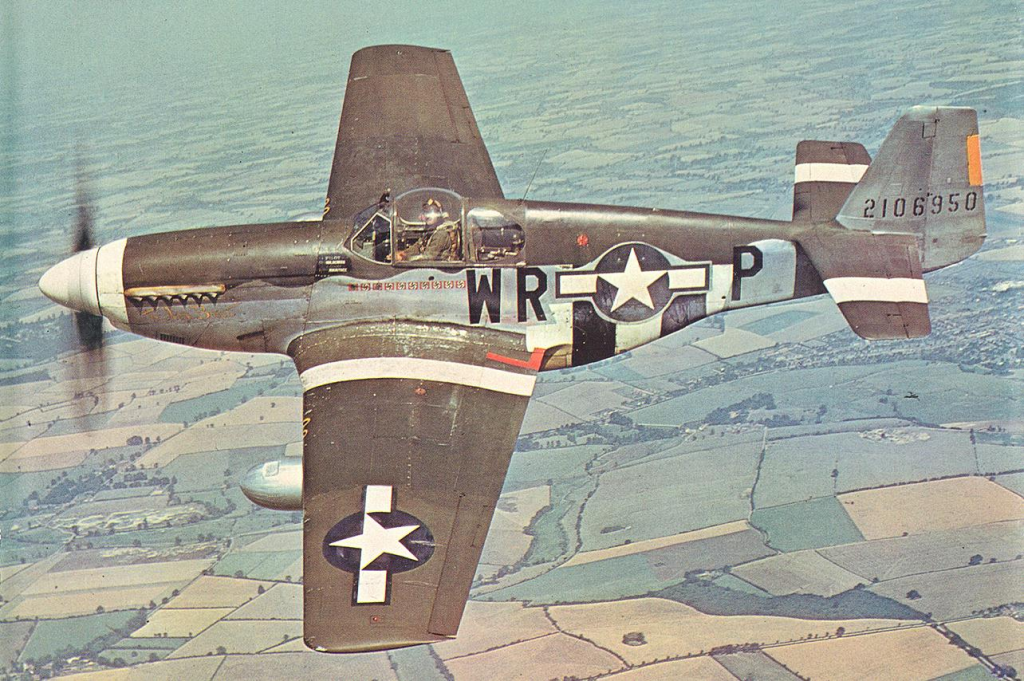

“Fighters, three o’clock, high,” came over interphone.

“They look like 47’s,” Bird said from the nose.

They were 47’s and they hustled on by into the sun.

“We’re over the Third Reich,” Benson announced.

The land was all chopped up into little fields and little towns. The fields were just as green as England, greener than Illinois when we crossed it last. They used the same sun down there, and the same moon. The sky was just as blue to them as to anyone at home probably. But for some reason the people down there were Nazis.

Sam signaled me to take the throttles for a while. The wing on our left was swinging in front of us, and it threw a wrench in the collective works. Everyone started chopping throttles back. I overran the lead and stayed throttles clear back too long. When I hit the power again we were faded.

I looked up into the sun and knew right then we were meat for the Luftwaffe. I could feel them up there waiting for a chance like this. I jacked up the RPM and poured on the gas and we moved back in slowly.

There were Forts everywhere, grouped into wings, winged into Air Divisions. The whole works was the 8th, Jimmy Doolittle’s Air Force.

Sharpe called off some flak at seven o’clock. “Look at that stuff,” he yelled. “It’s all over hell.”

“Take it easy on interphone,” Sam yelled at him.

Maybe our wing was off, maybe everyone was off a little. Anyway, wings started swinging in for their targets in front of us, behind us, and a couple of them tried to go through our formation while we were lining up for our bomb run.

I didn’t have any idea we were near the target until I saw the lead ship’s bomb bays swing open.

Benson said, “We’re at the I.P.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?” Bird said excitedly.

I thought we’d probably get left with a bomb load, but it turned out we had plenty of time for Bird to get ready to operate.

I crouched down, waiting for the flak to start. By all the rules there was supposed to be flak around us, right in our laps.

The bombs fell out of the lead ship and Bird yelled ours were gone.

“Radioman, see if all the bombs went,” Sam said.

“Wahoooooooo,” somebody yelled from the back end. “Look at that smoke.”

Everyone was talking at once. We had the RPM jacked up, swinging off the target. Still no flak.

“We missed it all to hell,” Bird said. “I couldn’t even see the target.”

All he had to do was toggle the bombs out when the leader let his go. Soft life.

Everyone was letting down a thousand feet so we could get out of the country a little sooner. A couple of wings off to the left were catching some flak and somebody had wiped out most of a town down to our right. We seemed to be out on the edge of the show.

“We’re in France now,” Benson called up. “We’re out of their goddamn country.”

I couldn’t tell the difference. From that high I couldn’t see that the people were all good guys. I did see a barn where I could hide if we had to bail out. Maybe there was a hayloft where some dark-eyed French girl was waiting with a couple of jugs of wine. Maybe there was a storm trooper with big boots and a bayonet to comb through the hay.

I decided to stay up high as long as possible.

There were quite a few airplanes in sight when we came in, but on the way out we saw thousands. Every direction up or down or sideways there were airplanes, big birds and little friends. There was one beat-up old B-24 straggling along down low with a couple of P-38’s hanging around for company.

“We’re over Belgium,” Benson called up after a while. “That big town is Brussels.”

It looked peaceful down there.

Then I remembered my flak suit stowed under the seat. It was a little late, but I put it on. Sam had climbed into his, way back over the Channel, coming in. It was heavy on my neck. I flew for a while until my neck began to bend in. My neck began to ache and my shoulder was sending in sympathy pains from time to time. Then I decided it wasn’t worth it and dumped the thing down in the catwalk.

Two P-51’s came jazzing by, looking for game.

I traded with Sam for a while and he went on the interphone. There was nothing but shrieks with static.

Then I heard this guy call in to the wing leader, “I’m going down. Our oxygen’s gone. Can you get us some escort?”

He was breathing like a horse. “My navigator’s shot to hell. I got to go down.” There was terror in his voice.

Up there somewhere in that soft blue sky a navigator was dying. It was pretty hard to believe.

The coast came in sight. Sometimes Crone or Sharpe would call off flak to the left or right, but we didn’t come even close.

There were three straggling 17’s down with the Liberators by then, but the fighters were herding them home.

“There’s a war on down there,” Sharpe said as we crossed the coast. “Look at all the blood.”

He couldn’t believe it and neither could I, but somewhere down there in that crazy patchwork of farms and towns and beaches there were some hard-eyed jokers who would have liked to get at us.

Sam was back on VHF. “Somebody’s dying,” he said to me. “Some navigator. This guy keeps calling up that his navigator is dying. What the hell good does that do?”

We started letting down when we crossed the coast. The formation began to loosen up a little. We’d heard a lot of stories about the old days, eight months ago, when the Abbeville Kids were waiting at the coast for loose formations. We stayed in.

At sixteen thousand I took off my helmet. There was a puddle of drool in my oxygen mask. I rubbed my face but it felt like a piece of fish. The candy bar tasted wonderful.

When we hit the English coast I was flying.

“Tighten it up a little,” Sam said. “They said to tighten it up.” He waved me in closer. “That navigator is still dying,” he said thoughtfully. “That guy keeps calling in.”

We were supposed to look sharp when we flew over some field at the coast, because Doolittle and Spaatz were down there watching and maybe Mr. Stettinius and Mr. Churchill were along as guests.

I don’t know how we looked. I know I didn’t care much. I’d never been so tired.

The navigator found the way home, and we circled the field while the low squadron peeled off.

I put the wheels down and Sam came in high and plunked us in halfway down the runway.

“We been to the war,” Sharpe said.

“We’re back now,” Bird said.

Back on that big wide runway. We put the Keystone Mama back where we got her and threw all the stuff out on the ground.

“Wonder if we killed anybody?” Lewis said.

“Wonder if we hit the fighter park?” Sam said.

I was so shot I didn’t want to move. My flying had been lousy. My hair was spongy with sweat and my eyes felt like they’d been sanded down and wrapped in a dry sack.

While I sat there a plane taxied by with half its tail blown off. It was one of ours. I didn’t believe it.

Lewis got his guns out, and I carried one of them over and put it on the truck for him.

Sharpe said, “Well, we’re not virgins anymore.”

“I still feel like one,” Crone said. “I didn’t see nothing.”

We’d been there and we were home. I lay back in a pile of flak suits and closed my eyes. There weren’t any holes in us, our tail wasn’t blown off. Right then I didn’t want to be anywhere else in the world, and these were the people I wanted to be with, these guys on this crew.

The equipment hut was jammed with guys and it smelled like a stable.

“How was it?” somebody said.

I turned around and there was the chaplain, the Catholic one.

“Milk run,” I said. “A joy ride.”

He smiled at me. He knew I was new. Then the smile went away.

“They got two,” he said. “Two whole crews are gone.”

He moved on to the next guy, but I heard someone else say they were out of the high composite.

We had put up part of another group and those guys were in the other one.

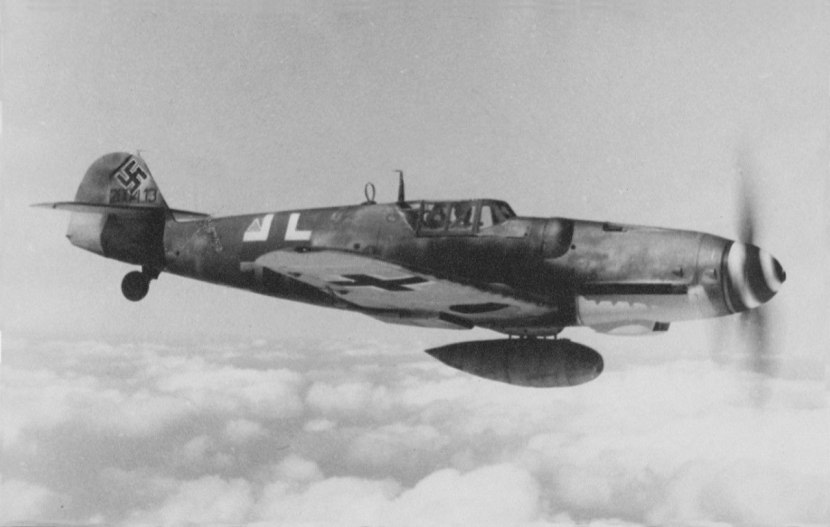

“They made a 360 at the target,” somebody said, “and the 109’s were up there in those clouds.”

Nobody saw the fighters. They came out of the sun, and they only made one pass. One Fort blew up and one went down burning. La French was one of them and the drunk co-pilot that woke me up the night before was in the other.

“That poor bastard could see it coming,” somebody said.

“He knew it was his turn.”

They were talking about that co-pilot.

But La French wasn’t like that. He was all alive the last time I saw him. He rode that bike of his like it was Seabiscuit. And now he was just blood and little chunks of bones and meat, blown all over the sky. Or he was cooked, burned into nothing.

I thought about him all through the interrogation. I drank three cups of coffee, but I couldn’t get him out of my mind.

A G.I. brought around a shot of scotch for each man on the crew. Lewis was sick and Beach was too tired, and Spaugh didn’t want any.

“I don’t like this goddamn English scotch,” Crone said. “It don’t taste like American scotch.”

“I’m not in the mood.” Bird pushed his away.

In the end I had a tall glass full of scotch and part of another one. I knew what was going to happen, but I drank it and chased it with coffee.

The room got warm and the sunlight turned deep gold. La French was gone but it was no good thinking about him any more. I was there and I was alive.

Billy Behrend came along on his bike when I went outside.

“It’s early,” he said. “Let’s go for a ride.”

I didn’t know him very well. He lived in the room across the hall, and he was always smiling.

We went down a road till it turned, and then we went the other way. There was a church with old gray walls and houses with thatched roofs and some little kids pulling a wagon full of milk bottles, and a muddy pond with dirty ducks in it.

There isn’t any way to tell how good it was to be there. Just to be moving, just to be riding down a road on a bicycle, and breathing and laughing once in a while, not knowing where the road led to and not caring. The world was endlessly big, and so green and soft and endlessly green.

We didn’t come back until late.

Man, I might have to get the book.

Good story. I will look for the book as well.