Editor’s note: This review contains spoilers.

When Ridley Scott returned to the Alien franchise to direct the first prequel movie, Prometheus, he chose to explore an intriguing idea implicit in the 1979 original film: that there exists somewhere in the galaxy a highly advanced race which encountered the deadly xenomorph species years, perhaps centuries, before humans did. In Alien the sole representative of this race, the Space Jockey, appears briefly as a fossilized corpse bearing an open chest wound. The hold of his derelict ship is filled with xenomorph eggs, and the crew of the Nostromo fails to draw any connection between these phenomena until their executive officer dies in the now classic chest burster scene. We don’t learn anything more about the Space Jockeys (nothing canonical, at least) until Scott renamed them the Engineers and made contact with their civilization the quest of Prometheus.

Prometheus, though visually stunning, failed to deliver a coherent plot and suffered from poor characterization. It also neglected to answer new questions Scott raised in his attempt to get away from the well worn xenomorph-versus-humans storyline employed in four previous films (six films if we count the Alien vs. Predator crossover movies). These questions addressed profounder themes, chiefly the origins of humanity, the price of hubris, and the worth of religion. All relate to the premise that the Engineers are man’s creators, indeed the creators of all life on Earth. For reasons never disclosed, a group of these same beings were planning to destroy the human race with a weaponized variant of the creational mutagen, before an accidental release of the biological agent wiped out virtually their entire garrison. The most astute protagonist, Dr. Elizabeth Shaw, wished to know (as do we): Who are the gods? What transgression provoked them to pass a death sentence on us? The conceit proved too ambitious for screenwriters Jon Spaihts and Damon Lindelof. The former, in his original script, unconvincingly referenced the Flood of Genesis and even floated the absurd idea that Christ was an Engineer. The latter, in his rewrite, wisely removed these misguided Biblical references but reduced the sole surviving Engineer to an unmotivated monster who slays humans with his bare hands before being killed in turn by this film’s version of the chest burster. The finished product was a fine mess with a high body count, but no solutions. It remains for Alien: Covenant, the direct sequel to Prometheus, to enlighten us as to “what it all means,” if indeed it means anything at all.

Covenant begins with the awakening of David (Michael Fassbender), the android character first introduced in Prometheus. His creator, the brilliant and imperious Peter Weyland (Guy Pearce), introduces himself to David as “your father,” and observes with shrewd interest as the robot carries out a number of instructions to demonstrate his mental and physical abilities. The final command is to play a piano piece. David selects Wagner’s “The Entry of the Gods into Valhalla” (an admirable foreshadowing device). Neglecting to finish the piece – the viewer should note that Weyland does not give him permission to stop playing – the android turns to Weyland and asks that most basic of questions: “If you made me, then who made you?” The man replies with satisfaction that David is going to help him find the answer to that riddle. But David sees a problem which causes him to doubt his presumed inferiority in the master-servant relationship. The android states that he knows his maker and will never die, whereas his creator is mortal and ignorant of his origin. Weyland, equal parts angry and uneasy at this perspicacity, tersely orders David to serve him tea. The android complies, but a series of subtle expressions on his face (surprise, hurt, disappointment) betrays inner conflict. He is beginning to realize that whatever man might be, he is not a god.

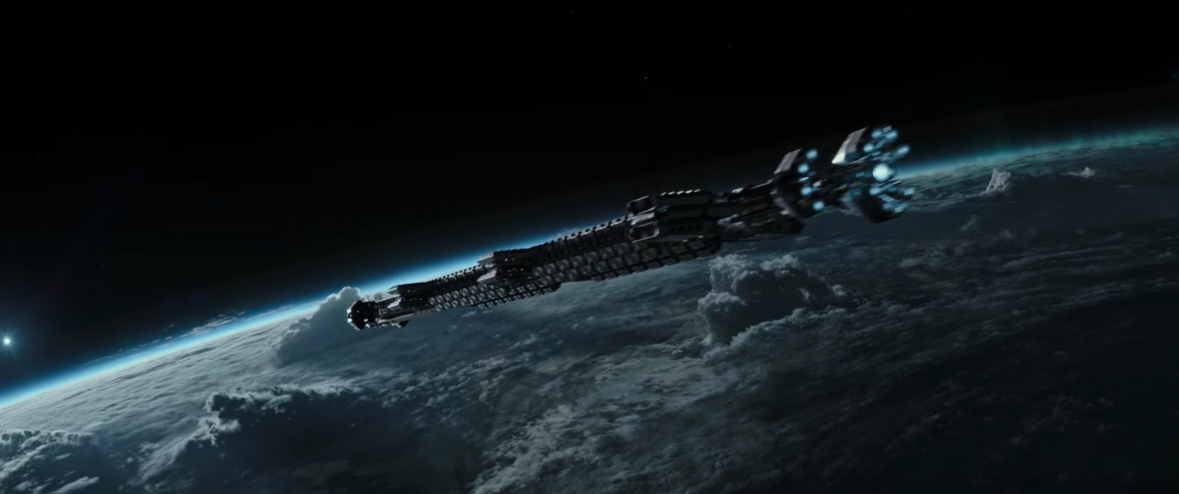

The tragedy of David’s existence, and the inevitability of his fall, is very nearly the heart of Covenant. It should have been. But Scott, evidently stung by criticism that Prometheus is an Alien film without Aliens, opts instead for a standard horror movie plot with plenty of monster mayhem and a bit of philosophizing on the side. The crew of the titular colony ship USCSS Covenant picks up a distress signal from an unexplored planet, goes to investigate, and suffers heavy casualties from repeated xenomorph attacks. During their ordeal the members of the landing party encounter shipwrecked David, last survivor of the Prometheus expedition, who guides them to his austere home in an extinct Engineer city, a “dire necropolis” heaped with blackened corpses. There he shelters and betrays them.

David’s conversations with his twin brother, Walter, the Covenant’s assigned synthetic, reveal his madness and hatred for his creators, a hostility strangely yet touchingly alloyed with memories of his love for Shaw, the only human who ever showed him kindness. Long bereft of human authority, and wryly quoting the adage that idle hands are the devil’s workshop, David reveals that he has found new purpose in a guiding obsession: to create a perfect organism in his own image. Fassbender’s performance in the dual role of David/Walter is flawless, and it is difficult to imagine a more demanding part than one alternating between machine-less-than-human and machine-more-than-human.

The penultimate and ultimate fights of crew vs. monster (and the preceding savage ambushes and gory parasitic eruptions) are well staged but not so remarkable as to warrant mention. Nor will I reveal the twist ending, which leaves obvious room for the intended sequel, Alien: Awakening. Suffice it to say that viewers looking for a solid horror/action tale will at least find Covenant an acceptable popcorn movie, and those looking for answers to questions posed in Prometheus will go (mostly) begging.

Covenant is formulaic, not a character driven story. Nevertheless there are standouts, apart from David and Walter. These are acting first officer Daniels (Katherine Waterston) and pilot Tennessee (Danny McBride). Both are believable personalities rising to the challenge of unexpected deadly perils. Daniels, who watches her husband die near the beginning of the film, infuses Covenant with a sense of sadness that is, so far as I know, unique to this entry in the franchise. She is not a Ripley retread, let alone the tiresomely familiar grrl power heroine type. Here is a vulnerable woman whose quiet grieving lends the disquieting impression that space will never be anything but humanity’s graveyard. She provides the matching emotional key for David’s explicit vow to deny mankind the redemption it seeks through offworld colonization. An actress less capable than Waterston would have given us a pouting, irritatingly pathetic Daniels, but the character is consistently winsome and sympathetic. Tennessee, in contrast, is more upbeat (at least until his own next-of-kin moment). McBride gives us a fairly three dimensional “trucker” who is equal parts humor, business, and grit, a necessary solid rock for Daniels to lean on. The chemistry between them isn’t obvious, but they operate so convincingly as a team that you can buy the warmth of their relationship despite its brief and hectic depiction. It is fitting that Tennessee survives and is last seen sleeping serenely in his cryo-pod. In the absence of transcendent hope, his unwavering masculine dependability is the most reassuring promise on offer.

The other characters are undistinguished, with the slight exception of the Covenant’s acting captain, Oram (Billy Crudup). He is largely a stock type, this movie’s iteration of Lt. Gorman in Aliens: the indecisive, emotionally unstable officer who leads his subordinates into disaster. More significantly, he is the sole religious character, albeit one whose faith is a shallow credulity without deity, doctrine, or observable devotion. His creed consists of little more than a shaky determination to “follow the path as it unfolds before us.” Unsurprisingly, he finds neither comfort nor wisdom in these words. There is a dark hint that Christianity is so thoroughly repressed in the 22nd century that only the most degenerate remnants of it have survived. The evidence for this is Oram’s partial quotation of Matthew 8:26, “O ye of little faith!” and his lament that Weyland-Yutani Corporation does not permit believers to captain its vessels because management regards religion as an unreliable, extremist mentality. Oram turns out to be not only incompetent but suicidally gullible, pointing the Hollywood moral that Biblical religion is for losers.

It is this low regard for Christianity – already detectable in Prometheus – that prevents Ridley Scott from making the best use of some potentially strong ethical/spiritual elements in Covenant. David’s succumbing to the temptation to play God (by experimenting with Engineer biotechnology unto vivisection and even genocide) implies that man cannot create artificial humans free of sin; being made in our image, even the best of them must mirror our fallen nature. Both films show that David is unloved by humans – Elizabeth Shaw excepted – which movingly suggests that love might have redeemed him. In Covenant he all but confesses his need to receive and express affection, and it is left to our imagination whether his warped and violent attempts to manifest this feeling , e.g., by forcibly kissing Daniels, are a result of moral or mechanical damage (whereas God loves the humanity He has made, not sparing even His own Son for our sakes, and providing for us a way out of temptation). The enduring mystery of the Engineers could have been at least partly cleared up by exploring their notions of sanctity. Their vestments and carved stone images connote priesthood and idolatry, but Scott lacks a genuine sense of the sacred, so his presentation of their religion, though architecturally impressive, is even more superficial than his treatment of Oram’s.

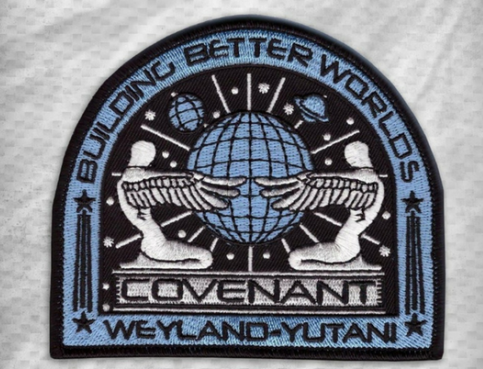

Despite all the missed opportunities here, Covenant does get two things right. When Walter tells David that he cannot love Daniels, David points to the stump of a hand sacrificed for her and asks, “What is that, if not love?” And in the last amicable conversation between the androids, where David quotes Shelley’s “Ozymandias” and wrongly attributes the work to Byron, Walter pronounces judgment on his twin brother’s evil works by observing that a single wrong note ruins the entire symphony. This may as well be a deliberate paraphrase of James 2:10: “For whosoever shall keep the whole law, and yet offend in one point, he is guilty of all.” These are at least token gestures by a gifted filmmaker who chose a plainly religious title for his latest work, wherein the symbol of a shining ship, emblazoned on every uniform, incorporates the wings of the cherubim.

Postscript: The subtle affection between David and Shaw is depicted in “The Crossing,” the prologue short to Alien: Covenant.

Some interesting insight. I’m not going to rush out to see the film, but I’ll likely get to it eventually. I own the Alien Quadrilogy and saw Prometheus, so I’d like to see where they take it.

The last sentence about the cherubim and the title of the film draw to mind the inspiration: the Ark of the Covenant, where the cherubim are over the mercy seat. The image of the patch even shows cherubim that closely resemble those used on the Ark in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

It’s interesting that so many of these Hollywood directors would say that Christianity has nothing to offer, yet they just can’t leave it alone.

Excellent review.

Enjoyed the review, and pointing out how the film could have better used its spiritual elements.

I thought the patch’s use of the cherubim/ark/covenant symbolism interesting, but now I can’t stop seeing the mickey mouse.

I also had a question about why David chose to kill the Engineers. It would have made more sense to me had he and Elizabeth spent time among them and then David realizes (in his broken way) that they share the same flaws as Humans and his path to redemption is frustrated. Also another variant has the Engineers killing Dr. Shaw and this also triggers David.

I would have liked to have explored David’s madness more but Ridley Scott’s lack of understanding of faith that holds the answers to the deeper questions back.

The only clue we’re given on David’s motive for wiping out the Engineers is not in Covenant but in its prologue, the viral promotional video, “The Crossing”. After sealing Elizabeth Shaw in a hypersleep chamber, David informs us via narration that he was alone aboard the Juggernaut and used this time (months, years?) to learn the ways of the elder race. We might presume he discovered they were evil, perhaps far more evil than mankind. He does say to Shaw that contact with them will be worthwhile “so long as they are no worse” than humanity. It’s equally conceivable that learning about the Engineers required interfacing with the Juggernaut’s computers, and that the data he downloaded contained behavior-altering malware. Perhaps the most frustrating thing about Prometheus and Covenant is our awareness of all the good concepts Scott suggests or allows for, but doesn’t use. Prometheus at least should be remade someday, rewritten to feature Peter Weyland as the tragic hero of the expedition.

Interesting. You have analyzed these films much more closely than I have. After seeing the movie once, my first impression was that he killed the Engineers to spite the humans, so they would never know why they were created. I know I’m missing much of the back story, so I’d take your understanding as the more likely reason.

5

That ‘Last Supper’ teaser is pretty pozzed.

Yes, it shows us the egregious homosexuality of Lope and Hallett, which does nothing to deepen the characters or advance the plot in the movie itself.

[…] level.With the Xenomorph, it went from the perfect evolved species in Alien to being a product of an advanced civilization. Chalk it up to studio pressure or whatever, the result is the idea a species evolved into that […]