Editor’s note: The following account by William R. St. Clair was published in the Confederate Veteran (January, 1894).

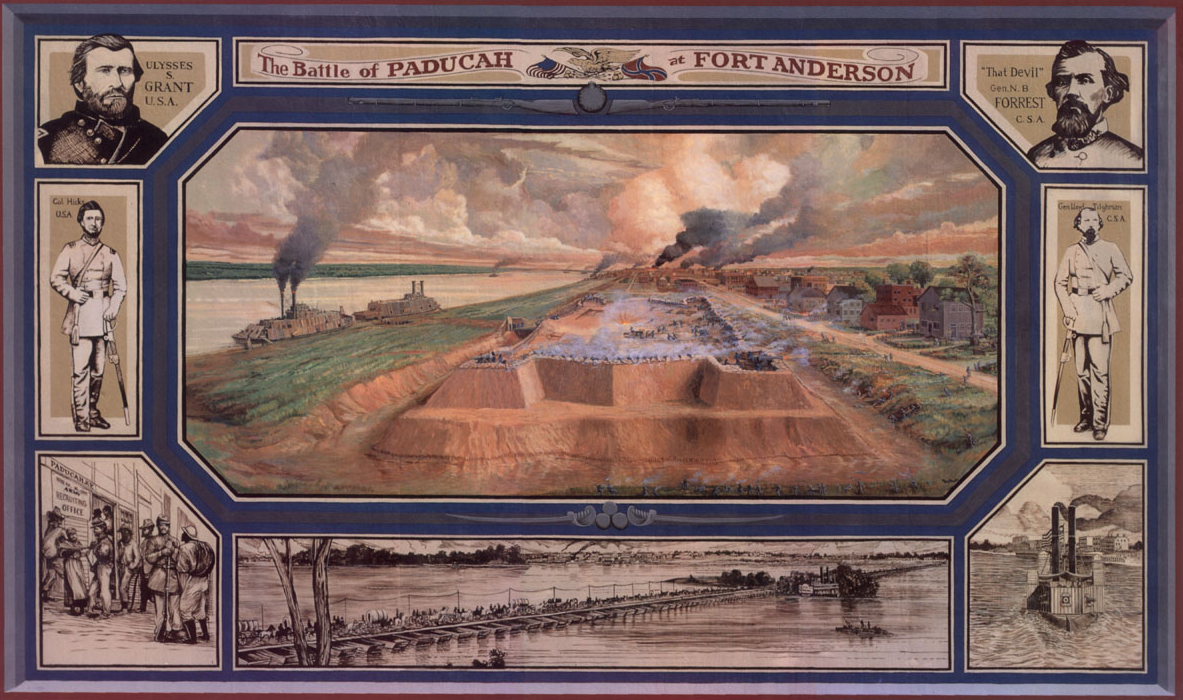

The following incident is but a remnant of the spice-box that, like pride, had a fall, or rather a more expeditious send-off during Gen. Forrest’s raid on Paducah, Ky.: Maj. Thompson led an attack on Fort Anderson, a huge affair, surrounding the Marine Hospital. Close by and overlooking the fort was the two-story brick building of Dr. Bassett. Some six or eight young Kentuckians, among whom were the Douglas and Meriwether boys, thought that this house presented some fine strategic points of value, both as a commissary department and “shooting-box;” the big 32-pounders in the fort could not be handled with any degree of safety if any party of sharp-shooters should happen to occupy the upper story. Accompanied by their Captain, the house was at once taken possession of, and Mrs. Bassett, delighted with the visit of the “Southern boys,” made at once extensive preparations for their comfort. The large dining table was taken up-stairs, for the greater convenience of her guests, and heaped with all the delicacies and good things that the house, cellar or pantry afforded. And nobly did the famished defenders of a lost cause respond to the tempting viands. The battle had now begun in earnest, and “the boys,” with their mouths full, sent their unerring missiles among the enemy’s cannoniers, to their utter discomfort and demoralization. The huge thirty-two in front of the house could not be fired. Every time a head appeared it was promptly scalped. The boys enjoyed the fun immensely, and divided their time between “shootin’ an’ eatin’.” After many failures, one artilleryman succeeded in pulling the lanyard, and a storm of grape and canister whistled through the house, without, however, touching the boys or the “vittels.” Douglas remarked that this was the best place to fight he had ever struck, and as long as the ammunition on the table held out he was willing “to fight it out on that line if it took all summer.”

The enemy made great efforts to reload the gun, but every time a man appeared a whistling messenger, laden with “pie,” stopped the performance. It had become intensely interesting and amusing on one side, and exceedingly dangerous on the other. The enemy soon realized the state of affairs, and took all available means to dislodge the sharp-shooters. The trouble was that the little band in the “Bassett house’’ had command of nearly every gun in the fort, and not only stopped proceedings against themselves, but hampered and annoyed the gunners on the opposite side, so as to prevent anything more than straggling shots, that did little or no execution. The gunboats, however, made active demonstrations in favor of the fort, and one of the shells, intended no doubt for the Bassett house, cut Maj. Thompson in two. But the end was nearer than “the boys” imagined. An unlucky shell from the enemy, striking a little lower, hit the edge of the table and made a promiscuous mingling of china, wood, meat, iron, vegetables, glassware and pie, the “tout ensemble” of a well-regulated dinner-table. It beat a “bull in the china-shop.” To see the beautiful walls plastered with pie, and the blackberry jam and preserves dripping mournfully from the ceiling was just a little too much for them. “Boys,” said Meriwether, “let’s go.” The Captain tearfully removed a lump of plum jelly from his eye and, said, “You’re right.” The defenders having left, the enemy immediately riddled the house with solid shot and grape, making a complete wreck of the noble building.

Meeting a refugee from the fort some months afterward, and regaling him with the narrative above stated, he remarked that he was one who tried to work that gun, and escaped the “rebel bullets;” “but,” says he, “I smelt the patching!” “How was that?” I answered. “Well, they sent a ball right under my nose, taking off a part of my mustache.”