Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Heroes of England, edited by John G. Edgar (published 1884).

Woodstock Palace presented a joyous scene on the morning of the 15th of June 1330. England’s queen, the excellent Philippa, had given birth to a son, thus realising the fond hopes of King Edward III, and fulfilling the ardent wishes of a loyal people. The peasant, the noble, and the king, rejoiced at his birth. In truth, the whole nation seemed to anticipate the future glory of the infant prince, and his baptism was celebrated with unequalled festivity. The young and beautiful mother nursed her own child, who, thus receiving health and strength from the same pure blood which had given him existence, seemed to imbibe the generous and feeling nature of Philippa; and, as he increased in vigour, he showed that he possessed the steady valour and keen sagacity of his father.

When three years of age, Prince Edward was made Earl of Chester. Four years after, he had a dukedom conferred on him—the first ever created in England. He was then styled Earl of Cornwall. On the day of installation, though only seven years of age, he dubbed twenty knights, as the first exercise of his new dignity. The title by which he became best known was not given him till he had reached his thirteenth year. He was then created Prince of Wales by his father, and invested in the presence of the Parliament with this dignity by the symbols of a coronet of gold, a ring, and a silver wand. From that time may be dated his entry into active life.

During the next three years, the prince was chiefly occupied in the practice of arms, and acquiring that skill in their use, and those powers of endurance, which were so necessary for the laborious and hazardous life of a knight in the days of chivalry. When sixteen, he accompanied his father in his expedition against France, and there soon saw in reality those scenes of which the tournament was but a sportive mockery. General battles were fought, in which the young prince shared; and the English army advanced into the interior of the country by some of the most daring and successful marches recorded in the annals of warfare.

At length the invaders encamped in a forest, a little to the west of the small town of Cressy. The French army, immensely superior in numbers, was not far distant; but, confident in his troops and himself, and animated by the memory of many triumphs, the King of England resolved to make a stand. The field of Cressy, from the capabilities of the ground, was chosen for the expected battle; and the plan being drawn out by Edward and his counsellors, the king, as the greatest and most chivalrous favour he could confer, determined to yield the place of danger and of honour to the prince, and, in his own words, “to let the day be his.”

To ensure his success, most of the famous knights were placed in the division which the Black Prince (as he was called, from the sable suit of armour he usually wore) was to command. The Earl of Warwick and the celebrated John Chandos were ordered not to quit his side, but be ever ready to direct and aid him.

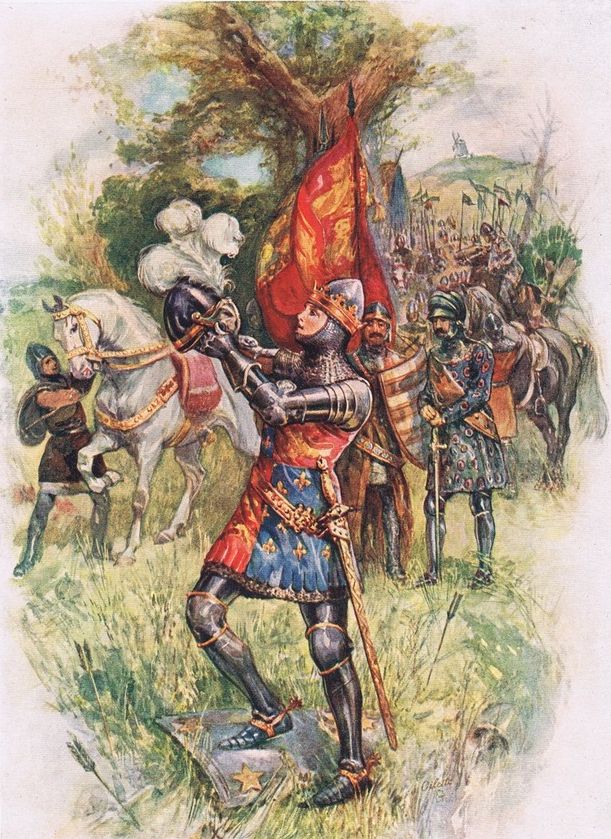

Early in the morning of the 26th of August 1346, the trumpets sounded, and the army marched to take up the position which had been selected on the previous day. The ground was an irregular slope, looking towards the south and east-the quarters from which the French were expected. The prince’s division, composed of eight hundred men-at-arms, four thousand archers, and six thousand Welsh foot, was stationed nearly at the bottom of the hill; the archers, as usual, in front, the light troops next, and then the men-at-arms, in the midst of whom was the prince himself, with twelve earls and lords, as his staff. To the left of this, and higher on the slope, appeared the second division, of about seven thousand men, commanded by the Earls of Arundel and Northampton. On a rising ground, surmounted by a windmill, aloof from the rest, was King Edward himself, with twelve thousand men as a reserve. The waggons and baggage were in the rear of the prince, under the charge of a small body of archers. As the battle was to be fought entirely on foot, all the horses were also left with the waggons.

Mounted on a palfrey, with a white staff in his hand, the king, with a smiling and cheerful countenance, rode from rank to rank. By noon he had passed through all the lines, exhorting the men to do their duty gallantly, and defend his honour and right. The soldiers now had permission to refresh themselves, while waiting the enemy’s approach. They accordingly ate and drank at ease, and afterwards lay down in ranks on the long grass, with their bows and steel caps beside them.

Meantime the French army had approached very near. Four knights had ridden forward and observed King Edward’s plan of battle; when, having seen how fresh and vigorous the English troops appeared, they advised Philip, the French king, to delay the engagement till next day, by which time his troops, now hungry and wearied, would be refreshed. Philip at once saw the wisdom of this counsel, and one of his marshals immediately galloped to the front, and the other to the rear.

“Halt your banners, in the name of God, the king, and St. Denis!” was the command given to the leaders. The advanced troops instantly obeyed: but the others pressed on, hoping to be among the foremost. This obliged the soldiers in front to move on again. In vain the king commanded, and the marshals threatened. Hurrying forward in disgraceful confusion, the French, passing through a small wood, suddenly found themselves in the presence of the English. The surprise caused the first line to fall back, and thus increased the confusion, while the English soldiers rose steadily from the grass, and stood in fair and martial order on the hillside, with the standard of the Black Prince in their front.

The sky had by this time become clouded; a thunderstorm came on, and torrents of rain soon fell—slackening the strings of the cross-bows of the Genoese archers, who had advanced to break the firm front of the English bowmen. The clouds cleared quickly away, and the western sun soon shone out bright and clear, full in the faces of the French. At length the Genoese bowmen drew their arblasts, and commenced their discharge, and each English archer stepped forward a single pace, as he took his bow from the case in which it had been protected from the rain. A flight of arrows then fell among the Genoese, piercing their heads, arms, and faces, and causing them instantly to retreat in confusion among the horsemen in their rear.

The passionate French king, instead of trying to rally the fugitives, at once ordered the men-at-arms to fall upon them. The cavalry, the heavy troops, and the cross-bowmen soon formed a wild and reeling crowd, amid which the English poured a continued flight of unerring arrows, and not a single bow-string was drawn in vain.

Meantime the Count of Alençon, dividing his men into two parties, swept round on one side of this scene of confusion; while the Count of Flanders did the same on the other side, and, avoiding the archers, furiously attacked the men-at-arms around the prince. England’s chivalry, headed by the gallant prince, met the impetuous charge with equal valour and with greater success; and, as each headlong effort of the French deranged the ranks for a moment, they were formed anew, each man fighting where he stood, none quitting his place to make a prisoner, while growing piles of dead told of their courage and vigour. The two counts were slain, and terror began to spread through their troops. A large body of German cavalry now bore down on the prince’s archers, and, in spite of the terrible flight of arrows, cut their way through and charged the men-at-arms. By this time nearly forty thousand men were pressing round the little English phalanx; but the combat was renewed, hand to hand, with more energy than ever, while the Earls of Northampton and Arundel moved up with their division, to repel the tremendous attack.

King Edward still remained with his powerful reserve, watching the battle from the windmill above. The Earl of Warwick now called a knight, named Thomas of Norwich, and despatched him to the king.

“How now, Sir Thomas?” inquired Edward, as the knight reached the royal presence; “does the battle go against my son?”

“No, sire,” replied Sir Thomas; “but he is assailed by an overpowering force, and the Earl of Warwick prays the immediate aid of your grace’s division.”

“Sir Thomas,” demanded Edward, “is my son killed or overthrown, or wounded beyond help?”

“Not so, my liege,” answered the knight; “yet he is in a rude shock of arms, and much does he need your aid.”

“Go back, Sir Thomas, to those who sent you,” rejoined the king, “and tell them from me, that whatever happens, to require no aid from me so long as my son is in life. Tell them, also, that I command them to let the boy win his spurs; for God willing, the day shall be his, and the honour shall rest with him, and those into whose charge I have given him.”

The prince, and those around him, seemed inspired with fresh courage by this message; and efforts surpassing all that had preceded were made by the English soldiers. The French men-at-arms, as they still dashed down on the ranks, met the same fate as their predecessors; and, hurled wounded from their dying horses, were thrust through by the short lances of the half-armed Welshmen, who rushed hither and thither through the midst of the fight. Charles of Luxembourg, King of the Romans, who led the German cavalry, seeing his banner down, his friends slain, his troops routed, and himself wounded severely in three places, fled, after casting off his rich surcoat, to avoid recognition.

This prince’s father, who figured as King of Bohemia, was seated on horseback, at a little distance from the fight. The old man had fought in almost every quarter of Europe; and he was still full of valour, but quite blind. Unable to mark the progress of the contest, the veteran continued to inquire anxiously, and grew indignant at his ally being vanquished by a warrior in his teens. “My son,” demanded the veteran monarch of his attendants, “my son!—can you still see my son?”

“The King of the Romans is not in sight, sire,” was the reply; “but doubtless he is somewhere engaged in the melée.”

“Lords,” continued the old king, drawing his own conclusions from what he heard, and resolved not to quit the field alive, “Lords, you are my vassals, my friends, and my companions, and on this day I command and beseech you to lead me forward so far that I may deal one blow of my sword in the battle.”

They linked their horses’ bridles to one another, and placing their venerable lord in the centre, galloped down into the field. Entering the thickest strife, they advanced directly against the Prince of Wales. The old blind monarch was seen fighting valiantly for some time, but at length his banner went down. Next day he was found dead on the field of Cressy, his lords around him, their horses still linked to each other by the bridles.

It was growing dark ere the fiery Philip could force his way through the confusion he had himself chiefly caused by the imprudent command he gave at the commencement of the battle. The unremitting arrows of the English still continued to pour like hail, and the followers of Philip fell thickly around. Many fled, leaving him to his fate; and presently his own horse was killed by an arrow.

One of his attendants, John of Hainault, who had remained by his side the whole day, mounted him on one of his own chargers, and entreated him to quit the field. Philip refused; and making his way into the thickest battle, fought for some time with great courage. At length when his troops were almost annihilated, and when he was wounded, the vanquished king suffered himself to be led from the field; and with a few of his lords, and only sixty men-at-arms, reached his nearest castle of Broye in safety. At midnight he again set out, and did not slacken his flight till he reached Amiens.

The boy Prince of Wales still held his station firmly in the battle; the utmost efforts of the French had not made him yield a single step. By degrees, as night fell, the assailants decreased in number, the banners disappeared, and the shouts of the knights and the clang of arms died away. Silence at last crept over the field, and told that victory was completed by the flight of the enemy. Torches were then lighted in immense numbers along the English lines to dispel the darkness.

King Edward now first quitted his station on the hill; he hastily sought his conquering boy, and clasped him proudly to his bosom.

“God give you perseverance in your course, my child!” cried the king, as he still held him. “You are indeed my son! Nobly have you acquitted yourself, and worthy are you of the place you hold!”

The youthful hero had hitherto, in the excitement and energy of the battle, felt only the necessity of immense exertion, and had been unmindful of all but the immediate efforts of the moment. Now, however, the thought of his great victory, which his father’s praise seemed first to bring fully to his mind, overcame him, and he sank on his knees before the king and entreated his blessing after a day of such glory and peril. And thus ended the battle of Cressy.

The prince had fully established his character as a warrior. Two or three years afterwards he showed that he could display equal courage at sea as on land. This was in an engagement with the Spaniards.

Peter the Cruel, as he was termed, was at that time King of Castile, and encouraged to a great extent the pirates who infested the English seas. His own ships, even in passing through the British Channel, had captured a number of English merchantmen returning from Bordeaux, and, after putting into Sluys, were preparing to sail back in triumph with the prizes and merchandise.

King Edward determined to oppose their return, and collected his fleet off the coast of Sussex, near Winchelsea. When he heard that the Spaniards were about putting to sea, he immediately embarked to command the expedition in person. The Black Prince, now in his twentieth year, accompanied him, and commanded one of the largest vessels. The day on which the Spanish fleet would make its appearance had been nicely calculated. Edward waited impatiently for its approach, and to beguile the time made the musicians play an air which the famous Chandos, who was now with him, had brought from Germany.

“Now, Sir Knight,” said the monarch sportively, “thou hast a mellow voice; we command thee to sing the air with the musicians.”

The knight obeyed, though somewhat reluctantly. During the concert the king from time to time turned his eye to the watcher at the mast-head. In a short time the music was interrupted by the cry of “A sail!”

Ordering wine to be brought, Edward drank one cup with his knights, and throwing off the cap he had worn till now, put on his casque, and closed his visor for the day.

The Spanish ships came on in gallant trim. The number of fighting men which they contained was, compared with the English, as ten to one, and their vessels were of a much greater size. They had also large wooden towers on board, filled with cross-bowmen, and were further provided with immense bars of iron with which to sink the ships of their opponents. They approached, with their tops filled with cross-bowmen and engineers, the decks covered with men-at-arms, and with the banners and pennons of different knights and commanders flying from every mast. They came up in order of battle a few hours before night. King Edward immediately steered direct against a large Spanish ship, endeavouring, according to the custom of ancient naval warfare, to run her down with his prow. The vessel, which was much superior to his own in magnitude, withstood the tremendous shock, both ships recoiling from each other. The king now found his ship had sprung a leak, and was sinking fast. In the confusion the Spanish vessel passed on; but Edward, immediately ordering his ship to be lashed to another of the enemy, after a desperate struggle made himself master of a sound vessel.

The battle now raged on all sides. Showers of bolts and quarrels from the cross-bows, and immense stones, hurled by powerful engines, were poured upon the English. The Black Prince, imitating the example of his father, had fixed on one of the largest ships of the enemy; but, while steering towards her, the missiles she discharged pierced his own vessel in several places. The speedy capture of his enemy was now necessary; for, as he came alongside, his bark was absolutely sinking. The sides of his opponent’s vessel being much higher than his own, rendered the attempt very hazardous; and while, sword in hand, he attempted to force his way, bolts and arrows poured on his head from every quarter. The Earl of Lancaster, sweeping by to engage one of the enemy, perceived the situation of the prince, and immediately dashed to the other side of his antagonist. After a fierce but short struggle, the Spanish ship remained in the hands of the prince; and scarcely had he and his crew left their own vessel, before she filled and went down.

Twenty-four of the enemy’s ships had by this time been captured; the rest were sunk, or in full flight; and, night having fallen, King Edward measured back the short distance to the shore. Father and son, then mounting horse, rode to the Abbey of Winchelsea, where Queen Philippa had been left, and soon turned the suspense she had suffered, since darkness had hidden the battle from her sight, into joy and gratitude.

Philip, King of France, was now dead, and his eldest son, John, occupied the throne. Some proceedings on the part of the new monarch were regarded as a signal to break the truce which had subsisted for a short time between the English and French. Various displays of hostilities followed, and many negotiations were entered into without success. At length, the Black Prince, being appointed captain-general, sailed for Bordeaux in August 1335, and arrived there after an easy passage. His first movements were successful; and even when winter set in, the judicious manner in which he employed his troops enabled him to add five fortified towns and seventeen castles to the English possessions.

When spring and summer had passed by—the prince still continuing active—the French king collected an immense army, and marched to intercept the invaders. Though well aware that John was endeavouring to cut off his retreat, the Black Prince was ignorant of the exact position of the French army, until, one day, a small foraging party fell in with a troop of three hundred horsemen, who, pursuing the little band across some bushes, suddenly found themselves under the banner of the Black Prince. After a few blows they surrendered, and from them the prince learned that King John was a day’s march in advance of him.

A party despatched to reconnoitre, brought back intelligence that an army of eight times the English force lay between them and Poitiers. Though without fear, the prince felt all the difficulties of his situation; yet his simple reply was—“God be our help!—now, let us think how we may fight them to the best advantage.”

Some high ground commanding the country towards Poitiers, defended by the hedges of a vineyard, and accessible from the city only by a hollow way, scarcely wide enough to admit four men abreast, presented to him a most defensible position. Here the prince encamped, and next morning disposed his troops for battle. He dismounted his whole force; placed a body of archers, drawn up in the form of a harrow, in front, the men-at- arms behind, and stationed strong bodies of bowmen along the hedges, on each side of the hollow way. Thus, while climbing the hill, the French would be exposed to the galling flights of arrows; while the nature of the ground would further render their superiority in numbers of little avail.

The French, sixty thousand strong, were now ready to march. The oriflamme, or great banner of France, had been displayed, and the whole army was eagerly waiting the word of command to crush the handful of enemies which crowned the hill before them, when the Cardinal de Perigord rode hastily along their ranks. He was regarded with an evil eye, for the men knew his was an errand of peace.

The good cardinal found King John in the midst of waving banners, nodding plumes, glittering arms, and all the pomp of royalty, combined with the splendour of feudal war. As soon as he saw the king, the cardinal dismounted, and, clasping his hands, besought him to give him audience before he commanded the march.

“Willingly, my Lord Cardinal,” the king answered: “what have you to say?”

“Sire,” replied the legate, “you have here all the chivalry of your realm assembled against a handful of English :—consider, then, will it not be more honourable and profitable for you to have them in your power without battle, than to risk such a noble army in uncertain strife? Let me, I pray you, in the name of God, ride on to the Prince of Wales—show him his peril, and exhort him to peace.”

“I grant your request, my lord,” replied the king; “but let your mission be speedy.”

Without staying a moment, the cardinal hastened on to the Black Prince, whom he found also armed and ready for battle, yet not unwilling to hearken to proposals of peace. The superiority of the enemy, if they chose to blockade him in his position, rendered him apprehensive that he might be obliged then to surrender unconditionally.

“My Lord Cardinal,” he replied at once, “I am willing to listen to any terms by which my honour, and that of my companions, will be preserved.”

The cardinal returned to King John with this answer, and, after much entreaty, obtained a truce till next morning. John, however, would hear of nothing but an unconditional surrender. To this the Black Prince would not consent, although he offered to resign all he had captured in his expedition—towns, castles, and prisoners—and to take an oath that for seven entire years he would not bear arms against France.

“Fair son,” said the cardinal, when, after finding John inflexible, he sought the Black Prince for the last time; “fair son, do as you best can, for you must needs fight, as I can find no means of peace or amnesty with the King of France.”

“Be it so, good father!” replied the heroic prince; “it is our full resolve to fight; and God will aid the right.”

The French host now began to advance; yet, as its ocean of waving plumes rolled up the hill, the prince, in the same firm tone which had declared, the day before, that England should never have to pay his ransom, now spoke the hope of victory.

Three hundred horsemen, the pick of the French army, soon reached the narrow way, and spurring their horses, poured in at full gallop to charge the harrow of archers. The instant they were completely within the banks, the English bowmen along the hedges poured a flight of arrows, which threw them instantly into confusion. The bodies of the slain men and horses soon blocked up the way; but a considerable number, forcing a path through every obstacle, nearly approached the first line of archers. A gallant knight, named James Audley, with his four squires, rushed against them. Thus, almost single-handed, he fought during the whole day, hewing a path through the thickest of the enemy. Late in the evening, when covered with many wounds, and fainting from loss of blood, he was borne from the field.

Meantime, the shower of arrows continued to pour death, while the English men-at-arms, passing between the lines of the archers, drove back the foremost of the enemy, and the hollow became one scene of carnage. One of Edward’s officers, known as the Captal de Buch, at the same time issued from a woody ravine situated near the foot of the hill—where, with three hundred men-at-arms and three hundred archers on horseback, he had lain concealed—and attacked the flank of one of the divisions of the French army, commanded by the dauphin, as it commenced the ascent. This, with the confusion in front, and a rumour that part of the army was beaten, carried terror into the rear ranks; and vast numbers, who had hardly seen an enemy, gained their horses with all speed, and galloped madly from the field. The arrows discharged by the horse-archers now began to tell on the front line of the enemy; the quick eye of John Chandos marked it waver and open.

“Now, sir,” he exclaimed, turning to the prince, “ride forward, and the day is yours. Let us charge right upon the King of France, for there lies the fate of the day. His courage, I know well, will not let him fly; but he Ishall be well encountered.”

“On! on! John Chandos!” replied the prince; “you shall not see me tread one step back, but ever in advance. Bear on my banner! God and St. George be with us!”

The horses had been kept in readiness; and, each man now springing into his saddle, the army bore down on the enemy with levelled lances; the Captal de Buch forcing his way onward to regain the main body. The hostile forces met with a terrible shock, while the cries of “Denis Mountjoye!” “St. George Guyenne!” mingled with the clashing of steel, the shivering of lances, and the sound of the galloping steeds. The sight of the conflict struck terror into a body of sixteen thousand men, who had not yet drawn a sword. Panic seized them; and these fresh troops, instead of aiding their companions, fled disgracefully with their commander, the Duke of Orleans. This probably decided the day.

King John was now seen advancing with his reserve in numbers still double the force of the English at the commencement of the battle. He saw his nobles flying, but, though indignant, felt no alarm. Dismounting with all his men, he led them, battle-axe in hand, against the English charge. The sable armour of the Prince of Wales rendered him also conspicuous; and, while the French king did feats of valour enough to win twenty battles, if courage could have done all, the young hero of England was seen raging like a lion amid the thickest of the enemy. Knight to knight, and hand to hand, the battle was now fought. The French were driven back, step by step, till King John found himself nearly at the gates of Poitiers, which were now shut against him. While, however, the oriflamme waved over his head, he would not believe the day lost; but at length it went down, and with it his hopes fell. Surrounded on every side by foes eager to make him prisoner, he still wielded his battle-axe, clearing at each stroke the space around him and his little son, who had accompanied him through the fatal field. A knight of Artois, of gigantic height, who had been outlawed, and had taken service with England, seeing that the monarch’s life would be lost if he protracted his resistance, suddenly rushed into the circle.

“Yield, sire, yield!” he exclaimed in French.

“To whom shall I yield?” demanded John. Where is my cousin the Prince of Wales? Did I see him I would speak.”

“He is not here, sire,” replied the knight; “but yield to me, and I will bring you safely to him.”

“Who art thou?” inquired John.

“I am Denis de Mortbec, a poor knight of Artois,” answered the outlaw, “but now in the service of England, because a banished man from my own country.”

“Well, I yield me to you,” cried the king, giving him, in sign of surrender, his right gauntlet.

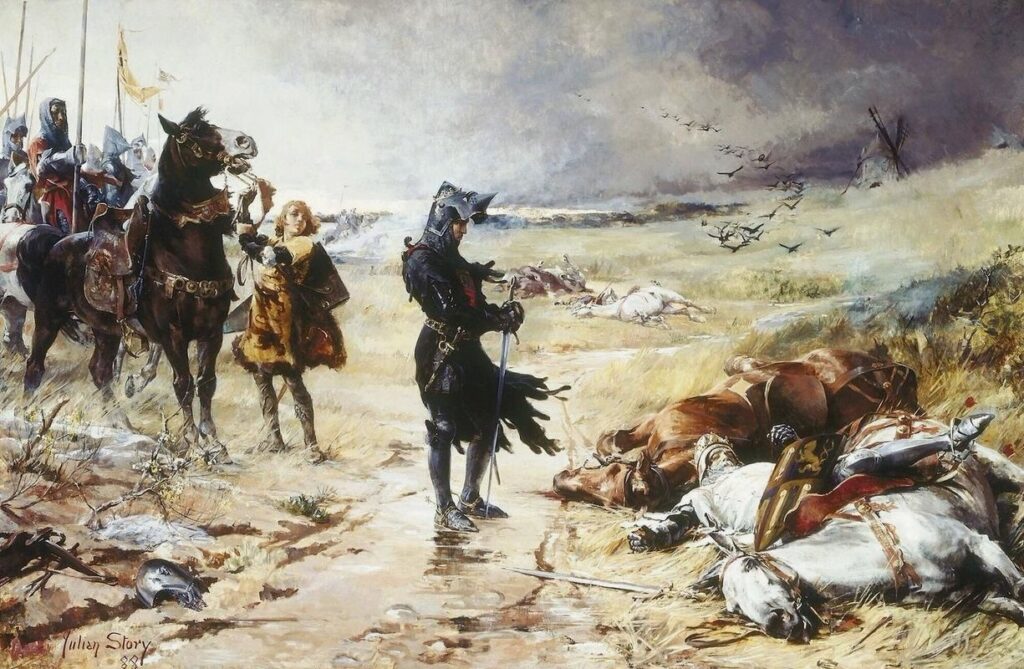

By this time nothing was seen but dead and dying on the field, with groups of prisoners, and parties of fugitives escaping over the distant country. The prince, by the advice of Chandos, now pitched his banner on a high spot; and, while the trumpets sounded a recall to the standard, he dismounted, and, unbracing his helmet, took a draught of wine with the band of knights who had accompanied him throughout the arduous day.

The unfortunate French king was soon brought to the victor by the Earl of Warwick and Lord Cobham, whom he had despatched in search as soon as he learned that the monarch had not quitted the field. He had been snatched from the charge of Denis de Mortbec; and, when the lords arrived, they found his life in great danger, from the eagerness those around him showed in each claiming him as a prisoner. The prince received his vanquished adversary with deep and touching respect. Bending his knee before John, he called for wine, and, with his own hands, presented the cup to the unhappy king.

By mid-day the battle was over; but, as the pursuing parties did not return till the evening, it was only then that the prince learned the greatness of his victory. With eight thousand men he had vanquished more than sixty thousand, and the captives were double the number of the conquerors. Thus was won the most extraordinary victory the annals of the world can produce.

At night a sumptuous entertainment was served in the tent of the Black Prince to the principal prisoners. King John, with his son, and six of his chief nobles, were seated at a table raised higher than the rest; but no place was reserved for the prince himself. Great was the surprise when the victor appeared to officiate as page. This, in the days of chivalry, implied no degradation, though it showed the generous humility of the young hero. The captive monarch repeatedly entreated the prince to seat himself beside him, and could scarcely be persuaded to taste the food while his conqueror remained standing, or handed him the cup on bended knee. The respectful manner in which the prince conducted himself, and the feeling he expressed for the misfortune of his foe, so touched John, that at last the tears burst from his eyes, and mingled with the marks of blood on his cheeks.

The example of the Black Prince was followed throughout the English camp; every one treating his prisoner as a friend, and admitting him to ransom on terms named, in most cases, by the vanquished.

London presented a gay spectacle on the 24th of May 1357. On the morning of that day the prince entered its gate, proceeding through the city on his way to Westminster. The streets were tapestried with the finest silks and carpets, while trophies of every kind of arms were displayed before the houses. The French king, splendidly attired, was mounted on a superb white charger; while his conqueror, simply clothed, rode on a black pony by his side. In the great hall of the palace at Westminster, Edward III received the royal prisoner in state, embracing him and bidding him be of good cheer. The palace of the Savoy was then appointed for his residence, and every kindness was added to soften his captivity in a strange land. Four years afterwards, during which time he had been treated like a royal visitor, he was set at liberty, at the signing of the treaty of Bretigny.

It appears that at an early period of his life the hero of Poitiers had been inspired with a tender regard for his kinswoman, Joan Plantagenet, daughter of Edmund, Earl of Kent. Unfortunately, this lady, known as “The Fair Maid of Kent,” had not been particularly circumspect in her conduct; and Edward and Philippa could not think of their heir being united to a woman of whom scandal whispered some very light tales. A marriage being thus, as it were, precluded, Joan gave her hand to Sir Thomas Holland. After some years the knight died; and a story is told of the way in which the love of the Prince of Wales was rekindled.

An English noble, whose name history does not give, so runs the story, had fallen in love with the fair widow; and, finding his suit tardy, he entreated the good word of the prince. While pleading the cause of his friend, Edward felt his old tenderness return; and, on the 10th of October 1361, he was united to Joan at Windsor. The unfortunate king, Richard II, born at Bordeaux, was the fruit of this marriage.

After this event the prince again distinguished himself in France; for the claims of his father, which the treaty had in part recognised, were fiercely disputed. Many battles were fought, and much negotiation was carried on, extending over several years. While in the midst of these harassing circumstances, the prince, who had been long ill, became worse. His surgeons advised his return to England. He complied; but day after day his strength failed him, and fainting fits of long continuance often led those around him to suppose him dead. At length, on Sunday, the 8th of June 1376, he closed a life which for years had been one sad scene of suffering. He was interred with due pomp in Canterbury Cathedral, his favourite suit of black armour being suspended over his tomb. Thus, scarcely past his prime, died “the valiant and gentle Prince of Wales, the flower of all chivalry in the world at that time.”

Would more of our leaders be like the Black Prince and King Edward, both ours and our opponents.