Editor’s Note: The following is extracted from Oom Paul’s People, A Narrative of the British-Boer Troubles in South Africa, by Howard C. Hillegas (published 1900)

The early history of the Boers is contemporaneous with that of the progress of white man’s civilization at the Cape of Good Hope. The two are interwoven to such an extent and for so long a time that it is well-nigh impossible to separate them. In order to give an unwearisome history of the modern Boer’s ancestors, a general outline of the settlement of the Cape will suffice.

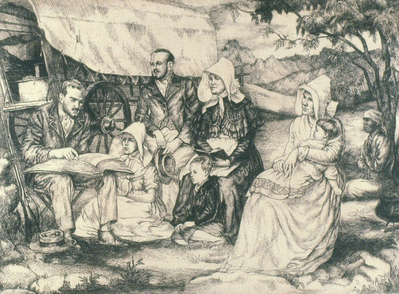

The history of the Boers of South Africa has its parallel in that of the early Pilgrims who landed at Plymouth Rock and their descendants. The comparison favours the latter, it is true, but the conditions which confronted the early Boers were so much less favourable that their lack of realization may easily be accounted for. In the early part of the seventeenth century the progenitors of the Boers and the Pilgrims left their continental homes to seek freedom from religious tyranny on foreign shores.

The boat load of Pilgrims left England to come to America and found the freedom they sought. About the same time a small number of Dutch and Huguenot refugees from France departed from Holland for similar reasons, and decided to seek their fortunes and religious freedom at the Cape of Good Hope. There they found the liberty they desired, and, like the Pilgrims, assiduously set to work to clear the land and institute the works of a civilized community.

The experiences of the two widely separated colonists appear painfully similar, although to them they were undoubtedly preferable to the persecutions inflicted upon them in their native countries. The Pilgrims were constantly harassed by the savage Indians; the Dutch and Huguenots at the Cape had treacherous Hottentots and Bushmen to contend against. Although probably ignorant of each other’s existence, the two parties conducted their affairs on similar lines and reached a common result—a good local government and a reasonable state of material prosperity.

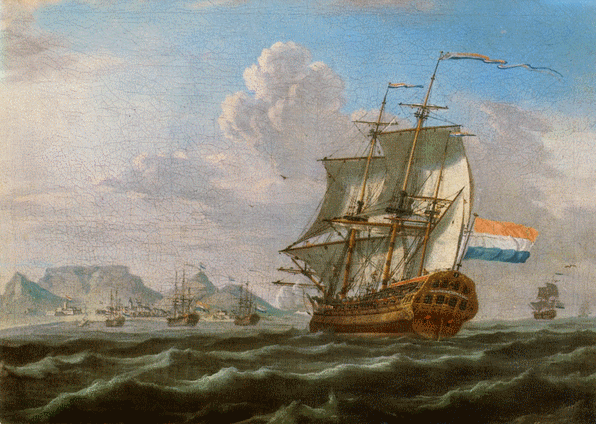

The little South African settlement became of recognised importance in the later years of the century, when it was made the halfway station of all ships going to and returning from the East Indies. The necessity for such a station was the foundation of the growth of the settlement at Table Bay, which is only a short distance from the southernmost extremity of the continent, and the increase in population came as a natural sequence.

The Dutch East India Settlement, as it was officially called, attracted hundreds of immigrants. The reports of a salubrious climate, good soil, and, more than all, the promised religious toleration, were the allurements that brought more immigrants from Holland, Germany, and France. Cape Town even then was one of the most important ports in the world, owing to its great strategic value and to the fact that it was about the only port where vessels making the long trip to the East Indies could secure even the scantiest supplies. The provisioning of ships was responsible in no small degree, for the growth of Cape Town and the coincident increase in immigration.

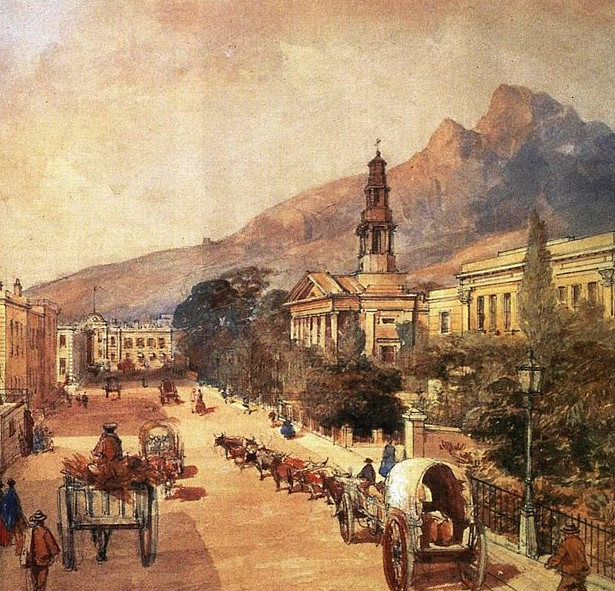

When all the available land between Table Mountain and Table Bay was settled, the new arrivals naturally took up the land to the northward, and drove the bellicose natives before them. Like their Pilgrim prototypes, they instituted military organizations to cope with the natives, and they were not infrequently called upon for active duty against them. It was owing to this savage disposition of the natives that the settlers confined their endeavours to the vicinity of Table Bay.

When immigrants became more numerous and land increased in value, the pilgrims of more daring disposition proceeded inland, and soon carried the northeastern boundary of the settlement close to the Orange River. The soil around Table Bay was extremely rich, but farther inland it became barren and, by reason of the many lofty tablelands, almost uninhabitable. The Bushmen, too, were constantly attacking the encroaching settlers, whose lives were filled with anything but thoughts of safety, and high in the northern side of Table Mountain is to be seen to-day an old-time fort that was erected by the settlers to ward off natives’ attacks upon Cape Town.

The Dutch East India Company, which controlled the settlement, looked with disfavour upon the enlargement of the original boundary of the colony, and attempted to enforce laws preventing such action. The settlers in the outlying district felt that they owed no allegiance to the laws of the colony in which they did not live, and refused to obey the company’s mandates. Then followed a long-drawn-out controversy between the settlers and the East India Company, which resembled in many respects the differences between England and her American colony.

It was during this period of oppression that the settlers of the Cape of Good Hope first exhibited the betokening signs of a nation. The communities of Hollanders, Germans, and French were constantly in such close communication with one another that each lost its distinguishing marks and adopted the new manners and customs which were their collective coinage. They suffered the same indignities at the hands of the East India Company, and naturally their sympathies drew them into a closer bond of fellowship, so that almost all national and racial differences were wiped out.

Never in the history of South Africa were all things so favourable for the establishment of a truly Afrikander nation and government. A leader was all that was necessary to throw off the yoke of continental control, but none was forthcoming.

At this propitious time the Napoleonic wars in Europe resulted so disastrously for France that she was compelled to cede to England the South African settlement, which had been acquired with the annexation of Holland, and the settlers believed their hour of deliverance from tyranny had arrived. They hailed the coming of the British forces with hopes for the improvement of their conditions, fondly believing that the British could treat them with no greater severity than that which they had suffered under the rule of the Dutch Company.

But their hopes were short-lived after the British garrison occupied Cape Town, and they soon learned that they had escaped from one kind of torment and oppression only to be burdened with another more harassing. The British administrators found a friendly people, eager to become British subjects, and, by exercise of undue authority, quickly transformed them into desperate enemies of British rule. The American colonies had but a short time before taught British colonial statesmen a dire lesson, but it was not applied to the South African colony, and the mistake has never been remedied.

Had the lesson learned in America been applied at that time, British rule would now be supreme in South Africa, and the two republics which are the eyesore of every Englishman in the country would probably never have come into existence. The British administrators ruled the colony as they had been taught in London, and allowed no local impediments to swerve them. The result of this method of government was that the Boer settlers, who had opinions of their own, became bitterly opposed to the British rule. The administrators attempted to coerce the Boers, and formulated laws which were meat to the newly arrived English immigrants and poison to the old settlers.

One of the indirect causes of the first Boer uprising against the British Government at the Cape was the slavery question. In the Transvaal there is a national holiday—March 6th—to commemorate the uprising of 1816, and it is known throughout the country as “Slagter’s Nek Day.” To the Boers it is a day of sad memory, and the recurrence of it does not soften their enmity of the English nation.

In October, 1815, a Boer farmer named Frederick Bezuidenhout was summoned to appear in a local court to answer a charge of maltreating a native. The Boer refused to obey the summons, and, with a sturdy native, awaited the arrival of the Government authorities in a cave near his home. A lieutenant named Rousseau and twenty soldiers found the Boer and the native in the cave, and demanded their surrender. Bezuidenhout refused to surrender, and he was almost instantly killed.

When the news of his death reached his friends they became greatly aroused, and, arming themselves, vowed to expel the English “tyrants” from the country. The English soldiers captured five of the leaders, and on March 6, 1816, hanged them on the same scaffold at Slagter’s Nek, a name afterward given to the locality because of the bungling work of the hangmen and the ghastly scenes presented when the scaffold fell to the ground, bearing with it the half-dead prisoners.

The story of this event in the Boer history is as familiar to the Dutch schoolboy as that of the Boston Tea-Party is to the American lad, and its repetition never fails to arouse a Boer audience to the highest degree of anger.

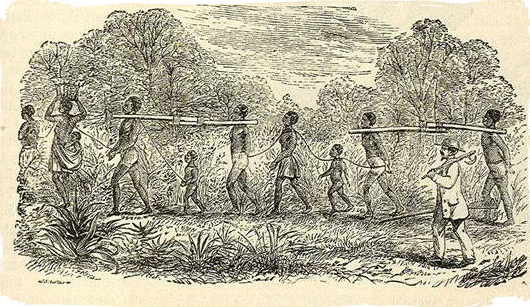

The primal cause of the departure of the Boers from Cape Colony, or the “Great Trek,” as it is popularly known, was the ill treatment which they received from the British administration in connection with the emancipation of their slaves and the depredations of hordes of thieving native tribes. The Boers had agreed about 1830 to emancipate all their slaves, and they had received from the British Government promises of ample compensation.

After the slaves had been freed, and the majority of the Boer farmers had become bankrupt by the proceeding, the Government offered less than half the promised compensation. The Boers naturally and indignantly refused to accept less than the amounts England had promised of her own free will. The Boers felt sorely aggrieved, but, being in the minority in the colony, could secure no redress. Several years after the slaves had been freed great hordes of thieving natives swept across the frontiers, and in several months inflicted these losses upon the farmers: 706 farmhouses partially or totally destroyed by fire; 60 farm wagons destroyed; 5,713 horses, 112,000 head of cattle, and 162,000 sheep stolen.

The value of the property destroyed and stolen by the blacks amounted to almost two million dollars. Much of the live stock was recovered by the Boer farmers, who had the boldness to pursue the robbers into their mountain fastnesses, but the Government did not allow them to hold even such cattle as they identified as having been driven away by the natives, but compelled them to yield all to the Government. When they asked for compensation for restoring the property to the Government, the Boers received such a promise from the governor, D’Urban; but Lord Glenelg, the British colonial secretary, vetoed the suggestion, and informed the Boers that their conduct in recovering the stolen property was outrageous and unworthy of English subjects.

Even Boer disposition, inured as it was to all kinds of unrighteousness, could not fail to take notice of this crowning insult. They consulted among themselves, and it was decided to leave the colony where they had suffered so many wrongs. Accordingly, in the spring of 1835 they sacrificed their farms at whatever prices they could secure for them, and announced to Lieutenant-Governor Stockenstrom their intention of departing to another section of the country.

To be certain that they would be free from British interference, the Boer leaders applied to the lieutenant-governor for his opinion on the subject, and he informed them that they were free to leave the colony, and that as soon as they stepped across the border England ceased to be their master. Later, Englishmen have sagely declared that the Boers having once been British subjects always remained such, whether they lived on British or Transvaal soil. The objects of the expedition were set forth in a document published in 1837 by Piet Retief, its leader. It reads, in part, as follows:

“We despair of saving the colony from those evils which threaten it by the turbulent and dishonest conduct of native vagrants who are allowed to infest the country in every part; nor do we see any prospect of peace or happiness for our children in a country thus distracted by internal commotions.

“We complain of the continual system of plunder which we have for years endured from the Kaffirs and other coloured classes, and particularly by the last invasion of the colony, which has desolated the frontier districts and ruined most of the inhabitants.

“We complain of the unjustifiable odium which has been cast upon us by interested and dishonest persons under the name of religion, whose testimony is believed in England, to the exclusion of all evidence in our favour, and we can foresee as a result of this prejudice nothing but the total ruin of the country.

“We are now leaving the fruitful land of our birth, in which we have suffered enormous losses and continual vexations, and are about to enter a strange and dangerous territory; but we go with a firm reliance on an all-seeing, just, and merciful God, whom we shall always fear and humbly endeavour to obey.”

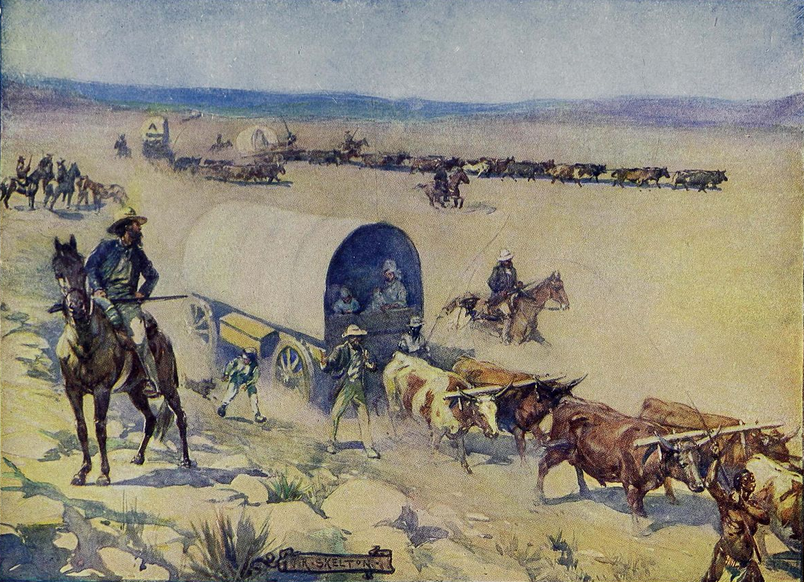

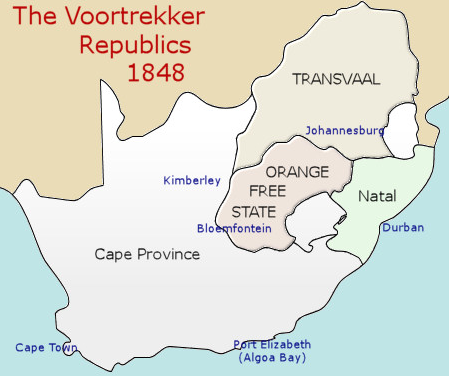

The first “trekking” party, or the “Voortrekkers,” consisted of about two hundred persons under the leadership of Andries Hendrik Potgieter. These crossed the Orange River and settled in that part of the country now known as the Orange Free State. This party had many battles with the natives, but succeeded in securing a level although not particularly arable stretch of land near Thaba’ntshu for settlement.

In August, 1836, after remaining a short time in the neighbourhood of Thaba’ntshu, a number of the settlers became dissatisfied with their location and “trekked” farther north toward the Vaal River, which is the present northern boundary of the Orange Free State. Before they had proceeded a great distance they were attacked by the Matabele natives under Chief Moselekatse, and fifty of their number were slain.

When the news of the slaughter reached the main body of the settlers a “laager,” or improvised fort, was formed by locking together the fifty big transport wagons that had been brought from Cape Colony. Behind these the men, women, and children fought side by side against the innumerable Matabeles, and after a desperate battle succeeded in defeating them. The natives captured and drove away about ten thousand head of cattle and sheep—almost the entire wealth of the settlers.

The settlement, however, increased rapidly in population, and, several years after the first Boers arrived there, application was made for English protection. It was granted to them, but was withdrawn again in 1854, when the British colonial secretary decided that England had more African land than was desirable. The Boers begged to be retained as an English colony, but in vain, and the fifteen thousand inhabitants were compelled to establish a government of their own, which is to-day embodied in that of the Orange Free State.

Since that memorable day in 1854, when the British flag was hauled down from the flagstaff at the Bloemfontein fort, both the British and the Boers have had revulsions of feeling. The British regret that their flag is absent from the fort, and the Boers will yield their lives before they ever allow it to be raised again.

The second expedition, and the one which comprised the founders of the South African Republic, departed from Cape Colony in the fall of 1835, with no fixed destination in view, but with a general idea to settle somewhere outside the realm of British influence. The “trekkers” were under the leadership of Piet Retief, a man of considerable wealth and executive ability, who determined to lead them across the untraveled Dragon Mountain, in the east of the colony.

In this party were three families of Krugers, and among them the present President of the South African Republic, then a boy of ten years. After many skirmishes with the natives, Retief and his followers reached Port Natal, the site of the present beautiful city of Durban, where they were welcomed by the members of the English settlement who had established themselves on the edge of Zululand as an independent organization. The handful of British immigrants were overjoyed to have this addition to the forces which were necessary to hold the natives in subjection, and they induced the majority of the Boers to settle in the vicinity of Port Natal.

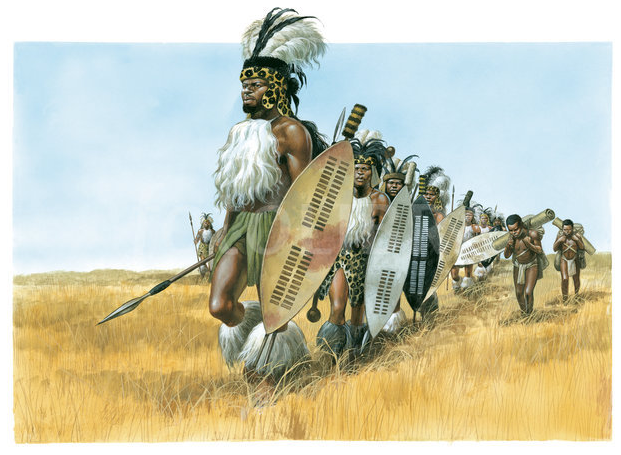

Retief and his leaders were pleased with the location and the richness of the soil, and finally determined to remain there if the native chiefs could be induced to enter into treaties transferring all rights to the soil. Dingaan, a warlike native, was the chief of the tribes surrounding Port Natal, and to him Retief applied for the grant of territory which was to be the future home of the several thousand “trekkers” who had by that time journeyed over Dragon Mountain. Retief and his party of seventy, and thirty native servants, reached Dingaan’s capital in January, 1838, and took with them as a peace-offering several hundred head of cattle which had been stolen from Dingaan by another tribe and recovered by Retief.

Dingaan treated the Boers with great courtesy, and profusely thanked them for recovering his stolen cattle. After several interviews he ceded to the Boers the large territory from the Tugela to the Umzimvubu River, from the Dragon Mountain to the sea. This territory included almost the entire colony of Natal, as now constituted, and was one of the richest parts of South Africa.

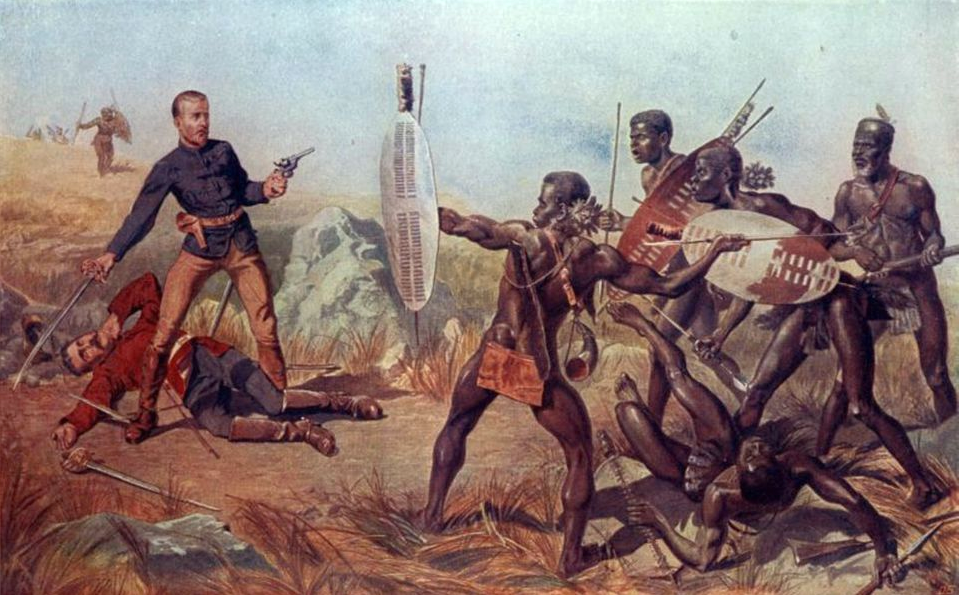

On February 4, 1838, when the treaty had been signed and the Boer leaders were being entertained by the chief in his hut, a typical massacre by the natives was enacted. At a signal from Dingaan, which is recorded as having been “Bulala abatagati” (“Slay the white devils!”), the Zulus sprang upon the unarmed Boers and massacred the seventy men with assegais and clubs before they could make the slightest resistance.

Frenzied by the sight of the white men’s blood, the Zulu chieftain gathered his hordes in warlike preparation, and determined to drive all the white settlers out of the country. A large “impi,” or war party, was despatched to attack and exterminate the remaining whites in their camps on the Tugela and Bushmans Rivers. These latter, while anxiously awaiting Retief’s return, were in no fear of hostilities, and the men for the most part were absent from their camps on hunting trips.

The “impi” swept down upon the camps by night, and murder of the foulest description prevailed. The Zulus spared none; men, women, and children, cattle, goats, sheep, and dogs—all fell under the ruthless assegais in the hands of the treacherous savages. In the confusion and darkness a few of the Boers escaped, among them having been the Pretorius and Rensburg families, which have since been high in the councils of the Boer nation. Fourteen men and boys took refuge on a hill now called Rensburg Kop, and held their assailants at bay while they improvised a “laager.”

When their ammunition was almost expended and their spirit exhausted, a white man on horseback was observed in the rear of the Zulu warriors. The hard-pressed emigrants signaled to him, and his ready mind, strained to the utmost tension, grasped the situation at a glance. He fearlessly turned his horse and rode to the abandoned wagons, almost a mile away, to secure some of the ammunition that had been left behind by the Boers when they were attacked by the Zulus. He loaded himself and his horse with powder and ball from the wagons, and with a courage that has never been surpassed rode headlong through the Zulu battle lines and bore to the beleaguered Boers the means of their subsequent salvation. That night the fearless rider assisted the fourteen Boers in routing the Zulus, and when morning dawned not a single living Zulu was to be seen.

The hero of that ride was Marthinus Oosthuyse, and his fame in South Africa rivals that of Paul Revere in American history. With the coming of the day the scattered emigrants congregated in a large “laager,” and for several days were engaged in beating off the attacks of the unsatiated Zulus. Wives, daughters, and sweethearts served the ammunition to the men, and with hatchets and clubs aided them in the uneven struggle.

After the Zulus’ spirit had been broken and they commenced to retreat, the gallant pioneers, their strength now increased by the addition of many stragglers, pursued their late assailants and killed hundreds of them. The town of Weenen, in Natal, takes its name from the weeping of the Boers for their dead. Rightly was it named, for no less than six hundred of the emigrants were massacred by the Zulus in the neighbourhood of the present site of the town.

While this massacre was in progress Dingaan and another part of his vast and well-trained army set out to wreak destruction upon the main body of the Boers which was still encamped upon the Dragon Mountain waiting for the return of Retief and his party. When the news of the massacre reached the main body, Pieter Uys and Potgieter hastened to re-enforce their distressed countrymen. They were not molested on the way, and had ample time to marshal all the Boer forces in the country and make preparations for vengeance upon the savages.

A force of three hundred and fifty men was raised, and this set out in the month of April, 1838, to attack Dingaan in his stronghold. The Zulu army was encountered near the King’s “Great Place.” The small army of Boers rode to within twenty yards of the van of the Zulus and then opened a steady and deadly fire. The savage weapons were no match for the poor yet superior firearms of the Boers, and in a short time Dingaan’s army was in full retreat. In pursuing them the Boers became separated and had great difficulty in fighting their way back to the main camp.

The story of how Pieter Uys was wounded by an assegai, and how his son, in endeavouring to save him, was pierced by a spear, is one of the noblest examples of heroism in the annals of South Africa. There were several more skirmishes with the Zulus, but the battle that broke the strength of the tribe was fought on December 16, 1838. There were but four hundred and sixty Boers in the army that attacked Dingaan’s army of twelve thousand, but the attack was so minutely planned and so admirably executed that the smaller force overwhelmed the greater and won the victory, which is annually observed on “Dingaan’s Day.”

The Boers lay fortified in a “laager,” and with unusual fortitude withstood the terrific onslaughts of the thousands of Zulus. Finally a cavalry charge of two hundred Boers created a panic in the Zulu army, and they retreated precipitously toward the Blood River, which was so named because its waters literally ran red with the life fluid of four hundred warriors who were shot on its banks or while attempting to ford it. On that day three thousand Zulus perished, and Dingaan made his ruin still more complete by burning his capital and hiding with his straggling army in the wilderness beyond the Tugela River.

After these grave experiences the Boer settlers believed themselves to be the rightful owners of the country which they had first sought to obtain by peaceful methods and afterward been compelled to take by sterner ones. But when they reached Port Natal they found that the British Government had taken possession of the country, and had issued a manifesto that the immigrant Boers were to be treated as a conquered race, and that their arms and ammunition should be confiscated.

To the Boers, who had just made the country valuable by clearing it of the Zulus, this high-handed action of the British Government had the appearance of persecution, and they naturally resented it, although they were almost powerless to oppose it by force of arms.

The Boer leader, Commandant-General Pretorius, who had been chosen by the first “Volksraad”—a governing body elected while the journey from Cape Colony to Natal was being made—led a number of his countrymen to the outskirts of Durban and formed a camp near that of the British garrison. He sent a message to Captain Smith, the commander of the British force of several hundred soldiers, and demanded the surrender of his position. In reply Smith led one hundred and fifty of his soldiers in a moonlight attack on the Boer forces and was completely routed.

The Boers then besieged Durban for twenty-six days and killed many of the English soldiers, but on the twenty-seventh day a schooner load of soldiers from Cape Colony augmented the forces of Captain Smith, and Pretorius was compelled to relinquish his efforts to secure control of the territory that his countrymen had a short time previously won from the Zulus.

Disheartened by their successive failures to secure a desirable part of the country wherein they might settle, the Boers again “trekked” northward over the Dragon Mountain. There they occupied the territory south of the Vaal River which had a short time previously been deserted by Potgieter and his party, who had journeyed northward with the intention of joining the Portuguese colony at Delagoa Bay, on the Indian Ocean.

These pilgrims were attacked by the deadly fever of the Portuguese country, and after remaining a short time in that region moved again and settled in different localities in the northern part of the territory now included in the South African Republic. Moselekatse and his Matabele warriors having been driven out of the country by the other “trekking” parties, the extensive region north of the Vaal River was then in undisputed possession of the Boers.

The farmers who left Cape Colony in 1835 and 1836 in different parties and after various vicissitudes settled across the Vaal were less than sixteen thousand in number, and were scattered over a large area of territory. The nature of the country and the enmity of the leaders of the parties prevented a close union among them, although a legislative assembly, called a “Volksraad,” was established after much disorder. The four principal “trekking” parties had sought four of the most fertile spots in the newly discovered territory, and established the villages of Utrecht, Lydenburg, Potchefstrom, and Zoutpansberg.

When the Volksraad was found to be inadequate to meet the requirements of the situation these villages were transformed into republics, each with a government independent of the others. The government of the limited areas of land occupied by the four republics was fairly successful, but the surrounding territory became a practical no-man’s-land, where roamed the worst criminals of the country and hundreds of detached bands of marauding natives.

The Boers imposed a labour tax upon all the natives who lived in the territory claimed by the four republics, and for a period of ten years the taxes were paid without a murmur. About that time, however, the native tribes had recovered from the great losses inflicted upon them by the emigrant farmers, and they were numerous enough to make an armed resistance to the demands of the governments. White women and children were massacred and property was destroyed at every opportunity.

For purposes of self-preservation the four republics decided to unite the governments under one head, and, after many disputes and disorders, succeeded, in May, 1864, in forming a single republic, with Marthinus Wessel Pretorius as President, and Paul Kruger as commandant-general of the army.

Ten months after the organization of the republic the Barampula tribe and a number of lawless Europeans rebelled against the authority of the Government, and Kruger was obliged to attempt their subjugation. Owing to a lack of ammunition and funds, he failed to end the rebellion, and as a result the Boers were compelled to withdraw from a large part of the territory they had occupied. Up to this time the Boers had not been interfered with by the Government of Cape Colony, but another tribal rebellion that followed the Barampula disturbance led to the establishment of a court of arbitration, in which the English governor of Natal figured as umpire.

The result of the arbitration was that the rebellious tribes were awarded their independence, and that a large part of the Boers’ territory was taken from them. The emigrant farmers who had settled the country maintained that President Pretorius was responsible for the loss of territory and compelled him to resign, after which the Rev. Thomas François Burgers, a shrewd but just clergyman-lawyer, was elected head of the republic. Burgers believed that the republic was destined to become a power of world-wide magnitude, and instantly used his position to attain that object. He went to Holland to secure money, immigrants, and teachers for the state schools. He secured half a million dollars with which to build a railroad from his seat of government to Delagoa Bay, and sent the railway material to Lourenzo Marques, where the rust is eating it today.

When Burgers returned to Pretoria, the capital of the republic, he found that Chief Secoceni, of the big Bapedi tribe, had defied the power of his Government, and was murdering the white immigrants in cold blood. Burgers led his army in person to punish Secoceni, and captured one of the native strong-holds, but was so badly defeated afterward that his soldiers became disheartened and decided to return to their homes.

Heavy war taxes were levied, and when the farmers were unable to pay them the Government was impotent to conduct its ordinary affairs, much less quell the rebellion of the natives. The Boers were divided among themselves on the subject of further procedure, and a civil war was imminent. The British Government, hearing of the condition of the republic’s affairs, sent Sir Theophilus Shepstone, who had held a minor office at Natal, to Pretoria with almost limitless powers. He called upon President Burgers and stated to him that his mission was to annex the country to England, and gave as his reasons for such a proceeding the excuse that the unsettled condition of the native races demanded it.

Burgers pointed out to Shepstone that the native races had not harmed the English colonies, and that a new constitution, modeled after that of America, with a standing police force of two hundred mounted men, would put an end to all the republic’s troubles with the natives. Shepstone, however, had the moral support of a small party of Boers who were dissatisfied with Burgers’ administration, and on April 12, 1877, declared the republic a possession of the British Empire. Burgers retired from the presidency under protest, and Shepstone established a form of government that for a short time proved acceptable to many of the Boers. He renamed the country Transvaal, and added a considerable military force.

But the Boers were not accustomed to foreign interference in their affairs, and twice sent deputations to England to have the government of the country returned to their own hands. Paul Kruger was a member of both deputations, which showed ample proof that the annexation was made without the consent of the majority of the Boers, but the English Colonial Office refused to withdraw the British flag from the Transvaal.

Sir Owen Lanyon, a man of no tact and an inordinate hater of the Boers, succeeded Shepstone as administrator of the Transvaal in 1879, and in a short time aroused the anger of his subjects to such an extent that an armed resistance to the British Government was decided upon. The open rebellion was delayed a short time by the election of Mr. Gladstone as Prime Minister of England, and, as he had publicly declared the righteousness of the Boer cause, the people of the Transvaal looked to him for their independence. When Mr. Gladstone refused to interfere in the Transvaal affairs the Boers held a meeting on the present site of Krugersdorp, and elected Paul Kruger, M. W. Pretorius, and Pieter J. Joubert a triumvirate to conduct the government.

At this meeting each Boer, holding a stone in his hand, took an oath before the Almighty that he would shed the last drop of blood, if need were, for his beloved country. The stones were cast into one great heap, over which a tall monument was erected several years afterward. The monument is annually made the rendezvous of large numbers of Boers, who there renew the solemn pledges to protect their country from aggressors.

On the national holiday, Dingaan’s Day, December 16, 1880, the four-colour flag of the republic was again raised at the temporary capital at Heidelberg. The triumvirate sent a manifesto to Sir Owen Lanyon explaining the causes of discontent, and ending with this significant sentence, which has ever remained a motto of the individual Boers:

“We declare before God, who knows the heart, and before the world, that the people of the South African Republic have never been subjects of Her Majesty, and never will be.”

Lanyon cursed the men who brought the manifesto to him, and straightway proceeded to execute the authority he possessed. His soldiers fired on a party of Boers proceeding toward Potchefstrom, where they intended to have the proclamation of independence printed. The Boers defeated the soldiers the same day the Transvaal flag was hoisted at Heidelberg, and the war, which had been impending for several months, was suddenly precipitated before either of the contestants was prepared.

Lanyon ordered the garrison of two hundred and sixty-four men at Leydenburg, under Colonel Anstruther, to proceed to Pretoria, the English capital. At Bronkhorst Spruit, Colonel Anstruther’s force was met by an equal number of Boers, who immediately attacked him. The engagement was brief but terrible, and the English forces were compelled to surrender.

Lanyon then sent to Natal for assistance, and Sir George Colley and a body of more than a thousand trained soldiers and volunteers set out to assist the English in the Transvaal, who for the most part were besieged in the different towns. Commandant-General Pieter Joubert, with a force of about fifteen hundred Boers, went forward into Natal for the purpose of meeting Colley, and occupied a narrow passage in the mountains known as Laing’s Nek. Colley attempted to force the pass on January 28, 1881, but the Boers inflicted such a heavy loss upon his forces that he was compelled to retreat to Mount Prospect and await the arrival of fresh troops from England.

Eleven days after the battle of Laing’s Nek, General Colley and three hundred men, while patrolling the road near the Ingogo River, were attacked by a body of Boers under Commandant Nicholaas Smit. The Boers killed and wounded two thirds of the English force engaged, and compelled the others to retreat in disorder. Up to this time the Boers had lost seventeen men killed and twenty-eight wounded, while the British loss was two hundred and fifty killed and three hundred and fifty wounded.

During the night of February 26th General Colley made a move which was responsible for one of the greatest displays of bravery the world has ever seen. The fight at Majuba Hill was won by the Boers against greater odds than have been encountered by any volunteer force in modern times, and is an example of the courage, bravery, and absolute confidence of the Boers when they believe they are divinely guided.

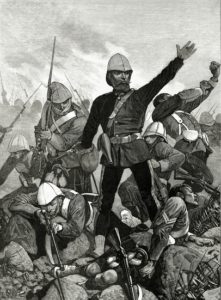

Between the camps of General Colley and Commandant-General Joubert lay Majuba Hill, a plateau with precipitous sides and a perfectly level top about twenty-five hundred feet above the camps. In point of resemblance the hill was a huge inverted tub whose summit could only be reached by a narrow path. General Colley and six hundred men, almost all of whom were trained soldiers fresh from England, ascended the narrow path by moonlight, and when the sun rose in the morning were able to look from the summit of the hill and see the Boer camp in the valley.

The plan of campaign was that the regiments that had been left behind in camp should attempt to force the pass through Laing’s Nek, and that the force on Majuba Hill should make a new attack on the Boers and in that manner crush the enemy in the pass. So positive were the soldiers of the success that awaited their plans that they looked down from their lofty position into the enemy’s lines and speculated on the number of Boers that would live to tell the story of the battle.

It was Sunday morning, and had the distance between the two armies been less, the soldiers on the hill might have heard the sound of many voices singing hymns of praise and the prayers that were being offered by the Boers kneeling in the valley. The English held their enemies in the palm of their hand, it seemed, and with a few heavy guns they could have killed them by the score. The sides of the hill were so steep that it did not enter the minds of the English that the Boers would attempt to ascend except by the same path which they had traversed, and that was impossible, because the path leading from the base was occupied by the remaining English forces.

The idea that the Boers would climb from terrace to terrace, from one bush to another, and gain the summit in that manner, occurred to no one. Before there was any stir in the Boers’ camp the English soldiers stood on the edge of the summit and, shaking their fists in exultation, challenged the enemy: “Come up here, you beggars!”

The Boers soon discovered the presence of the English on the hill, and the camp presented such an animated scene that the English soldiers were led to imagine that consternation had seized the Boers, and that they were preparing for a retreat.

A short time afterward, when the Boers marched toward the base of the hill, the illusion was dispelled; and still later, when one hundred and fifty volunteers from the Boer army commenced to ascend the sides of the hill, the former spirit of braggadocio which characterized the British soldier resolved itself into a feeling of nervousness. During the forenoon the British soldiers fired at such of the climbing Boers as they could see, but the Boers succeeded in dodging from one stone to another, so that only one of their number was killed in the ascent.

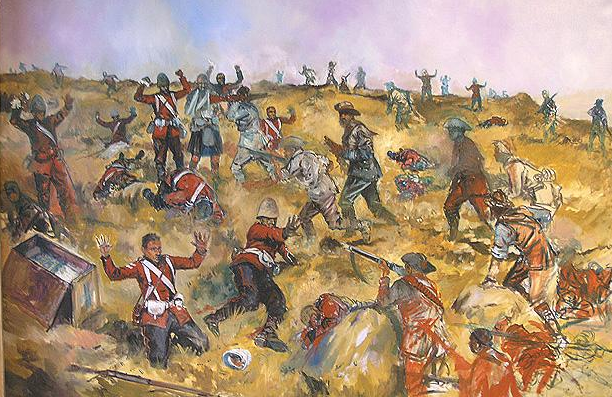

When the one hundred and fifty Boers reached the summit of the hill, after an arduous climb of more than five hours, they lay behind rocks at the edge and commenced a hot fire at the English soldiers, who had retreated into the centre of the plateau, thirty yards distant. The English soldiers had been ordered to fix their bayonets and were prepared to charge, but the order was never given. A fresh party of Boers had reached the summit and threatened to flank the English, who, having lost many of their officers and scores of men, became wildly panic-stricken.

Several minutes after General Colley was killed, the British soldiers who had escaped from the storm of bullets broke for the edge of the summit and allowed themselves to drop and roll down the sides of the hill. When the list of casualties was completed it was found that the Boers had killed ninety-two, wounded one hundred and thirty-four, and taken prisoners fifty-nine soldiers of the six hundred who ascended the hill. The loss on the Boers’ side was one killed and five wounded.

A short time after the fight at Majuba Hill an armistice was arranged between Sir Evelyn Wood, the successor of General Colley, and the Triumvirate, and this led to the partial restoration of the independence of the South African Republic. By the terms of peace concluded between the two Governments, the suzerainty of Great Britain was imposed as one of the conditions, but this was afterward modified so that the Transvaal became absolutely independent in everything relating to its internal affairs. Great Britain, however, retained the right to veto treaties which the Transvaal Government might make with foreign countries.

[…] Source link […]

4.5

Very interesting history.

P.G.Martel has a stash of old history books, and they tend to give a more honest perspective than the majority of modern works. As we work to save Western Culture, it is important to have an accurate accounting of our history. Glad you enjoyed it.

Thank you! This is an excellent & very interesting picture of Boer History. Added to my StateRepression category.

Any work done on the History of Rhodesia?

Good question. I will have to let P.G. respond to that. I know a couple of guys who fought over there in the 70s, but do not have any real info beyond their anecdotes.

I may put up something about the life of Cecil Rhodes in the near future. But I will also keep an eye out for good material on Rhodesia. Thanks for the suggestion.