Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Christmas: Its Origins and Associations, by W. F. Dawson (published 1902).

The Angels’ Song has been called the first Christmas Carol, and the shepherds who heard this heavenly song of peace and goodwill, and went “with haste” to the birthplace at Bethlehem, where they “found Mary, and Joseph, and the Babe lying in a manger,” certainly took part in the first celebration of the Nativity. And the Wise Men, who came afterwards with presents from the East, being led to Bethlehem by the appearance of the miraculous star, may also be regarded as taking part in the first celebration of the Nativity, for the name Epiphany (now used to commemorate the manifestation of the Saviour) did not come into use till long afterwards, and when it was first adopted among the Oriental Churches it was designed to commemorate both the birth and baptism of Jesus, which two events the Eastern Churches believed to have occurred on January 6th. Whether the shepherds commemorated the Feast of the Nativity annually does not appear from the records of the Evangelists; but it is by no means improbable that to the end of their lives they would annually celebrate the most wonderful event which they had witnessed.

Within thirty years after the death of our Lord, there were churches in Jerusalem, Cæsarea, Rome, and the Syrian Antioch. In reference to the latter, Bishop Ken beautifully says:—

“Fair Antioch the rich, the great,

Of learning the imperial seat,

You readily inclined,

To light which on you shined;

It soon shot up to a meridian flame,

You first baptized it with a Christian name.”

Clement, one of the Apostolic Fathers and third Bishop of Rome, who flourished in the first century, says: “Brethren, keep diligently feast-days, and truly in the first place the day of Christ’s birth.” And according to another of the early Bishops of Rome, it was ordained early in the second century, “that in the holy night of the Nativity of our Lord and Saviour, they do celebrate public church services and in them solemnly sing the Angels’ Hymn, because also the same night He was declared unto the shepherds by an angel, as the truth itself doth witness.”

But, before proceeding further with the historical narrative, it will be well now to make more particular reference to the fixing of the date of the festival.

Fixing the Date of Christmas

Whether the 25th of December, which is now observed as Christmas Day, correctly fixes the period of the year when Christ was born is still doubtful, although it is a question upon which there has been much controversy. From Clement of Alexandria it appears, that when the first efforts were made to fix the season of the Advent, there were advocates for the 20th of May, and for the 20th or 21st of April. It is also found that some communities of Christians celebrated the festival on the 1st or 6th of January; others on the 29th of March, the time of the Jewish Passover: while others observed it on the 29th of September, or Feast of Tabernacles. The Oriental Christians generally were of opinion that both the birth and baptism of Christ took place on the 6th of January. Julius I, Bishop of Rome (A.D. 337-352), contended that the 25th of December was the date of Christ’s birth, a view to which the majority of the Eastern Church ultimately came round, while the Church of the West adopted from their brethren in the East the view that the baptism was on the 6th of January. It is, at any rate, certain that after St. Chrysostom Christmas was observed on the 25th of December in East and West alike, except in the Armenian Church, which still remains faithful to January 6th. St. Chrysostom, who died in the beginning of the fifth century, informs us, in one of his Epistles, that Julius, on the solicitation of St. Cyril of Jerusalem, caused strict inquiries to be made on the subject, and thereafter, following what seemed to be the best authenticated tradition, settled authoritatively the 25th of December as the anniversary of Christ’s birth, the Festorum omnium metropolis, as it is styled by Chrysostom. It may be observed, however, that some have represented this fixing of the day to have been accomplished by St. Telesphorus, who was Bishop of Rome A.D. 127-139, but the authority for the assertion is very doubtful. There is good ground for maintaining that Easter and its accessory celebrations mark with tolerable accuracy the anniversaries of the Passion and Resurrection of our Lord, because we know that the events themselves took place at the period of the Jewish Passover; but no such precision of date can be adduced as regards Christmas. Dr. Geikie says: “The season at which Christ was born is inferred from the fact that He was six months younger than John, respecting the date of whose birth we have the help of knowing the time of the annunciation during his father’s ministrations in Jerusalem. Still, the whole subject is very uncertain. Ewald appears to fix the date of the birth as five years earlier than our era. Petavius and Usher fix it as on the 25th of December, five years before our era; Bengel, on the 25th of December, four years before our era; Anger and Winer, four years before our era, in the spring; Scaliger, three years before our era, in October; St. Jerome, three years before our era, on December 25th; Eusebius, two years before our era, on January 6th; and Ideler, seven years before our era, in December.” Milton, following the immemorial tradition of the Church, says that—

“It was the winter wild.”

But there are still many who think that the 25th of December does not correspond with the actual date of the birth of Christ, and regard the incident of the flocks and shepherds in the open field, recorded by St. Luke, as indicative of spring rather than winter. This incident, it is thought, could not have taken place in the inclement month of December, and it has been conjectured, with some probability, that the 25th of December was chosen in order to substitute the purified joy of a Christian festival for the license of the Bacchanalia and Saturnalia which were kept at that season. It is most probable that the Advent took place between December, 749, of Rome, and February, 750.

Dionysius Exiguus, surnamed the Little, a Romish monk of the sixth century, a Scythian by birth, and who died a.d. 556, fixed the birth of Christ in the year of Rome 753, but the best authorities are now agreed that 753 was not the year in which the Saviour of mankind was born. The Nativity is now placed, not as might have been expected, in a.d. 1, but in b.c. 5 or 4. The mode of reckoning by the “year of our Lord” was first introduced by Dionysius, in his “Cyclus Paschalis,” a treatise on the computation of Easter, in the first half of the sixth century. Up to that time the received computation of events through the western portion of Christendom had been from the supposed foundation of Rome (b.c. 754), and events were marked accordingly as happening in this or that year, Anno Urbis Conditæ, or by the initial letters A.U.C. In the East some historians continued to reckon from the era of Seleucidæ, which dated from the accession of Seleucus Nicator to the monarchy of Syria, in b.c. 312. The new computation was received by Christendom in the sixth century, and adopted without adequate inquiry, till the sixteenth century. A more careful examination of the data presented by the Gospel history, and, in particular, by the fact that “Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judæa” before the death of Herod, showed that Dionysius had made a mistake of four years, or perhaps more, in his calculations. The death of Herod took place in the year of Rome a.u.c. 750, just before the Passover. This year coincided with what in our common chronology would be b.c. 4—so that we have to recognise the fact that our own reckoning is erroneous, and to fix b.c. 5 or 4 as the date of the Nativity.

Now, out of the consideration of the time at which the Christmas festival is fixed, naturally arises another question, viz.:—

The Connection of Christmas with Ancient Festivals

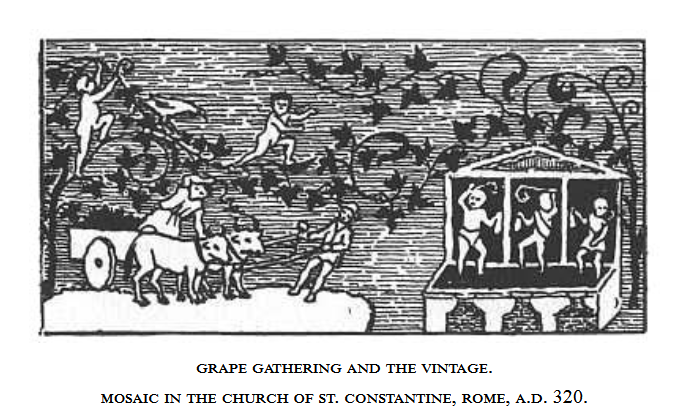

Sir Isaac Newton says the Feast of the Nativity, and most of the other ecclesiastical anniversaries, were originally fixed at cardinal points of the year, without any reference to the dates of the incidents which they commemorated, dates which, by lapse of time, it was impossible to ascertain. Thus the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary was placed on the 25th of March, or about the time of the vernal equinox; the Feast of St. Michael on the 29th of September, or near the autumnal equinox; and the Birth of Christ at the time of the winter solstice. Christmas was thus fixed at the time of the year when the most celebrated festivals of the ancients were held in honour of the return of the sun which at the winter solstice begins gradually to regain power and to ascend apparently in the horizon. Previously to this (says William Sandys, F.S.A.), the year was drawing to a close, and the world was typically considered to be in the same state. The promised restoration of light and commencement of a new era were therefore hailed with rejoicings and thanksgivings. The Saxon and other northern nations kept a festival at this time of the year in honour of Thor, in which they mingled feasting, drinking, and dancing with sacrifices and religious rites. It was called Yule, or Jule, a term of which the derivation has caused dispute amongst antiquaries; some considering it to mean a festival, and others stating that Iol, or Iul (spelt in various ways), is a primitive word, conveying the idea of Revolution or Wheel, and applicable therefore to the return of the sun. The Bacchanalia and Saturnalia of the Romans had apparently the same object as the Yuletide, or feast of the Northern nations, and were probably adopted from some more ancient nations, as the Greeks, Mexicans, Persians, Chinese, &c., had all something similar. In the course of them, as is well known, masters and slaves were supposed to be on an equality; indeed, the former waited on the latter. Presents were mutually given and received, as Christmas presents in these days. Towards the end of the feast, when the sun was on its return, and the world was considered to be renovated, a king or ruler was chosen, with considerable power granted to him during his ephemeral reign, whence may have sprung some of the Twelfth-Night revels, mingled with those in honour of the Manifestation and Adoration of the Magi. And, in all probability, some other Christmas customs are adopted from the festivals of the ancients, as decking with evergreens and mistletoe (relics of Druidism) and the wassail bowl. It is not surprising, therefore, that Bacchanalian illustrations have been found among the decorations in the early Christian Churches. The illustration on the following page is from a mosaic in the Church of St. Constantine, Rome, A.D. 320.

Dr. Cassel, of Germany, an erudite Jewish convert who is little known in this country has endeavoured to show that the festival of Christmas has a Judæan origin. He considers that its customs are significantly in accordance with those of the Jewish festival of the Dedication of the Temple. This feast was held in the winter time, on the 25th of Cisleu (December 20th), having been founded by Judas Maccabæus in honour of the cleansing of the Temple in b.c. 164, six years and a half after its profanation by Antiochus Epiphanes. In connection with Dr. Cassel’s theory it may be remarked that the German word Weihnachten (from weihen, “to consecrate, inaugurate,” and nacht, “night”) leads directly to the meaning, “Night of the Dedication.”

In proceeding with our historical survey, then, we must recollect that in the festivities of Christmastide there is a mingling of the Divine with the human elements of society—the establishment and development of a Christian festival on pagan soil and in the midst of superstitious surroundings. Unless this be borne in mind it is impossible to understand some customs connected with the celebration of Christmas. For while the festival commemorates the Nativity of Christ, it also illustrates the ancient practices of the various peoples who have taken part in the commemoration, and not inappropriately so, as the event commemorated is also linked to the past. “Christmas” (says Dean Stanley) “brings before us the relations of the Christian religion to the religions which went before; for the birth at Bethlehem was itself a link with the past. The coming of Jesus Christ was not unheralded or unforeseen. Even in the heathen world there had been anticipations of an event of a character not unlike this. In Plato’s Dialogue bright ideals had been drawn of the just man; in Virgil’s Eclogues there had been a vision of a new and peaceful order of things. But it was in the Jewish nation that these anticipations were most distinct. That wonderful people in all its history had looked, not backward, but forward. The appearance of Jesus Christ was not merely the accomplishment of certain predictions; it was the fulfilment of this wide and deep expectation of a whole people, and that people the most remarkable in the ancient world.” Thus Dean Stanley links Christianity with the older religions of the world, as other writers have connected the festival of Christmas with the festivals of paganism and Judaism. The first Christians were exposed to the dissolute habits and idolatrous practices of heathenism, as well as the superstitious ceremonials of Judaism, and it is in these influences that we must seek the true origin of many of the usages and institutions of Christianity. The old hall of Roman justice and exchange—an edifice expressive of the popular life of Greece and Rome—was not deemed too secular to be used as the first Christian place of worship: pagan statues were preserved as objects of adoration, being changed but in name; names describing the functions of Church officers were copied from the civil vocabulary of the time; the ceremonies of Christian worship were accommodated as far as possible to those of the heathen, that new converts might not be much startled at the change, and at the Christmas festival Christians indulged in revels closely resembling those of the Saturnalia.

Christmas in Times of Persecution

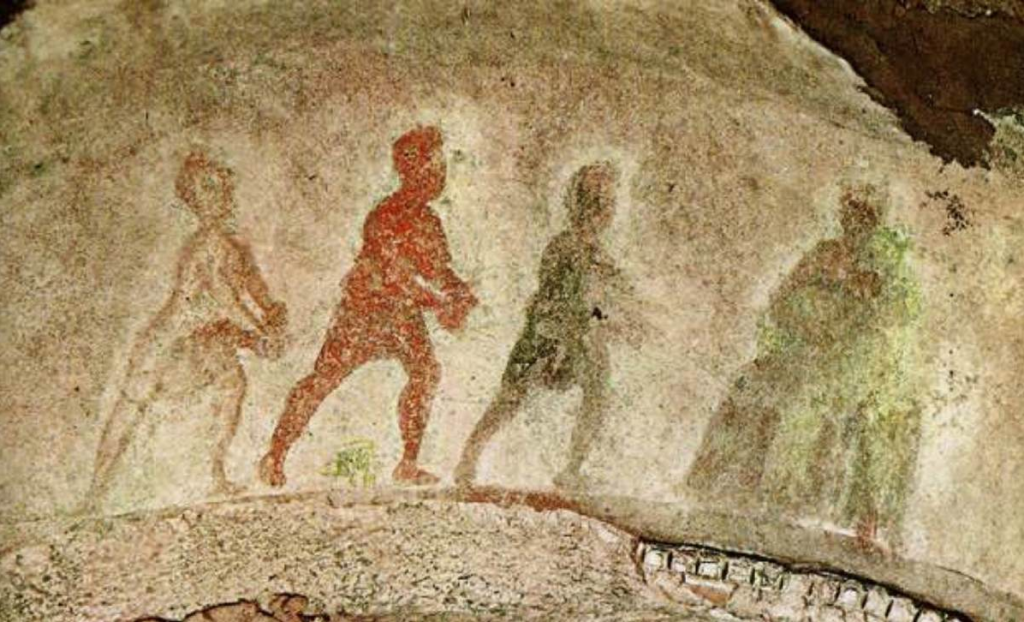

It is known that the Feast of the Nativity was observed as early as the first century, and that it was kept by the primitive Christians even in dark days of persecution. “They wandered in deserts, and in mountains, and in dens and caves of the earth” (Heb. xi. 38). Yet they were faithful to Christ, and the Catacombs of Rome contain evidence that they celebrated the Nativity.

The opening up of these Catacombs has brought to light many most interesting relics of primitive Christianity. In these Christian cemeteries and places of worship there are signs not only of the deep emotion and hope with which they buried their dead, but also of their simple forms of worship and the festive joy with which they commemorated the Nativity of Christ. On the rock-hewn tombs these primitive Christians wrote the thoughts that were most consoling to themselves, or painted on the walls the figures which gave them the most pleasure. The subjects of these paintings are for the most part taken from the Bible, and the one which illustrates the earliest and most universal of these pictures, and exhibits their Christmas joy, is “The Adoration of the Magi.” Another of these emblems of joyous festivity which is frequently seen, is a vine, with its branches and purple clusters spreading in every direction, reminding us that in Eastern countries the vintage is the great holiday of the year. In the Jewish Church there was no festival so joyous as the Feast of Tabernacles, when they gathered the fruit of the vineyard, and in some of the earlier celebrations of the Nativity these festivities were closely copied. And as all down the ages pagan elements have mingled in the festivities of Christmas, so in the Catacombs they are not absent. There is Orpheus playing on his harp to the beasts; Bacchus as the god of the vintage; Psyche, the butterfly of the soul; the Jordan as the god of the rivers. The classical and the Christian, the Hebrew and the Hellenic elements had not yet parted; and the unearthing of these pictures after the lapse of centuries affords another interesting clue to the origin of some of the customs of Christmastide. It is astonishing how many of the Catacomb decorations are taken from heathen sources and copied from heathen paintings; yet we need not wonder when we reflect that the vine was used by the early Christians as an emblem of gladness, and it was scarcely possible for them to celebrate the Feast of the Nativity—a festival of glad tidings—without some sort of Bacchanalia. Thus it appears that even beneath the palaces and temples of pagan Rome the birth of Christ was celebrated, this early undermining of paganism by Christianity being, as it were, the germ of the final victory, and the secret praise, which came like muffled music from the Catacombs in honour of the Nativity, the prelude to the triumph-song in which they shall unite who receive from Christ the unwithering crown.

But they who would wear the crown must first bear the cross, and these early Christians had to pass through dreadful days of persecution. Some of them were made food for the torches of the atrocious Nero, others were thrown into the Imperial fish-ponds to fatten lampreys for the Bacchanalian banquets, and many were mangled to death by savage beasts, or still more savage men, to make sport for thousands of pitiless sightseers, while not a single thumb was turned to make the sign of mercy. But perhaps the most gigantic and horrible of all Christmas atrocities were those perpetrated by the tyrant Diocletian, who became Emperor a.d. 284. The early years of his reign were characterised by some sort of religious toleration, but when his persecutions began many endured martyrdom, and the storm of his fury burst on the Christians in the year 303. A multitude of Christians of all ages had assembled to commemorate the Nativity in the temple at Nicomedia, in Bithynia, when the tyrant Emperor had the town surrounded by soldiers and set on fire, and about twenty thousand persons perished. The persecutions were carried on throughout the Roman Empire, and the death-roll included some British martyrs, Britain being at that time a Roman province. St. Alban, who was put to death at Verulam in Diocletian’s reign, is said to have been the first Christian martyr in Britain. On the retirement of Diocletian, satiated with slaughter and wearied with wickedness, Galerius continued the persecutions for a while. But the time of deliverance was at hand, for the martyrs had made more converts in their deaths than in their lives. It was vainly hoped that Christianity would be destroyed, but in the succeeding reign of Constantine it became the religion of the empire. Not one of the martyrs had died in vain or passed through death unrecorded.

“There is a record traced on high,

That shall endure eternally;

The angel standing by God’s throne

Treasures there each word and groan;

And not the martyr’s speech alone,

But every word is there depicted,

With every circumstance of pain

The crimson stream, the gash inflicted—

And not a drop is shed in vain.”

Celebrations under Constantine the Great

With the accession of Constantine (born at York, February 27, 274, son of the sub-Emperor Constantius by a British mother, the “fair Helena of York,” and who, on the death of his father at York in 306, was in Britain proclaimed Emperor of the Roman Empire) brighter days came to the Christians, for his first act was one of favour to them. He had been present at the promulgation of Diocletian’s edict of the last and fiercest of the persecutions against the Christians, in 303, at Nicomedia, soon after which the imperial palace was struck by lightning, and the conjunction of the events seems to have deeply impressed him. No sooner had he ascended the throne than his good feeling towards the Christians took the active form of an edict of toleration, and subsequently he accepted Christianity, and his example was followed by the greater part of his family. And now the Christians, who had formerly hidden away in the darkness of the Catacombs and encouraged one another with “Alleluias,” which served as a sort of invitatory or mutual call to each other to praise the Lord, might come forth into the Imperial sunshine and hold their services in basilicas or public halls, the roofs of which (Jerome tells us) “re-echoed with their cries of Alleluia,” while Ambrose says the sound of their psalms as they sang in celebration of the Nativity “was like the surging of the sea in great waves of sound.” And the Catacombs contain confirmatory evidence of the joy with which relatives of the Emperor participated in Christian festivities. In the tomb of Constantia, the sister of the Emperor Constantine, the only decorations are children gathering the vintage, plucking the grapes, carrying baskets of grapes on their heads, dancing on the grapes to press out the wine. This primitive conception of the Founder of Christianity shows the faith of these early Christians to have been of a joyous and festive character, and the Graduals for Christmas Eve and Christmas morning, the beautiful Kyrie Eleisons (which in later times passed into carols), and the other festival music which has come down to us through that wonderful compilation of Christian song, Gregory’s Antiphonary, show that Christmas stood out prominently in the celebrations of the now established Church, for the Emperor Constantine had transferred the seat of government to Constantinople, and Christianity was formally recognised as the established religion.

Episcopal References to Christmas and Cautions Against Excesses

Cyprian, the intrepid Bishop of Carthage, whose stormy episcopate closed with the crown of martyrdom in the latter half of the third century, began his treatise on the Nativity thus: “The much wished-for and long expected Nativity of Christ is come, the famous solemnity is come”—expressions which indicate the desire with which the Church looked forward to the festival, and the fame which its celebrations had acquired in the popular mind. And in later times, after the fulness of festivity at Christmas had resulted in some excesses, Bishop Gregory Nazianzen (who died in 389), fearing the spiritual thanksgiving was in danger of being subordinated to the temporal rejoicing, cautioned all Christians “against feasting to excess, dancing, and crowning the doors (practices derived from the heathens); urging the celebration of the festival after an heavenly and not an earthly manner.”

In the Council, generally called Concilium Africanum, held A.D. 408, “stage-playes and spectacles are forbidden on the Lord’s-day, Christmas-day, and other solemn Christian festivalls.” Theodosius the younger, in his laws de Spectaculis, in 425, forbade shows or games on the Nativity, and some other feasts. And in the Council of Auxerre, in Burgundy, in 578, disguisings are again forbidden, and at another Council, in 614, it was found necessary to repeat the prohibitory canons in stronger terms, declaring it to be unlawful to make any indecent plays upon the Kalends of January, according to the profane practices of the pagans. But it is also recorded that the more devout Christians in these early times celebrated the festival without indulging in the forbidden excesses.

Another great find! Nice.