Editor’s note: The following comprises the fourth chapter of Defenders of the Faith: The Christian Apologists of the Second and Third Centuries, by the Rev. Frederick Watson. M.A. (published 1879).

CHAPTER IV

The Defence

Three kinds of charges were brought against the Christians by the heathen — Moral, Theological, and Political. It was said they lived immoral lives; that they had no religion, or a bad one, or at least an illegal one; that they were traitors to the Emperor, and enemies of the public good. The first two excited the popular hatred, and were the causes of the tumultuous risings; the last furnished the subject-matter of the legal charge when they were brought before the courts.

The charge of Immorality seems, at first, to have been the most prominent: it sprung, no doubt, from the suspicious jealousy with which the secret meetings of the Christians were viewed. The persecutions rendered it necessary that the Christian worship should be conducted in secret and by night. Before the light, as Pliny tells us, the Christians met together in prayer to Christ. The heathen husband, whilst it was yet dark, missed his wife from his side, and vaguely suspected evil. Arguing from the heathen rites, it was thought that the Christian mysteries must be impure. Rumour soon gave shape to vague suspicion. “About the modest supper-room of the Christians,” says Tertullian, “a great ado is made.”

The ceremony of initiation into the society, it was said, was an abominable crime. The neophyte was caused to stab unawares an infant to death, and then all, in greedy haste, tore it limb from limb and devoured it. The feasting was carried to excess. At a given signal the light was put out and all indulged in promiscuous lust. Origen tells us the Jews were the authors of these charges — a thing likely enough in itself; but whether this was so or not, it is easy to see the foundation in fact for the calumny. The heathen had heard of the Eucharistic food of the Body and Blood of Christ, and of the love-feasts. To the first they would be incapable of giving a spiritual significance; the second had but one meaning to an impure imagination; love and lust were, alas! to the heathen of the day, almost interchangeable terms. Religious ceremonies and gross immoralities were closely connected in his experience. Purity was so rare that he disbelieved in its existence. Outward self-restraint was, in his idea, only a cloak to secret immorality: hence he distorted the love-feasts into licentious orgies, and the feeding on the Body and Blood of Christ into murdering and devouring an infant.

For these charges, Tertullian assures us, the heathen had lying rumour as their only witness; and yet the secret of the Christian meetings was by no means well kept. He says, “We are daily beset by foes, we are daily betrayed; we are ofttimes surprised in our meetings and congregations. And yet,” he asks, “who has ever happened on an infant wailing? Who has found any trace of uncleanness in his wife? Where is the man who, when he had discovered such atrocities, concealed them, or, whilst dragging the guilty before the judge, was bribed to silence?” As a matter of fact, the authorities from time to time did their best to procure evidence, and failed. Pliny investigated the nature of the Christian society in a thorough manner. He had no liking for it, quite the reverse; it was, in his eyes, “an absurd and immoderate superstition.” The Christians were possessed with “infatuation”; they were filled with “a contumacious and inflexible obstinacy.” But this is the worst he has to say. He searched, but could not find any basis for a criminal charge. He questioned apostates, and they were quite willing, for their own safety, to revile the name of Christ; but even they did not venture to blacken the fair fame of the Christians. Their evidence went no further than this, that the Christians were wont to assemble together before day, for prayer to Christ; for binding all together, by a solemn sacrament, to abstain from all kinds of sin; and for eating a harmless meal. Two deaconesses fell into Pliny’s hands, and he put them to the torture, but he could get nothing out of them to his purpose. The conclusion he comes to is this: the Christians are superstitious, they are obstinate, they will not obey the laws, but they are not criminal. In fact, Pliny’s report to Trajan might be summed up in the words, “I can find no occasion against these men, except I find it against them concerning the law of their God.”

Pliny’s investigation was made at the beginning of the second century, in Bithynia. About fifty years afterwards a violent persecution broke out in Gaul. Reports of the vile doings of the Christians had been circulated amongst the common people until they were goaded to madness. Vettius Epagathus, a young man of blameless life, was refused a hearing when he undertook to show, on behalf of his brethren, that nothing impious was done amongst them. Was he a Christian, the governor asked? He was. That was sufficient; his mouth was stopped, and he was numbered amongst the martyrs.

The heathen slaves of Christian martyrs were apprehended; they saw their masters suffering, and, in fear for themselves, falsely accused them of unnatural crimes. Then, as our account runs, “When the rumour of these accusations was spread abroad, all raged against us like wild beasts; so that if any formerly were temperate in their conduct to us on account of relationship, they then became exceedingly indignant and exasperated against us. And thus was fulfilled that which was spoken by our Lord: ” The time shall come when every one who slayeth you shall think that he offereth service to God.”

The threat of torture had been sufficient to cause the heathen slaves to accuse their masters. Its application was not sufficient to extort a confession from the Christians themselves; and yet, we are told, they suffered pains beyond description, Satan striving eagerly that some of the evil reports might be acknowledged by them.

Sanctus, a deacon, nobly endured all the sufferings that man could devise, and had but one word on his lips, “I am a Christian.” His body, with wounds, lost human shape, but in him Christ wrought great wonders; showing to the rest that there is nothing fearful where there is the Father’s love, and nothing painful where there is Christ’s glory.

For Blandina, a weak slave, all — even her Christian mistress — feared; but she baffled her tormentors though they did their worst, and in the midst of all her sufferings she found strength, and refreshment, and insensibility to pain, in saying, “I am a Christian, and there is no evil done amongst us.”

One more faithful witness — the most faithful of all. All had not stood firm; some had by their conduct caused evil reports and were sons of perdition, but others were won back again by the martyrs’ prayers. One of these latter was Biblias. “The devil,” such is the account, “thinking he had already swallowed her, and wishing to damn her still more by making her accuse (the brethren) falsely, brought her forth to punishment, and employed force to constrain her, already feeble and spiritless, to utter accusations of atheism against us. But she, in the midst of the tortures, came again to a sound state of mind, and awoke, as it were, out of a deep sleep, for the temporary punishment reminded her of the eternal punishment in hell; and she contradicted the accusers of Christians, saying, ‘How can children be eaten by those who do not think it lawful to partake even of the blood of brute beasts?’ And after this she confessed herself a Christian, and was added to the number of martyrs.”

And so the devil’s craft, as we see, betrayed him; and Christ rescued from his jaws one that was ready to go down into the pit; and the Christians gained a testimony not to be gainsayed. The deacon’s testimony was strong, the slave’s still stronger, but the testimony of her who had fallen was strongest of all. What could have raised the fallen one but the power of Christ working in her mightily? The witness extorted by suffering must have been for once the witness of truth.

It is interesting to learn that God honoured His martyrs in the eyes of men. Those who stood firm suffered as Christians, and were not ashamed. Those who apostatized suffered as murderers and profligates, and were tormented by their guilty conscience. The one came forth to their execution like “brides going to their bridal”; the others were downcast, and humbled, and weighed down with every kind of disgrace.

The Apologists pointed to such scenes as these, and asked, Is it possible that men who die as you see they do, can live as you say they do? In truth, the deaths of the Christians were a convincing testimony to the purity of their Christian lives. A life of self-indulgence is not a preparation for a martyr’s death. But those who were ever crucifying the flesh with its affections and lusts after a spiritual manner, were the men likely in the moment of trial to endure bravely the most dreadful suffering. One of the Apologists, Justin Martyr, saw the force of this argument, whilst still a heathen. He tells us, that when he “was delighting in the doctrines of Plato, and heard the Christians slandered, and saw them fearless of death and of all other things which are counted to be fearful, he perceived it was impossible that they could be living in wickedness and pleasure. For what sensual or intemperate man, or who that counts it good to feast on human flesh, could welcome death, that he might be deprived of his enjoyments, and would not rather continue always the present life?”

The Apologists appeal not only to Christian deaths but to Christian lives in defending themselves against this charge. They were able to point to the change which Christianity had effected in the lives of many. Tertullian says that the remarks used to be made, “What a woman she was! how wanton, how gay! What a youth he was! how profligate, how lustful! They have become Christians! So the hated name is given to a reformation of character.” And then he tells us further, that the heathen hated Christianity more than they loved goodness. The chaste Christian wife, and the obedient Christian son, and the faithful Christian servant, fared worse after their reformation than beforetime in their wickedness. The prisons were often full of Christians, but their Christianity was their only crime. Christian names were not to be found in the list of criminals. “It is always,” the same writer says in another place, “with your folk the prison is teeming, the mines are sighing, the wild beasts are fed; it is from you the exhibiters of gladiatorial shows always get their herd of criminals to feed up for the occasion. You find no Christian there, except simply as being such; or if one be there in any other capacity, a Christian he is no longer.”

Tertullian shows also how it is the Christians were so free from crime. Their morality was based on their religion; their moral sense had been educated by a Divine Teacher; their moral code had been taught them by Divine lips; and they expected to be judged by a Divine Judge. Eternal punishment, they believed, was due for sin; eternal life was the reward of goodness. Moreover, the commandment which had been laid upon them was exceeding wide; it reached even to the words of the lips and the thoughts of the heart. So far from injuring another, they patiently suffered injury themselves; so far from killing another, they were forbidden even to be angry. A Christian could not, like a philosopher, teach one thing and do another. He could not promulgate a code of morals, and not live up to it. Unless he were a Christian indeed, he ceased forthwith to be a Christian in name.

Perhaps this charge could hardly have been so widely believed without some basis of truth, and there is good reason for thinking that some of the heretics brought discredit on the Christian name. The Gnostics taught that matter, i.e. the stuff of which the world generally, and so the human body, was composed, was the principle of evil; and the question with them was, how to keep their higher nature uncorrupted by contact with it. One of their two theories was, “Do absolutely as you please; follow your own impulses; don’t give the subject a thought, it is not worth the trouble. Nothing your body can do can have any influence upon your spirit.” With such a theory we are prepared to hear that the Gnostics led a licentious life. Irenaeus tells us, “that they had been sent by Satan to bring dishonour upon the Church; so that men hearing what they say, may turn away from the preaching of the truth; and seeing what they practise, may speak evil of us all, who in fact have no fellowship with them, either in doctrine, or in morals, or in daily life.” Eusebius distinctly traces the “impious and absurd suspicions” against the Christians to the Gnostic theory and practice. They taught, he tells us, “that the basest deeds should be perpetrated by those that would arrive at perfection in the mysteries”; and the consequence was, “to the unbelieving Gentiles they offered scope to slander the truth of God, as the report proceeding from them extended with its infamy to the whole body of Christians.”

The Gnostic heresy, though in the 2nd century it had spread far and wide, was not of long duration. With it were extinguished, Eusebius tells us, all the aspersions on our religion. When he wrote, the old calumnies were dropped by all. Still, under Maximin, only a little before, the old charges were revived. In Damascus some harlots were forced by the governor into making a declaration that they had once been Christians, and had been witnesses of their wickedness. These confessions were engraved on brazen tablets, and were published all over the empire. Besides this, acts of Pilate, full of blasphemy against Christ, were forged; and then, by an imperial edict, all schoolmasters were provided with copies, and it was expressly enjoined that every boy should learn the lies by heart. Just then, “the devil had great wrath, knowing that he had but a short time.” Within a year the devil was chained.

When persecutors were reduced for evidence to such straits as we have described, it is plain how little occasion had been given to the adversary to speak reproachfully. Indeed, it may be fairly said, that at no time was this charge believed in by intelligent heathens. Certainly it was not believed in by the emperors Trajan and Marcus Aurelius, as their edicts published after inquiry show. The common people believed in it, no doubt; rumour and garbled quotations were sufficient for them, and very likely their belief was encouraged by the authorities as useful. But Roman governors knew, — aye, and acted on their knowledge, that there was one thing more terrible to a Christian woman than death itself. In the Diocletian persecution it was common to send Christian virgins to the houses of shame. The persecutors knew that a taint on Christian purity was more terrible than any punishment or any death. Surely enough has now been said on this subject; it would be well indeed if Christ’s Church could refute all the accusations made against her members as triumphantly as this.

We pass on to the second charge made against the Christians — the religious one. It was said that they were either worshippers of monstrous things, or that they were atheists and had no God at all. Here, too, the imagination of the heathen seems to have been their chief witness.

A common theory was that they worshipped the head of an ass. Tacitus, according to Tertullian, was the first to put the notion into people’s minds. He records a tradition that the Jews in their “exodus” were saved from perishing from thirst by wild asses, and that in their gratitude they consecrated a head of that animal to be their god. Arguing from the connection of Judaism and Christianity, the heathen supposed the Christians worshipped an ass’s head also. A little before Tertullian’s time, an apostate Jew, a man who hired himself out to fight with wild beasts, carried about through the streets of Rome a caricature of the God of the Christians. He was depicted as having the ears of an ass, hoofed in one foot, carrying a book, and wearing a toga. And the crowd, we are told, believed the infamous Jew.

Others said they worshipped the Sun. Perhaps there were two reasons for this charge. Sunday was the chief day of worship for the Christians, and they turned to the east whilst they said their prayers.

Others were convinced that they worshipped the Cross. Possibly the reason for this was, that the Christians were seen constantly to sign themselves with this sign.

The Emperor Hadrian confounded them with the worshippers of the Egyptian god Serapis. To him, in his attachment to the old Roman and Greek religions, all foreign religions were alike.

The martyrs’ bodies, rescued at such risk, and buried with such care, were thought by some to be the objects of their worship. Polycarp’s body was burnt lest they should abandon “The Crucified” and worship him. For the same reasons the bodies of some slaves martyred during the Diocletian persecution were cast into the sea.

The Apologists, in dealing with these charges, often wax sarcastic. Pretty fellows you heathens are, to make any objection to our objects of worship! Were all you say of us true, we should be much better than you. Why should you object to our worship of an ass’s head? You have gods with the heads of dogs and lions, and the horns of bucks and rams, and the loins of goats, and the legs of serpents, and wings sprouting from the back or foot. You say we are devoted to asses; but you must confess that you are worshippers of cattle of all kinds. You say we worship the Sun; many of you worship all the heavenly bodies and the clouds. You say we worship the Cross; you undoubtedly worship your military standards.

It may have been injudicious to retort thus sharply whilst making a plea for permission to exist; but, policy apart, the reply is effective enough.

Probably the charge of atheism was more popular and more seriously believed in than any of the above. Men so well hated as the Christians, were sure to be attacked by scandalous reports not half-believed. But the charge of atheism seemed to rest on a good foundation, for the Christians had, or seemed to have, none of those accessories of worship used by all other religions. Certainly the charge made the common people hate them more intensely.

The position of the common people with respect to their religion was in some points very similar to the position of many people now. When all went well they did not trouble themselves much about it; but when misfortune came they were filled with guilty fears. In prosperous times they were wont to offer in sacrifice worn out, scabbed, and corrupting animals; or they would cut off the head and the hoofs — the portion assigned to the slaves and dogs — and offer them upon the altars. Tragic and comic writers did not shrink from setting forth the gods as the origin of all family calamities and sins. Men had no objection to making merry over the story of their weaknesses and crimes; dramatic literature pictured their vileness; and when their majesty was thus insulted and their deity dishonoured, the world applauded. Even the sanctity of the temples was not respected, they were convenient places for the most licentious deeds. But when disasters came — as in the second century they constantly did — then superstitious fear filled the hearts of all. It was said at once, the gods are angry because their temples have been deserted and their rites neglected. At such times the Christians were a convenient scapegoat. Public religious ceremonies, rain-sacrifices, barefoot processions, were enjoined; and in these the Christians would take no part. Then there were popular risings, all forms of law were set at nought, and this to such an extent that the authorities had to interfere. Tertullian tells us that the heathen thought the Christians the cause of every public disaster and affliction. If, he says, the Tiber rises as high as the city walls, if the Nile does not send its waters over the fields, if the heavens give no rain, if there is an earthquake, if there is a famine or pestilence, straightway the cry is, “Away with the Christians to the lion.” It was Nero who set the fashion of ascribing calamities to the Christians; and his example in this respect was constantly followed in later times. The martyrdom of Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, seems to have followed on a destructive earthquake. The persecutions under Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, and Diocletian, followed after various public calamities — pestilences, inundations, earthquakes, and fires. Maximin boasted that his persecution of the Christians had brought back again to the world long-lost abundance, peace, and health. So prevalent indeed was the idea that the Christians were the guilty causes of the calamities of the times, that many of the Apologists set themselves to show that there was no real connection between them. For the most part the Apologists deal with this matter by pointing out that national disasters occurred long before Christians were known, and that the times are not so bad after all. Seasons of scarcity are relieved by times of plenty, disasters in war are compensated for by victories and successes.

“It is three hundred years,” says Arnobius, “since we Christians began to exist. Have wars been incessant? Have the crops always failed? Has there never been peace and plenty on the earth? On the contrary, there have often been the most plentiful yields of grain and seasons of cheapness. Victories innumerable have been gained. The boundaries of the Empire have been extended. It would be quite as fair to attribute your prosperity as your calamity to us. Moreover, is it seemly to ascribe anger and spite to the immortal gods? Do such passions dwell in heavenly minds? Again, if we are the offenders, do the gods need your strenuous advocacy to avenge the insults offered them? By heat and by cold, by tempest and by disease, they can consume us and drive us from the earth; why do they not put forth their power if they are really angry? Moreover, if we alone are the offenders, why does not the punishment fall on us alone? To you let them give good health, to us the worst. On your farms let them send seasonable showers, on ours let them drive away all gentle rain. Let your sheep multiply, and ours be barren. Let your oliveyards and vineyards give their full increase, let ours give not even a single fruit. Let them make the fruits of the earth nutritious to you, but to us let the honey be bitter, the oil rancid, and the wine vinegar. Such is not the case now. To us who are impious no less share in the bounties of life accrues than to you who are pious. On you as well as on us misfortune falls.”

Tertullian points out that many calamities befell the world before the coming of Christ. Islands were swallowed up by earthquakes, the world was destroyed by a flood, Sodom and Gomorrha, Vulsinii and Pompeii were destroyed by fire, the Romans were defeated at Cannae, and their Capitol was besieged, long before the mention of the Christian name. Indeed, as a matter of fact, the Christians lighten the calamities which come upon the earth. When the heathen, with their sacrifices and processions in the times of their calamity and anxiety, are supplicating the gods for deliverance, the Christians, by fasting and prayer, by abstinence from sin and even ordinary enjoyments, assail heaven with their importunities. They touch God’s heart, and He is merciful; but Jupiter gets the honour.

Cyprian, in replying to Demetrian, the proconsul of Africa, on this matter, has quite another theory. He confesses that in winter there is not such an abundance of showers, nor in summer so much sun to ripen the corn, that marble is dug in less quantity from the mountains, and that the gold and silver mines show signs of early exhaustion, that strength, skill, and innocence are all failing; and the reason is, the world is growing old.

The Apologists are very careful to free the Christians from the charge of impiety and atheism. Though they do not worship the gods of the heathen, they do serve and worship God.

“To adore,” asks Arnobius, “God as the highest existence, as the Lord of all things that be, as occupying the highest place among all exalted ones, to pray to Him with submission in our distresses, to cling to Him with all our senses (so to speak), to love Him, to look up to Him in faith — is this an execrable and unhallowed religion, full of impiety and sacrilege, polluting by its novel superstition ancient ceremonies? Is this the daring and heinous iniquity on account of which the mighty powers of Heaven whet against us the stings of passionate indignation; on account of which you yourselves, whenever the savage desire has seized you, spoil us of our goods, drive us from our ancestral homes, inflict upon us capital punishment, torture, mangle, burn us, expose us to wild beasts, and give us to be torn by monsters? Does he deserve the name of man who makes such a charge? Can he be reckoned amongst the gods who charges with impiety those who serve the King supreme, or is racked with envy because His Majesty and worship are preferred to his own?”

Of course it is very easy to see how the charge of atheism arose. The Christians had no temples and no images, they would take no part in any of the ceremonies of the State religion. Their whole life showed that they despised and loathed heathenism.

Celsus says, “The Christians cannot so much as endure the sight of the temples, altars, and statues.” The Christians have no temples, therefore they have no gods, was a convincing argument to a heathen. His religion was purely an external one. It concerned his nation, it concerned his family, it affected his public and domestic life, but it did not purify his desires, and it did not influence his heart. Disbelief in a god was no reason for not sacrificing to him; if the object of desire was criminal, that again was no reason for omitting to ask a god’s help. All alike were content to make utility the foundation of religion. Philosophers and statesmen said, with more or less certainty, The religion of the gods is false; but they felt the masses could be hardly controlled without it. The Roman people generally said, By venerating the gods Rome has reached its present height of prosperity. From neglect of the auguries experience tells us disaster has often come. The Christians, who despise the gods, are enemies to the State.

The third charge brought against the Christians, and, in some respect, that of the most importance, was of a political nature. They formed, it was said, a secret society, they belonged to an unlawful and new religion, they were disloyal to the Emperor, and unprofitable to the State.

The jealousy of the Romans against secret societies was very great. The Emperor Trajan went so far as to forbid the formation of a company of firemen at Alexandria. There was necessarily much secrecy about the Christians and their religion, and there was besides much about them to excite suspicion. They were a body of men of all nations growing and spreading every day. They were united by some tie for some unknown purpose; this purpose was plainly of the greatest importance, for everything reckoned valuable by others was neglected by them; the world’s honours and the world’s pleasures they alike despised. Vague reports of a kingdom which they were setting up were continually floating about, and that was quite enough to excite jealousy in the mind of any Roman governor. Every now and then glimpses of their aims would be seen, and these were nothing more or less than the subversion of the State religion. The Christians, then, belonged to a secret society, and one, apparently, of a dangerous character. But this was not all, Christianity was an “unlawful” religion — a “new” religion. Now, at first sight it might be thought that one more or one less religion would not have been considered a matter of much importance. The heathen religions were more numerous than the Christian sects now. The heathen had gods many and lords many, and fresh ones were springing up every day. The Roman government was tolerant of all religions. It never called together all peoples, nations, and languages, to worship the golden image which it had set up. No one was persecuted for his opinions; it was quite an understood thing that different nations had different gods. A religion was, as it were, a national characteristic. Just as one nation differed from another in colour, language, customs, and laws, so it differed also in the gods which it worshipped. So it came to pass that the Romans, when they conquered a nation, and incorporated it into their Empire, incorporated also its gods into their Pantheon. Rome, the Mistress of the world, Alexandria, the meeting-place of the world, were the homes of all religions; temples to the different gods stood side by side. The gods and the nations were supposed to be suited the one to the other; the gods took care of the nations, and the nations worshipped the gods. Everybody worshipped the gods of his fathers after the rites of his fathers, and the Government was not careful to inquire what those rites were. Gallio represents the indifference of the Roman State when he said, “If it be a question of words and names, and of your law, look ye to it ; for I will be no judge of such matters.” But religions being, according to the Roman idea, national characteristics, they could not be changed any more than you could change your nation. Proselytizing was a thing strictly forbidden, it overthrew the object of religions altogether. By the aid of religion, order was much more easily kept; that, indeed, according to some, was its chief use. A superstitious fear, a Roman historian says, was the mainstay of the Roman State. But proselytizing implied controversy, and angry passions, and tumults, and disorder, and all for a mere nothing. One god was, to all intents and purposes, as good as another; and the gods of a nation had a claim on the worship and veneration of the members of that nation.

Now, of course, Christianity could not reap the benefit of such toleration as this. It proclaimed with a loud voice that there was but one God for all nations. In its very essence it was aggressive; the work of its ministers was to go out into the highways and hedges, and compel men to come in. It set itself to the ridiculous (as it seemed) task of bringing all the inhabitants of Asia, Europe, and Libya, Greeks and barbarians, those dwelling in the uttermost ends of the earth, under one law. It interfered with the worship of the national gods, and moreover, it repudiated that worship of the Emperor by which the Romans thought they could unite the world in one religious bond. Very soon we find the Christians overpassing the bounds of Roman tolerance. They were found to be disturbers of the public peace. They would not leave other people alone, and therefore they were not left alone. The history of the Church in the New Testament shows us this. To avoid a tumult Pilate ordered Jesus to be crucified. Paul is scourged at Philippi as an exceeding troubler of the city. At Thessalonica he is described as a man who has turned the world upside down. He excites disturbance wherever he goes, and is ultimately sent to Rome because of an uproar at Jerusalem. Perhaps it was tumultuous gatherings arising out of Christian controversies which caused the Jews to be expelled from Rome in the reign of Claudius. It is evident that on the Christians would be laid the blame of all such tumults. From a political point of view they were justly blamable. The view of the Roman authorities could be none other than this. This man’s teaching attacked people’s prejudices; being what it was, it could hardly fail to make them angry, and excite disturbance. We must suppress him, and those like him, if we would have peace.

The “novelty” of Christianity was no unimportant item in the charge against it. “This new religion,” Lucian calls it scoffingly. “Why has this new kind of practice entered so late into the world?” was the question of Diognetus. “Your doctrine has but recently come to light,” was the common taunt. To bring back the observance of the ancient institutions, ancient laws and discipline, and the worship of the ancestral religion, was the aim of the very last persecution. “The ancient religion ought not to be censured by a new,” is a statement in one of Diocletian’s edicts. “It is the greatest of crimes to overturn what has been once established by our ancestors, and what has supremacy in the State”; “It is an act of impiety to get rid of the institutions established from the beginning in the various places,” says the philosopher Celsus. It was not difficult to answer the objection based upon the novelty of Christianity. Arnobius points out the improvements in science, art, and civilization, and asks whether they are any the worse for being new. He notices that the Romans are constantly changing their habits and modes of life. Granted that the heathen religion was old, it was only a question of degree. “The belief which we hold is new, some day it will be old; yours is old, but at its rise it was new and unheard of. The credibility of a religion cannot be determined by its age, but by its nature. Four hundred years ago our religion did not exist, we admit. But two thousand years ago your gods even did not exist. Does the Almighty and Supreme God seem to you something new, and do those who adore and worship Him seem to you to be introducing an unheard-of, unknown, and upstart religion? Is there anything older than He? Can anything be found preceding Him? Is not He alone uncreated, immortal, and everlasting? Our religion is not new in itself, but we have been late in learning the true object of worship. Our religion, it is true, has only lately sprung up on the earth; and the reason is, He who was sent to declare it to us has but lately appeared. Do you ask why this was? We answer, We do not know. We cannot explain the plans of God. But this we may say; in eternal and unbounded ages nothing whatever can be spoken of as late. Where there is no end and no beginning, nothing is too soon, and nothing too late.”

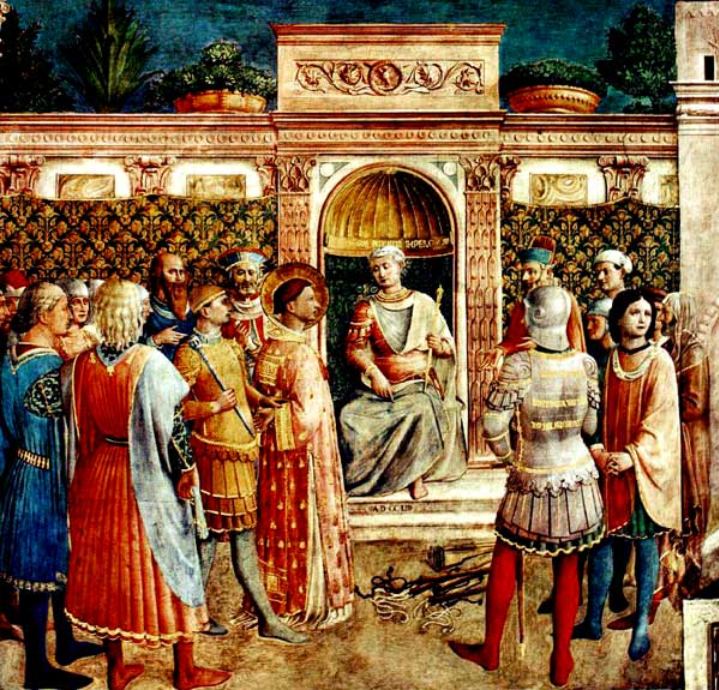

And now we are in a position to state the precise way in which the Christians during the first three centuries became obnoxious to the law. They be longed to a religion, not venerable for age, not allowed by law, and not national. They belonged, moreover, to a religion, which, instead of promoting order, caused dissension and tumult all over the world. Christianity, being what it was, could not be placed on the list of allowed religions; to belong to it was therefore a legal offence. In consequence, a Christian’s trial was a very simple thing. He was dragged before the judgment-seat by the mob for his unnatural crimes, or for his atheism. The former charge was very difficult to prove, and as for the latter, the judge was probably himself an atheist by conviction; still it was not politic to let him go, for a tumult was made. The judge, like Pilate, often wished to release him; some times he ran all risks, and did release him, but more commonly he let the people have their own way. He condemned in legal fashion a man who was unjustly accused. Not his immorality, or his atheism, but his Christianity was the legal charge on which he was condemned. The law said, “The Christians are not permitted to be.” The judge had only to ask, “Are you a Christian?” He had only to obtain the confession, “I am,” and then there was no need to inquire further into other matters. The Christians, as such, were liable to torture and death.

“Are you a Christian?” This is a simple question to us, but it is one which has caused many a stout man’s heart to quail. “Are you a Christian?” He had but to say, No; he had but to throw a little incense on the fire, he had but to revile the name of Christ; and then at once he would be dismissed unhurt, confirmed in his office if he had one, with his property untouched, and his reputation unsullied. He might have been a Christian in days gone by, the law would forgive him that; he might still be a Christian by conviction, of men’s opinions the law took no cognizance; if from henceforward he conformed outwardly to the State religion, that was sufficient, the law asked for nothing more.

And soon, too, the authorities discovered that denial and apostasy gave them more than they even asked. The Roman governor with a sneer on his face, the mob with outspoken jeers, the Christians with heartfelt prayers and pity, marked the pale face and hesitating look of the accused, and one and all knew that if he said, “No, I am not a Christian,” a Christian ipso facto he was no longer. Open denial and apostasy could only be purged by an open confession. And thus all learnt the fact that a Christian’s words and deeds were in closest harmony. A philosopher had no objection to take the test and swear by the gods which he had proved had no existence. A Christian who denied the name of Christ ceased to be a Christian in any sense whatever.

If, then, the prisoner pleaded, “Not guilty,” his plea was accepted, and he was released. But if he pleaded “Guilty”; if he said, “I am a Christian,” what then? Then the struggle began. Surely it is an almost incredible fact in the history of trials of justice, that the attempt should be made to compel men to confess that they were innocent of the crime laid to their charge. Yet so it was. Torture was applied, not to make the accused confess, but to make him deny. That was the great aim the law always had. The desire was, not to punish men who had been Christians, but to exterminate Christianity. It is Tertullian who brings this strange mode of procedure clearly before us. He pictures a man replying to the question with the words, “I am a Christian.” “He tells you what he is,” says Tertullian; “you wish to hear from him what he is not. Occupying your place of authority to extort the truth, you do your utmost to get lies from us. ‘I am,’ he says, ‘that which you ask me if I am. Why do you torture me to sin? I confess, and you put me to the rack. What should you do if I denied’? Certainly you give no ready credence to others when they deny; when we deny, you believe at once.” Tertullian sees in this a proof that it is the Christian name which is being pursued with enmity. “We are put to the torture if we confess, and we are punished if we persevere, and if we deny, we are acquitted, because all the contention is about a name.” He points out that the authorities, treating the Christians thus differently from criminals, recognize the fact that Christians are indeed guiltless of crime.

The accounts of Christian trials which have come down to us, all confirm Tertullian’s statement. The question and the answer on such occasions seem to have been nearly always the same. “Are you a Christian?” Pliny asks those brought before him. When they confess, he repeats the question twice, with threats ; when they persist, he orders them to be punished. “I am a Christian,” says Polycarp (they did not need to ask him). To the invitations, “Swear by the fortune of Caesar”; “Repent, and say, ‘Away with the Atheists’!” “Swear, and I will set thee at liberty”; “Reproach Christ,” — the same simple statement is his only reply. Through the Stadium the proclamation is thrice made, “Polycarp has confessed that he is a Christian.” And then the only doubt is, what death he shall die. One question only is asked of Ptolemseus when accused before Urbicius at Alexandria; as must needs be with a true Christian, confession is made, and condemnation at once pronounced. A bystander protests, and asks, “What is the ground of this judgment? Why have you punished this man, not as an adulterer, nor fornicator, nor murderer, nor thief, nor robber, nor convicted of any crime at all, but who has only confessed that he is called by the name of Christ?” The only answer the question gets is, “You also seem to be such an one.” It is promptly replied, “Most certainly I am,” and he too is led away to death, to be in his turn followed by a third. “Are you a Christian?” is the question of the prefect Rusticus to Justin and his fellow-martyrs. “I am a Christian,” each replies in turn, “by the command of God,” “by the grace of God,” “being freed by Christ.” ” Do what you will, we are Christians, and do not sacrifice to idols.” Immediately sentence is pronounced. What need is there of any further instances? The same is true throughout the period of persecution; and is it not cause for deep thankfulness and for pride, that our brothers, following the Apostolic command, did not suffer as murderers, or thieves, or evildoers, or busybodies in other men’s matters; but they suffered as Christians, and were not ashamed, but glorified God on this behalf.

But it was very hard for them to resist to blood, when a word would have set them free. Throughout, it was the great object of the judges to make the Christians say that word. Sometimes threats were used; the confessors were threatened with the flames, or the wild beasts, or the brothel. Sometimes a free pardon was offered to all who renounced their faith, whilst instant death was inflicted on those who still stood firm. Sometimes a man was begged to have respect to his old age, sometimes to have compassion on his youth. Sometimes friends did their utmost to make them recant. A grey-haired father throws himself at his daughter’s feet, and with tears he implores her. “Have pity, my daughter,” he says, “on my grey hairs. Have pity on your father, if I am worthy to be called a father by you. If with these hands I have brought you up to this flower of your age, if I have preferred you to all your brothers, do not deliver me up to the scorn of men. Have regard to your brothers, have regard to your mother and to your aunt, have regard to your son, who will not be able to live after you.” The procurator says, “Spare the grey hairs of your father, spare the infancy of your boy, offer sacrifice for the well-being of the emperors.” She answers, “I will not do so.” He asks, “Are you a Christian?” and she replies, “I am.” Then there was but a step between her and death. But not all were brave and constant, many were overcome by torture, or over-persuaded by their friends. Specially was this the case in the later persecutions. A time of peace and quiet had its drawbacks, it added those to the Church who in times of persecution were ready to fall away. The number of apostates in the Decian and Diocletian persecutions was very great; and, the persecutions over, the Church found the greatest difficulty in dealing with them when they asked for re-admission to communion. The orthodox teaching was very strict. Some of the heretics said that you might deny Christ with your mouth but still confess Him in your heart. The Church always held that those who formally or virtually apostatized committed sin almost if not quite beyond forgiveness on earth. Years of repentance had in every case to precede restoration to full Christian privileges.

Gallienus, in the year A.D. 259, was the first emperor who recognized Christianity as a legal religion. Up to that time the Christians were always liable to be persecuted. The law was against them, although the Emperor or the governors might be on their side. Gallienus gave to the Christians the free exercise of their religion, and the right of holding property; and thus placed the law on their side. The liberty then first granted was withdrawn by later emperors; it was not till Constantine’s time that Christianity was firmly established in its position. Under him it became not only an allowed religion, but the religion of the State.

We pass on now to the next political charge, viz., disloyalty to the Emperor. The Christians had “another king, one Jesus”; this was the fact which at first excited the jealousy of the State. But when it discovered, as it soon did, that the Christian kingdom was “celestial and angelic, and to appear at the end of the world,” it ceased to trouble itself about the matter.

The foundation for the charge of disloyalty was quite different in later times. The Christians were reckoned to be disloyal to the Emperor because they refused to reverence him as divine, to swear by his genius, and to celebrate his festal days. They would not make a god of him, in fact, and so they were reckoned to be traitors.

The Apologists tell us that the Christians were quite ready to pay all human honours to the Emperor; that they prayed for, served, and honoured the Emperor as pious and loyal subjects should. They point out the fact that no Christians are found amongst the conspirators. Indeed, such a thing is impossible, for their religion forbids them to wish, do, speak, or think evil of any one. The Christians, they say, have a special interest in the prosperity of the Roman empire, for they believe that with its fall violent commotions will come upon the world.

The last political charge is unprofitableness to the State, and perhaps no charge had more real foundation in fact.

When we examine the history and read the literature of the Early Church, we cannot fail being struck with the all-absorbing character of Christianity in those early times. A Christian had the hopes and the promises of his religion, and for the most part he had nothing else to call his own. He looked back on the life of Christ Incarnate. He looked forward to the coming of Christ in power and great glory. Both events were very near to him. Christ had but lately come; Christ was very quickly to come. The cloud had but just received Him out of his sight; the clouds were already gathering to accompany His return. There was nothing on the earth for him to delight in. He had no hold on its riches or its honours, for he could not reckon even on his life. Any day he might have to give up all for Christ, and any day Christ might come again. The state of the world in which he lived, the rapid approach of the world to come — both these produced in him a remarkable singleness of aim.

Hence arose the charge that the Christians were unprofitable citizens. The later Apologists invariably refer to it. Tertullian denies its truth. “How in all the world,” he says, “can that be the case with people who are living among you, eating the same food, wearing the same attire, having the same habits, under the same necessities of existence?” “We sojourn with you in the world, abjuring neither forum, nor shambles, nor booth, nor workshop, nor inn, nor weekly market, nor any other place of commerce. We sail with you, and serve in your armies, and till the ground with you. In like manner we unite with you in your trafficking; even in the various arts we make public property of our works for your benefit.” The Christians, he tells us, had their own costly religious ceremonies. They spent much on charity, and defrauded none of their due. They did not pander to the luxury and vice of the age; but that was no loss to the State. They cost the Government nothing as criminals, and they alone reckoned themselves to be responsible for their words and looks as well as their deeds. Such is Tertullian’s defence in his Apology. It seems to be pretty complete, considering the times and the position of the Christians. Unfortunately, in other places, Tertullian seems to contradict himself. He tells us the Christians have in this world no concern, but to depart out of it as quickly as they may. Lactantius again denies the lawfulness of all pursuit of gain.

With principles like these, there would be few busy, thriving merchants among them, ministering either to the luxuries, or even the wants of the people. For another reason, also, commerce was almost closed to them, for they could not protect themselves when cheated. The forms of the law-courts were idolatrous, so that they could not be used with a clear conscience. It was doubtful whether, under any circumstances, lawsuits could be permitted. “It does not become,” says Tertullian, “the son of peace to sue at law.” The Christians took no part in politics, they despised and refused all temporal honours and ensigns of magistracy. For conscience sake, as we have seen, they abstained from the public games and the temple worships; they brought no custom to the multitudes who derived their livelihood from one or the other. More than all, some of the Christians had conscientious scruples connected with the lawfulness of the profession of arms. Tertullian says, “There is no agreement between the divine and human sacrament, the standard of Christ and the standard of the devil, the camp of light and the camp of darkness.” If a soldier become a Christian, he says, he must either quit the service or suffer for God’s sake. Many of the Apologists held the same opinion on the incompatibility of the military service with the service of Christ. Origen says, “None fight better for the king than we do. We form a special army for him, an army of piety, by offering our prayers to God; but we do not fight under him, even if he require it.” A soldier’s duties often brought him in corrupting contact with heathenism: he had to keep guard over the temples, and take meals in them; he had to protect the heathen gods, and had to carry idolatrous flags and badges; he had to take idolatrous oaths, and to join in idolatrous ceremonies. Under the circumstances it was almost impossible for a Christian to be a soldier. Tertullian went even further, and settled the matter on abstract principles. The Lord had taken away the sword; in disarming Peter he unbelted every soldier.

It is impossible to conceive a course of conduct better adapted to enrage the Roman Government than this. They could hardly be expected to tolerate the refusal of such a numerous body of men to serve in the ranks as soldiers and to fulfil their duties as citizens. They naturally asked what would become of the State if all were Christians; if there were none to fill the public offices, to provide for the public necessities, to fight against the public foe. It is true not all the Christians were thus, by their principles, made useless in the affairs of the world. Clement’s exhortation is, “Practise husbandry if you are a husbandman; but while you till your fields, know God. Sail the sea, you who are devoted to navigation; yet call the while on the heavenly pilot. Has knowledge taken hold of you whilst engaged in military service? Listen to the commander who orders what is right.” But in the rise of a new party, the eccentricities or violent statements of a few extreme members are invariably placed to the credit of the whole. In this case the heathen and social systems were so closely intertwined, that a Christian could not join in many of the pursuits of the day. In those open to him, conscientious difficulties were constantly in his path, and dangers to his property and life were continually threatening. Not wishing to court martyrdom, he took refuge in obscurity; and thus incurred, with some reason, the charge of neglecting his duty as a man living in the world, and as a citizen in the State.

And now our description of “The Defence” is complete; we have seen all that the heathen had to say against the Christians, and the reply the Christians were able to make. Happy would it have been for the Christians, if their enemies had never been able to accuse them with so little truth, and if their champions had always been able to reply with such convincing force.

4.5

What changed with the website? RSS feeds don’t work anymore, this is the last article my reader pulled, and your previous chapter links at the end of this article for example, don’t work….

nvm, figured out the new rss links. Links still point to wrong url though.

Thanks for alerting us to this problem. We are working on fixing the links.

np, i’m no wordpress expert, but could you just change the permalink settings of this new template to match the old template? because this change will break anyone else’s old links to your site as well.