Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 8 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 7: The Mainit River Bridge)

____________________________________________________________________________

“This action in the Philippines is the decisive battle in which we cannot withdraw even a single step, for we have burned our bridges behind us…. It is a great decisive battle on which the life of the Greater East Asia war depends, for it decides whether we lose our sea routes to southern regions.”

(Radio Tokyo on the Battle of Leyte)

____________________________________________________________________________

Day or night, in the tent of the Division Intelligence near Palo, work never ceased. The coding and decoding machines ticked without cessation. Enemy messages were snatched from the ether. Enemy documents found or captured, from a soldier’s paybook to a colonel’s diary, were subjected to thorough analysis. The stream of people summoned for questioning never ended: prisoners of war, guerillas, itinerant tradesmen, missionaries. Photographs were pieced together and translated into maps. A tight-lipped sergeant burned with care each scrap of waste paper spewed out by Intelligence. When the sorting was done, a picture resulted upon which the disposition and the missions of the combat teams were decided.

On the morning of October 26, messengers rushed from Division headquarters to the town of Castilla where the Nineteenth Regiment had established its roost. Soon other messengers were on the way to the battalions and the companies. After a relatively quiet night the “Rock of Chickamauga” was alerted for action.

Guerillas operating in the mountains brought the news that Japanese detachments were on the march to reinforce General Shiro Makino’s badly mauled Sixteenth Division in the Leyte Valley. Aerial observers reported that enemy troop barges had entered Ormoc Bay, in the west beyond the almost trackless central range. Intelligence fitted together the pieces. It was learned that the Thirtieth Japanese Infantry Division had left its bases in Mindanao, Leyte-bound. Other reinforcements were signaled as being on the way from Cebu and Luzon.

There were but two roads by which the enemy could pump fresh forces into Leyte Valley, or escape from it. One led through Carigara in the north, the objective of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment’s offensive; the other led up from the south through wild hill country by way of the town of Pastrana. The Nineteenth Regiment was given the mission to seize Pastrana and block the latter route. It was also ordered to secure the mountain passes of the central range.

The sky was leaden. Sultry heat lay heavy on the helmeted men. The leading battalion followed a trail flanked by thickets which trapped the heat. The trail led steadily uphill. For stretches the kunai grass had grown together above the path and then it was as if the advancing platoons were following the course of a stifling and saturnine tunnel. “Item” Company formed the advance guard. Mortarmen, machine gunners and ammunition bearers panted under their loads. Some soldiers dropped from heat exhaustion; they were revived with water from their own canteens, helped to their feet, and pushed on with glazed eyes.

Whenever the scouts approached a bend in the trail, an air of stealthy alertness took hold of their sweat-drenched shapes. Their gait slowed. Their steps became longer, gliding. When sudden shots crackle from ambush, it is normally the leading scout who is the first to fall.

To be made a scout in jungle war is somehow akin to being selected for death. Good squad leaders select their best men to serve as scouts. Some, intent on keeping old friends alive, selected green replacements for the job. Most did not live long. But the scout shrugs, and pushes on, wary, unhappy, and aggressive. A bend in the trail: the scout grasps his rifle tighter; he probes to right and left, and forward. He knows that in the mystery of jungle growth the enemy can lie in wait and not be seen within a whisper’s reach. Most often the first shot of an invisible marksman is the first herald of battle. The scout rounds the bend in the trail simply because there is nothing else to do. For a moment he pauses. He peers forward and to the flanks, and if no one shoots at him during those seconds, he regains his stride.

The first shot was fired a mile from the outskirts of the town of Pastrana. The scout fell. The shot came from an Arisaka rifle, from the immense crown of a breadfruit tree. The vanguard dispersed. It formed a skirmish line and flushed the thickets and treetops with fire. The sniper pitched out of the breadfruit tree. The first of many that day.

Bullets whined. They scuffed up the black earth in many spots as the advance struck the fringe of the town. The battalion pulled back, organized in assault formations, then attacked, two companies abreast, a third closely in support. The town square in sight, the charge was halted. It was thrown back by one of the most unusual fortifications encountered in the Japanese war.

The repulsing fire pounded out of what looked like a cluster of flimsy houses. But men in the forward attack waves noticed that green grass seemed to grow halfway up the sides of the huts. Men died. Many were wounded. A sergeant closest to the wall of fire said in a loud voice, “Why should grass grow up the sides of shacks?”

Twenty-four hours of savage fighting went by before the stronghold could be explored. What had resembled grass growing on the walls of huts was really a star-shaped revetment built of layers of heavy logs, reinforced with concrete and covered with mounds of earth. Grass had been made to grow over the mounds. The native houses had been built over a group of pillboxes. Other pillboxes protected the flanks of the fort. Their reinforced concrete walls were two feet thick, and they commanded clean fire lanes in all directions. Tunnels and trenches connected the various strongpoints. The whole had been built with cunning care. Part of the camouflage were foraging pigs, and women’s clothing hung on lines as if put there to dry.

Mortars failed to breach the fort. The revetment sneered at machine gun bullets. Flame thrower and demolition teams were not able to advance near enough to do their part.

The assault force backed away. The fire fight continued. The men looked vicious and frustrated. Also, they were hungry. The heat was intense. Here and there were growls: “Let’s get in there so we can cool off and eat.”

The regimental commander called for artillery fire. The infantrymen crouched low and watched their shells engulf the star-shaped fort. Smoke billowed and there were shattering explosions. Suddenly there was silence, and a dry voice said, “Fix bayonets.”

Quietly the command was passed along the skirmish lines. Then machine guns chattered and infantry jumped off to attack anew. The sun was setting.

The fort heaved and roared. It vomited thousands upon thousands of bullets. Under the somber gold and crimson of the cloud-filled sky the charge penetrated to within one hundred yards of the fort. There it was stopped. Casualties were heavy. The order was given, “Stay there, and dig in.”

From among the huddles of the dead in the debris-strewn strip of no-man’s-land came a faint cry for help. A wounded man raised himself to his elbow. He waved one hand feebly. The movement drew immediate machine gun fire from one of the pillboxes flanking the fort. The movement stopped. But soon the faint cry for help again came to the digging men. A sergeant said: “Somebody’s got to go and drag the guy in.” The sergeant was Harold Schmidt, of Ortonville, Minnesota.

In the half-concealment of battered bushes and wrecked shacks men looked at one another. Except for the cracking of rifles and the hard stutter of a machine gun, there was silence. The wounded soldier lay a scant twenty yards in front of four Japanese pillboxes. The digging men could hear his cries. Their lips were thin lines. Nothing could be done. In the night the Japs would crawl out and kill the wounded. That was one reason why so few Jap prisoners were taken. The enemy wounded? Give them a bullet, or the knife, then kick them in the face and rob them.

Again there came a cry for help; thinner now, like the plaint of a crushed child.

“Christ, we can’t leave the guy,” said Sergeant Schmidt. “We’ll be listening to him all night.”

From the fort came the sound of outlandish singing. A Japanese field gun opened up. All night it dropped scattered shells over the perimeter. In their holes the men ducked low. They listened to the crashing rumble of the bursts and to the twang of fragments among swarming fireflies. Sergeant Schmidt put aside his shovel. He sat back on his haunches and prayed. Then he tightened the chin strap of his helmet. He grabbed two grenades and he crawled out and forward into the assembly of corpses.

He found the wounded man and cut away his clothes with a bush-knife. From his jungle kit he took sulfa powder and a bandage. He sprinkled the sulfa on the other’s bullet wounds and after that he bandaged them and stopped the bleeding. The Japanese saw the stirring of dim shapes in murk. They fired.

“Easy now,” Sergeant Schmidt said to the wounded soldier. “We are going home.”

Inch after inch, foot by foot, he dragged his helpless comrade back to his own perimeter. Harold Schmidt was later killed in action.

At another sector of the Pastrana front a wounded man limped in with the message that two other soldiers lay badly mangled in front of the hostile lines. The spot was covered with wicked fire from a spider-hole. A corpsman made ready to go. But he needed help. “I’ll help you,” a quiet voice said. The words were spoken by an army chaplain, Harry G. Griffiths, whose home is in Clyde, Ohio. Together the aid man and the chaplain braved death to bring the wounded to cover. It was the second time in the campaign that machine gunners had aimed their bullets at the chaplain.

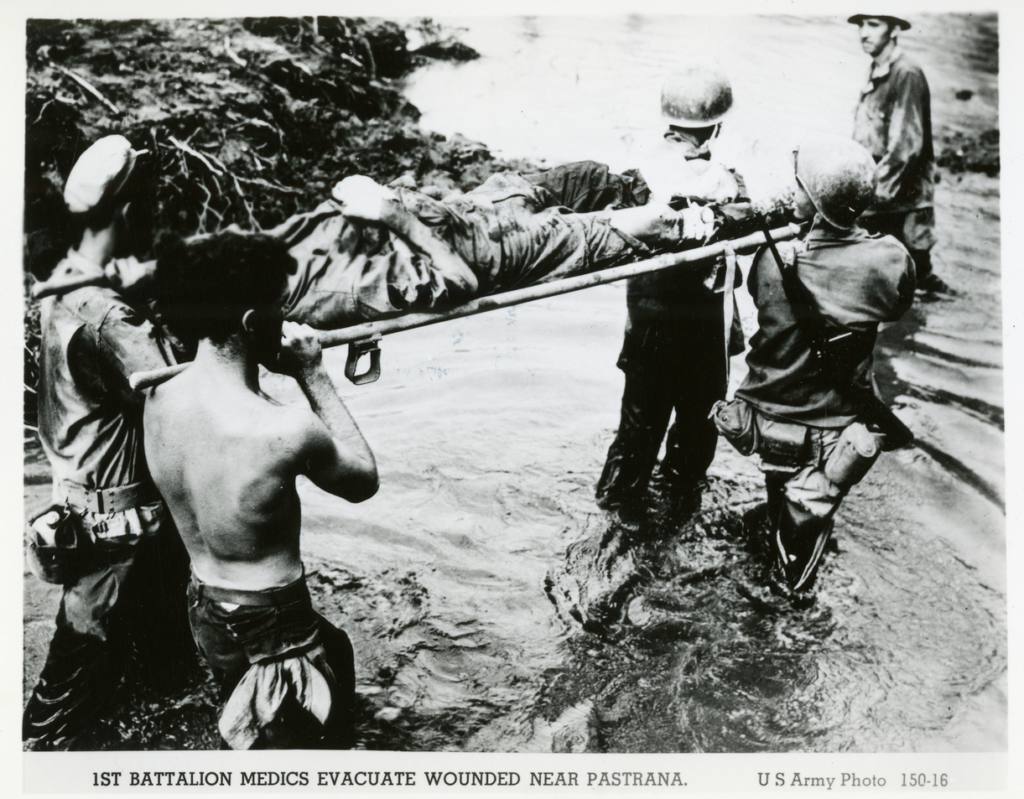

From dusk to dawn the Division’s field artillery hammered the star-shaped fort. Huddled in muddy three-man holes, the assault force rested. The wounded of the day’s collisions were evacuated to the rear. Enemy raiding parties repeatedly interrupted communications with Palo and Castilla; they cut wires and ambushed trucks and ambulances at dark road bends and near by-passes around demolished bridges. Rain squalls struck between midnight and dawn. Beneath the screaming of shells and the rolling thunder of explosions a hundred yards to the front, few managed to snatch sleep. Jap planes droned overhead. They were bombing the road, the cluttered beach, the supply ships in San Pedro Bay; and one could hear the squealing of Japanese in the darkness whenever there was a lull in the artillery concentration.

With the first tints of a pearl-shell dawn the artillery ceased firing. Batteries of heavy mortars continued the barrage. They lobbed their explosives from close-range emplacements which the mortarmen had dug overnight. With daylight, infantry teams attacked.

They overran the fort. Surviving Jap guns unleashed a frantic final clatter. The riflemen swept through Pastrana and carried the town in house-to-house fighting. Consciously they fought for nothing more than a chance to flop down and sleep. The field piece which had shelled the American perimeter all night was captured at the northwestern edge of the town; its gunners committed hara-kiri by grenade. “King” Company pushed beyond the outskirts of Pastrana. Its soldiers set up a roadblock near a burned-out bridge astride the highway to Dagami. This severed the enemy’s route of escape. Jap mortar fire fell on Pastrana in the afternoon. One shell fell into an aid station. Three American wounded were killed.

Japs died hard. Surrounded, out-gunned, out-numbered, they did not give up in battle. A Japanese soldier forced to make a decision would first seek for an attack-solution of his dilemma. He is a believer in the “spiritual power” of the bayonet. In Pastrana he fought to the last and had to be rooted out, and killed, one by one. Scattered detachments and snipers harassed the town for days.

The star-shaped fort was a shambles. Its gloomy caverns were broken and the network of trenches and bunkers was carpeted with twisted dead. Many had been torn limb from limb by the bursting shells. Many showed no visible wounds, but the force of the concussions seemed to have broken every bone in their bodies. Forty Japanese weapons trucks were destroyed in the assault. Scores of automatic weapons were captured. There were forty-one machine guns which had supported the defenses of the fort.

The storming of Pastrana by three thousand Americans was punctuated by many deeds which the sweat-encrusted men in front shrug off as incidental to a hateful job. Portly Brigadier General Cramer walked through sniper fire unscathed; not once did the proximity of death ruffle this soldier-senator’s bluff efficiency. “If you want to find General Cramer,” the dogfaces of the Nineteenth tell you, “don’t look at headquarters, look for him where the shooting is.” Where Cramer walked untouched a minute before, Captain James B. Jones of Buffalo, South Carolina, an operations officer, did not. A sniper’s bullet pierced his leg. The captain emitted an oath and sat down. An aid man bandaged his wound. After that, Jones limped to the nearest bush and cut himself a stick. Then he continued on his mission, which was to coordinate the actions of the battalions storming Pastrana.

Infantrymen scoured the town. No house was overlooked. The searchers worked in half-squad groups. Their first step was to surround the building; their next to scrutinize doors, windows, and thresholds for booby traps. Then two men would enter the house. They would poke from room to room, the second man covering the first. This is the “buddy system.” Grenades were tossed through windows of huts suspected of harboring Japs. Flamethrowers set some ablaze. But most houses were found abandoned. Most of the furniture the enemy had chopped up as firewood for his rice kitchens. Here and there a sniper was discovered. Then a brief fight ensued, followed by the search for “souvenirs.” And souvenirs ranged from battle flags to gold teeth.

That day the corpsmen were too busy to eat. One two-man team rendered first aid to more than thirty wounded. Aid Men Lawrukiewics of Kansas City, and Bill Lessard of Gary, Indiana, crawled thrice into zones swept by Japanese machine gun fire to patch up and carry wounded comrades out of the path of bullets. An emergency hospital they established in the local jail.

Stringing telephone wire from a forward observer’s nest to the regimental command post, two signal corps soldiers saw bullets chip the road under their feet. They dived into a ditch. The ditch was half filled with stagnant water. They heard more bullets bite into the rim of the ditch, and they heard the flat cracking of Japanese rifles in a bamboo thicket. One of the signal men was hit. The other, Pedro Echaves of San Diego, California, propped up his buddy’s head so that he would not drown in the muck. Then he dashed to the aid station for help. But the jail too, was under direct fire. The medics lay nailed to the ground.

“Hey, you guys,” said Echaves, “give me some morphine.”

He took the morphine and raced back to his wounded comrade in the ditch. He plunged into the ditch. The snipers fired. The wounded soldier moaned. “Here I come,” said Echaves. “Everything’ll be all right, Joe.” He injected the morphine. As the moaning man became quiet, Echaves hoisted him over his shoulder and carried him to the aid station at a run.

The man needed blood if his life was to be saved. But the sweating medics had used up the last plasma on hand in the forward lines. They sent an emergency call to a unit fighting at the other side of the town.

Soldiers entangled in a sniper skirmish saw a bulldozer rumble into town at top speed. Hunched atop the bulldozer were two helmeted young men. One was driving. The other sprayed slugs from a submachine gun. The lumbering contrivance was drawing fire from all sides. Infantrymen shouted at the driver to stop. An officer sprang from an alley attempting to wave the bulldozer to a halt; seconds later he leaped for his life. The driver roared,

“Get the hell out of my way.”

The officer roared back, “What the hell do you think you’re doing?”

The bulldozer tore past him, past the star-shaped fort, and on into the town square. It thundered abreast of a battalion headquarters, and then the man with the submachine gun leaned over and dropped a neatly wrapped package.

“Here is your bloody plasma,” he said.

With that, the bulldozer wheeled and clattered away and out of town. At the outskirts an enemy pillbox on the right opened fire. Bullets ricocheted from the bulldozer’s raised blade. The driver whistled as the bullets struck. He changed the course of his machine. He wallowed it off the road, lowered its blade and charged the pillbox. Two swipes of the blade covered the firing ports with earth. A short withdrawal, followed by a thrust, caved in the strongpoint’s side. A few more swipes of the blade buried the wreckage and its occupants. Then the bulldozer roared off as fast as it had come. Atop it the helmeted young men smoked cigarettes. (They were Technician Russel K. Herritz of Reedsburg, Wisconsin, and Private First Class Zack W. Landrum of Dumas, Texas.)

The seizure of Pastrana left the Japanese command disrupted and confused. Its main route of supply, reinforcement and escape was cut off. But there remained the twisted mountain trails which followed the cascading streams and the jungle-choked gorges east of Pastrana.

Nineteenth Infantry battle teams branched out to seize the trails and the mist-shrouded passes. The maneuver would secure the flank of the forces which then were sweeping northward in the broad valley below. Planes dropped bombs on stalled enemy columns near Bonga-Bonga, south of Pastrana. Zeroes took to the air on strafing missions, and from trails and ditches below foot troops watched the dogfights in the evening sky. The First Battalion pushed four thousand yards southwest to Macalpe to block a ford across the Binahaan River. The Second Battalion advanced upriver to Tingib Village, and there dug in for the night. And the Regiment’s Third Battalion, reinforced by the first hot meal since the Red Beach landings, patrolled with vigor around Pastrana.

Many things happened that night. The Japanese did not realize the extent of the regiment’s thrusts into the mountains. One Jap supply party carrying tinned fish and rice marched into an American perimeter. Enemy runners shot and killed along the trails were found to bear messages for extinct Japanese command posts. A lieutenant[1] leading a patrol over a twisting woodland trail saw three Japanese soldiers sound asleep in the shade of a banana grove. He decided to pounce on them and take them prisoner. The Japs screamed as they felt themselves seized roughly. Then a scout yelled, “This place is lousy with Japs!” The officer was startled to see the trail ahead come to life; it had been lined with sleeping Japs, and the Japs were waking up.

The prisoners scuttled into the bushes. The patrol opened fire. Both sides were utterly surprised. Not knowing that they outnumbered their attackers ten to one, the Japanese fled. They deserted their weapons and left six dead.

Later that night an enemy convoy of horse-drawn carts loaded with artillery ammunition approached a perimeter outpost. A Jap soldier walked up to the outpost. The outpost guard did nothing. He explained later, “The Nip looked just like a guy in my company.” Then the Nip pulled out a map and asked a question in Japanese. “What?” The Jap sensed that something was wrong. He vanished in the darkness and the guard fired.

The convoy could not turn on the muddy one-lane track. Machine guns and anti-tank cannon raked the hapless column. Teamsters and convoy escort dashed madly into an adjacent swamp. Carts were splintered and overturned. The cries of dying horses filled the night. Sixteen Japanese corpses were found among the carts. The trail was strewn with ammunition and with horses.

A sergeant from Connecticut could no longer endure the moaning of injured animals. He jumped out of his hole, Garand in hand. He wept as he strode along the path, shooting each horse between the eyes. “Jesus Christ,” he muttered, “the horses.” On his way back to the perimeter he found two Japs hiding in a smashed cart. He killed them both.

A night later— October 29— a column of Japanese approached the Pastrana perimeter openly and in single file. They were sauntering along as if they were promenading in a park in Tokyo. Outposts met them with canister fired from 37 millimeter cannon. All were killed but two. Toward morning a rummaging infantryman found the two survivors hiding under a bamboo shack. One of the two brandished a grenade. He was shot through the head before he could hurl it. The other gave himself up.

“Don’t shoot me, dear Americans,” was his unusual plea.

“Why did you say that?” a Division interrogator asked him later. “Don’t you want your divine spirit to continue to harass us?”

“No,” the Jap said. “I like America.”

“Why?”

“Oh, American movies.”

“Have you lived in America?”

“No, sir.”

“Where did you see the American movies?”

“The Japanese army shows American movies to Japanese soldiers,” the prisoner explained.

“Do you know of any more Japanese soldiers who want to surrender?”

“No, sir.”

“Do they believe that we will torture them?”

“Some believe so,” said the Jap. “Most believe that if they surrender, they can never return to Japan. They love Nippon. The people of Nippon will kill them if they return. In Japan a soldier is dead when he is captured. Nobody writes him. His mail is lost. To be killed by Americans is better than to be killed at home.”

‘Will you return to Japan after the war?”

“No,” the Jap said sadly. “I can never return.”

More questioning brought forth that this prisoner and his killed fellows were motor mechanics sent to get a number of trucks parked in Pastrana. They did not know that Americans had captured the town two days before.

Numerous skirmishes flared up between combat patrols roaming the mountain passes and Japanese detachments attempting to traverse the watershed. Eight Japanese charged with bayonets a force of two hundred Americans bivouacked near Hubas, south of Pastrana; every man in this suicide squad was riddled with bullets. Two Banzai night attacks were repulsed in the vicinity of Ypad. A Division combat patrol of sixty pushing to the headwaters of the Binahaan River encountered a hundred Japanese not far from the village of Riral. These Japs wore uniforms and helmets different from those worn by the Sixteenth Imperial Division, and they fought with ferocity and skill. The Americans were forced to fall back. But at dusk scouts spotted the enemy bivouac near Rizal. There were many little fires over which the Japanese cooked rice in their messkits. A sudden night artillery barrage killed most of the camped foe. They were never buried. The odor of rotting flesh lingered over the area for days.

Farthest into Leyte’s mountain wilderness pushed the men of Company “A.” They climbed the rugged slopes directly toward the enemy base of Ormoc. Their task was to block the old Spanish trail which links the mountain passes with Lake Danao. It was a nine-day mission.

Guerillas were enlisted as guides. The task force cleaved its way with machetes over nigh impassable trails. It forded many name less streams. The nights it spent in tangled underbrush and pouring rain. Through nine days and nights no man of this team wore a stitch of clothing that was dry. Supplies of food and ammunition were limited to what each man could carry on his back.

Toward evening of the first day the company struck a Japanese outpost on the approaches to a narrow pass. The Japs fired first. A Filipino scout fell wounded. A squad of infantry then flanked the outpost and attacked. Two enemies were killed, and the survivors fled into the jungle.

On the second day a column of two hundred Japanese attempting to cross the mountains from Ormoc was stopped and dispersed.

On the third day “Able” Company’s men cut their way three miles up a deep gorge toward Lake Danao. They dug in on a bluff within the canyon. Near midnight, during a blinding rain squall, the Japanese attacked. They broke into the perimeter with bayonets and grenades, but were repulsed. At dawn twelve enemy cadavers were found between the foxholes.

By evening of the fourth day the company dug in astride the old Spanish trail. Patrols encountered more Japanese outposts to the front and rear. Three Japs were killed and the remainder chased into the lowlands.

The days that followed were a nightmare of rain, of taking life, of fatigue and hunger. The country between Mount Mamban and Mount Alto is a rugged welter of gorges and jungles. When Japs were encountered — as often as not they were less than five yards off before they could be spotted. Rations were exhausted and ammunition was soaked by the rain. For four days the riflemen lived on taro roots, wild bananas and papaya. Nights in the mountain passes were bitterly cold; fever, poisonous centipedes and chilling mists added to the suffering.

At one point, as the company toiled over a steep defile, enemy machine guns fired from the top of a ridge forty yards away. Enemy snipers moved out on bluffs overlooking the trail. Bullets cut down an aid man who hastened forward to help a wounded soldier. Grenades were pitched from treetops. The bodies of the dead could not be recovered for burial. But the use of the old Spanish trail was denied to the foe.

Near two of the blocked passes the task force struck booby traps at crossings. There were trip wires attached to high explosive charges, and hand grenades hidden in bunches of bananas. The Japanese used laced jungle vines as warning devices. And there were snarls of land mines along the trails.

During a skirmish for a ridge flanking one of the passes a typhoon blew. Night was near. Trees were bent low by the storm. The bark of rifles and the rataplan of the machine guns submerged in the thunder of the heavens and the roaring wind. The jungle heaved. Rain followed in drumming cataracts.

Through inky darkness and the screeching storm a man’s voice shouted: “Let’s pull out of here!”

The company withdrew into a canyon on the bottom of which a “nose” jutted like some forgotten island. Here the men dug in to weather the night. Corpsmen bandaged the wounded. There was nothing to eat. The walls of the gorge reverberated with a strange and savage rumbling. Lightning was continuous. And suddenly a flash flood roared down the gorge. The soldiers huddled on the nose were on an island surrounded by a pounding surf. Through sheets of lightning they saw that the waters carried with them rocks and trees and the bodies of the dead.

At the start of its mission the company had drawn rations for 275 men. When it rejoined its regiment it had been reduced to a strength of 120.

(Continue to Chapter 9: Jaro Sunday)

______________________________________

[1] Lieutenant Charles W. Dyer of Montgomery, West Virginia.