Editor’s note: The following is extracted from The Southern Christmas Book, by Harnett T. Kane (published 1958).

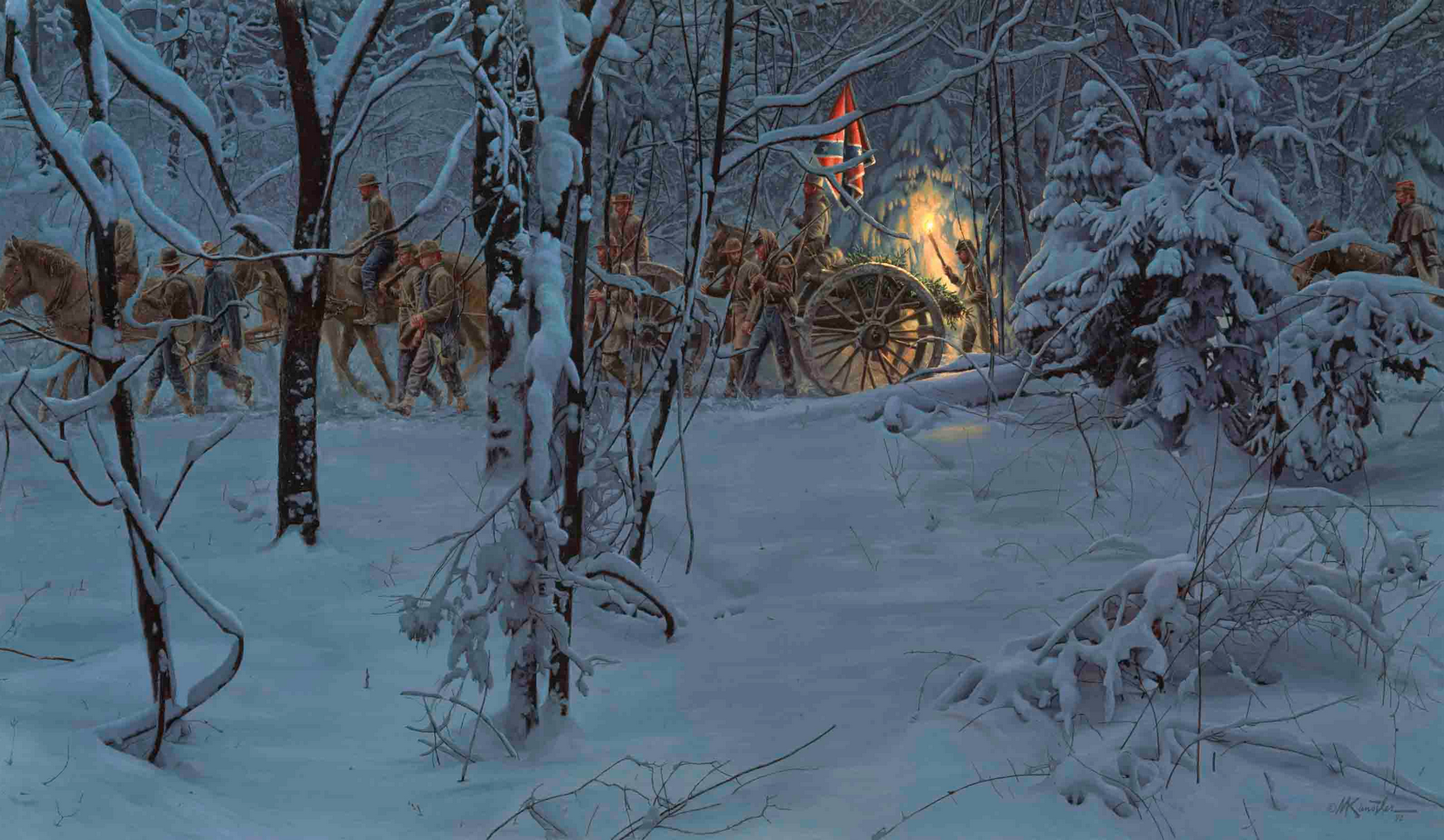

For four harsh years most Southerners approached the holidays with mixed feelings. Would the war never end? How would they be living — if, indeed, they were still alive — when Christmas came again? Some met the crisis with sacrifice and sustained courage, others with bitterness and tears. As do all wars, the Confederate conflict brought out the best in one, the worst in another, and although there were those whose speculations made the holocaust a period of huge profit and the display of garish luxuries, most of the people of the South lost steadily, month by month.

Hundreds of thousands greeted the December season with a sense of growing catastrophe, of the impending destruction of the life they had known. Whatever happened, things could never be the same again; whether or not they spoke of it, all of them accepted this fact. And each January 1, between the firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in 1861, and the May day of 1865 when Robert E. Lee sat sorrowfully opposite Ulysses S. Grant, Southerners asked themselves: Would the year ahead bring the military success they still hoped for, or would it be the end? The men could only struggle on, and the women could only scrimp and pray and try to “make do” with the meager supplies that remained to them.

Inevitably the war became a spiritual testing. With each Christmas soldiers knelt in prayer at the camps, or with their families and friends — if they had had the good fortune to be able to join them. Their wives and children also fell to their knees to ask God’s mercy and His protection. As the hostilities dragged on, a great revival of religion swept the South, and each Christmas saw crowded churches and lines of new converts in the armies.

Yet Christmas was not always a time of prayer. Many, alone and friendless at the “happy season” in Richmond or Atlanta or Mobile, took their fun where they could find it; and shocked Virginians and Marylanders, Georgians and Texans shook their heads at the reeling men who were observing the holidays in the company only of the bottle, or were shouting and fighting in the saloons and dives of the war-crowded cities.

Still others, affecting a cheerfulness they did not feel, went to work to lighten the holidays for those around them. A fortunate few had the gift of laughter, of a smiling composure between interludes of pain. For their wives or husbands or children, such individuals made Christmas seem almost the same joyous fete they had always had — with ersatz material.

As a boy I once listened to a white-bearded veteran at New Orleans describe a Christmas late in the war. “Son, nothing was what it looked like on the table. It was anything and everything else. But that didn’t matter too much. We had ourselves a time, anyhow. You can always manage if you want to.” Year after year, many Southerners at Christmas time tried to prove that they could “manage” in a variety of ways.

Few episodes I have heard of give so poignant a picture of innocent victims of the brothers’ war as one involving a group of people who settled in Arkansas during the decade before the conflict. A few years ago, W. J. Lemke of the University of Arkansas faculty drew upon the incident for a moving Christmas message to his former students.

In 1850 several German families arrived in the area to establish the settlement of Hermannsburg, known today as Dutch Mills. Frugal, energetic, they fixed the foundations of a good life with farms, a store, and a mill. Their leaders were the brothers John and Karl Hermann, who set their neighbors an example of hard and steady application. The new families got along well with those around them, but as the cloud of war slowly approached Arkansas difficulties arose. These Germans had a slave or two, but they were not members of the traditional planter group, and did not join in the furious talk that went on about them.

Whispers started: the Germans were Yankee lovers, abolitionists. Shaking their heads, the Germans said only that they were neutral, that they had no concern in the clashes between North and South. All they wanted was to be let alone to do their work and look after their families.

But their wish was not to be granted. After the war broke out, the settlers at Hermannsburg spent an uncertain Christmas sea son, and during the next months the situation grew steadily worse. Rival armies moved about the land, and raiders and “bushwhackers” swept down on scattered sections. The families at Hermannsburg received threats and warnings ; every week made it clearer that they and their children could not remain there in safety.

After long thought the Hermanns decided to go to St. Louis, where there were other Germans of whom they knew. As Mr. Lemke noted in his Christmas message, based on an original German volume, they would have to leave almost everything they owned and begin all over again, after twelve years in the place they had chosen and made their home. So be it…. Tearfully they made their plans.

General James F. Blount, the Union commander, provided a cavalry escort for them, and they started out just a week before Christmas of 1862. There were nineteen in the band, including eleven children, the youngest one year old, and even for the men the trip would be a hard one. They paused at Prairie Grove, continued on, and on December 24 arrived at Fayetteville, Arkansas. The little group spent the night before Christmas near a spring at one end of the village. As Nanni Hermann, wife of one of the two brothers, wrote in her diary: “Looking up at the star- studded sky on Christmas Eve, we saw once more in memory the lighted Christmas trees of our far-off fatherland.” Pathetically she added: “But the Christ child had lost its magic….” A shadow other than war passed over the party. Nanni Hermann did not survive the trials of the trip. She died before they reached St. Louis, leaving a two-year-old child and another of five, who had been born while she and her husband struggled to establish themselves in Arkansas. “The spot where these nineteen refugees spent their heartsick Christmas in 1862,” Mr. Lemke declared in his Christmas message, “is just across the street from the Lemke home.” He concluded:

On Christmas Eve I shall walk out in my back yard and look across the ravine. And I shall remember two mothers — Nanni Hermann with her babies, sleeping in a wagon bed in Fayetteville, and Mary with her baby, asleep in a stable in Bethlehem.

Another mother knew a grim Christmas in Virginia during the next year. Mrs. Roger Pryor, daughter of a minister who became a Confederate chaplain, and wife of a brigadier general, had served as a nurse at Richmond during the ominous Seven Days’ Battle. Now it was nearly time for her child to be born and she would have to be alone during this difficult period. Mrs. Pryor tried several times to get to her own family in Charlotte County, but the marauders and guerrillas who roamed the area made it impossible for her to reach them.

Therefore, with her two small boys, Mrs. Pryor went to her husband’s home town of Petersburg, hunting a place to board. General Pryor’s old friends had left, however, and all available quarters were crowded with refugees. For days she “wandered about,” until her funds fell so low that she became alarmed. At last she found a former overseer’s cabin outside Petersburg. It was in terrible condition — almost a hovel, with an unplastered, windowless kitchen, in which the ground showed through loose planks, and a single other room, curtainless, rugless, bitterly cold. Even so, it was better than nothing; and the officer’s wife and her sons started to work, clearing, rearranging the few sticks of furniture, bringing in wood to warm the place. A kindly woman neighbor, who lived some distance away, taught her expedients: “to float tea on the top of a cup of hot water would make it ‘go farther’ than steeped in the usual way”; “the herb, ‘life everlasting,’ which grew in the fields, would make excellent yeast, having somewhat the property of hops”; “the best substitute for coffee was not the dried cubes of sweet potatoes” (a source of wartime coffee for many Southerners), “but parched corn or parched meal, making a nourishing drink.”

The neighbor taught Mrs. Pryor other, more important things, too, appealing to her to cling to her hopes, stimulating her to “play her part with courage.” Daily the older woman sent over “a print of butter as large as a silver dollar, with two or three perfect biscuits, and sometimes a bowl of persimmons or stewed dried peaches. She had a cow, and churned every day, making her biscuits of the buttermilk, which was much too precious to drink.”

With Petersburg practically under siege, most foods were almost impossible to obtain. Markets had closed; the lone grocery had a stock that consisted mainly of molasses produced from sorghum cane, “acrid and unwholesome.” A grimy closet in the cabin yielded a left-over handful of meal and rice, and a small piece of bacon. Somehow Mrs. Pryor and her sons managed; the boys kindled fires in the open kitchen, roasted chestnuts, and set traps for rabbits and snowbirds, “which never entered them.”

Christmas was only a few days off when, after considerable effort, Mrs. Pryor finally found and hired a maid who could give her the woman’s care she required. Two days before the holy day a snowstorm swept down; with the time of Mrs. Pryor’s delivery very near, she remained in bed while the boys stayed cheerfully near her. “They made no murmur at the bare Christmas; they were loyal little fellows to their mother.” She spent the day mending their worn garments, since she lacked materials to make new ones for them. “The rosy cheeks at my fireside consoled me for my privations, and something within me proudly rebelled against weakness or complaining.”

At midnight, when the snowflakes were falling heavily, her labor pains began. The doctor lived three miles off; by the time he arrived Mrs. Pryor was suffering badly. “It doesn’t matter much for me, Doctor!” she whispered. “But my husband will be grateful if you keep me alive….”

When she wakened, the doctor was standing again at the foot of the bed, where she last remembered seeing him. Putting out her hand, she touched a small, warm form at her side, a girl. Gravely the doctor told her he had to leave and that he would not be able to return. “There are so many, so many sick.”

After a while Mrs. Pryor dozed off and woke with a feeling of strength and satisfaction. Then came another blow: on Christmas morning her maid left, because the cabin felt too lonesome.

For the next few weeks Mrs. Pryor cared for the baby herself, “sometimes fainting when the exertion was over.” Then one of her boys ran in, his voice showing his alarm: “An old gray soldier is coming! “

The gray man entered. “Is this the reward my country gives me?” he asked in a tightened voice. Only when she heard him did Mrs. Pryor recognize her husband. He had aged so much since their last meeting…. Now he called to an attendant: “Take those horses and sell them — sell them for anything. Get a cart and bring butter, eggs, everything you can find….”

All but one of his horses were sold; the money they brought Mrs. Pryor sewed at her waist. General Pryor was able to stay with his family until their situation was materially improved; once the crisis was over, he went back to the fighting. To the Pryors, Christmas of 1862 would long remain a hard memory.

The Christmas season of 1864 found another officer’s wife, Mrs. Fannie Beers, nursing the wounded at Lauderdale Springs, Mississippi. Born in the North, she had married young and moved to New Orleans with her husband. At the war’s start Mrs. Beers crossed the lines to be with her parents, but soon she returned to the South with her small son. Despite some complaints that she appeared too young, Mrs. Beers served as a hospital matron, working over a four-year period in Alabama, Georgia, and other states.

During the holiday period in ’64, hospital supplies fell very low and, she said, articles previously considered necessities had become “priceless luxuries.” Whenever eggs, butter, or chickens arrived, hospital workers hoarded them for the very sick, and understanding the situation, most of the other patients accepted it.

Shortly before Christmas Mrs. Beers discovered a newcomer, his head and face in bloody bandages. A fellow soldier, also injured, was breaking up corn bread with a stick in a tin cup of cold water. In reply to her questions the second man explained that his friend had been shot in the mouth and could swallow only soft food.

“I will bring him some mush and milk or chicken soup,” Mrs. Beers said firmly. The friend, well used to war shortages, stared with wide eyes. “Yer ga-assin’ now, ain’t ye?” Assuring him she was not “gassing,” the matron sent for broth, got it, and fed it, spoon by spoon, to the wounded man. As the other watched hungrily, Mrs. Beers asked: “Now what would you like?”

After some hesitation he replied: “Well, lady, I’ve been sort of hankerin’ after a sweet-potato pone, but I s’pose ye couldn’t noways get that?” She certainly would try; it would be a Christmas treat for all the patients. Granted an ambulance by the surgeon in charge, Mrs. Beers made a foraging expedition among the farmers and came back with potatoes, a few dozen eggs, and butter.

At her temporary home, a rudely constructed cabin, the driver advised her: “Them ‘taters has to be taken in out of the cold.” His meaning was clear; it would certainly not be best to offer temptation by leaving the sacks outside. That night, after she had gone to sleep, she was suddenly awakened by Tempe, her Negro helper, who ran screaming to her side: an earthquake had struck! Mrs. Beers heard a heavy banging and to her horror saw the floor boards lift and fall. Then one plank fell aside and up came the head of a hog, who, with his brothers, had been drawn to the scent, and had formed a raiding party. Mrs. Beers had been through bullet fire, she had nursed and tended the wounded and mutilated, she had survived many a hazard. But she had a “mortal fear” of live pork. Luckily Tempe suffered from no such terror, and, seizing a piece of burning wood from the fire, she ran to the intruder. Wedged in the narrow opening, he squealed piercingly as the girl yelled and beat at him. Neighbors knocked and the attack ended…. The Christmas treat of potato pone and a cup of sweet milk was a great success, and for most of the patients this was a happier meal than they had known in months.

It was a grim hour for all of the South when William Tecumseh Sherman, after marching relentlessly through Georgia, sent a wire to Abraham Lincoln at the end of that same year. “I beg to present to you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah with a hundred and fifty heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, also about 25,000 bales of cotton.” To many Georgians the words rankled almost as much as had Sherman’s fiery progress from the fallen Atlanta to the sea.

A young mother has caught much of the pathos of the hour in several brief entries in her diary. Dolly Sumner Lunt, from Maine, married a planter who lived near Covington, Georgia. Three years before the start of the war her husband died, and as Mrs. Thomas Burge, Dolly continued on the estate with her daughter “Sadai” or Sarah. The Burges were still there when Sherman’s men passed, and many of the plantation Negroes, afraid of the soldiers, slipped into the house to be with their mistress.

On Christmas Eve Mrs. Burge described her preparations for a bleak meal, her attempts to provide the plainest of presents for her remaining servants. “Now how changed!” she wrote. “No confectionery, cakes or pies can I have. We are all sad…. Christmas Eve, which has ever been gaily celebrated here, which has witnessed the popping of firecrackers and the hanging up of stockings, is an occasion now of sadness and gloom.” Worse, she had nothing to put in her Sadai’s stocking, “which hangs so invitingly for Santa Claus.”

On Christmas night Mrs. Burge penned a sorrowful after- note: “Sadai jumped out of bed very early this morning to feel in her stocking. She could not believe but that there would be something in it. Finding nothing, she crept back into bed, pulled the cover over her face, and I soon heard her sobbing.” A moment later the young Negroes had run in: “Christmas gift, Mist’ess! Christmas gift, Mist’ess!” Mrs. Burge drew the cover over her own face and wept beside her daughter.

The next year, Christmas came more happily to the Burge plantation. On December 24 the mother gave thanks to God for His goodness “in preserving my life and so much of my property.” And on Christmas Day she added:

Sadai woke very early and crept out of bed to her stocking. Seeing it well-filled, she soon had a light and eight little Negroes around her, gazing upon the treasures. Everything opened that could be divided was shared with them. ‘Tis the last Christmas, probably, that we shall be together, freedmen! Now you will, I trust, have your own homes, and be joyful under your own vine and fig tree….

Some, at least, of the freedmen stayed to work on the plantation, which, today, is still in the family’s hands.

For hundreds of thousands of Southern children there was tragedy in the non-appearance of Santa Claus during the later war years. Explanations were attempted: the Yankees had captured the old Saint this year. Or perhaps Santa had been caught in the blockade. In the journals were tales and poems designed to make the situation less gloomy for the young:

I’m sorry to write,

Our ports are blockaded, and Santa, tonight,

Will hardly get down here ; for if he should start,

The Yankees would get him unless he was “smart,”

They beat all the men in creation to run,

And if they could get him, they’d think it fine fun

To put him in prison, and steal the nice toys

He started to bring to our girls and boys.

But try not to mind it — tell over your jokes —

Be gay and be cheerful, like other good folks ;

For if you remember to be good and kind,

Old Santa next Christmas will bear it in mind.

In Richmond a hard-pressed family used ingenuity in providing decorations for its tree. During the cold spell just before Christmas, the few last hogs were killed, even though they were almost “nothing at all but skin and bones.” Lacking corn for feed, the family had let the animals shift for themselves in the woods and orchards. When the killing ended and the children looked for the usual ears and tails to roast, they discovered that these choice objects had — oddly enough — disappeared.

On Christmas Day the mystery was solved. Among the greens sat the missing pig tails, “curled up in the most comfortable manner and richly clothed in paper ruffles.” Nearby on the tree reappeared the pigs’ ears as candle holders, while bits of potatoes and carrots had been put to the same use. Later the vegetable bits were served for dinner, and the children grimaced at the taste of wood that remained in them.

General Lee himself went on one Christmas tree, and — as befitted his station — close to the peak. In January of 1865 Isabel Maury wrote a spirited note:

Saturday before Christmas we were all busy preparing a tree for the children; it was beautiful. On the top were two flags, our Confederate and our Battle Flag. Gen. Lee, bless his soul, was hung immediately below. My gift from Ma was a pearl pin and earrings — Puss had coral, beautiful, they are. We all united and gave her a point lace collar and cuffs. Of course we had egg-nog Christmas night, but no company…. Last Tuesday night Miss Nanny Dunlop made her debut — we were at her house. About three hundred invitations were circulated (verbal) ; you know we Confederates cannot afford cards….

Thursday we were invited to Dr. Deane’s but did not go. Today being New Year’s day, we had numerous calls, tho very unexpected to us…. My only objection is that the Yankees not only do it, but abuse the custom, and I want to do entirely different from them. We are a distinct and separate nation, and I wish our customs to be as distinct as we are.

Many believed as fervently as the writer of this letter that the South would win. Others, more sharply realistic, saw the shape of the future. In Richmond on New Year’s Day of 1864, the brisk, influential Mary Boykin Chesnut wrote: “God help my country! I think we are like the sailors who break into the spirits closet when they find out the ship must sink. There seems to be for the first time a resolute determination to enjoy the brief hour, and never look beyond the day.

“I now have no hope. ‘Have you any of old Mr. Chesnut’s brandy here still? It is a good thing never to look beyond the hour. Lawrence, take this key, look in such a place for the decanter market…’ etc.” As Christmas approached a year later in Columbia, South Carolina, Mrs. Chesnut declared in still greater gloom: “The deep waters are closing over us; and we in this house are like the outsiders at the time of the Flood. We eat, drink, laugh, dance, in lightness of heart!”

Another woman later remembered in clear detail the holiday season in the Confederate White House, in the last year of the war. Varina Howell Davis, Mississippi-born wife of the Southern President, declared: “That Christmas season was ushered in under the thickest clouds; every one felt the cataclysm which impended, but the rosy, expectant faces of our little children were a constant reminder that self-sacrifice must be the personal offering of each member of the family.”

Because of the expense involved in keeping them up, Mrs. Davis had recently sold her carriage and horses. A warm-spirited Confederate bought them back and sent them to her. Now she planned to dispose of one of her best satin dresses to obtain funds; with Christmas on the way, the children had high expectations, and she would use all possible makeshifts in an effort to fulfill them.

The Richmond housewives could find no currants, raisins, or other vital ingredients for old Virginia mincemeat pie. But, Mrs. Davis went on, the young considered at least one slice their right, “and the price of indigestion… a debt of honor due from them to the season’s exactions.” Despite the war, apple trees still bore fruit; with these as a base, she and the other women of the city would utilize any other fruit that came to hand. A little cider and some salt were obtained, as was brandy, though its usual price was a hundred dollars a bottle in inflated Confederate money.

As for eggnog, the Negro stable attendant, who brought in “the back log, our substitute for the Yule log,” said he did not know how they would “git along without no eggnogg. Ef it’s only a little wineglass.” After considerable effort, the eggs and other makings were found. Plans progressed for a quiet home Christmas when unexpected word arrived: The orphans at the Episcopal home had been promised a tree and toys, cake and candy, plus a good prize for the best-behaved girl, and something had to be done about that.

Something was done. With Mrs. Davis’s help, a committee of women was set up and the members repaired to their children’s old toy collections to salvage dolls without eyes, monkeys that had lost their squeak, three-legged and even two-legged horses. They fixed and painted everything, plumping out rag dolls and putting new faces on them, adding fresh tails to feathered chickens and parrots. Robert Brown, one of the house staff, volunteered to build a “sure enough house, with four rooms,” for the orphan’s prize.

The Davises invited a group of young friends on Christmas Eve to help make candle molds and string popcorn and apples for the tree; Mr. Pizzini, the confectioner, contributed simple candies. For cornucopias and other ornamentation the Davis guests used colored papers, bright pictures from old books, bits of silk foraged out of trunks. All in all, the Christmas Eve of 1864 was far from unsatisfactory. When the small supply of eggnog went around, the eldest Davis boy assured his father: “Now I just know this is Christmas.”

The next morning the Davises received their presents. For Mrs. Davis there were, among other things, six valuable cakes of soap, made from grease of a ham boiled for a family, and a pincushion stuffed with wool from the pet sheep of a farm woman. The family walked to St. Paul’s Church, to hear a sermon by Dr. Charles Minnegerode, the Christmas-tree pioneer whom we met in an earlier chapter. Dr. Minnegerode had entered the Episcopal church, to win high fame in his region.

After services the Davises had their dinner. For it the cook managed a turkey and roast beef, a spun-sugar hen, life sized, and a nest of eggs of blancmange. The dessert made them all feel, as one of the party said, “like our jackets were buttoned.” The children’s pièce de résistance, however, was still ahead — the great orphans’ tree. That night they went to the basement of St. Paul’s, where the Davises watched the many gradations of emotion “from joy to ecstasy.” To Mrs. Davis the evening was “worth two years of peaceful life,” the kind of life she had not known for a long, long time.

About the same time, at Petersburg, the Army of Northern Virginia was to receive, for what would be its final holiday dinner, a meal to which hundreds had contributed. “Lee’s Miserables,” as many civilians called the soldiers in fond admiration, were tired, weakened. For months they had been subsisting on their usual ration of a pint of corn meal, one or two ounces of bacon, and little or nothing more. In the judgment of Douglas Southall Freeman, this mainstay of the beleaguered South was “starving on its feet.” One veteran said simply that he was so hungry he “thanked God he had a backbone for his stomach to lean against.”

When the holiday season approached, Virginians planned a feast to let the Army of Northern Virginia know their gratitude and their sympathy for the long-suffering defenders. From all sides came hoarded treasures — hams, chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese, bacon, vegetables. As the Virginia Cavalcade declared, “Some gave of their abundance, but most people gave generously of their little.”

Provisions became available for an estimated 35,000 men. To cook such supplies called for skill, ingenuity, and perspiration; all of them were available in the big kitchens of Richmond’s Ballard House where, under the direction of a caterer, three hundred fowls or meats were baked every four hours. The food was placed in barrels and sent to the front for New Year’s Day.

Admittedly some did not get enough, amid confusion and delay. In most cases, however, the food did arrive at the front, where the men reached eagerly for it. They ate and ate and sighed in appreciation. But one group took little of the feast, following the example of their superior. A special barrel had gone to General Lee and his staff; it contained about a dozen turkeys which were placed on a board, the largest in the center.

For a moment the Confederate commander stared down at the fine display and touched the biggest bird with his sword. “This, then, is my turkey? I don’t know, gentlemen, what you are going to do with your turkeys, but I wish mine sent to the hospital at Petersburg….”

So saying, Robert E. Lee went to his horse and rode off. As one of the officers at the scene ended the story: “We looked at one another for a moment, and then without a word replaced the turkeys in the barrel and sent them to the hospital.”

For some soldiers there was disappointment. After waiting for many hours, one company received its supply — a sandwich for each man — two slices of bread and a minute sliver of ham. Several hungry soldiers asked: “Is that all?” A moment later, as one reported it, they felt ashamed. Finishing his sandwich, a corporal lighted his pipe and asked God to bless the women responsible for the day’s offering. “It was all they could do; it was all they had….”

Lots of onion cutting ninjas…

Thank you for sharing this/these stories, sir.

A blessed Merry Christmas to you and every man of good will! Christ, our Lord is born!