Editor’s note: The following comprises Chapter 6 of Children of Yesterday, by Jan Valtin (published 1946).

(Continued from Chapter 5: Church Bells Ring in Palo)

__________________________________________________________

The signal for the attack was to be the waving of a white handkerchief….

Some difficulty was experienced in finding a white handkerchief, but a search finally brought forth one still light grayish in color.”

(From the Division Record)

__________________________________________________________

His name is Fred Palmer, but before we finished with the hot jumble of hills between the beachhead and the Santa Fe Trail[1] we had dubbed him “Waterboy.” He has the neck and shoulders of a Greek god and the arms of a stevedore. His job is that of a first scout. A first scout, as everyone knows, is the man between whom and the waiting enemy lies nothing but no-man’s- land and his own alertness.

The platoon lay isolated on a flat-topped hill. It was kept down by enemy machine gun fire from higher ridges in front. Only sparse grass covered the plateau, which measured some two hundred yards from edge to edge. Steep slopes matted with high jungle grass fell off into brush-choked gullies three hundred feet below. A scourge of snipers hovered on the hillsides and in the shadowy ravines. From three sides sniper fire commanded every square yard of the plateau.

All night the platoon had been there, and most of the following day. For ten hours the men had gone without water. The sun blazed on their helmets. The steel became too hot to touch. Some men tried to chew grass, but their tongues felt swollen and numb. It was as if invisible hands shoved quantities of sand down unwilling throats. There was little ammunition left, and less food. But minds kept clawing at the thought of water— of a spoonful of water, of a shady pond, of rivulets and cataracts foaming from the mountains. Peculiar how a soldier’s thirst becomes as big as a house as soon as he knows that his canteen is empty. A man crawled fifty yards for a coconut and was killed. The nearest water was four hundred yards away.

“Hell,” said Fred Palmer, “I’ll go.”

Across the killing zone between the foxholes he crept, thrusting his hundred and ninety pounds of bone and muscle across the open ground, face low and the rim of his helmet scraping the grass. Bullets from a neighboring ridge slapped the earth five yards to his left. Palmer crawled on.

Someone bawled: “Get back in your damn hole, you’re draw ing fire.”

Palmer turned sideways. His face was dripping.

“Hand me your canteens,” he said.

“Christ, what a fool,” the others thought.

Palmer collected the canteens. Then he moved away, dragging with him the cluster of containers. The Japs saw him go and their bullets seared the grass. The platoon replied angrily to give Palmer a chance.

He crossed the plateau in short rushes. Then he hugged the ground, rolled a few yards to dodge the snipers’ shots, and lay still until the firing stopped. After that he jumped up again for another quick rush. The canteens rattled as he ran. Little fountains of dust danced upward inches from his feet, or so it looked. He reached the edge of the plateau and plunged down the slope and out of sight.

“Good guy— Palmer,” the others said, never expecting to see him again.

An hour later Palmer returned. The crackling of rifles on the hillside signaled his return. The platoon could hear his panting a hundred yards off. He crossed the fire-raked plateau at a dog-trot. No rushes this time. The platoon sprayed the slopes to keep the snipers down. Palmer kept coming.

“Waterboy! Waterboy!”

In a flat voice an officer said, “Magnificent.”

Past snipers’ nests, up three hundred feet of rough hillside, across two hundred yards of death-ridden open terrain, and under a graceless sun, Palmer brought on ten gallons of water, one case of grenades and two cases of rifle ammunition.

There was another soldier who said “I’ll go,” when the going was really tough in the hills around Palo. None of us will ever forget how he quietly gave up his life to save the life of his squad. His name was Wilber and he came from Maine. He was the type who liked to dream in the shade over a can of beer.

The squad had pushed ahead of the line and ran into trouble. There was a steep crest above them and below them was a reeking swamp. Jap machine guns jabbered from hidden dugouts and bullets whipped through the brush. And when the jabber ceased, counter-attack began. Three times in succession they tried to overrun the squad. Some came like cats. Others ran in shouting, grenade-heaving packs.

The squad lay in shallow trenches and fired. With them was Wilber. A mass migration of ants traversed the rottenness under the thickets. Ants crawled into the rifle sights, into the sleeves and over the faces of the men. One man groaned, clawing at a fragment of grenade in his neck; another died, a bullet through his mouth. After the third attack had been thrown back, the squad leader said, “Check ammunition.”

Voices: “Three rounds.”

“All broke.”

“Two clips.”

A cry: “Aid man— aid man.”

Between bursts from a machine gun a Jap voice yelled, “Charlie, how are you? Oh, Charlie, you listen? By-and-by we kill you. Don’t worry, Charlie.”

No aid man, no grenades, and ammunition running low. The squad leader looted the belts of the corpses. He evenly distributed their meager yield. “Redistribution of ammunition.” That’s what the Field Manual on Infantry Tactics said. Four rounds for each man in addition to the rounds in his receiver. Wilber pulled back the bolt of his Garand. One cartridge in the chamber, one left in the clip. No more.

“I’ll go,” he said.

He tossed his two cartridges to the man nearest to him in the skirmish line. The other took the ammunition without thanks. The man from Maine rolled out of his slit trench and away, then darted off crabwise on hands and toes. The strike of Jap bullets marked his course along the edge of the swamp. He was on his feet now. Bent low, he ran, his face almost touching his knees. A bullet slugged his helmet, glanced. Wilber went into a somersault. Then he ran on, bareheaded, and the others waited.

Nine minutes passed. The squad was silent. Watchful, scared and glum. There was a rustling in the undergrowth up the slope, but no one fired. No one said, “Please God, let Wilber come back before they attack.”

He came. Crouched low he was running along the rim of the swamp, and then he veered to scramble up the incline. He was going slower now, straddle-legged and heavy, like a woman with child. Bandoleers of ammunition dangled from his arms. More bandoleers hung round his neck.

The squad saw him. The enemy saw him, too. He hunched his shoulders for the last desperate spurt.

“Atta boy!”

Up on the crest a machine gun coughed. Wilber fell. He cried out and then he died. But someone crawled over and got the bandoleers.

The hills fringing the coastal plain of Leyte Gulf had twofold importance for the Japanese defenders of the Philippines. They were an excellent base from which to conduct forays into the beachhead and the town of Palo; and they were natural bastions flanking the highway into the Leyte Valley. Troops of the 16th Japanese Division, the one-time conquerors of Bataan, were told to hold these hills until General Yamashita could receive reinforcements from Mindanao and Luzon. Hold on they did through five bitter days.

The maps showed three hills: Hill 522, Hill “Baker” and Hill “Charlie.” But the maps were wrong. “Baker” and “Charlie” turned out to be not simple hills, but massive heights topped by a jumble of ridges and knobs not discernible from the beach. Where the map showed blank spots, infantrymen found walls of jungle, thickets of head-high kunai grass, boulders and bushy snipers’ roosts blanketing back-breaking inclines. Among the new discoveries were “Hill Baker One,” “Hill Nan,” “Baker’s Pimple,” “Hill 85,” “Hill Mike,” and “Hill 331” whose ridges spread like the fingers of an enormous hand. The storming of each cost agony and lives.

On Hill 522 the men of Colonel Zierath’s battalion went without sleep and food for several days. The tunnels through the rock beneath their feet were full of Japs. Pillboxes silenced in the initial assault on the crest persisted in coming back to life. Japs crawled back into the wreckage during the night and resumed the fight at dawn. Captain William Herman of “Baker” Company called for artillery fire to smash the strongpoints anew. Then infantry attacked with TNT and cold steel. Fifty Japanese were killed and the remainder were driven into the Palo River.

Weary of being hungry and marooned on Hill 522, Private Angelo Mantini of Kittanning, Pennsylvania, a shoemaker in civilian life, scurried toward Red Beach in quest of food. Half way down the hill he discovered five snipers who had ambushed a carrying party. Mantini decided that no Nip should prevent him from filling his belly. He killed all five and loaded himself with their weapons. Among the captured weapons was an American automatic rifle. Five minutes earlier, the Division commander, General Irving, had passed the scene of the encounter. The snipers, intent on wiping out the carrying detail, had let the general pass unscathed.

Another soldier set out to capture a Samurai sword. In inky darkness he blundered into an ambush and then lost his way in a swamp. Japs were all around him. For twenty-four hours the soldier played at being dead. American mortar shells plastering the enemy hideouts burst dangerously close to the man who played ‘possum. A fragment hit him in the arm. He buried himself in the mire up to his face. But the mortar bursts continued to creep toward him. “It’d be hell for Aldia if she ever learned I died that way,” the soldier thought. “If I have to get killed, let it be a Jap.” He wept and prayed. He floundered out of the swamp and ran. Japanese machine gun slugs pierced both his legs. But his comrades found him, and as he was carried to the rear, a young soldier, grimy and taciturn, stepped up and laid a Jap saber on the wounded man’s stretcher.

The enemy on Hill 522 had many automatic weapons. Eight heavy machine guns were captured there, and four mortars, but most of their weapons the Japanese had dragged into the tunnels. For days on end a grim drama was enacted at the tunnel entrances. Flame-throwers burned out many a holed-up Jap. A favorite method of tackling the tunnels was to cover up the vents and air shafts, then toss phosphorous grenades into the tunnels. The scorched and choked defenders dashed out into broad daylight. Infantrymen stationed above the tunnel mouths mowed them down.

Each night, when our infantry sat tight and silent, it was the enemy’s turn to attack. The Japanese slipped out of the tunnels. Here and there an American was killed by the screaming, grenade-throwing bands. On one occasion fourteen Japs attacked two hundred riflemen; the halloo of such lunacy stopped only after the last of the Banzai-men had been killed. Later that same night thirteen Japanese charged like hooting revelers, firing machine guns and brandishing spears and clubs. They, too, were killed. Then eight other Japanese advanced in single file behind a light machine gun, swaying and chanting as they came. All eight were killed, and other Japs dragged the cadavers into the tunnels. “Dammit, when do we sleep?” asked the irate men in the platoons.

The tunnels of Hill 522 were finally silenced on the sixth day. Their entrances were blasted down with dynamite and blocked with boulders and logs. The inmates of the tunnels were left to commit suicide or to starve. Sounds of eerie ceremonies filtered from the bowels of the volcanic height. The Japanese who dies for his remote Emperor earns a place in the Yasukuni Shrine and is promoted one rank; if the battle is deemed important, he is promoted two ranks, provided he is dead. No Japanese prisoners were taken. Jap wounded were killed.

“Now we sleep,” the infantrymen growled.

They were mistaken. It is difficult to judge the size of an attack in the dark. When nerves are taut the rustling of a hog or monkey in the sword grass is enough to make every man on the perimeter blaze away, and every man is awake. This last night four Japanese penetrated the battalion defenses and suddenly charged the command post. Guards killed three of them, and the lone survivor scuttled off into the night and was never found.

The fight for the precipitous ridges of Hill 331 was a different matter. No race to the top here, but a slow, dogged ascent, first through vile jungles, then through kunai grass, and finally through a maze of rocks. Trails were crooked and as steep as chicken ladders. At hardly any point was the visibility more than ten feet through green confusion. When you saw a Jap you were already atop of him— or he atop of you.[2]

The attacking force left the beachhead shortly after noon of October 21. It crossed a swamp, then toiled uphill through a welter of underbrush. Scouts in the lead heard a clicking sound in a nearby thicket. Instantly they dropped to the ground. They signaled the company to a halt. They crawled out to the flanks, and what they saw was a Japanese machine gun ambush. The gun’s muzzle pointed down a stretch of trail bordered by a palisade of bamboo so dense that it would have defied a hacking machete. The scouts fired, pumping ten bullets into the two Jap gunners. The ambush, had it not been discovered, would have cost many American lives.

A few minutes later the scouts halted again. Their rifles pointed toward a group of tumbledown nipa huts in a small clearing. The gesture meant, “Suspicious location.”

Sergeant Kenneth Allen of Denver, Colorado, led a patrol to investigate. As they approached the clearing the huts spat fire and the patrol was pinned down. Alone the Coloradoan rushed past the huts with rebel yells, heaving phosphorus grenades through windows. The huts went up in smoke and flame. Japs were seen running into the jungle, their uniforms afire.

The task force now approached the crest of the first ridge. At this point several hundred Japanese who had lain on the reverse slope went into action. They mounted machine guns behind boulders and sprayed the trail and the forward slope. From treetops came the crack of snipers’ rifles. Other Japs diligently rolled explosives down the cliff-like face of the hill. Whole squads appeared from nowhere and dropped grenades onto the skirmishers below them. Fire from Garands had no effect on the Japanese. It was like shooting at airplanes behind clouds of basalt. American grenades failed to clear the crest and rolled down upon the grenadiers as soon as they hit the ground. By 3 p.m. there were many killed and wounded. Some squads had been thrown off the upper hillsides. Whole platoons lay under murderous fire, unable to budge.

A man from the Bronx, Sergeant Louis Farber, led his squad to the top of the crest. He suddenly found himself in the path of a machine gun firing at arm’s length. Four men of his squad crumpled under the blow. Farber pounced on the machine gun. The most violent moments in all the hateful violence of war are those of close combat. Farber slew four Japs in hand-to-hand combat. There followed an exchange of rapid fire across a rock not larger than a steamer trunk. Farber still fired as bullets ripped into him and through him. He died fighting.

At another spot along the ridge Joe Bartnichak, who hailed from Passaic, New Jersey, leaped among a squad of Japanese grenadiers. There was a flutter of screams. Then three Japs pounced on Joe. Bartnichak smashed the butt of his Garand into the face of one, then kicked him over a cliff. He seized the bayonet of his second assailant and killed him with little more than his bare hands. The third Jap, who had been stripped almost naked in the fray, grabbed a fallen rifle; He thrust the muzzle against Bartnichak’s body and fired. Joe, too, died so that America might live.

By 3:30 p.m. the task force’s predicament had become so untenable that a retreat was ordered under cover of a mortar barrage. It was the first repulse of an American attack in the Battle of the Philippines. But minutes after the first mortar shells fell on the ridge, the Japanese countered with mortar fire of their own. When the Americans’ ammunition ran low before the withdrawal had been completed, Sergeant Howard Ritchie of Carlisle, Kentucky, risked his life to bring on more ammunition. He brought enough rounds to kill a Banzai party of thirty. But in a later phase of the battle the ping of a bullet coming from a clump of brush close by caused the sergeant to rise to his knees to locate the sniper. The sniper’s second bullet killed the gallant Kentuckyman.

There were some who cringed, and some who cracked, and there were others who challenged death to protect their comrades’ retreat from almost certain annihilation. Their names are the names of the best that is in America: John Pergzola of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who saw a heavy machine gun abandoned atop the ridge in the withdrawal and who crawled up and brought it back through snipers’ nests; Anthony Lego of Durand, Illinois, who held the Japs at bay with his automatic rifle until the last man of his platoon had slipped downhill to safety; Sergeant Louis Paul of Louisville, Kentucky, whose hand was smashed by an enemy bullet but who nevertheless continued to direct his squad; Sergeant Bill Pinyon of Blue Diamond, Kentucky, who, wounded and on his way to the rear, protected the other wounded by killing snipers who waylaid the evacuation party; Sioux Private Blue Horse who refused to retreat until he had fired his last cartridge into the face of grenade-rolling Japs.

And there was that intrepid group of advanced artillery observers who calmly remained forward to spot the details of the Jap bastion for their Division’s cannoneers. As the infantry disengaged, it passed the observers’ party, and after withdrawing another four hundred yards the riflemen dug in for the night. The artillery spotters stayed, and the enemy was half as far away as were their own lines.

The four observers set up a radio while bullets from heavy Japanese machine guns cut the earth about them. They remained forward until they had completed the adjustment of artillery. Then, working together, they disassembled the radio, collected all their equipment, and in a cool, orderly manner, withdrew.

A day later the riflemen attacked once more, this time in a torrential rain, and paced by the rolling thunder of an artillery barrage. Everywhere men slipped and fell on the mudbound incline. But led by Colonel “Red” Newman their assault carried the ridges of Hill 331 at the waving of a handkerchief “still light grayish in color.” Aerial observers reported many Japanese working their way westward through the jungle in the direction of the Leyte Valley.

Elsewhere around the beachhead and embattled Palo, other fighting teams of the Division assaulted other hills. Colonel Spragins’ battalion,[3] which had just weathered a night of Japanese charges into Palo, pulled out of town in the early afternoon of October 22 to drive to the summit of “Hill Baker.” The infan trymen leaving Palo resembled a host of gaunt and disgusted ghosts, unshaven, wet and dirty after two hard nights. Hill Baker, they found, was not one hill but three or four. Each was steeper and higher than the preceding one. All were fringed by dense woods, their upper reaches covered with jungle grass, and their summits topped by naked rock.

The battalion stormed “Hill Baker One.” On their way to the next hump in the hill mass they were stopped. Snipers fired from scores of foxholes dug into the slope. From treetops obscene in their bushiness machine guns fired. Some three hundred Japanese came charging around a shoulder of the height and in a pitched battle more than a hundred of them were killed. Americans, too, were killed, but never do men become accustomed to the filthy brutality of death in the jungle. Each time one falls it is horror resurrected; a gasp of fear and surprise, a cry, a rattle mingled with blood, a heaving and thrashing in the thicket, a convulsion of abysmal futility, and insects crawling toward the smell of death. Seldom is dying easy. Each soldier thinks: folks at home will never know how it is— one moment you’re alive and strong, a moment later you are a goddamned mess.

A medical aid man six feet away from Colonel Spragins was hit. Japanese were near, shooting and pitching grenades. The colonel’s carbine barked like a dog protecting the hurt medic Then, again a few feet away, the battalion intelligence officer was mortally wounded. The same bullet ripped through the colonel’s arm. The colonel felt the pain and he felt the warm stickiness of his blood and he controlled himself and pretended that he was all right. As long as Spragins fought his men would fight as well. It was his second bullet wound in as many days. He inserted a fresh magazine into his carbine and summoned two soldiers near by. Together the trio stood up and put shot after shot into the enemy counter-charge until the wounded aid man and the dying officer had been carried to the rear.

The battalion gave ground and spent the night atop Hill Baker One. The evening sky was a wondrous riot of colors. The ocean gleamed silver and crimson against the setting sun. The riflemen scraped out shallow holes and said “Hell” and “Shit” and worse, meaning the war, the Philippines, the Filipinos, their own officers and the mosquitoes.

On the morning of October 23, the First Battalion of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment set out to capture “Hill Charlie.” Guerillas had reported three hundred Japanese entrenched on the crests. The Japs had rounded up two hundred natives during the night whom they had herded to the hilltop as hostages against American shellfire and bombs.

About Hill Charlie, too, the maps were wrong. The wooded slope ended in an abrupt precipice not visible from the coastal flats, and beyond it there appeared two separate heights which were dubbed “Mike” and “Nan.” The battalion began by tackling Hill Nan.

Again, as on Hill 331, Nippon’s fighting men resorted to a skilful “rear slope defense.” They waited in prepared positions on the far side of the crest, out of reach of direct fire. They permitted the attacking platoons to advance to within grenade range of the summit. At this stage the Japanese rushed to the crest, manned concealed machine guns and dropped a shower of grenades on the Americans below.

Three times our assault waves attained the crest; three times they were repulsed. Again the sun dipped low and the sea and the jungle glowed with hushed splendor. At 1800 that day this battalion too, was ordered to retreat so that artillery fire could be put on Hill Nan, civilian hostages or no.

Each platoon left one squad on top to cover the retreat. The enemy sensed the situation and counter-attacked immediately to turn withdrawal into rout and annihilation. With a mounting crescendo of screams the yellow men drove over the crest.

Protecting the retreat was machine gunner Therwin Schneider of Pittsburg, Kansas. When the Japs swarmed up and around, too close to be reached by the machine gun’s traverse, Schneider half rose and hurled grenades. Somewhat down the slope a lieutenant and another sergeant[4] heard the din of the counter-attack. They quickly understood the seriousness of the situation. They grasped a sack full of grenades and back to the crest they rushed. There, they tossed grenades down the rear incline as fast as they could yank out the safety pins and pitch. Their rampage delayed the enemy thrust until their unit had safely disengaged. To boot, they dragged two wounded comrades to the rear.

Simultaneous with the struggle for Hill Nan, Hill Baker erupted again with the clangor of battle. Colonel Spragins’ infantry advanced in the wake of a rolling wave of artillery fire.

This time they overran a score of snipers’ nests and gained what they thought was the top of the hill. But then there appeared a “pimple” about one hundred feet higher, well fortified and manned.

Twice waves of riflemen charged the Pimple but were hurled back. They resorted to mortar fire, but mortar shells failed to make inroads on the caves and rock emplacements. Jap and American positions were too close together for artillery to pound the Pimple with success. It was tried at first. It was stopped when a shell fell into the battalion aid station and killed a soldier. After a day of sweaty and fruitless encounters the task force dug in for the night on the slope of Hill Baker. A Kentuckyman named James Allen saw a group of Japs draw up a heavy field piece from a valley a thousand yards away. The thought of having this cannon pound the perimeter through the night was disturbing. So Allen dragged a heavy machine gun across seventy-five yards of fire-swept terrain. He mounted it on a bald little knoll and put gunfire on the distant cannon until it was abandoned by its crew.

Begrimed and dead-weary, the men ate biscuits and cold hash in the dark. For a few hours that night in each three-man foxhole two men slept, oblivious of the flares, the grenades and the scattered volleys unleashed by the perimeter guards. Mosquitoes whined, men muttered in their sleep and bats sailed overhead. Artillery pounded the hills, slaughtering native women and children along with the Japs. The enemy raided the town of Palo that night, and shortly before dawn a Banzai charge swooped down from Hill Nan.

October 24 saw no decision in the commotion of the hills. Elements of Colonel Zierath’s battalion stormed Hill 85. Infantry assault teams seized Hills Nan and Mike. But the Japanese on Hill Charlie held on with vigor. And on Hill Baker, Spragins’ force by-passed the Pimple and fought its way to what was thought to be the true crest of the stubborn massif— but found a higher, steeper crest a few hundred yards to the west. There seemed to be no end to this much-cursed hill.

October 25 brought the decision. It also brought rain. Masses of water flooded the roads and turned jungles into quagmire. Rifles were covered with rust. Few experiences are more desolate than a breakfast of beans and pork gulped in haste in a water-filled mud-hole, with rain lashing the earth, and the day ahead a promise of misery and pain.

The battalions crossed a swamp, forded two streams, and attacked Hill Charlie shortly after dawn. The Japanese again employed their crafty “reverse slope defense.” All afternoon the battle blazed in mud and torrents from the skies. At 5 p.m. two companies dug in on top of the ridge. Through the night the infantrymen sat in holes up to their necks in water.

Meanwhile, another branch of this force assaulted a height on the northeast rim of the “Charlie massif.” This attack team encountered trouble because the enemy did not do the expected.

“The hill,” explains a field report, “and an open area in front of it were covered with tall kunai grass which thinned out and became shorter near the top of the hill, while the crest itself was covered with boulders and trees offering excellent concealment to the enemy.

“The men, familiar now with Japanese tactics of reverse slope defense, advanced boldly, feeling that they would have little opposition before reaching the top. When leading scouts were still a considerable distance from the crest, however, the enemy suddenly began a well-coordinated fire with rifles, machine guns and grenades.

“The company sought cover in the grass and returned the fire, but with little effect. Light machine guns were put into position on the hillside, but the slope was too steep, and they also were ineffective against the entrenched enemy. The company held on desperately until ordered to disengage at 1300.”

While the infantry fell back, artillery observers pushed forward up the hillside. They crawled through the grass on hands and knees, through the withdrawing lines, and onto the edge of the expanse of boulders. A radioman from Iowa City, Bert Hughes, set up a radio behind a rock. Soon the long steel arm of Division artillery on Red Beach reached over onto the enemy bastions. Hughes heard the shells wail overhead. He noted the location of their impact and corrected the artillery’s range by radio.

The Japanese spotted the observer. They sent snipers around to his right and left to wipe him out. Hughes felt quite naked now. He operated his radio in full view of the enemy. Bullets chipped his boulder. “OK,” he radioed. “Fire for effect. Over. Out.” With that he darted away and downhill.

The cannonade lasted two hours. Then the task force attacked once more through mire and downpour, and this time Charlie Hill was seized for once and all….

There remained Hill Baker, the last high ground which barred the way into the Leyte Valley. All through the night artillery had pounded the jumble of ridges. Colonel Spragins’ battalion slogged forward and uphill through drenching rain. It was difficult to believe that any Japanese up there could have survived the all-night barrage. Yet the Japs were there and they fought like self-confident ruffians. They gave battle from covered emplacements more than six feet deep and connected by tunnels. For observation they used a system of periscopes. From the crest of the Pimple sheets of fire slashed through the rain. It was the messiest, most brutal fighting Spragins’ riflemen had experienced up to that time. The best the companies could do was to cling to their ledge of mud and blood and dripping thickets.

By then it was 5:30 p.m. The heavens darkened with twilight. The night was like a giant anus. Time to dig in. A hasty perimeter was established. The men opened ration cans in the darkness. Exhausted from six days of almost continuous exertion they ate the dreariest supper of their lives. Rain fell without abatement. Colonel Spragins decided to do the unheard of, the utterly unexpected. He decided to resume the attack and close in for a kill in the dark.

‘Too hazardous,” his officers protested.

Their argument was sound enough. The men were dog-tired. Ammunition was low. Morale was low. Several battalion officers had fallen dead that day. The night was like an abyss of India ink and full of falling water. The terrain ahead was uncertain, unmapped, one great, menacing trap. In a night fight troops would become scattered. Men would lose their way in the dark and shoot at one another.

The colonel was adamant. Soaked, red-eyed, twice wounded, he stood in the rain and said:

“Alert the men. We pull out in ten minutes.”

Was Spragins playing a hunch? Was it a hunch? Glumly the squads and platoons stood in the rain. Rain pattered on their helmets and squashed underfoot. The butts of their rifles were held up to prevent the barrels from filling with water. They stood in dejected silence, too tired to grumble.

“All set? Get moving.”

Spragins led the way through the night. He picked a course by compass. The formations followed in single file, close so as not to lose contact with the men in front. The still column crossed a thousand yards of rough terrain and not a shot was fired. Toward midnight they reached the final crest of the hill. They stumbled upon a Japanese observation post. A network of fortifications surrounded the O.P. The stillness was ghostly. There was the breathing of many tired men and the monotonous melody of rain falling on leaves and corpses. The enemy strongpoints were unmanned. The emplacements were stocked with enemy equipment; there were kettles which contained leftovers of rice; but not a Jap was in sight. The Japanese, knowing that it was a rule of the Americans to halt all movement at dark, had gone off to spend the night in the shelter of native barrios. They had departed with the obvious intention of re-manning their bastions before dawn. The battalion’s night march caught them sleeping— away from their defenses.

“Dig in,” said Spragins.

Not many dug. The men flopped into the Jap trenches and lay still.

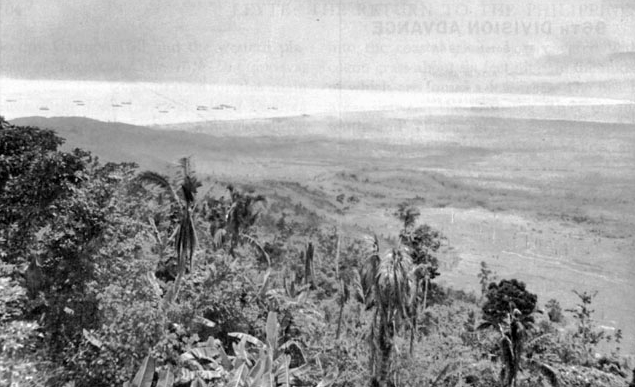

The rain stopped toward morning. Emerging from their beds of mud the men saw below them a broad and unobstructed valley, many towns, and a highway leading northwest: Leyte Valley and the Santa Fe Trail.

To their rear, between the captured massif and Red Beach, 1,928 killed Japs lay buried, and many more sprawled dead under the lid of jungle and swamp. The Division counted six hundred and thirty-eight wounded, missing, or dead among its own.

(Continue to Chapter 7: The Mainit River Bridge)

__________________________________________________

[1] Soldiers dubbed the main highway leading through Leyte Valley the “Santa Fe Trail” because of the town of Santa Fe which is located along this road.

[2] The assault on the hill mass known as “Hill 331” was consummated by the First and Second Battalions of the 34th Infantry Regiment.

[3] Second Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment.

[4] Lieutenant Clarence E. Weigel of Hays, Kansas, and Staff Sergeant Matthew J. Ott of Camden, New Jersey.