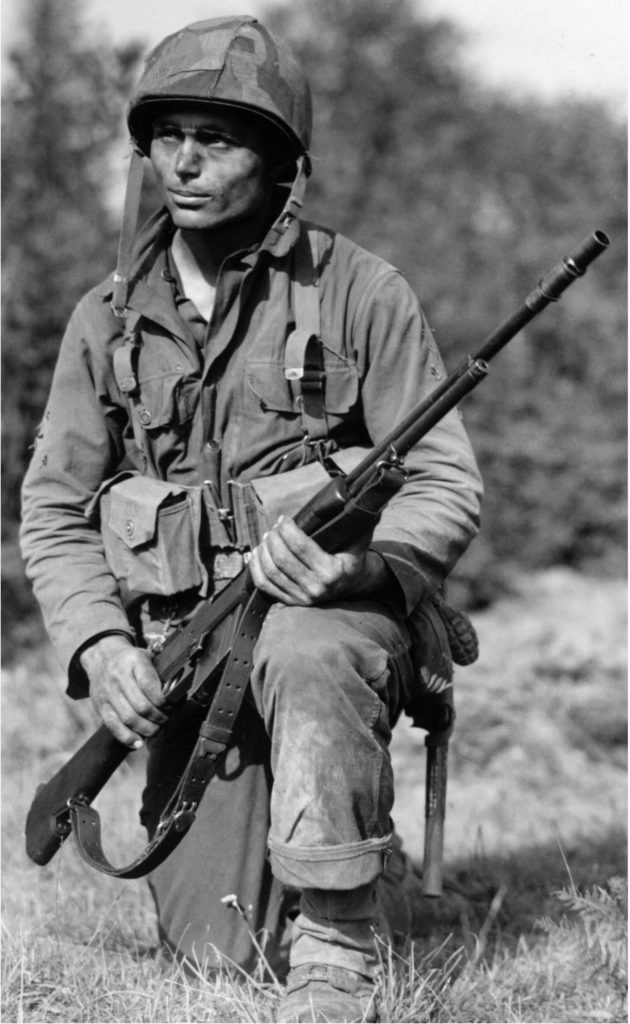

Editor’s note: The following article by David J. Daze is extracted from Infantry, Volume 78, Number 1 (January-February 1988).

Since World War II when I served in combat, many publications have done a magnificent job of bringing professional expertise to the modern soldier, but few have given ideas for individual survival. And as most of us have heard, if a new replacement can last one week in combat, he will probably survive many more.

I would like to offer here some good solid tips that either saved my life in combat or cost the life of someone around me when he neglected to follow them. Fortunately, I had read about and practiced many of these techniques before going to combat, and I am convinced that I wouldn’t be here to write about them if I had not done so:

Learn how to shoot left-handed. If you are going around a corner in either direction, you can always have your weapon go before you. That split second will give you an advantage if the enemy sees you at the same time you see him. Furthermore, you can shoot with either hand while keeping your body behind an obstacle— a house, wall, or tree. (Naturally, if you’re left-handed, learn how to shoot right-handed.)

Practice walking quietly. While trying to make a silent approach or on a night patrol, put the ball of your foot down first, or walk flat-footed. Normal walking with heels first will snap twigs, crunch gravel, and the like. A pair of socks pulled over your boots is even better. (Every company should have some extra large, heavy socks for night patrolling.)

When you go on a patrol, never return by the same route. Many a good man who slipped through an enemy outpost on the way into an area was ambushed coming out. By using another route, you can also cover more ground for surveillance. (Going through a path in a minefield is the exception to the rule, of course.) Be sure the men in your unit know you are out on patrol and from what area you will be returning. Green soldiers, in particular, are apt to be trigger-happy. Before going out, always check on your own minefields, claymores, and the like.

When attacking a room in a building, go in as low to the floor as possible. The enemy, especially if he’s surprised, will usually fire chest high or higher. Never stand in a doorway blasting the interior with automatic fire.

Always be aware of the immediate terrain. Any little fold of ground, especially in a flat field or desert, may save your life during a mortar or artillery barrage. Practice getting on your stomach and melting into the ground. Even a slight dip will make you far less vulnerable.

When approaching a new area, put yourself in the place of the enemy. Ask yourself where you would hide if you were him; where you would set up your machine guns; what fields of fire you would sweep; where you would lay mines, zero in your artillery, cover with riflemen; and where the blind spots are.

Watch the old pros in a combat-wise outfit. Many rookies are not so much afraid of the enemy as they are afraid of looking “chicken.” Accordingly, for fear of looking foolish, they won’t hit the ground fast enough or crouch low enough.

Never walk on a ridgeline or the crest of a hill. Stay just below the crest so that you are not silhouetted for an enemy observer who might otherwise never see you. When going over a crest, try to find a saddle or a clump of trees.

When resting or waiting, stay in the shadows if possible. This will prevent observation or sudden strafing by an aircraft. Deep shadows make excellent temporary camouflage, especially for vehicles.

Use all your senses! Obviously, vision is most vital, but hearing is important as well, especially at night. Your nose, too, can be a lifesaver. On three different occasions I smelled hiding Germans, who had the distinctive odor of the cheese ration they ate. No matter what they eat, soldiers get pretty “ripe” after a few weeks without bathing, and you can also sniff for diesel fuel, cooking food, cigarettes, and various other things.

Do not use a house or a village as a fort. Either can turn out to be a death trap. The windows give poor fields of fire, and one hand grenade or rocket thrown in can wipe out the unit inside. Use houses for warming centers, command posts, or brief respites, but no more than 20 percent of your men should ever be in a house or village at one time. The others should be dug in around the buildings whether awake or asleep. Many a command has been wiped out because almost everyone was inside a structure with only a few men on guard outside. Even if your sentries outside give warnings, how can you get out, or fight properly? The worst day of your life will be the one you spend in a house with an enemy tank firing shells through the windows.

Learn to improvise. Every field manual gives solutions to situations in which a full complement of weapons and men is available. But after only a few days of fighting, key personnel will be dead or wounded, and you can’t conceal an advance behind chemical smoke when you’ve used all your smoke. It’s wonderful to rush into a house or a room after tossing in a grenade— if you have one left. When key men on a football team are injured, the second- and third-stringers can fill the gaps. But in a combat unit a missing member or piece of equipment may not be replaced for weeks, if at all.

When advancing, fire your weapon in the enemy’s direction, even if you don’t have a specific target. There are very few targets on the battlefield, but by keeping bullets or missiles cracking over the enemy’s head, you can keep him down in his hole. Although this is the essence of fire superiority, some men go through a campaign and never fire their rifles. Individual riflemen must be taught to fire up a storm if the entire unit is to be aggressive and win. (It has been shown that crew-served weapons are fired more regularly than individual weapons. The idea of “fire teams” should be expanded.)

Always brief your men, showing them the objectives to be taken and letting them scan the immediate terrain, if possible. Too often in combat, men are given orders — “dig in here” or “saddle up, we’re moving out”— without knowing the big picture. This can create a certain lethargy and sometimes chaos, especially at night. Uninformed soldiers, if separated from their unit or forced to take command because of casualties, cannot be fully effective.

Upon receiving my battlefield commission, I made it a point to gather all the men around my map a small group at a time and show them our objectives, an overall picture of the area, and what the high command was trying to accomplish. When they learned that our small objective (possibly a village sitting astride an intersection of two roads) was vital to the success of the entire campaign, the men became more enthusiastic. Even some veteran sergeants who had fought from Africa to the Rhine said this was the first time they had been told what was going on.

When clearing a town of the enemy, stay out of the streets as much as possible. Go over back walls (very quickly), go through courtyards, even punch holes through walls if necessary, and use the rooftops. This is especially important in European-type villages where houses usually have common walls like row houses and are built flush to the street. Remember that frightened natives will lock their doors, so don’t dash across a street expecting to throw open a door to escape from an enemy firing down the street. Vainly trying to break through a heavy locked door creates a firing squad atmosphere.

Practice these tips in training. Regardless of how many months of realistic combat training a man goes through, in the back of his mind he knows that there is a safety officer present, that explosives are set off in safety patterns, and that overhead fire is carefully monitored. This often breeds a certain nonchalance, or even bravado in training.

All of our lives, in fact, we are protected by warning labels, stop signs, barriers to keep us from falling into construction holes, and cautious mothers. Then when a man goes into combat and that first shell or bullet clips by, he suddenly realizes, “My God, they’re trying to kill me!” Such a realization will age you very quickly — and when your first friend is killed or maimed you will suddenly age another ten years.

Regardless of how well you prepare yourself and your soldiers through training, few men are ready for this shock. The realism of the National Training Center at Fort Irwin is a help, but even there a soldier does not see disjointed bodies and screaming comrades.

Every individual soldier, and certainly every commander, must imagine how he will react; he must be prepared to continue functioning, coolly and efficiently, despite the mayhem, blood, and death around him. Calling for medics or wringing your hands does not win battles, but the ability to steel yourself and continue your mission will mold victories.

Learn to think like a hunter or an Indian scout, and survive!

_________________________________

David J. Daze is a retired infantry lieutenant, having received a battlefield commission in France in World War II. He served as a replacement rifleman, as a squad and platoon leader, and as an acting company commander, all in Company L, 30th Infantry, 3d Infantry Division.

5